Would shooting a black hole into an antimatter black hole destroy them both?

Continue reading “What if a Black Hole Met an Antimatter Black Hole?”

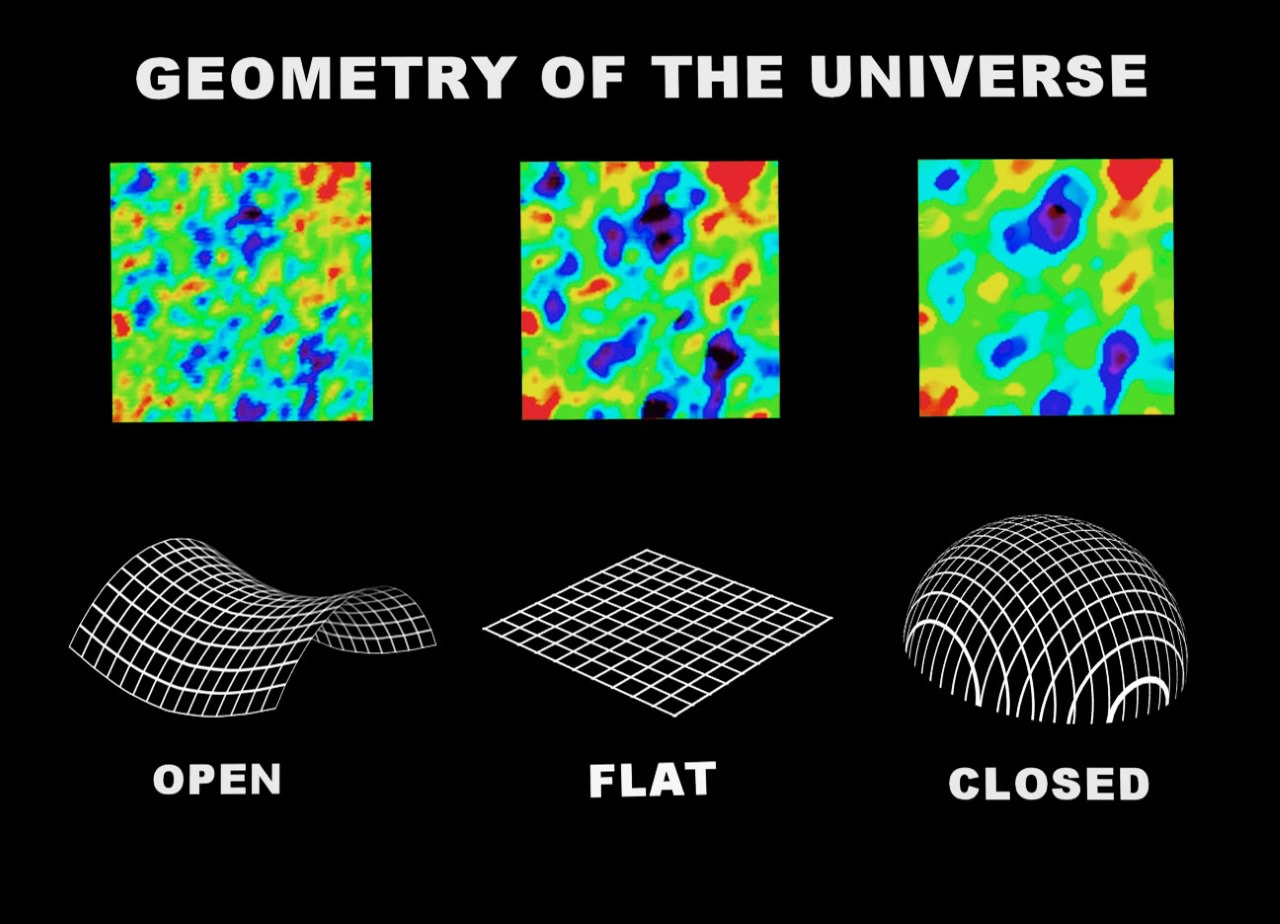

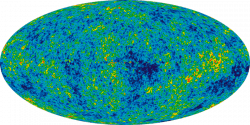

What Shape is the Universe?

It’s a reasonable question to wonder what the shape of the Universe is. Is it a sphere? A torus? Is it open or closed, or flat? And what does that all mean anyway?

The Universe. It’s the only home we’ve ever known. Thanks to its intrinsic physical laws, the known constants of nature, and the heavy-metal-spewing fireballs known as supernovae we are little tiny beings held fast to a spinning ball of rock in a distant corner of space and time.

Doesn’t it seem a little rude not to know much about the Universe itself? For instance, if we could look at it from outside, what would we see? A vast blackness? A sea of bubbles? Snow globe? Rat maze? A marble in the hands of a larger-dimensional aliens or some other prog rock album cover?

As it turns out, the answer is both simpler and weirder than all those options. What does the Universe look like is a question we love to guess at as a species and make up all kinds of nonsense.

Hindu texts describe the Universe as a cosmic egg, the Jains believed it was human-shaped. The Greek Stoics saw the Universe as a single island floating in an otherwise infinite void, while Aristotle believed it was made up of a finite series of concentric spheres, or perhaps it’s simply “turtles all the way down”.

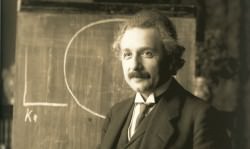

Thanks to the mathematical genius of Einstein, cosmologists can actually test out the validity of various models that describe the Universe’s shape, turtles, mazes, and otherwise.

There are three main flavors that scientists consider: positively-curved, negatively-curved, and flat. We know it exists in at least four dimensions, so any of the shapes we are about to describe are bordering on Lovecraftian madness geometry, so fire up your madness abacus. Ya! Ya! Cthulhu ftagen.

A positively-curved Universe would look somewhat like a four-dimensional sphere. This type of Universe would be finite in space, but with no discernible edge. In fact, two distant particles travelling in two straight lines would actually intersect before ending up back where they started.

You can try this at home. Grab a balloon and draw a straight line with a sharpie. Your line eventually meets its starting point. A second line starting on the opposite side of the balloon will do the same thing, and it will cross your first line before meeting itself again.

This type of Universe, conveniently easy to imagine in three dimensions – would only arise if the cosmos contained a certain, large amount of energy.

To be positively-curved, or closed, the Universe would first have to stop expanding – something that would only happen if the cosmos housed enough energy to give gravity the leading edge. Present cosmological observations suggest that the Universe should expand forever. So, for now, we’re tossing out the easy to imagine scenario.

A negatively-curved Universe would look like a four-dimensional saddle. Open, without boundaries in space or time. It would contain too little energy to ever stop expanding.

Here two particles traveling on straight paths would never meet. In fact, they would continuously diverge, getting farther and farther away from each other as infinite time spiraled on.

If the Universe is found to contain a Goldilocks-specific, critical amount of energy, teetering perilously between the extremes, its expansion will halt after an infinite amount of time,

This type of Universe is called a flat Universe. Particles in a flat cosmos continue on their merry way in parallel straight paths, never to meet, but never to diverge either.

Sphere, saddle, flat plane. Those are pretty easily to picture. There are other options too – like a soccer ball, a doughnut, or a trumpet.

A soccer ball would look much like a spherical Universe, but one with a very particular signature – a sort of hall of mirrors imprinted on the cosmic microwave background.

The doughnut is technically a flat Universe, but one that is connected in multiple places. Some scientists believe that large warm and cool spots in the CMB could actually be evidence for this kind of tasty topology.

Lastly, we come to the trumpet. This is another way to visualize a negatively-curved cosmos: like a saddle curled into a long tube, with one very flared end and one very narrow end. Someone in the narrow end would find their cosmos to be so cramped, it only had two dimensions. Meanwhile, someone else in the flared end could only travel so far before they found themselves inexplicably turned around and flying the other way.

So which is it? Is our Universe an orange or a bagel? Is it Pringles? A cheese slice? Brass or woodwind? Scientists have not yet ruled out the more wacky, negatively-curved suggestions, such as the saddle or the trumpet.

Haters are going to argue that we will never know what the true shape of our Universe is. Those people are no fun, and are just obstructionists. Seriously, let us help you get better friends.

