My son recently came back from a science day camp with one of the coolest things. It was a model of the Earth that he had created out of modeling clay. It showed the internal structure of the Earth, and because he built it, he was able to remember all of the layers of the Earth. Very cool. So here’s a good way to learn the Earth layers for kids.

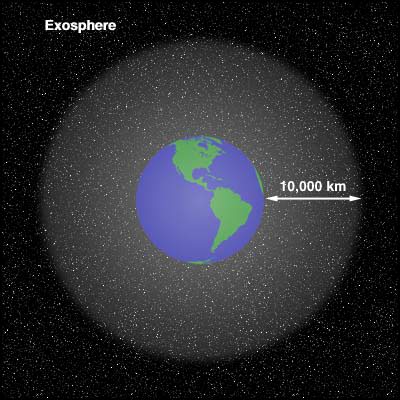

To make your own, you need some modeling clay of different colors. You start by making a ball about 1.2 cm across. This represents the Earth’s inner core. Then you make a second ball about 3 cm across. This ball represents the Earth’s outer core. Then you make a third ball about 6 cm across. This ball represents the Earth’s mantle. And finally, you make some flattened pieces of clay that will be the Earth’s crust. To make it extra realistic, make some pieces blue and others green.

Take inner core and surround it with the outer core, and then surround that by the mantle. Cover the entire mantle with a thin layer of blue, and then put on some green continents on top of the blue.

If you’ve been really careful, you should be able to take a sharp knife and slice your Earth ball in half. You should be able to see the Earth’s layers inside, just like you’d see the real Earth’s layers. And you can see that the mantle is thicker underneath the Earth’s continents than it is under the oceans.

Here’s a link with more information from Purdue University so you can do the experiment yourself.

If you’re interested in teaching your children Earth science, here’s lots of information about volcanoes for kids.

We have also recorded a whole episode of Astronomy Cast just about Earth. Listen here, Episode 51: Earth.