In October of 2018, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will be launched into orbit. As part of NASA’s Next Generation Space Telescope program, the JWST will spend the coming years studying every phase of cosmic history. This will involve probing the first light of the Universe (caused by the Big Bang), the first galaxies to form, and extra-solar planets in nearby star systems.

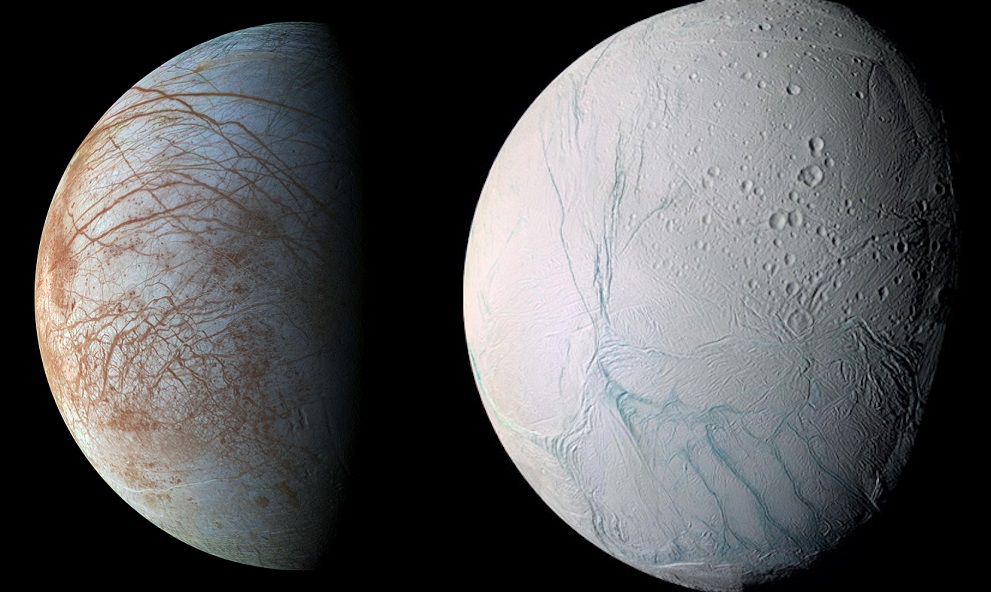

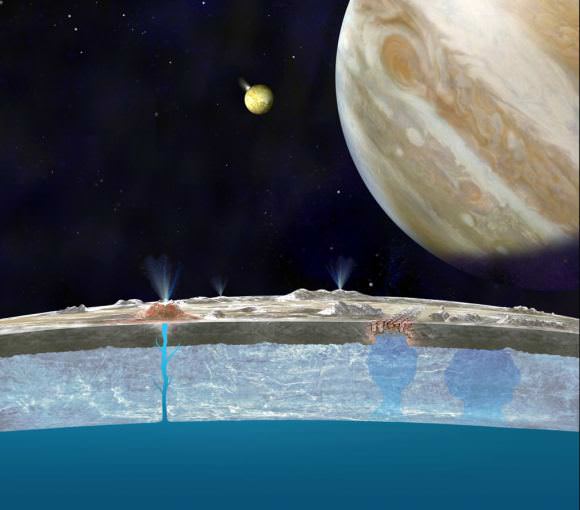

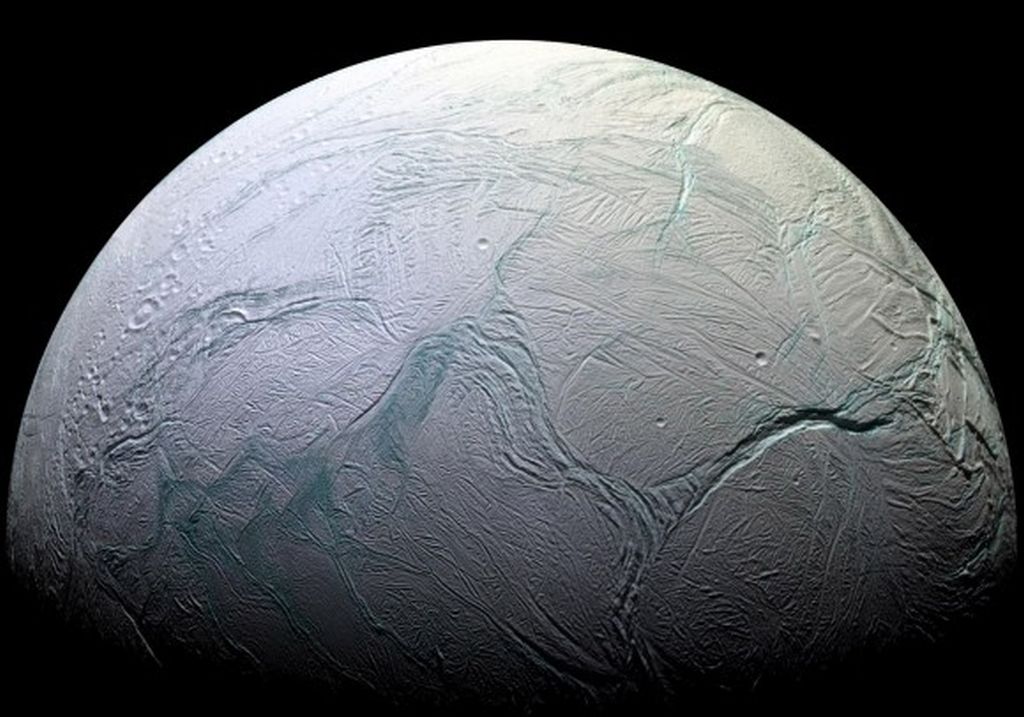