Based on the most recent Planck data, released in February 2015, our Universe is most likely… Flat. Infinitely finite, not curved even a little bit, with an exact, critical amount of energy supplied by dark matter and dark energy.

I know this gets a little confusing, and meanders right up to the border of nap time, but here’s what I’m hoping you’ll take away from all this.

It’s amazing that not only can we make guesses at what our incredible universe looks like, but that there’s clever people working tirelessly to help us figure that out. It’s one of the things that makes me happiest about talking every week about space and astronomy. I just can’t wait to see what’s next.

So what do you think? Is a flat Universe too boring for your taste? What shape would you like the Universe to be, given the wide array of options?

Thanks for watching! Never miss an episode by clicking subscribe.

Our Patreon community is the reason these shows happen. We’d like to thank Fred Manzella, Todd Sanders, and the rest of the members who support us in making great space and astronomy content. Members get advance access to episodes, extras, contests, and other shenanigans with Jay, myself and the rest of the team.

Want to get in on the action? Click here.

Astronomy Cast Ep. 371: The Eddington Eclipse Experiment

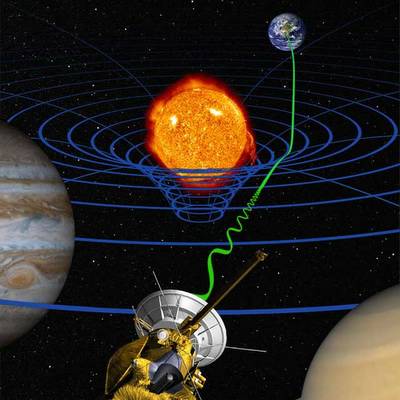

At the turn of the 20th Century, Einstein’s theory of relativity stunned the physics world, but the experimental evidence needed to be found. And so, in 1919, another respected astronomer, Arthur Eddington, observed the deflection of stars by the gravity of the Sun during a solar eclipse. Here’s the story of that famous experiment.

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 371: The Eddington Eclipse Experiment”

Astronomy Cast Ep. 370: The Kaufmann–Bucherer–Neumann Experiments

One of the most amazing implications of Einstein’s relativity is the fact that the inertial mass of an object depends on its velocity. That sounds like a difficult thing to test, but that’s exactly what happened through a series of experiments performed by Kaufmann, Bucherer, Neumann and others.

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 370: The Kaufmann–Bucherer–Neumann Experiments”

How Do We Know Dark Energy Exists?

We have no idea what it dark energy is, so how are we pretty sure it exists?

I’ve talked about how astronomers know that dark matter exists. Even though they can’t see it, they detect it through the effect its gravity has on light. Dark matter accounts for 27% of the Universe, dark energy accounts for 68% of the Universe. And again, astronomers really have no idea what what it is, only that they’re pretty sure it does exist. 95% of the nature of the Universe is a complete and total mystery. We just have no idea what this stuff is.

So this time around, lets focus on dark energy. Back in the late 90s, astronomers wanted to calculate once and for all if the Universe was open or closed. In other words, they wanted to calculate the rate of expansion of the Universe now and then compare this rate to its expansion in the past. In order to answer this question, they searched the skies for a special type of supernova known as a Type 1a.

While most supernovae are just massive stars, Type 1a are white dwarf stars that exist in a binary system. The white dwarf siphons material off of its binary partner, and when it reaches 1.6 times the mass of the Sun, it explodes. The trick is that these always explode with roughly the same amount of energy. So if you measure the brightness of a Type 1a supernova, you know roughly how far away it is.

Astronomers assumed the expansion was slowing down. But the question was, how fast was it slowing down? Would it slow to a halt and maybe even reverse direction? So, what did they discover?

In the immortal words of Isaac Asimov, “the most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not ‘Eureka’, but ‘That’s Funny’” Instead of finding that the expansion of the Universe was slowing down, they discovered that it’s speeding up. That’s like trying to calculate how quickly apples fall from trees and finding that they actually fly off into the sky, faster and faster.

