For those people who have had the privilege of jet-setting or traveling the globe, its pretty obvious that the world is a pretty big place. When you consider how long it took for human beings to settle every corner of it (~85,000 years, give or take a decade) and how long it took us to explored and map it all out, terms like “small world” cease to have any meaning.

But to complicate matters a little, the diameter of Earth – i.e. how big it is from one end to the other – varies depending on where you are measuring from. Since the Earth is not a perfect sphere, it has a different diameter when measured around the equator than it does when measured from the poles. So what is the Earth’s diameter, measured one way and then the other?

Oblate Spheroid:

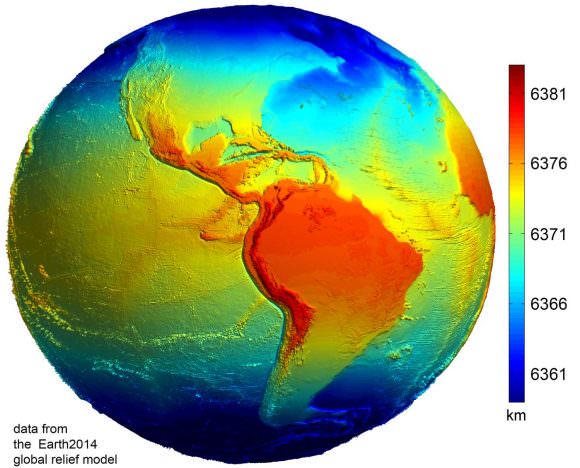

Thanks to improvements made in the field of astronomy by the 17th and 18th centuries – as well as geodesy, a branch of mathematics dealing with the measurement of the Earth – scientists have learned that the Earth is not a perfect sphere. In truth, it is what is known as an “oblate spheroid”, which is a sphere that experiences flattening at the poles.

According to the 2004 Working Group of the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), Earth experiences a flattening of 0.0033528 at the poles. This flattening is due to Earth’s rotational velocity – a rapid 1,674.4 km/h (1,040.4 mph) – which causes the planet to bulge at the equator.

Equatorial vs Polar Diameter:

Because of this, the diameter of the Earth at the equator is about 43 kilometers (27 mi) larger than the pole-to-pole diameter. As a result, the latest measurements indicate that the Earth has an equatorial diameter of 12,756 km (7926 mi), and a polar diameter of 12713.6 km (7899.86 mi).

In short, objects located along the equator are about 21 km further away from the center of the Earth (geocenter) than objects located at the poles. Naturally, there are some deviations in the local topography where objects located away from the equator are closer or father away from the center of the Earth than others in the same region.

The most notable exceptions are the Mariana Trench – the deepest place on Earth, at 10,911 m (35,797 ft) below local sea level – and Mt. Everest, which is 8,848 meters (29,029 ft) above local sea level. However, these two geological features represent a very minor variation when compared to Earth’s overall shape – 0.17% and 0.14% respectively.

Meanwhile, the highest point on Earth is Mt. Chiborazo. The peak of this mountain reaches an attitude of 6,263.47 meters (20,549.54 ft) above sea level. But because it is located just 1° and 28 minutes south of the equator (at the highest point of the planet’s bulge), it receives a natural boost of about 21 km.

Mean Diameter:

Because of the discrepancy between Earth’s polar and equatorial diameter, astronomers and scientists often employ averages. This is what is known as its “mean diameter”, which in Earth’s case is the sum of its polar and equatorial diameters, which is then divided in half. From this, we get a mean diameter of 12,742 km (7917.5 mi).

The difference in Earth’s diameter has often been important when it comes to planning space launches, the orbits of satellites, and when circumnavigating the globe. Given that it takes less time to pass over the Arctic or Antarctica than it does to swing around the equator, sometimes this is the preferred path.

We have written many interesting articles about the Earth and mountains here at Universe Today. Here’s Planet Earth, The Rotation of the Earth, What is the Highest Point on Earth?, and Mountains: How Are They Formed?

Here’s how the diameter of the Earth was first measured, thousands of years ago. And here’s NASA’s Earth Observatory.

We did an episode of Astronomy Cast just on the Earth. Give it a listen, Episode 51: Earth.

Sources: