The Whitewater-Baldy fire is the largest wildfire in New Mexico’s history and has charred more than 465 square miles of the Gila National Forest since it started back on May 16, 2012 after several lightning strikes in the area. This wildfire produced so much smoke that it was visible even at night to the astronaut photographers on the International Space Station. This image was taken on June 2, 2012 by the crew of Expedition 31 on the ISS, with a Nikon D3S digital camera. A Russian spacecraft docked to the station is visible on the left side of the image.

Credit: NASA Earth Observatory website.

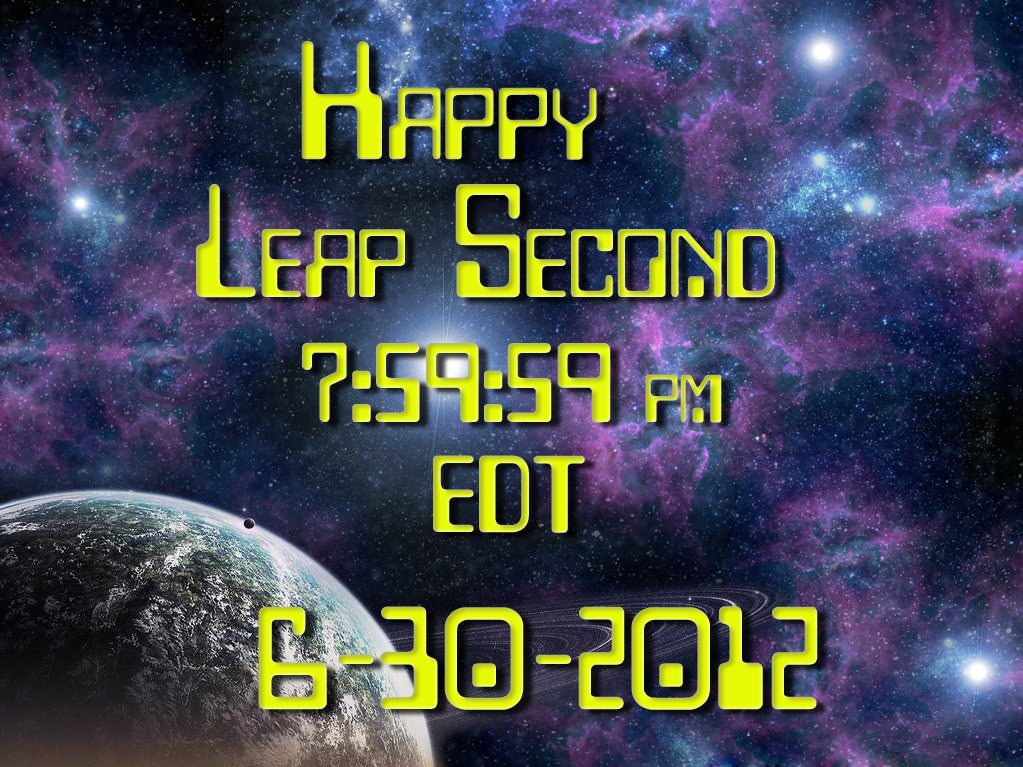

What are You Doing With Your Added Leap Second Today?

Everyone loves a long weekend, this weekend will be officially one second longer than usual. An extra second, or “leap” second, will be added at midnight UTC tonight, June 30, 2012, to account for the fact that it is taking Earth longer and longer to complete one full turn, or one a solar day. Granted, it the additional time is not very long, but the extra second will ensure that the atomic clocks we use to keep time will be in synch with Earth’s rotational period.

“The solar day is gradually getting longer because Earth’s rotation is slowing down ever so slightly,” says Daniel MacMillan of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

So, rather than changing from 23:59:59 on June 30 to 00:00:00 on July 1, the official time will get an extra second at 23:59:60.

About every one and a half years, one extra second is added to Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) and clocks around the world. Since 1972, a total of 24 seconds have been added. This means that the Earth has slowed down 24 seconds compared to atomic time since then.

However, this doesn’t mean that days are 24 seconds longer now, as only the days on which the leap seconds are inserted have 86,401 seconds instead of the usual 86,400 seconds.

This leap second accounts for the fact that the Earth’s rotation around its own axis, which determines the length of a day, slows down over time while the atomic clocks we use to measure time tick away at almost the same speed over millions of years.

NASA explains it this way:

Scientists know exactly how long it takes Earth to rotate because they have been making that measurement for decades using an extremely precise technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI). VLBI measurements are made daily by an international network of stations that team up to conduct observations at the same time and correlate the results. NASA Goddard provides essential coordination of these measurements, as well as processing and archiving the data collected. And NASA is helping to lead the development of the next generation of VLBI system through the agency’s Space Geodesy Project, led by Goddard.