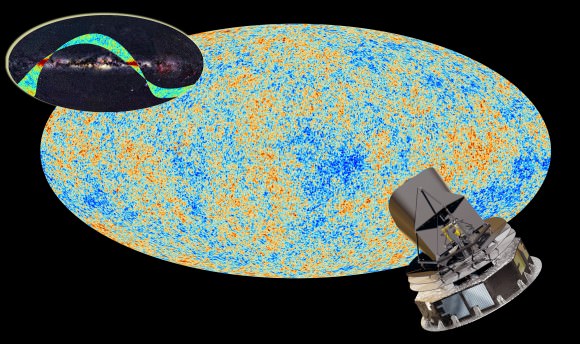

Since this amazing, Nobel prize winning discovery, astronomers have used several other methods to verify this mind-bending reality of the Universe. NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe studied the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation of the Universe for 7 years, and put the amount of dark energy at 72.8% of the Universe. ESA’s Planck spacecraft performed an even more careful analysis and pegged that number at 68.3% of the Universe.

Astronomers know that dark energy exists. There are multiple lines of evidence. But as with dark matter, they have absolutely no clue what it is. Einstein described an idea he called the cosmological constant. It was a way to explain a static Universe that really should be expanding or contracting. Once astronomers figured out the Universe was actually expanding, he threw the idea out.

Hey, not so fast there “Einstein”. Maybe just one of the features of space itself is that it pushes stuff away. And the more space there is, the more outward pressure you get. Perhaps from virtual particles popping in and out of existence in the vacuum of space.

Another possibility is a phenomenon called Quintessence, a negative energy field that pervades the entire Universe. Yes, that sounds totally woo-woo, thanks Universe, Deepak Chopra crazy talk, but it might explain the repulsive force that makes up most of the Universe. And there are other theories, which are even more exotic. But mostly likely it’s something that physicists haven’t even thought of yet.

So, how do we know dark energy exists? Distant supernovae are a lot further away from each other than they should be if the expansion of the Universe was slowing down. Nobody has any idea what it is, it’s a mystery, and there’s nothing wrong with a mystery. In fact, for me, it’s one of the most exciting ideas in space and astronomy.

What do you think dark energy is?

How We’ve ‘Morphed’ From “Starry Night” to Planck’s View of the BICEP2 Field

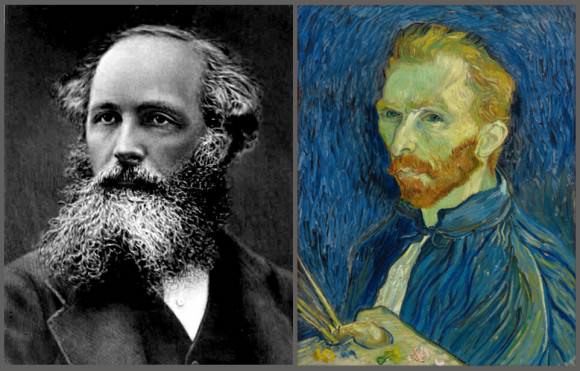

From the vantage point of a window in an insane asylum, Vincent van Gogh painted one of the most noted and valued artistic works in human history. It was the summer of 1889. With his post-impressionist paint strokes, Starry Night depicts a night sky before sunrise that undulates, flows and is never settled. Scientific discoveries are revealing a Cosmos with such characteristics.

Since Vincent’s time, artists and scientists have taken their respective paths to convey and understand the natural world. The latest released images taken by the European Planck Space Telescope reveals new exquisite details of our Universe that begin to touch upon the paint strokes of the great master and at the same time looks back nearly to the beginning of time. Since Van Gogh – the passage of 125 years – scientists have constructed a progressively intricate and incredible description of the Universe.

The path from Van Gogh to the Planck Telescope imagery is indirect, an abstraction akin to the impressionism of van Gogh’s era. Impressionists in the 1800s showed us that the human mind could interpret and imagine the world beyond the limitations of our five senses. Furthermore, optics since the time of Galileo had begun to extend the capability of our senses.

Mathematics is perhaps the greatest form of abstraction of our vision of the World, the Cosmos. The path of science from the era of van Gogh began with his contemporary, James Clerk Maxwell who owes inspiration from the experimentalist Michael Faraday. The Maxwell equations mathematically define the nature of electricity and magnetism. Since Maxwell, electricity, magnetism and light have been intertwined. His equations are now a derivative of a more universal equation – the Standard Model of the Universe. The accompanying Universe Today article by Ramin Skibba describes in more detail the new findings by Planck Mission scientists and its impact on the Standard Model.

