Mercury was appropriately named after the Roman messenger of the Gods. This is owed to the fact that its apparent motion in the night sky was faster than that of any of the other planets. As astronomers learned more about this “messenger planet”, they came to understand that its motion was due to its close orbit to the Sun, which causes it to complete a single orbit every 88 days.

Mercury’s proximity to the Sun is merely one of its defining characteristics. Compared to the other planets of the Solar System, it experiences severe temperature variations, going from very hot to very cold. It’s also very rocky, and has no atmosphere to speak of. But to truly get a sense of how Mercury stacks up compared to the other planets of the Solar System, we need to a look at how Mercury compares to Earth.

Size, Mass and Orbit:

The diameter of Mercury is 4,879 km, which is approximately 38% the diameter of Earth. In other words, if you put three Mercurys side by side, they would be a little larger than the Earth from end to end. While this makes Mercury smaller than the largest natural satellites in our system – such as Ganymede and Titan – it is more massive and far more dense than they are.

In fact, Mercury’s mass is approximately 3.3 x 1023 kg (5.5% the mass of Earth) which means that its density – at 5.427 g/cm3 – is the second highest of any planet in the Solar System, only slightly less than Earth’s (5.515 g/cm3). This also means that Mercury’s surface gravity is 3.7 m/s2, which is the equivalent of 38% of Earth’s gravity (0.38 g). This means that if you weighed 100 kg (220 lbs) on Earth, you would weigh 38 kg (84 lbs) on Mercury.

Meanwhile, the surface area of Mercury is 75 million square kilometers, which is approximately 10% the surface area of Earth. If you could unwrap Mercury, it would be almost twice the area of Asia (44 million square km). And the volume of Mercury is 6.1 x 1010 km3, which works out to 5.4% the volume of Earth. In other words, you could fit Mercury inside Earth 18 times over and still have a bit of room to spare.

In terms of orbit, Mercury and Earth probably could not be more different. For one, Mercury has the most eccentric orbit of any planet in the Solar System (0.205), compared to Earth’s 0.0167. Because of this, its distance from the Sun varies between 46 million km (29 million mi) at its closest (perihelion) to 70 million km (43 million mi) at its farthest (aphelion).

This puts Mercury much closer to the Sun than Earth, which orbits at an average distance of 149,598,023 km (92,955,902 mi), or 1 AU. This distance ranges from 147,095,000 km (91,401,000 mi) to 152,100,000 km (94,500,000 mi) – 0.98 to 1.017 AU. And with an average orbital velocity of 47.362 km/s (29.429 mi/s), it takes Mercury a total 87.969 Earth days to complete a single orbit – compared to Earth’s 365.25 days.

However, since Mercury also takes 58.646 days to complete a single rotation, it takes 176 Earth days for the Sun to return to the same place in the sky (aka. a solar day). So on Mercury, a single day is twice as long as a single year. Meanwhile on Earth, a single solar day is 24 hours long, owing to its rapid rotation of 1674.4 km/h. Mercury also has the lowest axial tilt of any planet in the Solar System – approximately 0.027°, compared to Earth’s 23.439°.

Structure and Composition:

Much like Earth, Mercury is a terrestrial planet, which means it is composed of silicate minerals and metals that are differentiated between a solid metal core and a silicate crust and mantle. For Mercury, the breakdown of these elements is higher than Earth. Whereas Earth is primarily composed of silicate minerals, Mercury is composed of 70% metallic and 30% of silicate materials.

Also like Earth, Mercury’s interior is believed to be composed of a molten iron that is surrounded by a mantle of silicate material. Mercury’s core, mantle and crust measure 1,800 km, 600 km, and 100-300 km thick, respectively; while Earth’s core, mantle and crust measure 3478 km, 2800 km, and up to 100 km thick, respectively.