From VLBI, scientists have learned that Earth is not the most reliable timekeeper. The planet’s rotation is slowing down overall because of tidal forces between Earth and the moon. Roughly every 100 years, the day gets about 1.4 milliseconds, or 1.4 thousandths of a second, longer. Granted, that’s about 100 or 200 times faster than the blink of an eye. But if you add up that small discrepancy every day for years and years, it can make a very big difference indeed.

“At the time of the dinosaurs, Earth completed one rotation in about 23 hours,” says MacMillan, who is a member of the VLBI team at NASA Goddard. “In the year 1820, a rotation took exactly 24 hours, or 86,400 standard seconds. Since 1820, the mean solar day has increased by about 2.5 milliseconds.”

By the 1950s, scientists had already realized that some scientific measurements and technologies demanded more precise timekeeping than Earth’s rotation could provide. So, in 1967, they officially changed the definition of a second. No longer was it based on the length of a day but on an extremely predictable measurement made of electromagnetic transitions in atoms of cesium. These “atomic clocks” based on cesium are accurate to one second in 1,400,000 years. Most people around the world rely on the time standard based on the cesium atom: Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).

Another time standard, called Universal Time 1 (UT1), is based on the rotation of Earth on its axis with respect to the sun. UT1 is officially computed from VLBI measurements, which rely on astronomical reference points and have a typical precision of 5 microseconds, or 5 millionths of a second, or better.

“These reference points are very distant astronomical objects called quasars, which are essentially motionless when viewed from Earth because they are located several billion light years away,” says Goddard’s Stephen Merkowitz, the Space Geodesy Project manager.

For VLBI observations, several stations around the world observe a selected quasar at the same time, with each station recording the arrival of the signal from the quasar; this is done for a series of quasars during a typical 24-hour session. These measurements are made with such exquisite accuracy that it’s actually possible to determine that the signal does not arrive at every station at exactly the same time. From the miniscule differences in arrival times, scientists can figure out the positions of the stations and Earth’s orientation in space, as well as calculating Earth’s rotation speed relative to the quasar positions.

Originally, leap seconds were added to provide a UTC time signal that could be used for navigation at sea. This motivation has become obsolete with the development of GPS (Global Positioning System) and other satellite navigation systems. These days, a leap second is inserted in UTC to keep it within 0.9 seconds of UT1.

Normally, the clock would move from 23:59:59 to 00:00:00 the next day. Instead, at 23:59:59 on June 30, UTC will move to 23:59:60, and then to 00:00:00 on July 1. In practice, this means that clocks in many systems will be turned off for one second.

Proposals have been made to abolish the leap second and let the two time standards drift apart. This is because of the cost of planning for leap seconds and the potential impact of adjusting or turning important systems on and off in synch. No decision will made about that, however, until 2015 at the earliest by the International Telecommunication Union, a specialized agency of the United Nations that addresses issues in information and communication technologies. If the two standards are allowed to go further and further out of synch, they will differ by about 25 minutes in 500 years.

In the meantime, leap seconds will continue to be added to the official UTC timekeeping. The 2012 leap second is the 35th leap second to be added and the first since 2008.

Lead image credit: Rick Ellis

Sources: NASA, TimeandDate.com

Smoking Wildfires Seen From Space

Wildfires continue to rage across the western United States, burning forests and property alike, and even the most remote have sent up enormous plumes of smoke that are plainly visible to astronauts aboard the Space Station.

The photo above was taken by an Expedition 31 crew member on June 27, showing thick smoke drifting northeast from the Fontenelle fire currently burning in Wyoming. More plumes can be seen to the north.

Utah’s Great Salt Lake can be seen at the bottom right of the image. Its two-tone coloration is due to different species of algae that live in the lake, which is split by the physical barrier of a railroad causeway.

You can watch a video of the wildfires in the west taken from the ISS here, and see more “fire and smoke” news and images from space here.

Image: NASA

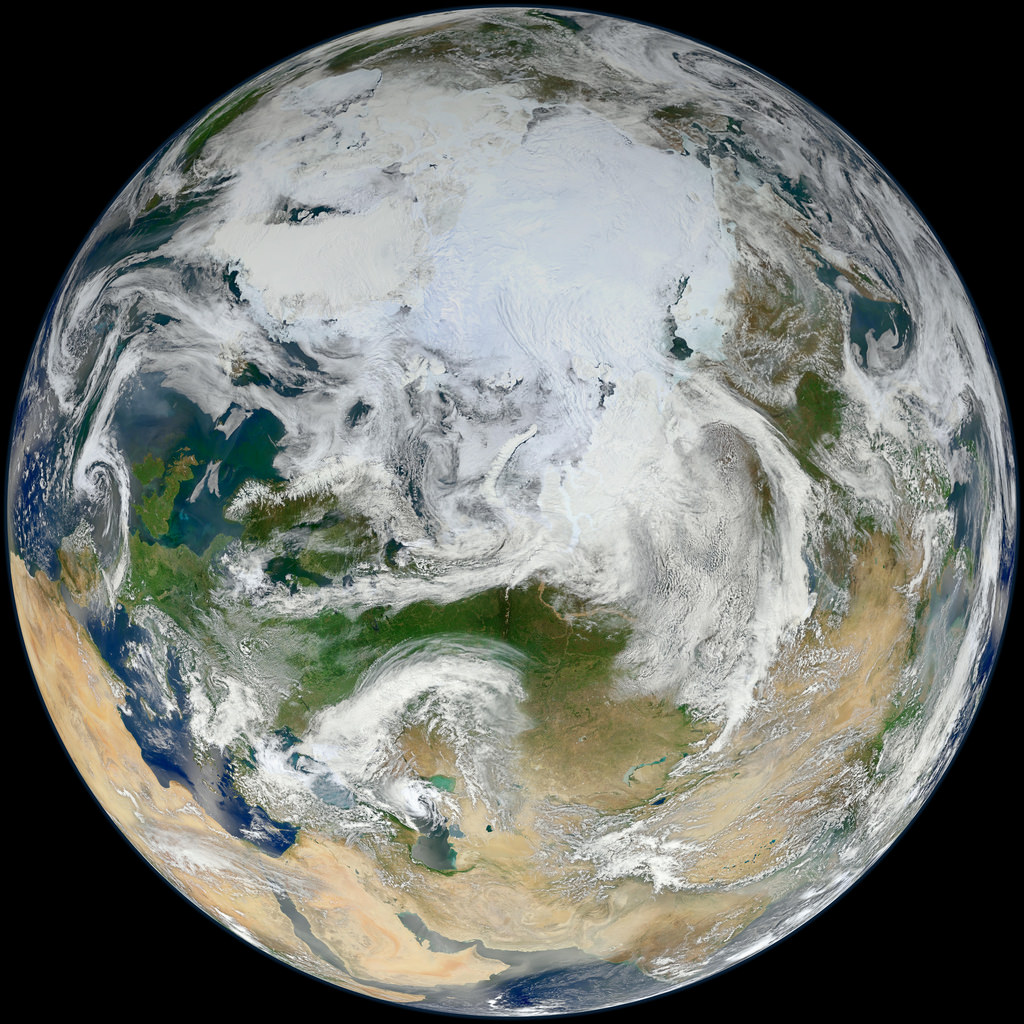

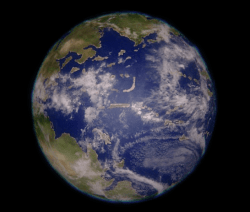

Blue Marble 2012: The Arctic Edition

This latest portrait of Earth from NASA’s Suomi NPP satellite puts the icy Arctic in the center, showing the ice and clouds that cover our planet’s northern pole. The image you see here was created from data acquired during fifteen orbits of Earth.

In January of this year Suomi NPP images of Earth were used to create an amazing “Blue Marble” image that spread like wildfire across the internet, becoming one of the latest “definitive” images of our planet. Subsequent images have been released by the team at Goddard Space Flight Center, each revealing a different perspective of Earth.

See a full-sized version of the image above here.

NASA launched the National Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System Preparatory Project (or NPP) on October 28, 2011 from Vandenberg Air Force Base. On Jan. 24, NPP was renamed Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership, or Suomi NPP, in honor of the late Verner E. Suomi. It’s the first satellite designed to collect data to improve short-term weather forecasts and increase understanding of long-term climate change.

Suomi NPP orbits the Earth about 14 times each day and observes nearly the entire surface of the planet.