The work of Maxwell and experimentalists such as Faraday, Michelson and Morley built an overwhelming body of knowledge upon which Albert Einstein was able to write his papers of 1905, his miracle year (Annus mirabilis). His theories of the Universe have been interpreted, verified time and again and lead directly to the Universe studied by scientists employing the Planck Telescope.

In 1908, the German physicist Max Planck, for whom the ESA telescope is named, recognized the importance of Einstein’s work and finally invited him to Berlin and away from the obscurity of a patent office in Bern, Switzerland.

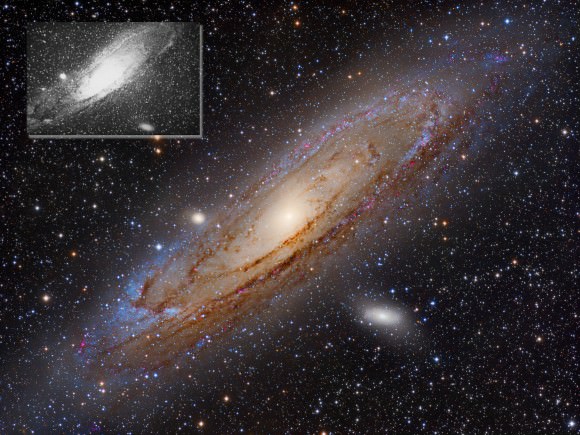

As Einstein spent a decade to complete his greatest work, the General Theory of Relativity, astronomers began to apply more powerful tools to their trade. Edwin Hubble, born in the year van Gogh painted Starry Night, began to observe the night sky with the most powerful telescope in the World, the Mt Wilson 100 inch Hooker Telescope. In the 1920s, Hubble discovered that the Milky Way was not the whole Universe but rather an island universe, one amongst billions of galaxies. His observations revealed that the Milky Way was a spiral galaxy of a form similar to neighboring galaxies, for example, M31, the Andromeda Galaxy.

Einstein’s equations and Picasso’s abstraction created another rush of discovery and expressionism that propel us for another 50 years. Their influence continues to impact our lives today.

Telescopes of Hubble’s era reached their peak with the Palomar 200 inch telescope, four times the light gathering power of Mount Wilson’s. Astronomy had to await the development of modern electronics. Improvements in photographic techniques would pale in comparison to what was to come.

The development of electronics was accelerated by the pressures placed upon opposing forces during World War II. Karl Jansky developed radio astronomy in the 1930s which benefited from research that followed during the war years. Jansky detected the radio signature of the Milky Way. As Maxwell and others imagined, astronomy began to expand beyond just visible light – into the infrared and radio waves. Discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) in 1964 by Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson is arguably the greatest discovery from observations in the radio wave (and microwave) region of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Analog electronics could augment photographic studies. Vacuum tubes led to photo-multiplier tubes that could count photons and measure more accurately the dynamics of stars and the spectral imagery of planets, nebulas and whole galaxies. Then in the 1947, three physicists at Bell Labs , John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley created the transistor that continues to transform the World today.

For astronomy and our image of the Universe, it meant more acute imagery of the Universe and imagery spanning across the whole electromagnetic spectrum. Infrared Astronomy developed slowly beginning in the 1800s but it was solid state electronics in the 1960s when it came of age. Microwave or Millimeter Radio Astronomy required a marriage of radio astronomy and solid state electronics. The first practical millimeter wave telescope began operations in 1980 at Kitt Peak Observatory.

With further improvements in solid state electronics and development of extremely accurate timing devices and development of low-temperature solid state electronics, astronomy has reached the present day. With modern rocketry, sensitive devices such as the Hubble and Planck Space Telescopes have been lofted into orbit and above the opaque atmosphere surrounding the Earth.

Astronomers and physicists now probe the Universe across the whole electromagnetic spectrum generating terabytes of data and abstractions of the raw data allow us to look out into the Universe with effectively a sixth sense, that which is given to us by 21st century technology. What a remarkable coincidence that the observations of our best telescopes peering through hundreds of thousands of light years, even more so, back 13.8 billion years to the beginning of time, reveal images of the Universe that are not unlike the brilliant and beautiful paintings of a human with a mind that gave him no choice but to see the world differently.