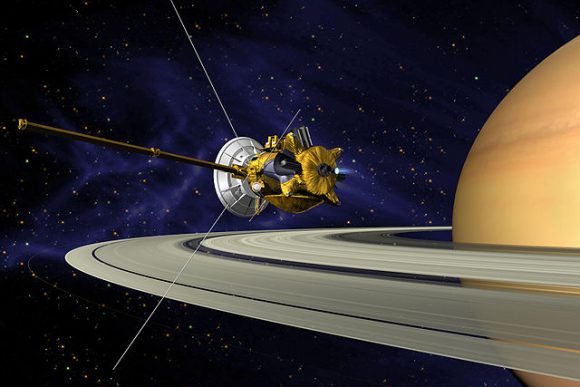

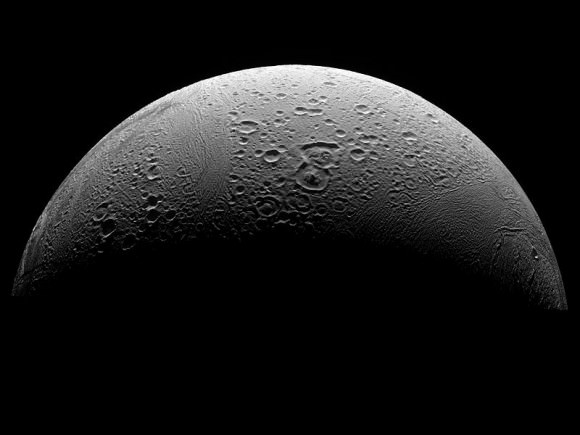

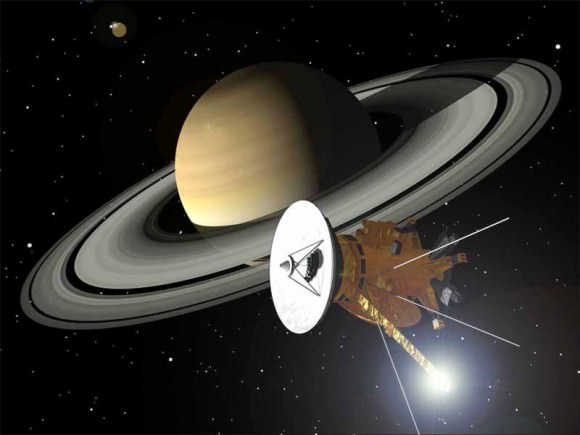

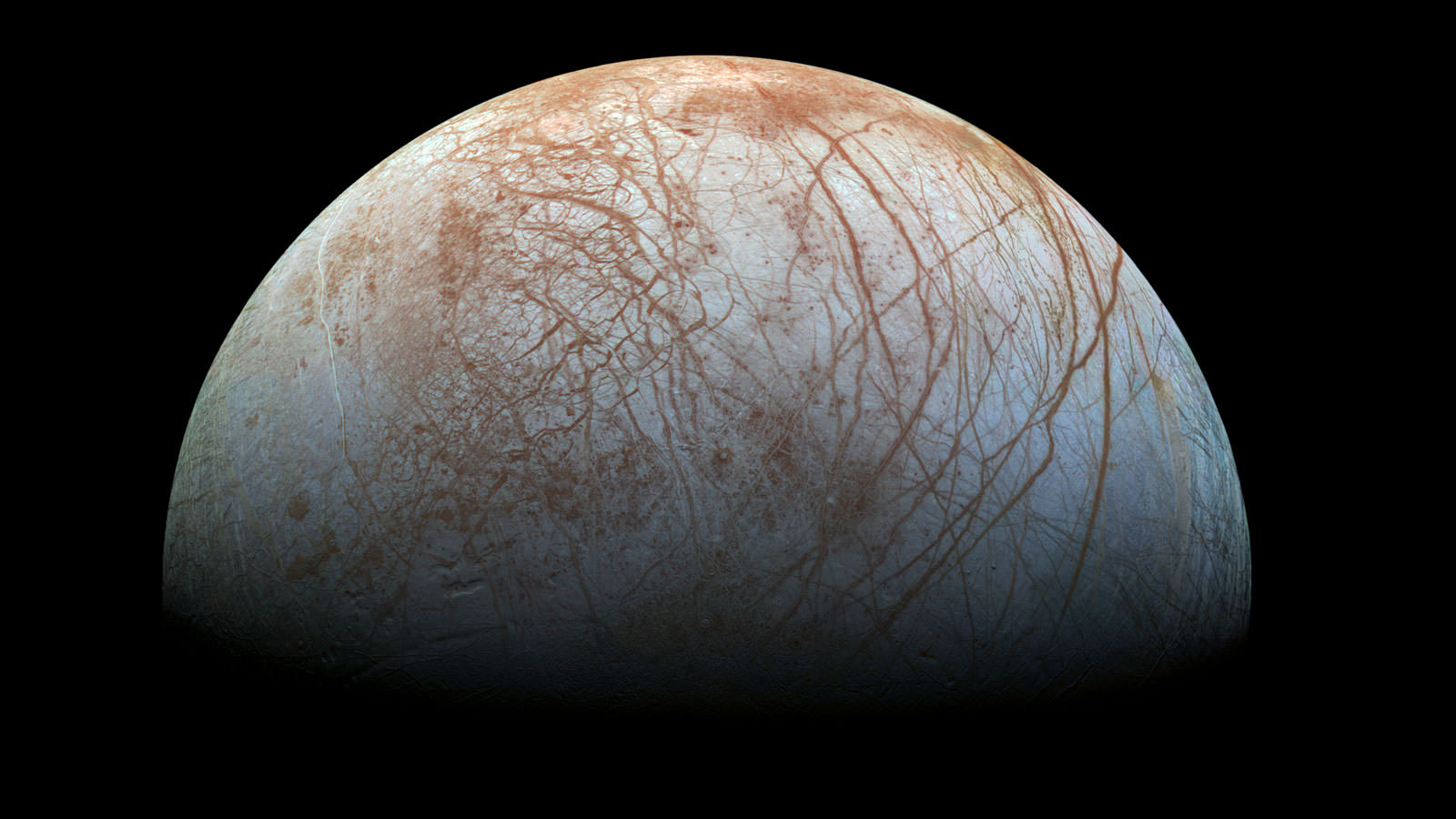

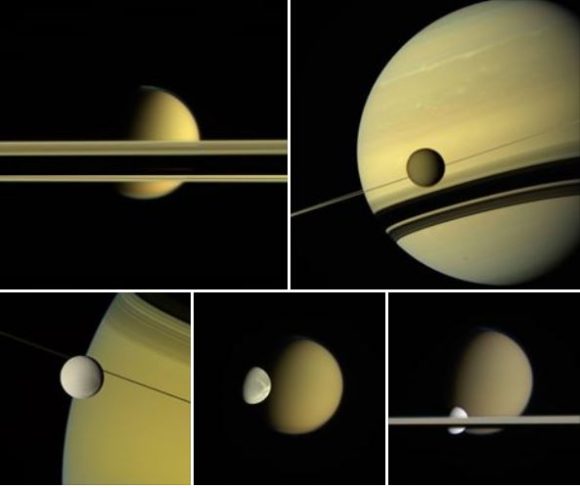

In addition to all of that, the JWST will also be dedicated to studying our Solar System. As NASA recently announced, the telescope will use its infrared capabilities to study two “Ocean Worlds” in our Solar System – Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus. In so doing, it will add to observations previously made by NASA’s Galileo and Cassini orbiters and help guide future missions to these icy moons.

The moons were chosen by scientist who helped to develop the telescope (aka. guaranteed time observers) and are therefore given the privilege of being among the first to use it. Europa and Enceladus were added to the telescope’s list of targets since one of the primary goals of the telescope is to study the origins of life in the Universe. In addition to looking for habitable exoplanets, NASA also wants to study objects within our own Solar System.