Image credit: NASA/GSFC/Suomi NPP

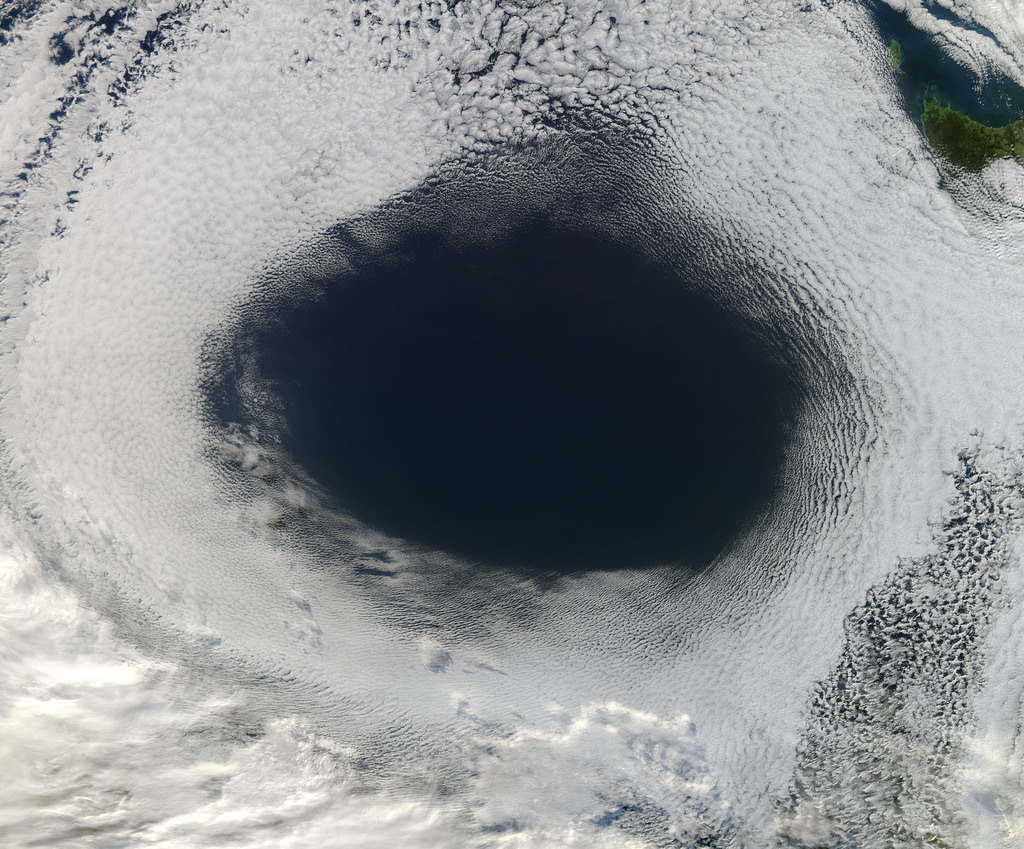

There’s a Hole in the Sky!

[/caption]

Well, not the sky exactly, but definitely in the clouds!

This image, acquired by NASA’s Aqua satellite on June 5, shows an enormous oval hole in the clouds above the southern Pacific Ocean, approximately 500 miles (800 km) off the southwestern coast of Tasmania. The hole itself is several hundred miles across, and is the result of high pressure air in the upper atmosphere.

According to Rob Gutro of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, “This is a good visible example of how upper-level atmospheric features affect the lower atmosphere, because the cloud hole is right under the center of a strong area of high pressure. High pressure forces air down to the surface blocking cloud formation. In addition, the altocumulus clouds are rotating counter-clockwise around the hole, which in the southern hemisphere indicates high pressure.”

The northwestern tip of Tasmania and King Island can be seen in the upper right of the image.

The Aqua mission is a part of the NASA-centered international Earth Observing System (EOS). Launched on May 4, 2002, Aqua has six Earth-observing instruments on board, collecting a variety of global data sets about the Earth’s water cycle. Read more about Aqua here.