Now 125 years later, this sixth sense forces us to see the World in a similar light. Peer up into the sky and you can imagine the planetary systems revolving around nearly every star, swirling clouds of spiral galaxies, one even larger in the sky than our Moon, and waves of magnetic fields everywhere across the starry night.

Consider what the Planck Mission is revealing, questions it is answering and new ones it is raising – It Turns Out Primordial Gravitational Waves Weren’t Found.

How are Energy and Matter the Same?

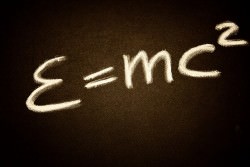

As Einstein showed us, light and matter and just aspects of the same thing. Matter is just frozen light. And light is matter on the move. How does one become the other?

Albert Einstein’s most famous equation says that energy and matter are two sides of the same coin.

But what does that really mean? And how are equations famous? I like to believe equations can be famous in the way a work of art, or a philosophy can be famous. People can have awareness of the thing, and yet never have interacted with it. They can understand that it is important, and yet not understand why it’s so significant. Which is a little too bad, as this is really a lovely mind bending idea.

The origin of E=mc2 lies in special relativity. Light has the same speed no matter what frame of reference you are in. No matter where you are, or how fast you’re going. If you were standing still at the side of the road, and observed a car traveling at ¾ light speed, you would see the light from their headlights traveling away from them at ¼ the speed of light.

But the driver of the car would still see that the light moving ahead of them at the speed of light. This is only possible if their time appears to slow down relative to you, and you and the people in the car can no longer agree on how long a second would take to pass.

So the light appears to be moving away from them more slowly, but as they experience things more slowly it all evens out. This also affects their apparent mass. If they step on the gas, they will speed up more slowly than you would expect. It’s as if the car has more mass than you expect. So relativity requires that the faster an object moves, the more mass it appears to have. This means that somehow part of the energy of the car’s motion appears to transform into mass. Hence the origin of Einstein’s equation. How does that happen? We don’t really know. We only know that it does.

The same effect occurs with quantum particles, and not just with light. A neutron, for example, can decay into a proton, electron and anti-neutrino. The mass of these three particles is less than the mass of a neutron, so they each get some energy as well. So energy and matter are really the same thing. Completely interchangeable. And finally, Although energy and mass are related through special relativity, mass and space are related through general relativity. You can define any mass by a distance known as its Schwarzschild radius, which is the radius of a black hole of that mass. So in a way, energy, matter, space and time are all aspects of the same thing.

What do you think? Like E=mc2, what’s the most famous idea you can think of in physics?

And if you like what you see, come check out our Patreon page and find out how you can get these videos early while helping us bring you more great content!

What Time is It in the Universe?

Check your watch, what time is it? But wait, you’ve actually been moving and accelerating, and according to Einstein, everything’s relative. So what time is it really? It all depends…

Flavor Flav knows what time it is. At least he does for Flavor Flav. Even with all his moving and accelerating, with the planet, the solar system, getting on planes, taking elevators, and perhaps even some light jogging. In the immortal words of Kool Moe Dee. Do you know what time it is?

Didn’t Einstein tell us it’s all relative? Does anyone actually know what time it is? I mean, aside from figuratively, or in a political sense, or perhaps as part of rap performance from whence the power is being fought from, requiring the sick skills of a hype man wearing a clock around his neck on a big chain.

So, after all my fancy dancing and longing for a time in rap and hip hop from days gone by, I must present to you “faithful audience member” an answer in the form of your 3 least favorite words I get to deliver.

It all depends…

You have heard that everything is relative, usually we hear it from people who like to talk about “connections on many different levels”, which is just nonsense.

But in physics “everything” is relative in a very particular way. Everything is relative to the speed of light, which is the same in every reference frame. Which is confusing and repeated enough that it can become meaningless.

So I’m going to do my best to explain it. If I shine a flashlight in front of me, I will measure the beam to travel at about 300,000 km/s, which is also known as the speed of light.