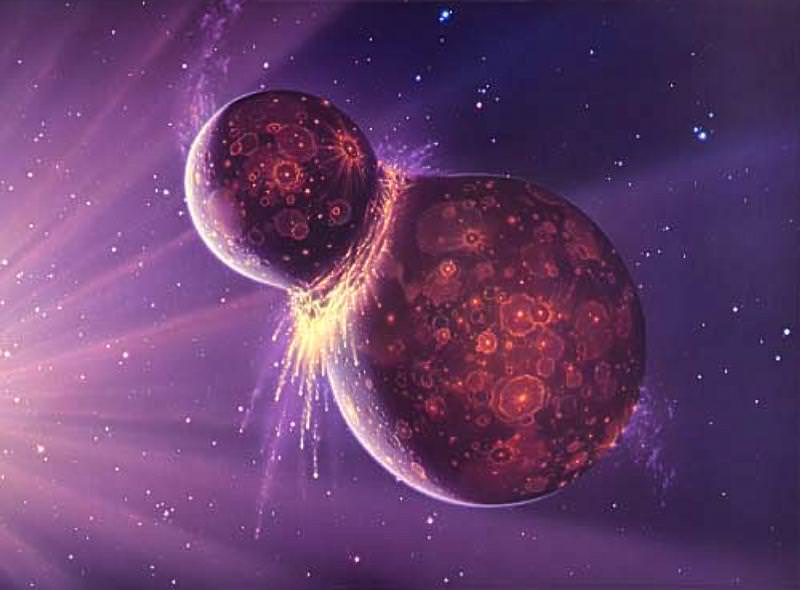

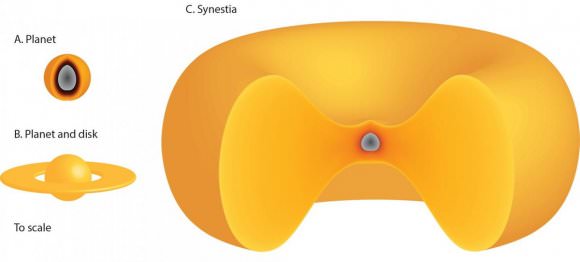

What’s more, geologists estimate that Mercury’s core occupies about 42% of its volume (compared to Earth’s 17%) and the core has a higher iron content than that of any other major planet in the Solar System. Several theories have been proposed to explain this, the most widely accepted being that Mercury was once a larger planet that was struck by a planetesimal that stripped away much of the original crust and mantle.

Surface Features:

In terms of its surface, Mercury is much more like the Moon than Earth. It has a dry landscape pockmarked by asteroid impact craters and ancient lava flows. Combined with extensive plains, these indicate that the planet has been geologically inactive for billions of years.

Names for these features come from a variety of sources. Craters are named for artists, musicians, painters, and authors; ridges are named for scientists; depressions are named after works of architecture; mountains are named for the word “hot” in different languages; planes are named for Mercury in various languages; escarpments are named for ships of scientific expeditions, and valleys are named after radio telescope facilities.