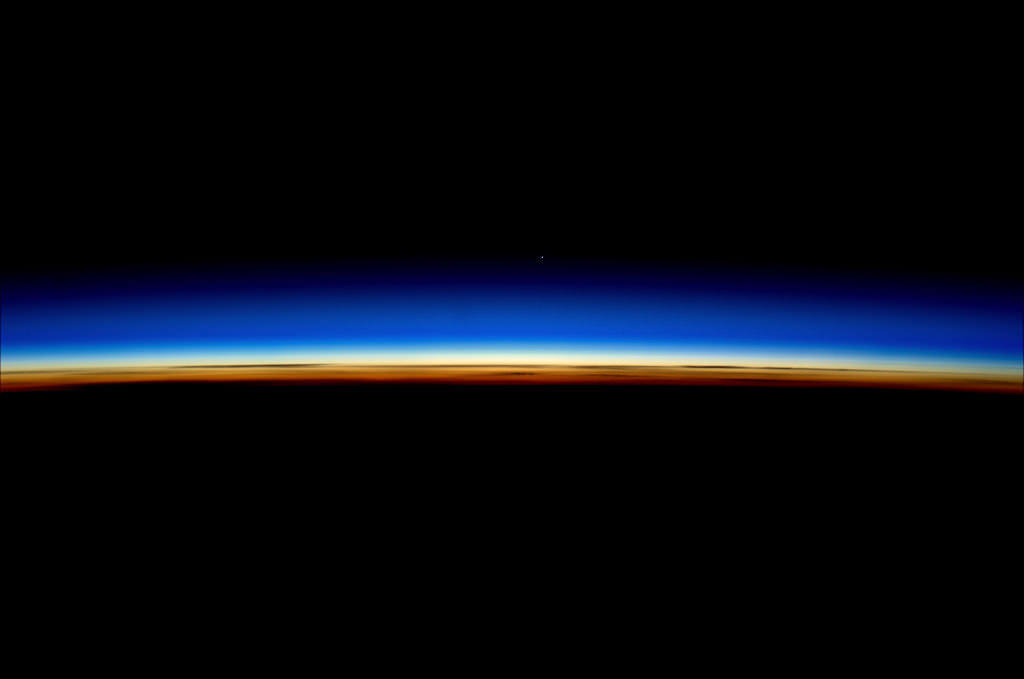

Tomorrow’s Transit Will be the First Photographed From Space

[/caption]

ESA astronaut Andre Kuipers captured this stunning image of Earth’s limb with Venus shining brightly above on the morning of June 4, 2012. While it’s a fantastic shot in its own right, it’s just a warm-up for tomorrow’s big transit event, which will be watched by millions of people all over the world — as well as a select few aboard the ISS!

While many people will be taking advantage of this last opportunity to see Venus pass across the face of the Sun — a relatively rare event that’s only happened six times since the invention of the telescope, and won’t occur again until 2117 — the crew of the International Space Station is preparing to become the first astronaut to photograph it from space!

Expedition 31 flight engineer Don Pettit knew he’d be up in orbit when this transit takes place, and he went prepared.

“I’ve been planning this for a while,” says Pettit. “I knew the Transit of Venus would occur during my rotation, so I brought a solar filter with me when my expedition left for the ISS in December 2011.”

(See more of Don Pettit’s in-orbit photography: Timelapse of a Moonrise Seen From The ISS)

Even though the 2004 transit happened while the ISS was manned, the crew then didn’t have filters through with to safely view it.

Pettit will be shooting the transit through the windows of the cupola. He’ll even be removing a scratch-resistant layer first, in order to get the sharpest, clearest images possible — only the third time that’s ever been done.

Don’s images should be — no pun intended — brilliant.

“I’ll be using a high-end Nikon D2Xs camera and an 800mm lens with a full-aperture white light solar filter,” he says.

And if you want to follow along with the transit as it’s seen from down here on Earth, be sure to tune in to Universe Today’s live broadcast on Tuesday, June 5 at 5 p.m. EDT where Fraser Cain will be hosting a marathon event along with guests Pamela Gay, Phil Plait (a.k.a. the Bad Astronomer) and more as live views are shared from around the world.

Unless you plan on being around in 2117, this will be your last chance to witness a transit of Venus!

Read more about Don Pettit’s photo op on NASA Science News here.

When Everything On Earth Died

[/caption]

Hey, remember that one time when 90% of all life on Earth got wiped out?

I don’t either. But it’s a good thing it happened because otherwise none of us would be here to… not remember it. Still, the end-Permian Extinction — a.k.a. the Great Dying — was very much a real crisis for life on Earth 252 million years ago. It makes the K-T extinction event of the dinosaurs look like a rather nice day by comparison, and is literally the most catastrophic event known to have ever befallen Earthly life. Luckily for us (and pretty much all of the species that have arisen since) the situation eventually sorted itself out. But how long did that take?

The Permian Extinction was a perfect storm of geological events that resulted in the disappearance of over 90% of life on Earth — both on land and in the oceans. (Or ocean, as I should say, since at that time the land mass of Earth had gathered into one enormous continent — called Pangaea — and thus there was one ocean, referred to as Panthalassa.) A combination of increased volcanism, global warming, acid rain, ocean acidification and anoxia, and the loss of shallow sea habitats (due to the single large continent) set up a series of extinctions that nearly wiped our planet’s biological slate clean.

Exactly why the event occurred and how Earth returned to a state in which live could once again thrive is still debated by scientists, but it’s now been estimated that the recovery process took about 10 million years.

(Read: Recovering From a Mass Extinction is Slow Going)

Research by Dr. Zhong-Qiang Chen from the China University of Geosciences in Wuhan, and Professor Michael Benton from the University of Bristol, UK, show that repeated setbacks in conditions on Earth continued for 5 to 6 million years after the initial wave of extinctions. It appears that every time life would begin to recover within an ecological niche, another wave of environmental calamities would break.

“Life seemed to be getting back to normal when another crisis hit and set it back again,” said Prof. Benton. “The carbon crises were repeated many times, and then finally conditions became normal again after five million years or so.”

“The causes of the killing – global warming, acid rain, ocean acidification – sound eerily familiar to us today. Perhaps we can learn something from these ancient events.”

– Michael Benton, Professor of Vertebrate Palaeontology at the University of Bristol

It wasn’t until the severity of the crises abated that life could gradually begin reclaiming and rebuilding Earth’s ecosystems. New forms of life appeared, taking advantage of open niches to grab a foothold in a new world. It was then that many of the ecosystems we see today made their start, and opened the door for the rise of Earth’s most famous prehistoric critters: the dinosaurs.

“The event had re-set evolution,” said Benton. “However, the causes of the killing – global warming, acid rain, ocean acidification – sound eerily familiar to us today. Perhaps we can learn something from these ancient events.”

The team’s research was published in the May 27 issue of Nature Geoscience. Read more on the University of Bristol’s website here.

