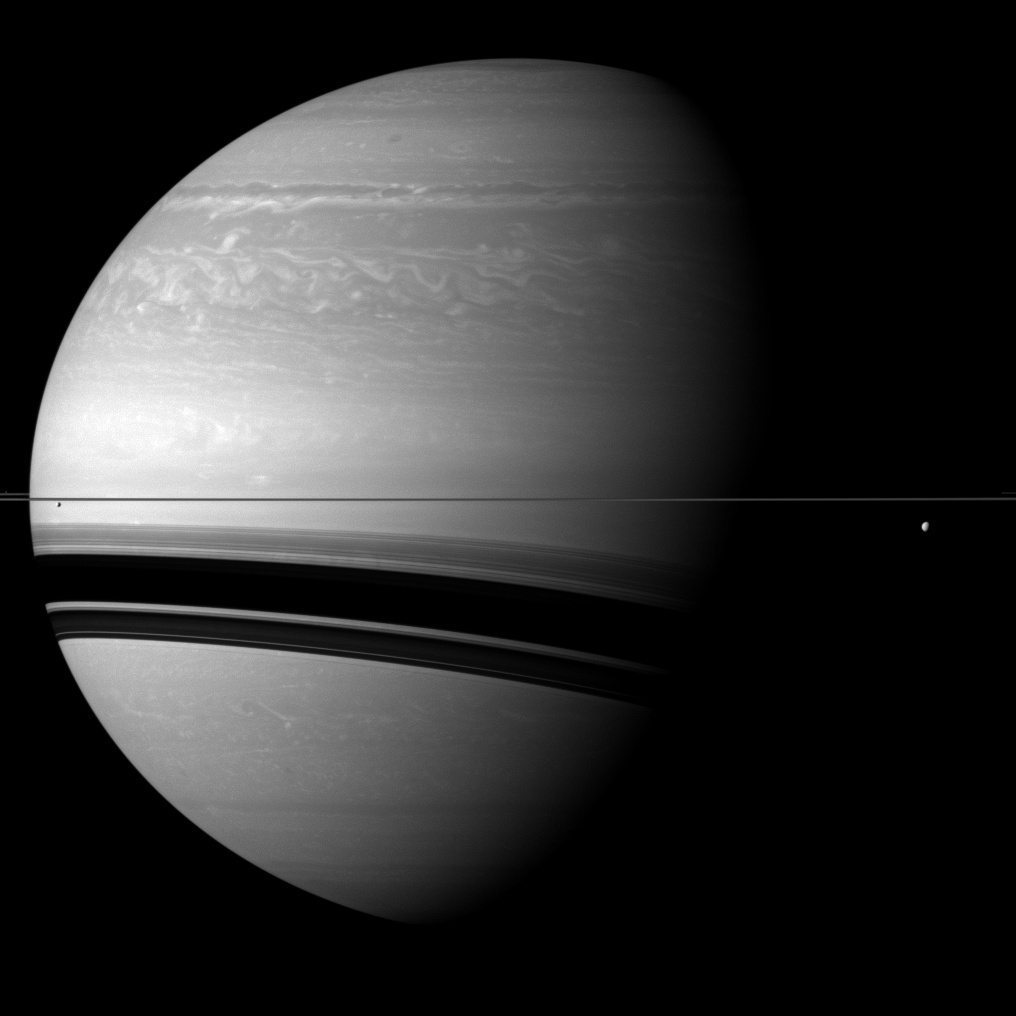

Cassini couldn’t make it to the mall this year to do any Christmas shopping but that’s ok: we’re all getting something even better in our stockings than anything store-bought! To celebrate the holiday season the Cassini team has shared some truly incredible images of Saturn and some of its many moons for the world to “ooh” and “ahh” over. So stoke the fire, pour yourself a glass of egg nog, sit back and marvel at some sights from a wintry wonderland 900 million miles away…

Thanks, Cassini… these are just what I’ve always wanted! (How’d you know?)

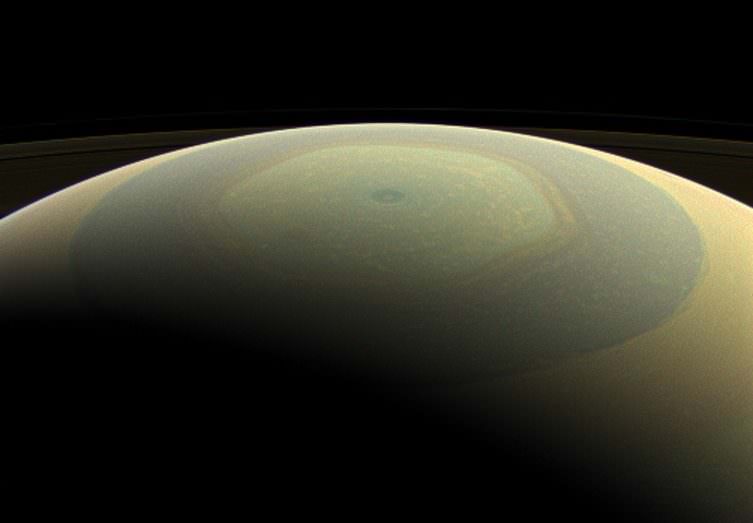

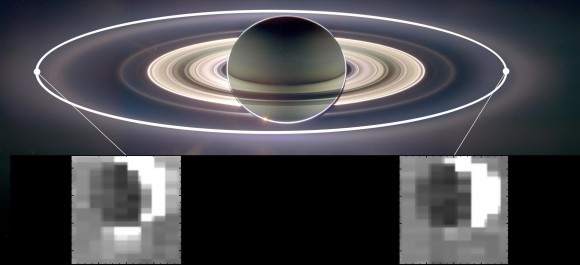

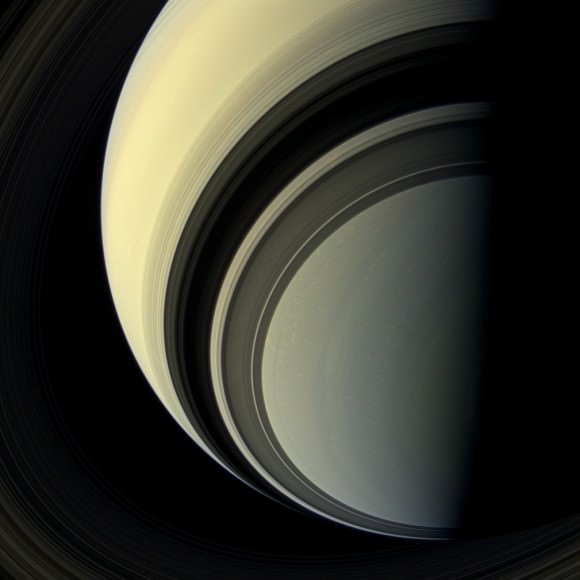

Saturn’s southern hemisphere is growing more and more blue as winter approaches there — a coloration similar to what was once seen in the north when Cassini first arrived in 2004:

(The small dark spot near the center right of the image above is the shadow of the shepherd moon Prometheus.)

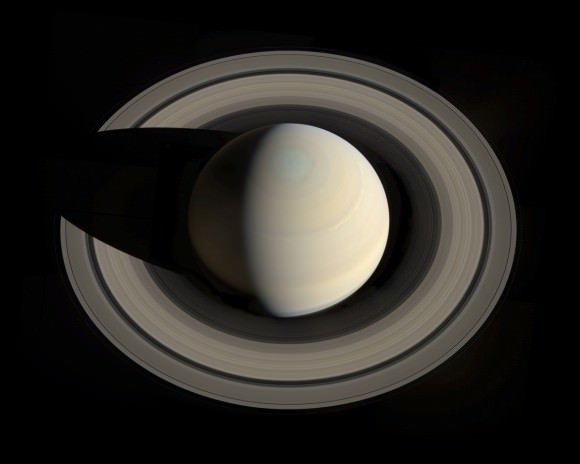

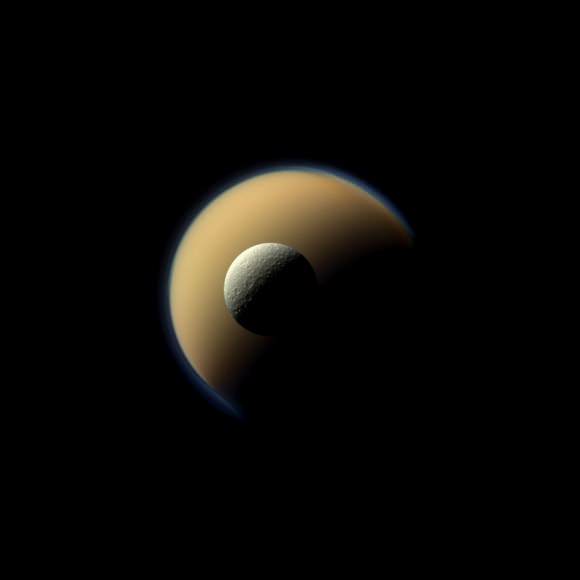

Titan and Rhea, Saturn’s two largest moons, pose for Cassini:

The two moons may look like they’re almost touching but in reality they were nearly half a million miles apart!

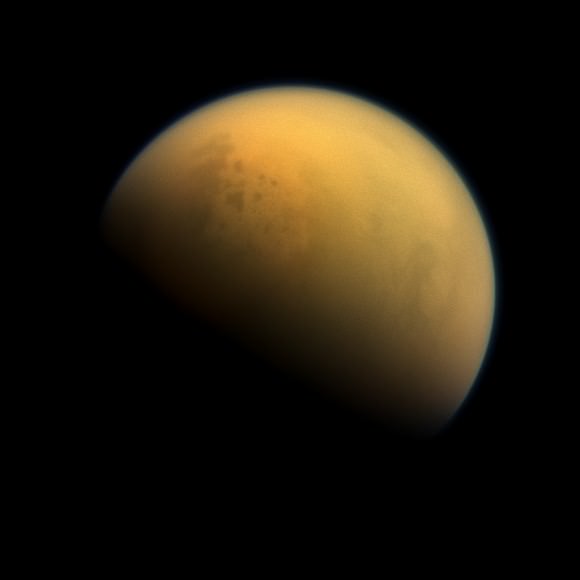

Titan’s northern “land of lakes” is visible in this image, captured by Cassini with a special spectral filter able to pierce through the moon’s thick haze:

Read more: Titan’s North Pole is Loaded with Lakes

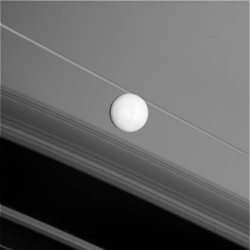

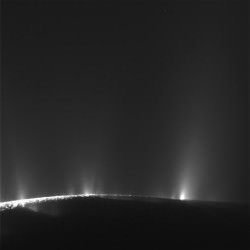

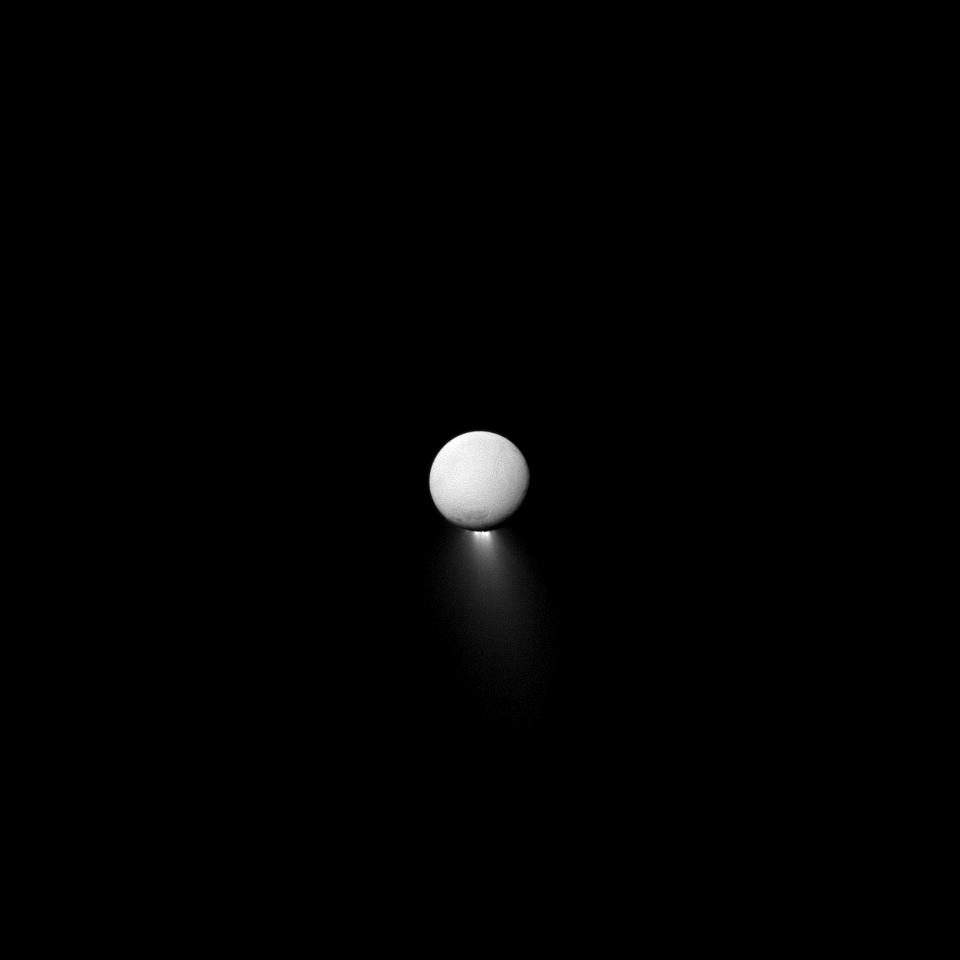

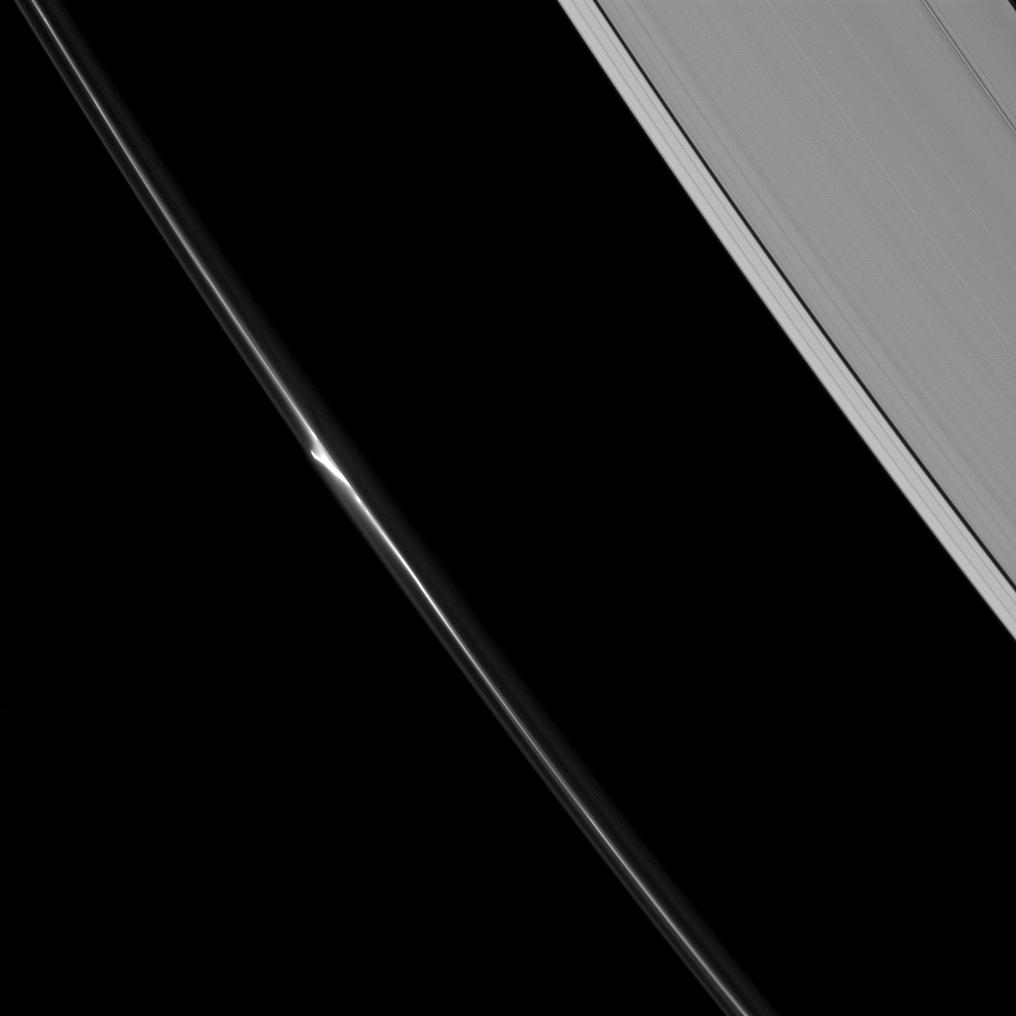

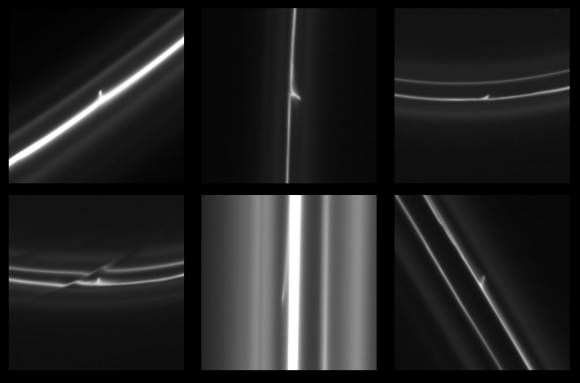

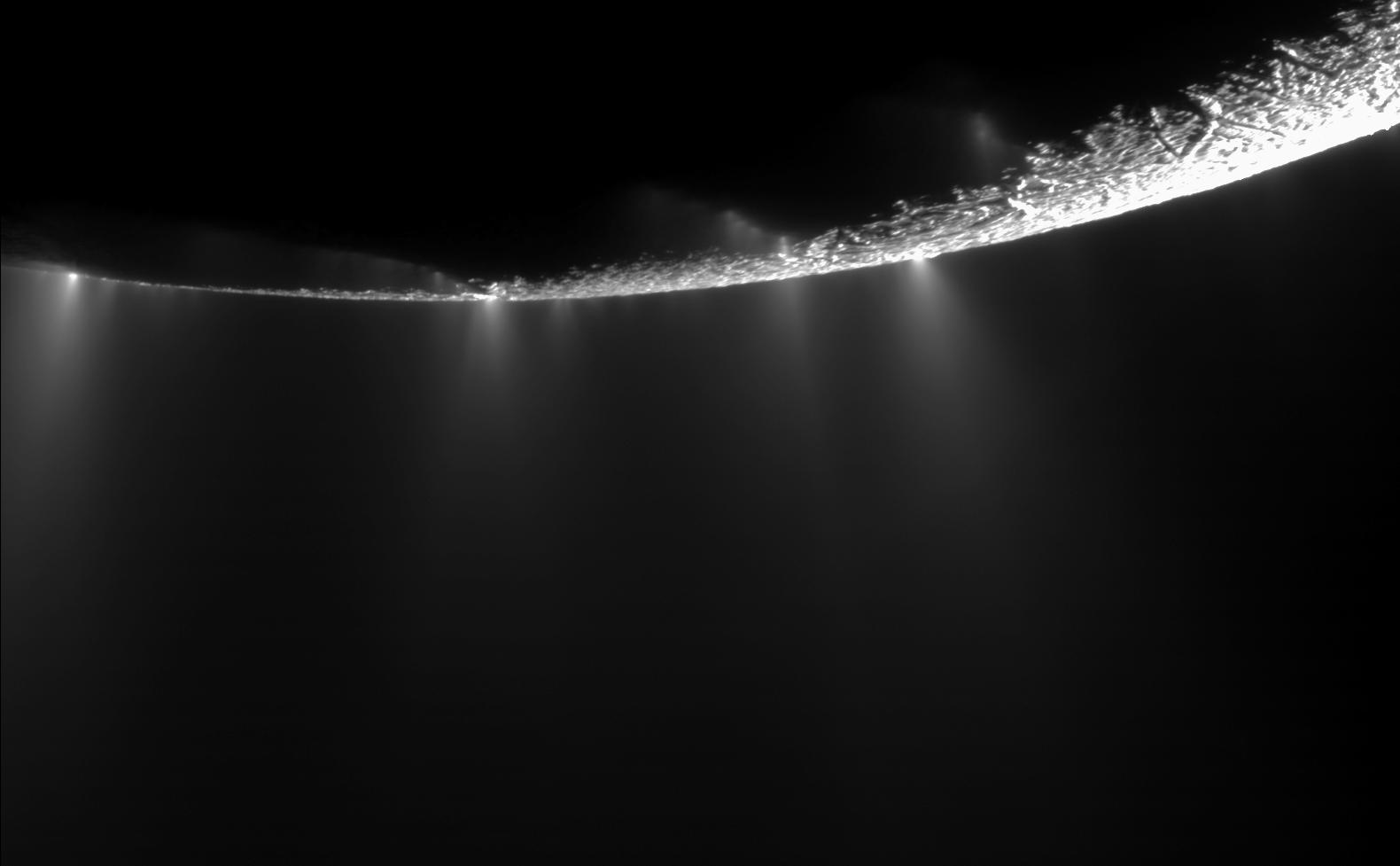

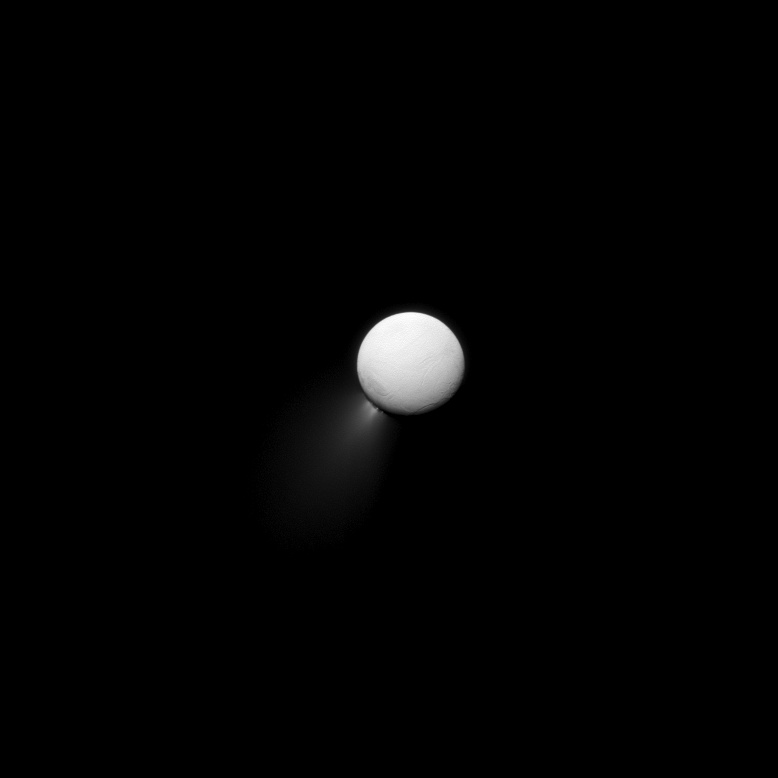

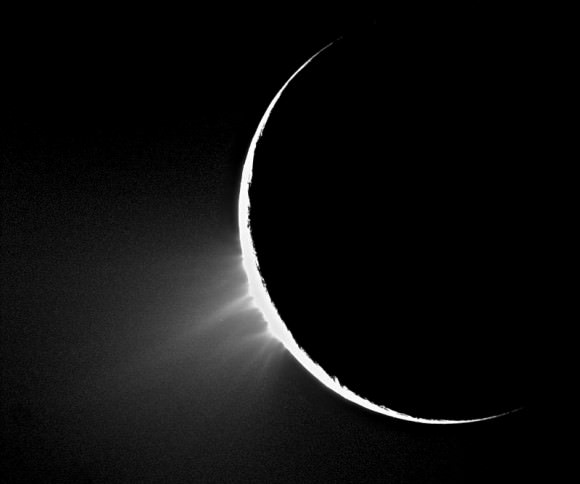

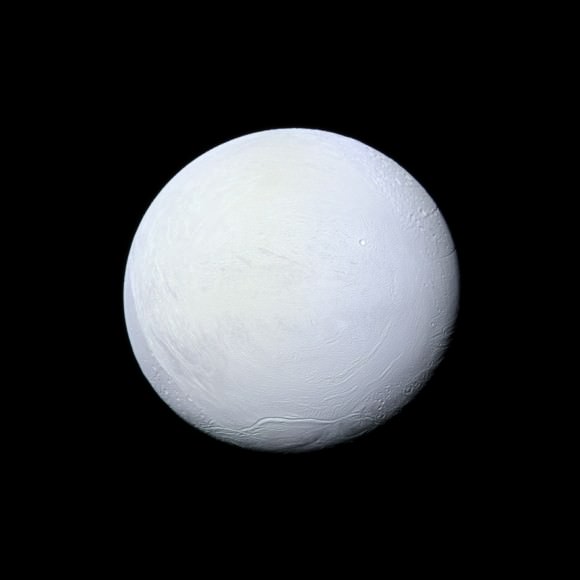

The frozen, snowball-like surface of the 313-mile-wide moon Enceladus:

(Even though Enceladus is most famous for its icy geysers, first observed by Cassini in 2005, in these images they are not visible due to the lighting situations.)

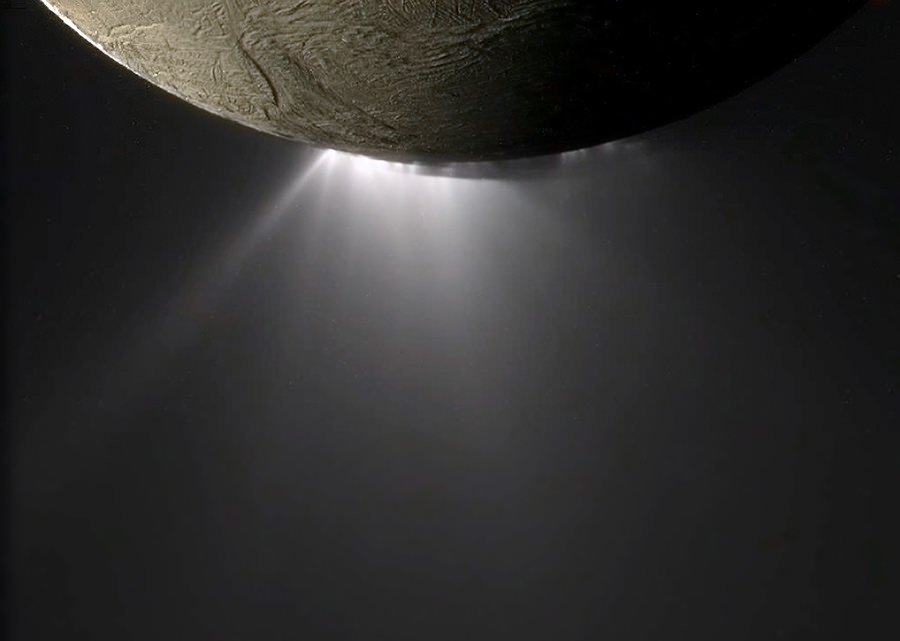

Seen in a different illumination angle and in filters sensitive to UV, visible, and infrared light the many fractures and folds of Enceladus’ frozen surface become apparent:

Because of Cassini’s long-duration, multi-season stay in orbit around Saturn, researchers have been able to learn more about the ringed planet and its fascinating family of moons than ever before possible. Cassini is now going into its tenth year at Saturn and with much more research planned, we can only imagine what discoveries (and images!) are yet to come in the new year(s) ahead.

“Until Cassini arrived at Saturn, we didn’t know about the hydrocarbon lakes of Titan, the active drama of Enceladus’ jets, and the intricate patterns at Saturn’s poles,” said Linda Spilker, the Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “Spectacular images like these highlight that Cassini has given us the gift of knowledge, which we have been so excited to share with everyone.”

Read more about the images above and see even more on the CICLOPS Imaging Team website, and see the NASA press release here.

Thanks to Carolyn Porco, Cassini Imaging Team Leader, for the heads-up on these gifs — er, gifts!