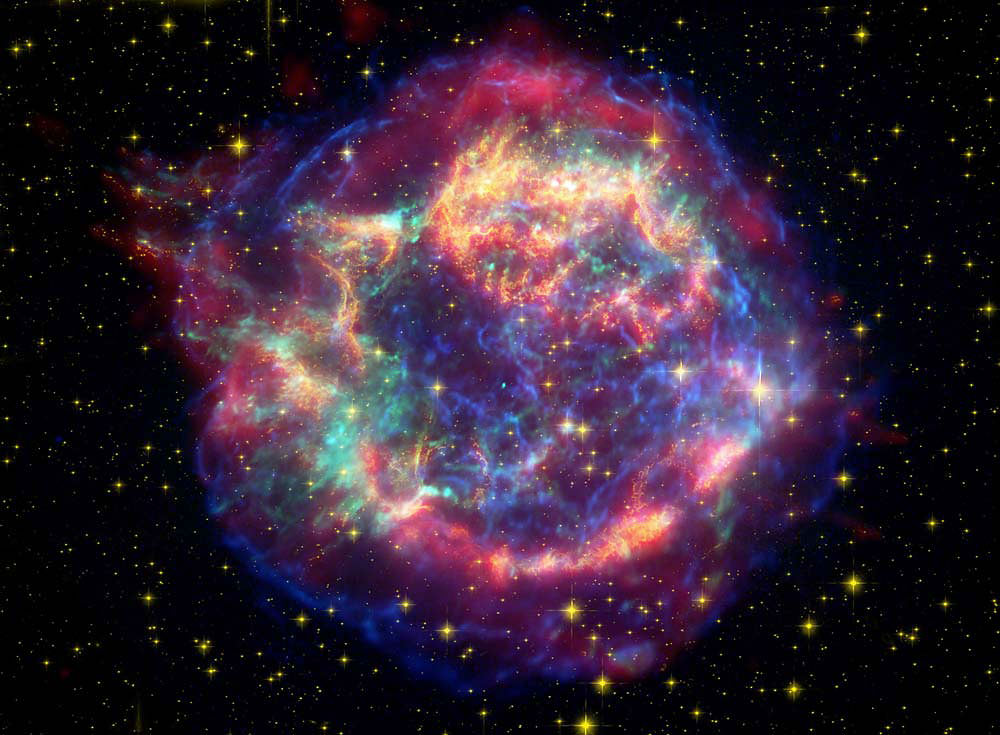

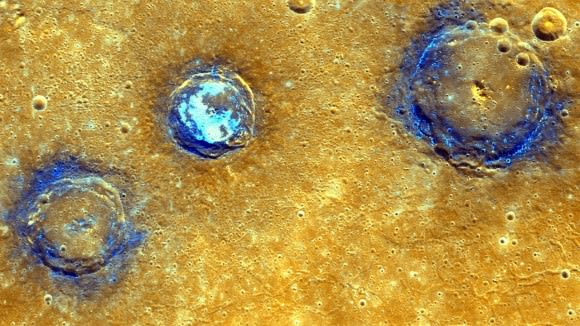

During and following its formation 4.6 billion years ago, Mercury was heavily bombarded by comets and asteroids, and perhaps again during the Late Heavy Bombardment period. Due to its lack of an atmosphere and precipitation, these craters remain intact billions of years later. Craters on Mercury range in diameter from small bowl-shaped cavities to multi-ringed impact basins hundreds of kilometers across.

The largest known crater is Caloris Basin, which measures 1,550 km (963 mi) in diameter. The impact that created it was so powerful that it caused lava eruptions on the other side of the planet and left a concentric ring over 2 km (1.24 mi) tall surrounding the impact crater. Overall, about 15 impact basins have been identified on those parts of Mercury that have been surveyed.

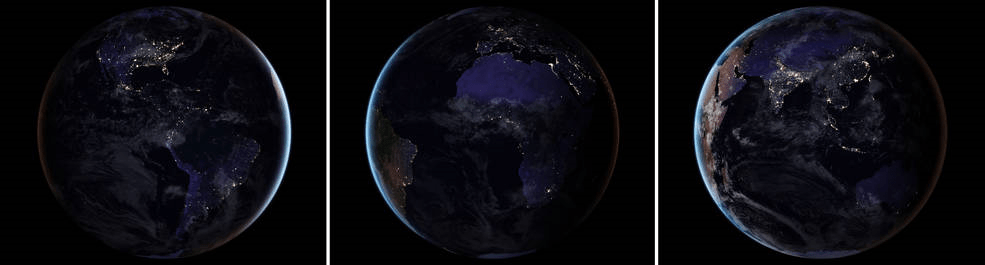

Earth’s surface, meanwhile, is significantly different. For starters, 70% of the surface is covered in oceans while the areas where the Earth’s crust rises above sea level forms the continents. Both above and below sea level, there are mountainous features, volcanoes, scarps (trenches), canyons, plateaus, and abyssal plains. The remaining portions of the surface are covered by mountains, deserts, plains, plateaus, and other landforms.

Mercury’s surface shows many signs of being geologically active in the past, mainly in the form of narrow ridges that extend up to hundreds of kilometers in length. It is believed that these were formed as Mercury’s core and mantle cooled and contracted at a time when the crust had already solidified. However, geological activity ceased billions of years ago and its crust has been solid ever since.

Meanwhile, Earth is still geologically active, owning to convection of the mantle. The lithosphere (the crust and upper layer of the mantle) is broken into pieces called tectonic plates. These plates move in relation to one another and interactions between them is what causes earthquakes, volcanic activity (such as the “Pacific Ring of Fire“), mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation.

Atmosphere and Temperature:

When it comes to their atmospheres, Earth and Mercury could not be more different. Earth has a dense atmosphere composed of five main layers – the Troposphere, the Stratosphere, the Mesosphere, the Thermosphere, and the Exosphere. Earth’s atmosphere is also primarily composed of nitrogen (78%) and oxygen (21%) with trace concentrations of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and other gaseous molecules.

Because of this, the average surface temperature on Earth is approximately 14°C, with plenty of variation due to geographical region, elevation, and time of year. The hottest temperature ever recorded on Earth was 70.7°C (159°F) in the Lut Desert of Iran, while the coldest temperature was -89.2°C (-129°F) at the Soviet Vostok Station on the Antarctic Plateau.