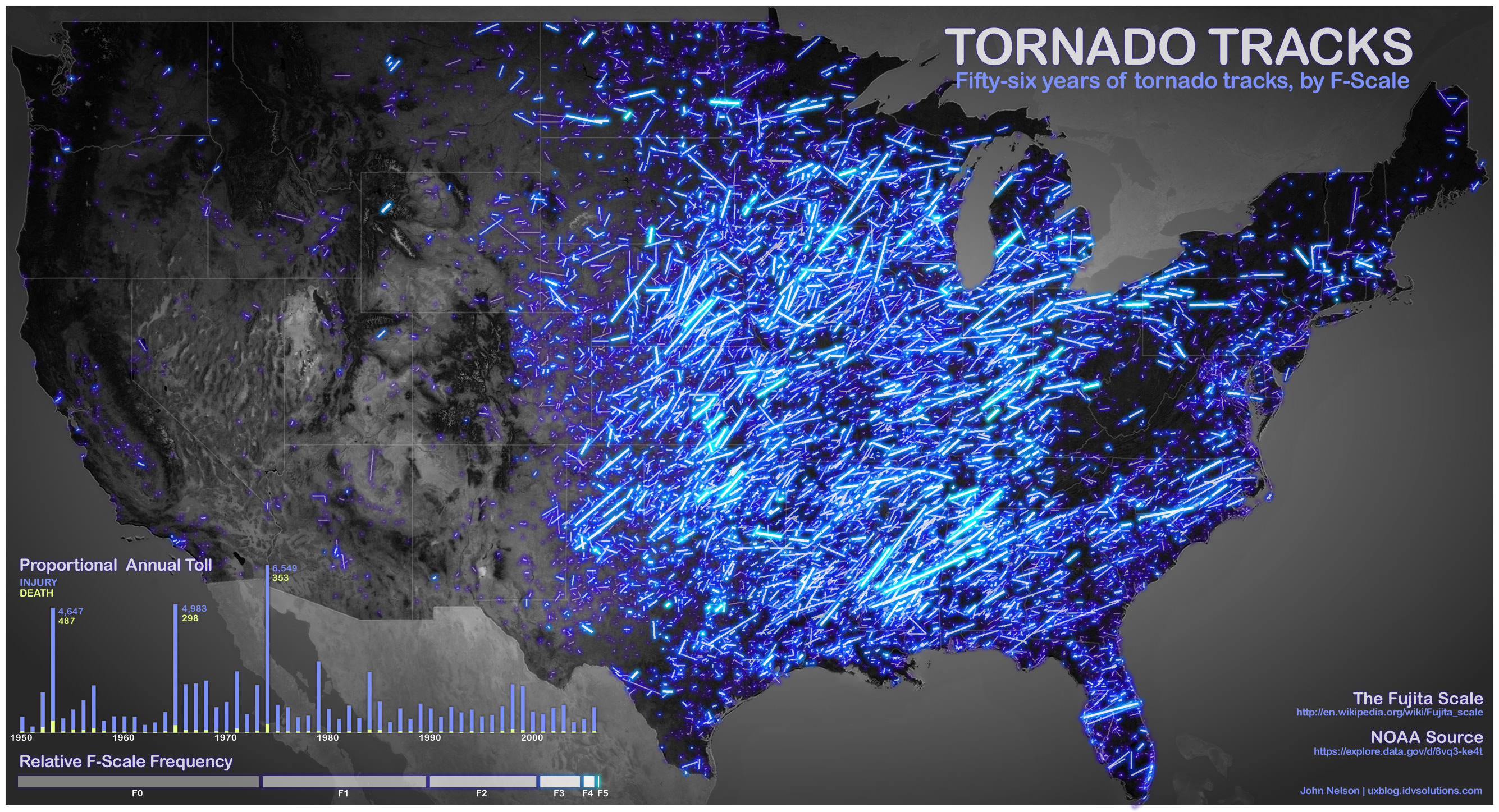

Stunning Visualization of 56 Years of Tornadoes in the US

[/caption]

It’s a wonder of nature, baby. Using information from data.gov, tech blogger John Nelson has created this spectacular image of tornado paths in the US over a 56 year period. The graphic categorizes the storms by F-scale with the brighter neon lines representing more violent storms.

Makes you want to hang on to something solid.

Nelson also provided some stats on all the storms in the different categories:

The numbers represent total deaths, total injuries, average miles the storms traveled

F0: 7, 267, 2

F1: 111, 3270, 6.58

F2: 363, 10373, 11.4

F3: 958, 18160, 17.80

F4: 1912, 28427, 28.62

F5: 1013, 11038, 38.87

This provides a new appreciation for the term “suck zone” used in the movie “Twister.”

While tornadoes don’t travel in straight lines, Nelson explains that based on the data, the vectors were created using touchdown points and liftoff points.

Nelson said he got the data from this Data.gov page doing a “tornado tracks” search.

Fly To Space For $320!

[/caption]

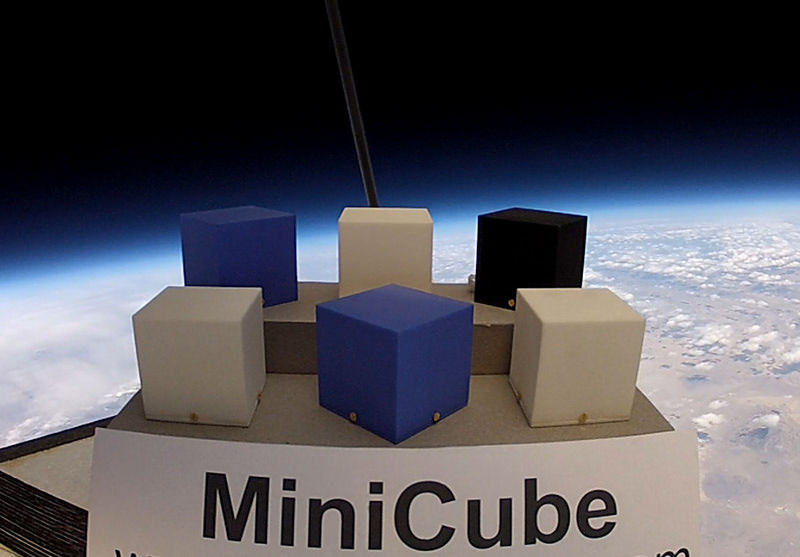

Ok, at 100,000 feet it’s not really “space” but for $320 USD JP Aerospace is offering a very affordable way to get your research experiment, brand statement, artwork or anything you can imagine (and that fits into a 50mm cube, weight limits apply) into the upper atmosphere. Pretty cool!

Touting its program as “stomping down the cost of space”, Rancho Cordova, California-based JP Aerospace (America’s OTHER Space Program) is offering its MiniCube platform to anyone who wants to get… well, something… carried up to 100,000 feet.

The plastic MiniCubes are each 1mm-thick, 48mm wide and 50mm high. Their bases have a standard tripod mount, and the MiniCubes can be cut, drilled, printed and/or modified within parameters before being mailed back to JPA for flight. Once the MiniCubes are flown, they are returned to their customers along with a data sheet and a CD of images from the mission. All for $320!

Again, it may not technically be “space”, but the view’s not bad.

At the time of this writing there are 20 spaces available for the next JPA high-altitude balloon flight on September 22.

Find out more about JPA, MiniCubes, size specifications and how to purchase a space on the next flight here.

