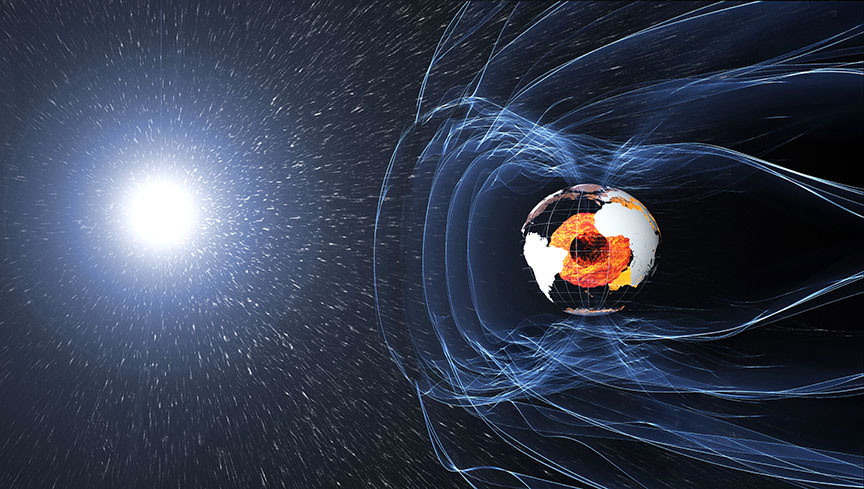

Earth’s magnetic field is one of the most mysterious features of our planet. It is also essential to life as we know it, ensuring that our atmosphere is not stripped away by solar wind and shielding life on Earth from harmful radiation. For some time, scientists have theorized that it is the result of a dynamo action in our core, where the liquid outer core revolves around the solid inner core and in the opposite direction of the Earth’s rotation.