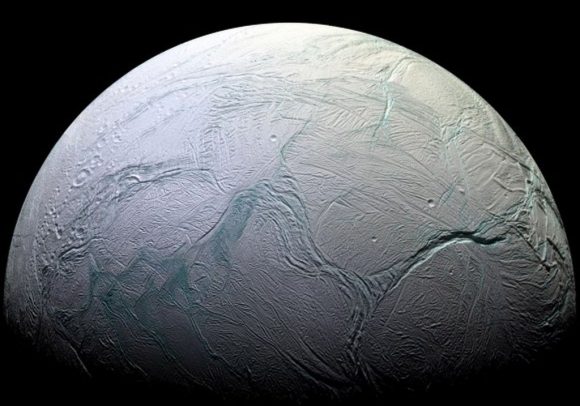

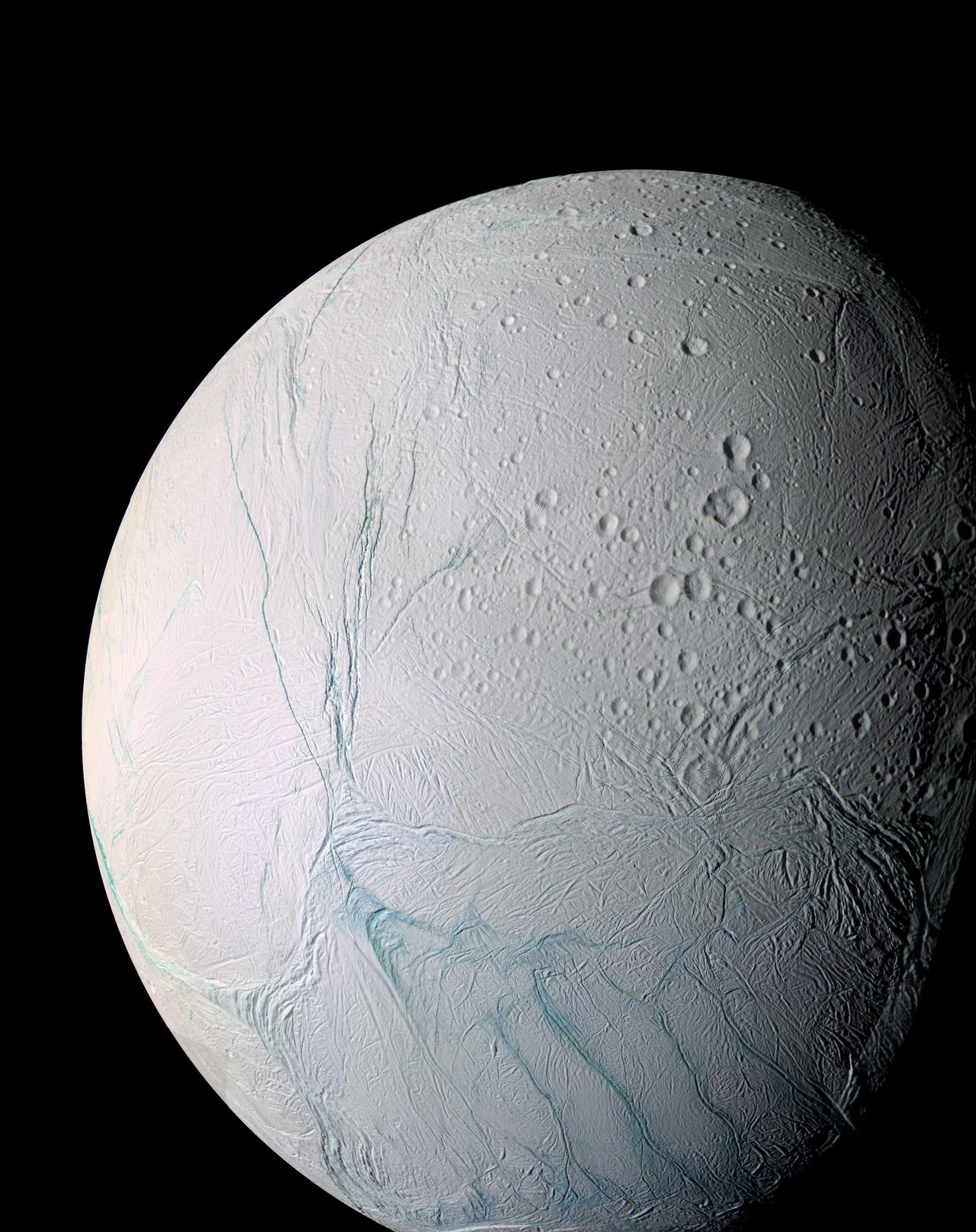

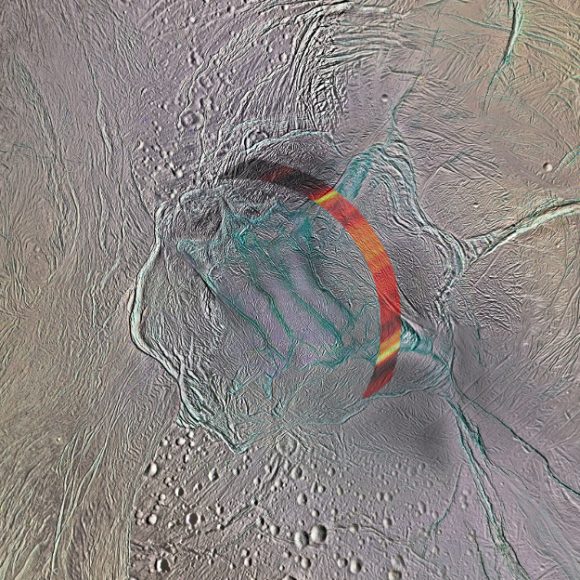

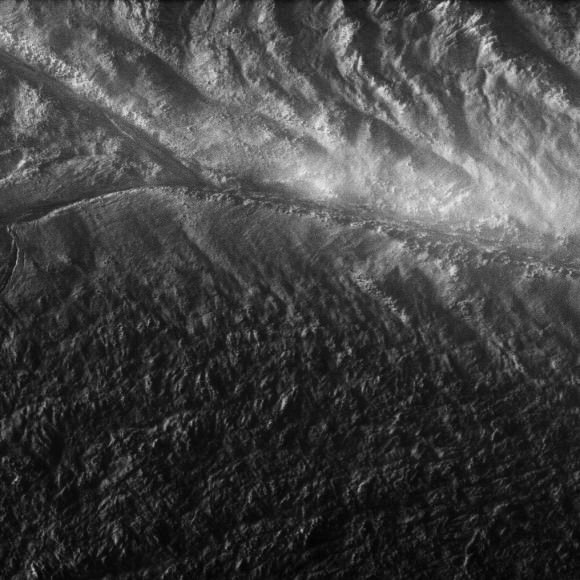

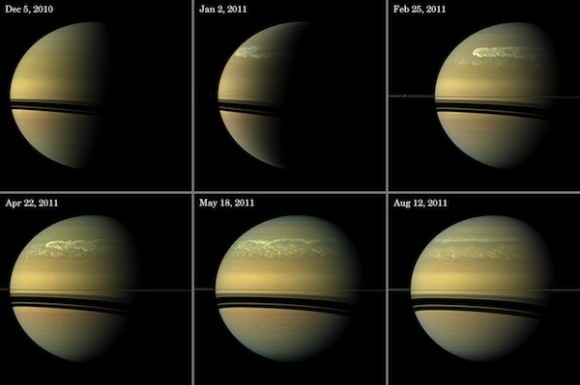

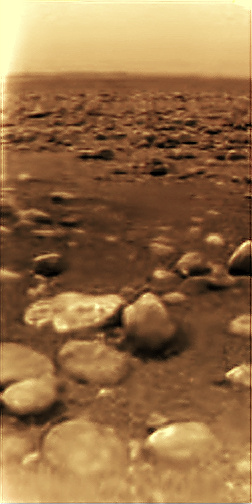

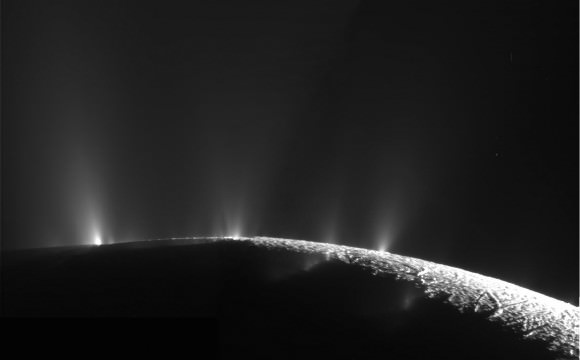

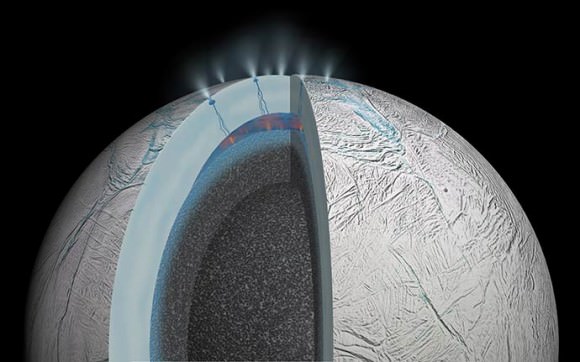

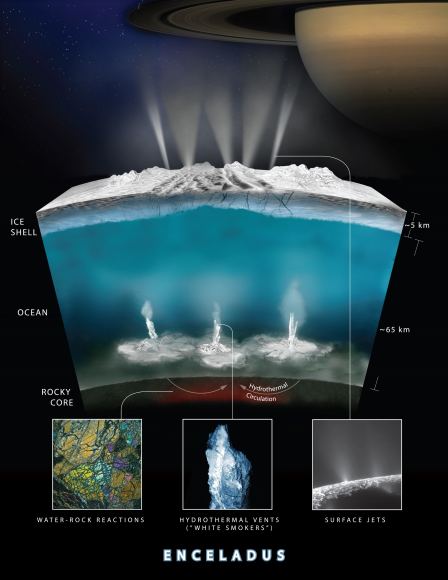