Mercury, meanwhile, has a tenuous and variable exosphere that is made up of hydrogen, helium, oxygen, sodium, calcium, potassium and water vapor, with a combined pressure level of about 10-14 bar (one-quadrillionth of Earth’s atmospheric pressure). It is believed this exosphere was formed from particles captured from the Sun, volcanic outgassing and debris kicked into orbit by micrometeorite impacts.

Because it lacks a viable atmosphere, Mercury has no way to retain the heat from the Sun. As a result of this and its high eccentricity, the planet experiences far more extreme variations in temperature than Earth does. Whereas the side that faces the Sun can reach temperatures of up to 700 K (427° C), the side that is in darkness can reach temperatures as low as 100 K (-173° C).

Despite these highs in temperature, the existence of water ice and even organic molecules has been confirmed on Mercury’s surface. The floors of deep craters at the poles are never exposed to direct sunlight, and temperatures there remain below the planetary average. In this respect, Mercury and Earth have something else in common, which is the presence of water ice in its polar regions.

Magnetic Fields:

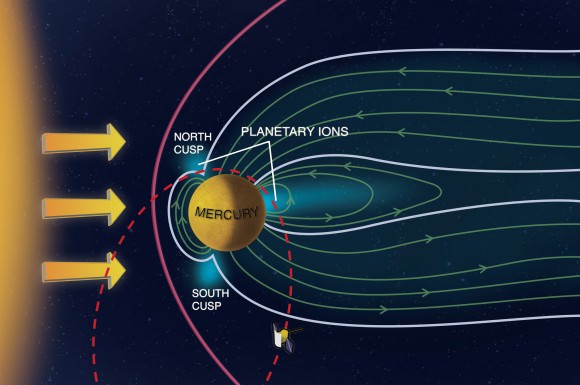

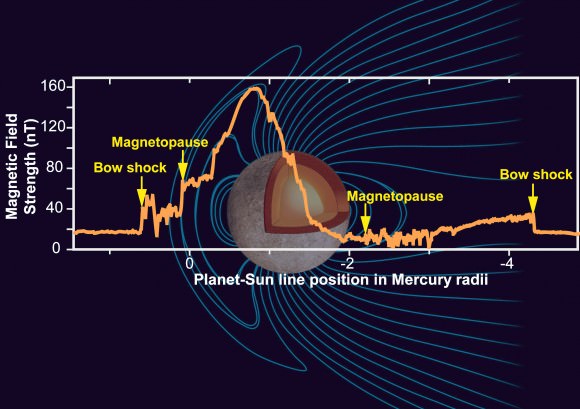

Much like Earth, Mercury has a significant, and apparently global, magnetic field, one which is about 1.1% the strength of Earth’s. It is likely that this magnetic field is generated by a dynamo effect, in a manner similar to the magnetic field of Earth. This dynamo effect would result from the circulation of the planet’s iron-rich liquid core.

Mercury’s magnetic field is strong enough to deflect the solar wind around the planet, thus creating a magnetosphere. The planet’s magnetosphere, though small enough to fit within Earth, is strong enough to trap solar wind plasma, which contributes to the space weathering of the planet’s surface.

All told, Mercury and Earth are in stark contrast. While both are terrestrial in nature, Mercury is significantly smaller and less massive than Earth, though it has a similar density. Mercury’s composition is also much more metallic than that of Earth, and its 3:2 orbital resonance results in a single day being twice as long as a year.

But perhaps most stark of all are the extremes in temperature variations that Mercury goes through compared to Earth. Naturally, this is due to the fact that Mercury orbits much closer to the Sun than the Earth does and has no atmosphere to speak of. And its long days and long nights also mean that one side is constantly being baked by the Sun, or in freezing darkness.

We have written many stories about Mercury on Universe Today. Here’s Interesting Facts About Mercury, What Type of Planet is Mercury?, How Long is a Day on Mercury?, The Orbit of Mercury. How Long is a Year on Mercury?, What is the Surface Temperature of Mercury?, Water Ice and Organics Found at Mercury’s North Pole, Characteristics of Mercury,, Surface of Mercury, and Missions to Mercury

If you’d like more information on Mercury, check out NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide, and here’s a link to NASA’s MESSENGER Misson Page.

We have also recorded a whole episode of Astronomy Cast that’s just about planet Mercury. Listen to it here, Episode 49: Mercury.

Sources: