Thunder and lightning. When it comes to the forces of nature, few other things have inspired as much fear, reverence, or fascination – not to mention legends, mythos, and religious representations. As with all things in the natural world, what was originally seen as a act by the Gods (or other supernatural causes) has since come to be recognized as a natural phenomena.

But despite all that human beings have learned over the centuries, a degree of mystery remains when it comes to lightning. Experiments have been conducted since the time of Benjamin Franklin; however, we are still heavily reliant on theories as to how lighting behaves.

Description:

By definition, lightning is a sudden electrostatic discharge during an electrical storm. This discharge allows charged regions in the atmosphere to temporarily equalize themselves, when they strike an object on the ground. Although lightning is always accompanied by the sound of thunder, distant lightning may be seen but be too far away for the thunder to be heard.

Types:

Lightning can take one of three forms, which are defined by what is at the “end” of the branch channel (i.e. lightning bolt). For example, there is intra-cloud lighting (IC), which takes place between electrically charged regions of a cloud; cloud-to-cloud (CC) lighting, where it occurs between one functional thundercloud and another; and cloud-to-ground (CG) lightning, which primarily originates in the thundercloud and terminates on an Earth surface (but may also occur in the reverse direction).

Intra-cloud lightning most commonly occurs between the upper (or “anvil”) portion and lower reaches of a given thunderstorm. In such instances, the observer may see only a flash of light without hearing any thunder. The term “heat-lightning” is often applied here, due to the association between locally experienced warmth and the distant lightning flashes.

In the case of cloud-to-cloud lightning, the charge typically originates from beneath or within the anvil and scrambles through the upper cloud layers of a thunderstorm, normally generating a lightning bolt with multiple branches.

Cloud-to-ground (CG) is the best known type of lightning, though it is the third-most common – accounting for approximately 25% cases worldwide. In this case, the lightning takes the form of a discharge between a thundercloud and the ground, and is usually negative in polarity and initiated by a stepped branch moving down from the cloud.

CG lightning is the best known because, unlike other forms of lightning, it terminates on a physical object (most often the Earth), and therefore lends itself to being measured by instruments. In addition, it poses the greatest threat to life and property, so understanding its behavior is seen as a necessity.

Properties:

Lighting originates when wind updrafts and downdrafts take place in the atmosphere, creating a charging mechanism that separates electric charges in clouds – leaving negative charges at the bottom and positive charges at the top. As the charge at the bottom of the cloud keeps growing, the potential difference between cloud and ground, which is positively charged, grows as well.

When a breakdown at the bottom of the cloud creates a pocket of positive charge, an electrostatic discharge channel forms and begins traveling downwards in steps tens of meters in length. In the case of IC or CC lightning, this channel is then drawn to other pockets of positive charges regions. In the case of CG strikes, the stepped leader is attracted to the positively charged ground.

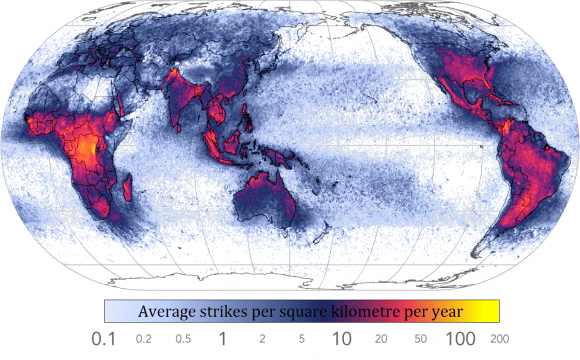

Many factors affect the frequency, distribution, strength and physical properties of a “typical” lightning flash in a particular region of the world. These include ground elevation, latitude, prevailing wind currents, relative humidity, proximity to warm and cold bodies of water, etc. To a certain degree, the ratio between IC, CC and CG lightning may also vary by season in middle latitudes.

About 70% of lightning occurs over land in the tropics where atmospheric convection is the greatest. This occurs from both the mixture of warmer and colder air masses, as well as differences in moisture concentrations, and it generally happens at the boundaries between them. In the tropics, where the freezing level is generally higher in the atmosphere, only 10% of lightning flashes are CG. At the latitude of Norway (around 60° North latitude), where the freezing elevation is lower, 50% of lightning is CG.

Effects:

In general, lightning has three measurable effects on the surrounding environment. First, there is the direct effect of a lightning strike itself, in which structural damage or even physical harm can result. When lighting strikes a tree, it vaporizes sap, which can result in the trunk exploding or a large branches snapping off and falling to the ground.

When lightning strikes sand, soil surrounding the plasma channel may melt, forming tubular structures called fulgurites. Buildings or tall structures hit by lightning may be damaged as the lightning seeks unintended paths to ground. And though roughly 90% of people struck by lightning survive, humans or animals struck by lightning may suffer severe injury due to internal organ and nervous system damage.

Thunder is also a direct result of electrostatic discharge. Because the plasma channel superheats the air in its immediate vicinity, the gaseous molecules undergo a rapid increase in pressure and thus expand outward from the lightning creating an audible shock wave (aka. thunder). Since the sound waves propagate not from a single source, but along the length of the lightning’s path, the origin’s varying distances can generate a rolling or rumbling effect.

High-energy radiation also results from a lightning strike. These include x-rays and gamma rays, which have been confirmed through observations using electric field and X-ray detectors, and space-based telescopes.

Studies:

The first systematic and scientific study of lightning was performed by Benjamin Franklin during the second half of the 18th century. Prior to this, scientists had discerned how electricity could be separated into positive and negative charges and stored. They had also noted a connection between sparks produced in a laboratory and lightning.

Franklin theorized that clouds are electrically charged, from which it followed that lightning itself was electrical. Initially, he proposed testing this theory by placing iron rod next to a grounded wire, which would be held in place nearby by an insulated wax candle. If the clouds were electrically charged as he expected, then sparks would jump between the iron rod and the grounded wire.

In 1750, he published a proposal whereby a kite would be flown in a storm to attract lightning. In 1752, Thomas Francois D’Alibard successfully conducted the experiment in France, but used a 12 meter (40 foot) iron rod instead of a kite to generate sparks. By the summer of 1752, Franklin is believed to have conducted the experiment himself during a large storm that descended on Philadelphia.

For his upgraded version of the experiment, Franking attacked a key to the kite, which was connected via a damp string to an insulating silk ribbon wrapped around the knuckles of Franklin’s hand. Franklin’s body, meanwhile, provided the conducting path for the electrical currents to the ground. In addition to showing that thunderstorms contain electricity, Franklin was able to infer that the lower part of the thunderstorm was generally negatively charged as well.

Little significant progress was made in understanding the properties of lightning until the late 19th century when photography and spectroscopic tools became available for lightning research. Time-resolved photography was used by many scientists during this period to identify individual lightning strokes that make up a lightning discharge to the ground.

Lightning research in modern times dates from the work of C.T.R. Wilson (1869 – 1959) who was the first to use electric field measurements to estimate the structure of thunderstorm charges involved in lightning discharges. Wilson also won the Nobel Prize for the invention of the Cloud Chamber, a particle detector used to discern the presence of ionized radiation.

By the 1960’s, interest grew thanks to the intense competition brought on by the Space Age. With spacecraft and satellites being sent into orbit, there were fears that lightning could post a threat to aerospace vehicles and the solid state electronics used in their computers and instrumentation. In addition, improved measurement and observational capabilities were made possible thanks to improvements in space-based technologies.

In addition to ground-based lightning detection, several instruments aboard satellites have been constructed to observe lightning distribution. These include the Optical Transient Detector (OTD), aboard the OrbView-1 satellite launched on April 3rd, 1995, and the subsequent Lightning Imaging Sensor (LIS) aboard TRMM, which was launched on November 28th, 1997.

Volcanic Lightning:

Volcanic activity can produce lightning-friendly conditions in multiple ways. For instance, the powerful ejection of enormous amounts of material and gases into the atmosphere creates a dense plume of highly charged particles, which establishes the perfect conditions for lightning. In addition, the ash density and constant motion within the plume continually produces electrostatic ionization. This in turn results in frequent and powerful flashes as the plume tries to neutralize itself.

This type of thunderstorm is often referred to as a “dirty thunderstorm” due to the high solid material (ash) content. There have been several recorded instances of volcanic lightning taking place throughout history. For example, during the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE, Pliny the Younger noted several powerful and frequent flashes taking place around the volcanic plume.

Extraterrestrial Lightning:

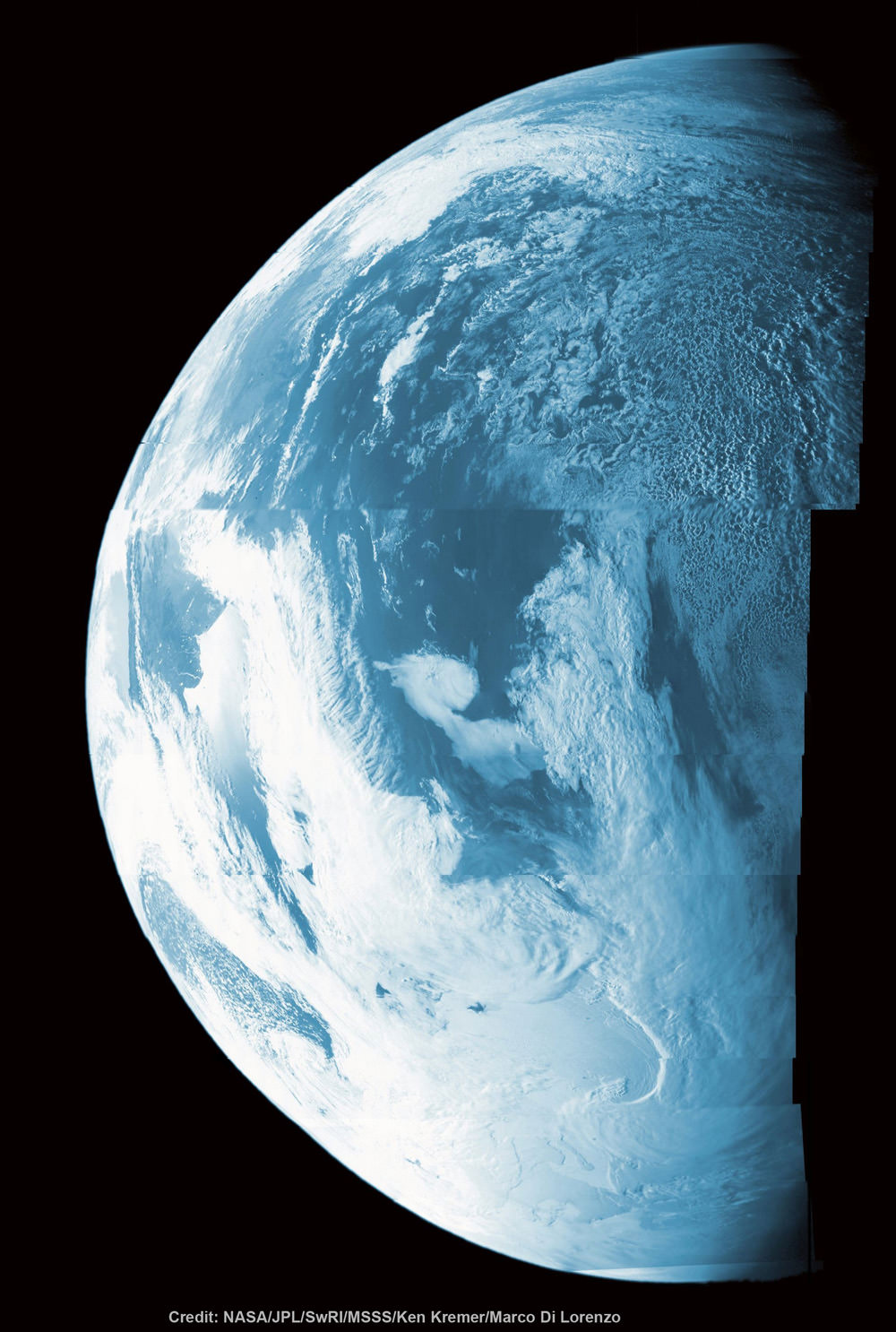

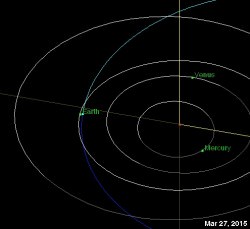

Lightning has been observed within the atmospheres of other planets in our Solar System, such as Venus, Jupiter and Saturn. In the case of Venus, the first indications that lightning may be present in the upper atmosphere were observed by the Soviet Venera and U.S. Pioneer missions in the 1970s and 1980s. Radio pulses recorded by the Venus Express spacecraft (in April 2006) were confirmed as originating from lightning on Venus.

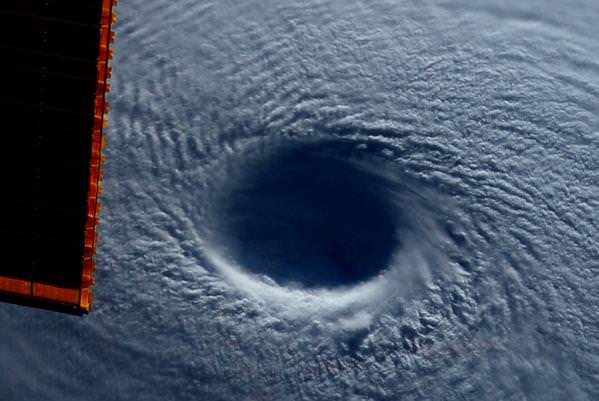

Thunderstoms that are similar to those on Earth have been observed on Jupiter. They are believed to be the result of moist convection with Jupiter’s troposphere, where convective plumes bring wet air up from the depths to the upper parts of the atmosphere, where it then condenses into clouds of about 1000 km in size.

The imaging of the night-side hemisphere of Jupiter by the Galileo in the 1990 and by the Cassini spacecraft in December of 2000 revealed that storms are always associated with lightning on Jupiter. While lighting strikes are on average a few times more powerful than those on Earth, they are apparently less frequent. A few flashes have been detected in polar regions, making Jupiter the second known planet after Earth to exhibit polar lightning.

Lighting has also been observed on Saturn. The first instance occurred in 2010 when the Cassini space probe detected flashes on the night-side of the planet, which happened to coincide with the detection of powerful electrostatic discharges. In 2012, images taken by the Cassini probe in 2011 showed how the massive storm that wrapped the northern hemisphere was also generating powerful flashes of lightning.

Once thought to be the “hammer of the Gods”, lightning has since come to be understood as a natural phenomena, and one that exists on other terrestrial worlds and even gas giants. As we come to learn more about how lighting behaves here on Earth, that knowledge could go a long way in helping us to understand weather systems on other worlds as well.

We have written many articles about lightning here at Universe Today. Here’s an article about NASA’s biggest lightning protection system. And here’s an interesting article about the possible connection between solar wind and lightning.

If you’d like more info on lightning, check out the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Homepage. And here’s a link to NASA’s Earth Observatory.

We also have an episode of Astronomy Cast, titled Episode 51: Earth.