One of the main focuses will be on the plumes of water that have been observed breaking through the icy surfaces of Enceladus and Europa. Since 2005, scientists have known that Enceladus has plumes that periodically erupt from its southern polar region, spewing water and organic chemicals that replenish Saturn’s E-Ring. It has since discovered that these plumes reach all the way into the interior ocean that exists beneath Enceladus’ icy surface.

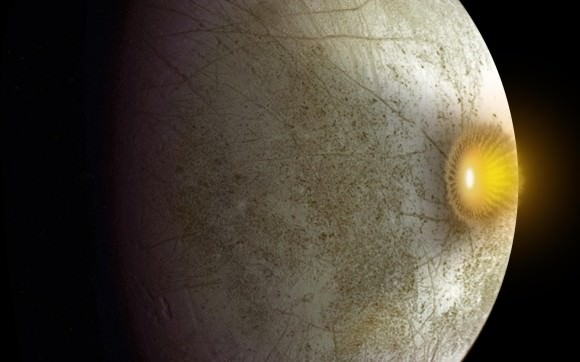

In 2012, astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope detected similar plumes coming from Europa. These plumes were spotted coming from the moon’s southern hemisphere, and were estimated to reach up to 200 km (125 miles) into space. Subsequent studies indicated that these plumes were intermittent, and presumably rained water and organic materials from the interior back onto the surface.

These observations were especially intriguing since they bolstered the case for Europa and Enceladus having interior, warm-water oceans that could harbor life. These oceans are believed to be the result of geological activity in the interior that is caused by tidal flexing. Based on the evidence gathered by the Galileo and Cassini orbiters, scientists have theorized that these surface plumes are the result of these same geological processes.

The presence of this activity could also means that these moons have hydrothermal vents located at their core-mantle boundaries. On Earth, hydrothermal vents (located on the ocean floor) are believed to have played a major role in the emergence of life. As such, their existence on other bodies within the Solar System is viewed as a possible indication of extra-terrestrial life.

The effort to study these “Ocean Worlds” will be led by Geronimo Villanueva, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. As he explained in a recent NASA press statement, he and his team will be addressing certain fundamental questions:

“Are they made of water ice? Is hot water vapor being released? What is the temperature of the active regions and the emitted water? Webb telescope’s measurements will allow us to address these questions with unprecedented accuracy and precision.”

Villanueva’s team is part of a larger effort to study the Solar System, which is being led by Heidi Hammel – the executive VP of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA). As she described the JWST’s “Ocean World” campaign to Universe Today via email:

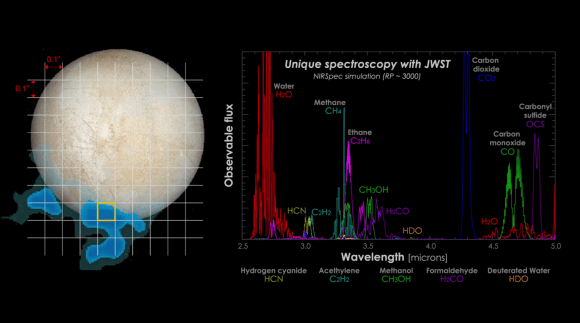

“We will be seeking signatures of plume activity on these ocean worlds as well as active spots. With the near-infrared camera of NIRCAM, we will have just enough spatial resolution to distinguish general regions of the moons that could be “active” (creating plumes). We will also use spectroscopy (examining specific colors of light) to sense the presence of water, methane and several other organic species in plume material.”

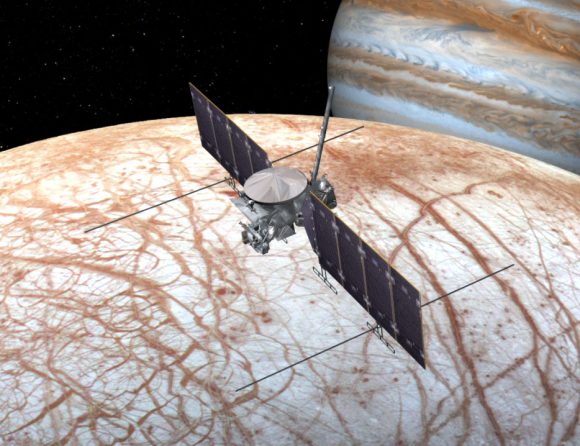

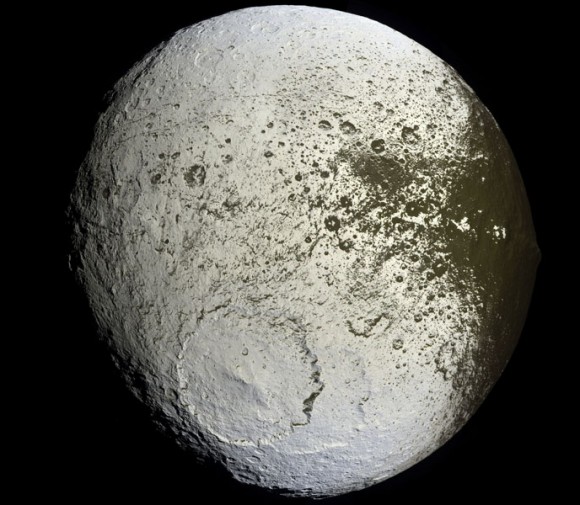

To study Europa, Villanueva and his colleagues will take high-resolution imagery of Europa using the JWST’s near-infrared camera (NIRCam). These will be used to study the moon’s surface and search for hot spots that are indicative of plumes and geological activity. Once a plume is located, the team will determine its composition using Webb’s near-infrared spectrograph (NIRSpec) and mid-infrared instrument (MIRI).

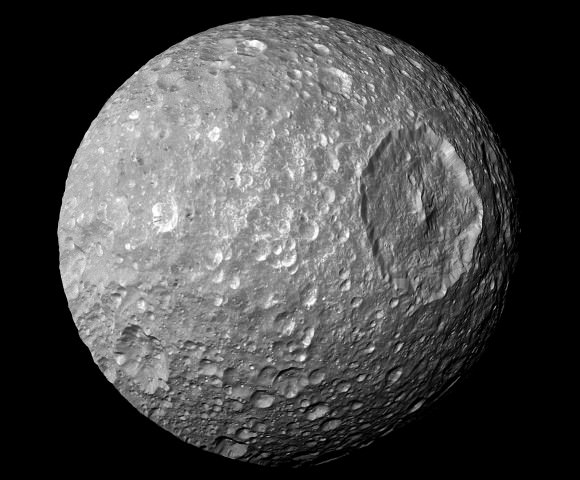

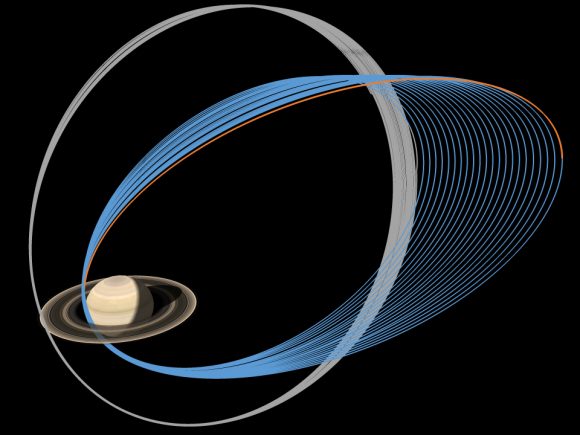

For Enceladus, the team will be analyze the molecular composition of its plumes and perform a broad analysis of its surface features. Due to its small size, high-resolution of the surface will not be possible, but this should not be a problem since the Cassini orbiter already mapped much of its surface terrain. All told, Cassini has spent the past 13 years studying the Saturn system and will conclude the “Grande Finale” phase of its mission this September 15th.

These surveys, it is hoped, will find evidence of organic signatures in the plumes, such as methane, ethanol and ethane. To be fair, there are no guarantees that the JWST’s observations will coincide with plumes coming from these moons, or that the emissions will have enough organic molecules in them to be detectable. Moreover, these indicators could also be caused by geological processes.

Nevertheless, the JWST is sure to provide evidence that will allow scientists to better characterize the active regions of these moons. It is also anticipated that it will be able to pinpoint locations that will be of interest for future missions, such as NASA’s Europa Clipper mission. Consisting of an orbiter and lander, this mission – which is expected to launch sometime in the 2020s – will attempt to determine if Europa is habitable.

As Dr. Hammel explained, the study of these two “Ocean Moons” is also intended to advance our understanding about the origins of life in the Universe:

“These two ocean moons are thought to provide environments that may harbor water-based life as we know it. At this point, the issue of life elsewhere is completely unknown, though there is much speculation. JWST can move us closer to understanding these potentially habitable environments, complementing robotic spacecraft missions that are currently in development (Europa Clipper) and may be planned for the future. At the same time, JWST will be examining the far more distant potentially habitable environments of planets around other stars. These two lines of exploration – local and distant – allow us to make significant advances in the search for life elsewhere.”

Once deployed, the JWST will be the most powerful space telescope ever built, relying on eighteen segmented mirrors and a suite of instruments to study the infrared Universe. While it is not meant to replace the Hubble Space Telescope, it is in many ways the natural heir to this historic mission. And it is certainly expected to expand on many of Hubble’s greatest discoveries, not the least of which are here in the Solar System.

Be sure to check out this video on the kinds of spectrographic data the JWST will provide in the coming years, courtesy of NASA:

Further Reading: NASA