And if you are moving at 200,000 km/s faster than me, and shine a flashlight ahead of you, I will see the light from your flashlight moving at the 300,000km/s. It will appear to me, as though the light from your flashlight is moving away from you at 100,000 km/s.

But when you will measure the speed of that light, relative to you, you’d think it’d be moving at 100,000 km/s as well, but instead from your perspective it will ALSO clock in at 300,000 km/s.

The speed of light. How is this even possible? It is possible in part because the rate at which you experience time relative to me changes. For you, time will seem normal, but from my perspective your time will seem slower. We agree on how fast light is moving in kilometers per second, but we disagree how long a second is. We also, by the way, disagree on the length of a meter.

This seems strange because we imagine that space and time are absolute things, and light is something that travels through space. This is our experience. Suggesting things like time and space are malleable values at best is unsettling and at worst will make us nanners from thinking too much about.

Hold on to your tinfoil hats, for it is in fact light that is the absolute, and space and time are relative to it. So what time it is depends upon your vantage point, and so there is no single absolute time.

Finally, because of relativity, each point in the Universe experiences time at a slightly different rate. For example, when we observe the cosmic microwave background, we find that we are moving at a speed of about 630 km/s relative to the background. That means we experience time a bit more slowly that something at rest relative to the cosmic background.

It’s just a tiny bit slower, but added over the entire age of the Universe, our cosmic clock is 30,000 years behind the times. Feel free to set your watch. But don’t get too precise about it. Your time could be off by tens of thousands of years.

What about you? What’s your favorite way to explain special relativity to someone. Tell us in the comments below.

Does Light Experience Time?

Have you ever noticed that time flies when you’re having fun? Well, not for light. In fact, photons don’t experience any time at all. Here’s a mind-bending concept that should shatter your brain into pieces.

As you might know, I co-host Astronomy Cast, and get to pick the brain of the brilliant astrophysicist Dr. Pamela Gay every week about whatever crazy thing I think of in the shower. We were talking about photons one week and she dropped a bombshell on my brain. Photons do not experience time. [SNARK: Are you worried they might get bored?]

Just think about that idea. From the perspective of a photon, there is no such thing as time. It’s emitted, and might exist for hundreds of trillions of years, but for the photon, there’s zero time elapsed between when it’s emitted and when it’s absorbed again. It doesn’t experience distance either. [SNARK: Clearly, it didn’t need to borrow my copy of GQ for the trip.]

Since photons can’t think, we don’t have to worry too much about their existential horror of experiencing neither time nor distance, but it tells us so much about how they’re linked together. Through his Theory of Relativity, Einstein helped us understand how time and distance are connected.

Let’s do a quick review. If we want to travel to some distant point in space, and we travel faster and faster, approaching the speed of light our clocks slow down relative to an observer back on Earth. And yet, we reach our destination more quickly than we would expect. Sure, our mass goes up and there are enormous amounts of energy required, but for this example, we’ll just ignore all that.

If you could travel at a constant acceleration of 1 g, you could cross billions of light years in a single human generation. Of course, your friends back home would have experienced billions of years in your absence, but much like the mass increase and energy required, we won’t worry about them.

The closer you get to light speed, the less time you experience and the shorter a distance you experience. You may recall that these numbers begin to approach zero. According to relativity, mass can never move through the Universe at light speed. Mass will increase to infinity, and the amount of energy required to move it any faster will also be infinite. But for light itself, which is already moving at light speed… You guessed it, the photons reach zero distance and zero time.

Photons can take hundreds of thousands of years to travel from the core of the Sun until they reach the surface and fly off into space. And yet, that final journey, that could take it billions of light years across space, was no different from jumping from atom to atom.

There, now these ideas can haunt your thoughts as they do mine. You’re welcome. What do you think? What’s your favorite mind bending relativity side effect? Tell us in the comments below.

Astronomy Cast Ep. 335: Photoelectric Effect

Pop quiz. How did Einstein win his Nobel prize? Was it for relativity? Nope, Einstein won the Nobel Prize in 1921 for the discovery of the photoelectric effect; how electrons are emitted from atoms when they absorb photons of light. But what is it? Let’s find out.

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 335: Photoelectric Effect”