All images via JPAerospace.com

A New Look at Apollo Samples Supports Ancient Impact Theory

[/caption]

New investigations of lunar samples collected during the Apollo missions have revealed origins from beyond the Earth-Moon system, supporting a hypothesis of ancient cataclysmic bombardment for both worlds.

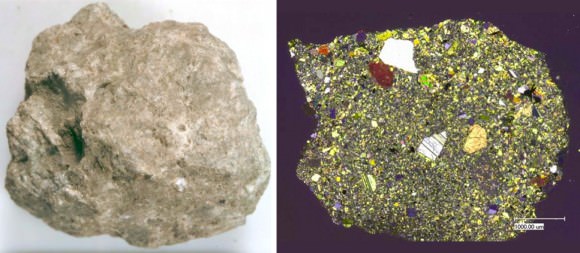

Using scanning electron microscopes, researchers at the Lunar-Planetary Institute and Johnson Space Center have re-examined breccia regolith samples returned from the Moon, chemically mapping the lunar rocks to discern more compositional detail than ever before.

What they discovered was that many of the rocks contain bits of material that is chondritic in origin — that is, it came from asteroids, and not from elsewhere on the Moon or Earth.

Chondrites are meteorites that originate from the oldest asteroids, formed during the development of the Solar System. They are composed of the initial material that made up the stellar disk, compressed into spherical chondrules. Chondrites are some of the rarest types of meteorites found on Earth today but it’s thought that at one time they rained down onto our planet… as well as our moon.

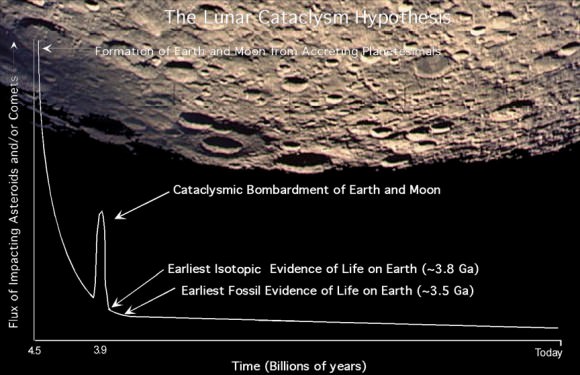

The Lunar Cataclysm Hypothesis suggests that there was a period of extremely active bombardment of the Moon’s surface by meteorite impacts around 3.9 billion years ago. Because very few large impact events — based on melt rock samples — seem to have taken place more than 3.85 billion years ago, scientists suspect such an event heated the Moon’s surface enough prior to that period to eradicate any older impact features — a literal resurfacing of the young Moon.

There’s also evidence that there was a common source for the impactors, based on composition of the chondrites. What event took place in the Solar System that sent so much material hurtling our way? Was there a massive collision between asteroids? Did a slew of comets come streaking into the inner solar system? Were we paid a brief, gravitationally-disruptive visit by some other rogue interstellar object? Whatever it was that occurred, it changed the face of our Moon forever.

Curiously enough, it was at just about that time that we find the first fossil evidence of life on Earth. If there’s indeed a correlation, then whatever happened to wipe out the Moon’s oldest craters may also have cleared the slate for life here — either by removing any initial biological development that may have occurred or by delivering organic materials necessary for life in large amounts… or perhaps a combination of both.

The new findings from the Apollo samples provide unambiguous evidence that a large-scale impact event was taking place during this period on the Moon — and most likely on Earth too. Since the Moon lacks atmospheric weathering or water erosion processes it serves as a sort of “time capsule”, recording the evidence of cosmic events that take place around the Earth-Moon neighborhood. While evidence for any such impacts would have long been erased from Earth’s surface, on the Moon it’s just a matter of locating it.

In fact, due to the difference in surface area, Earth may have received up to ten times more impacts than the Moon during such a cosmic cataclysm. With over 1,700 craters over 20 km identified on the Moon dating to a period around 3.9 billion years ago, Earth should have 17,000 craters over 20 km… with some ranging over 1,000 km! Of course, that’s if the craters could had survived 3.9 billion years of erosion and tectonic activity, which they didn’t. Still, it would have been a major event for our planet and anything that may have managed to start eking out an existence on it. We might never know if life had gained a foothold on Earth prior to such a cataclysmic bombardment, but thanks to the Moon (and the Apollo missions!) we do have some evidence of the events that took place.

The LPI-JSC team’s paper was submitted to the journal Science and accepted for publication on May 2. See the abstract here, and read more on the Lunar Science Institute’s website here.

And if you want to browse through the Apollo lunar samples you can do so in depth on the JSC Lunar Sample Compendum site.