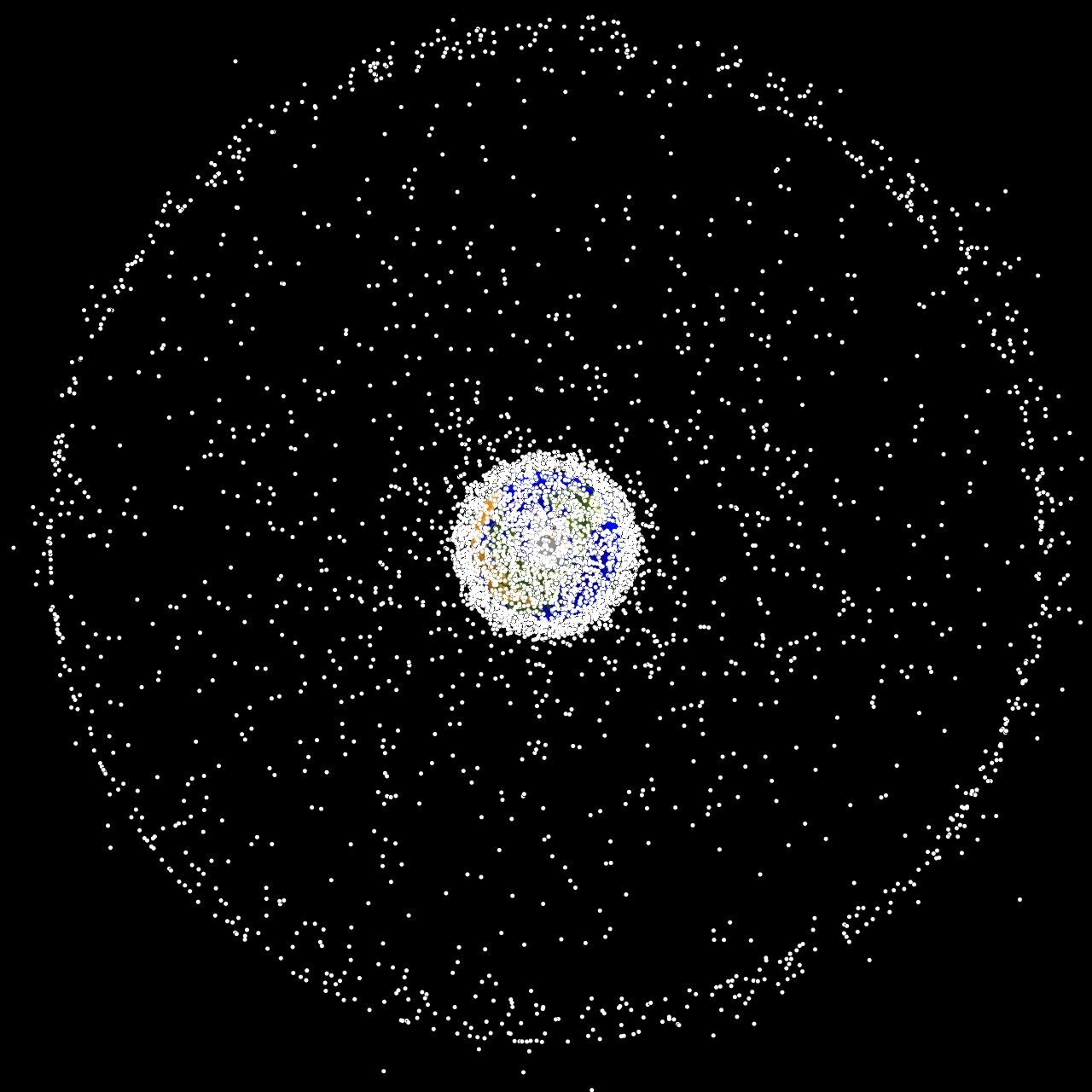

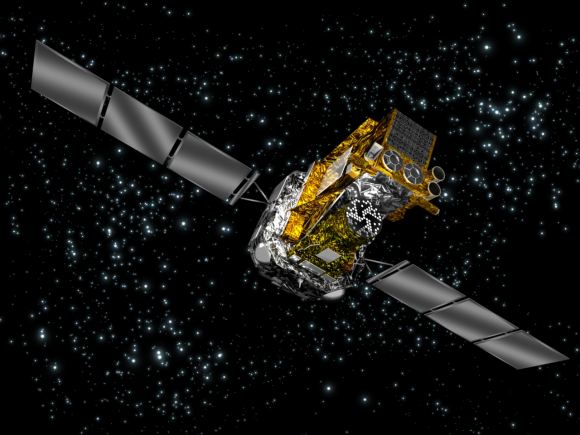

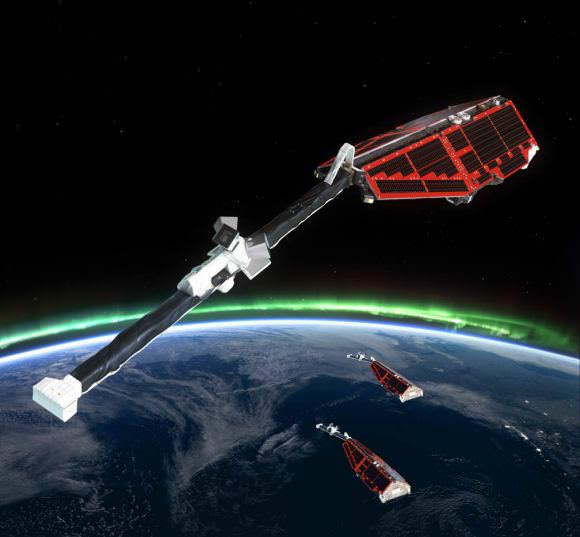

In addition, Earth’s magnetic field is affected by other factors, such as magnetized rocks in the crust and the flow of the ocean. For this reason, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Swarm satellites, which have been continually monitoring Earth’s magnetic field since its deployment, recently began monitoring Earth’s oceans – the first results of which were presented at this year’s European Geosciences Union meeting in Vienna, Austria.

The Swarm mission, which consists of three Earth-observation satellites, was launched in 2013 for the sake of providing high-precision and high-resolution measurements of Earth’s magnetic field. The purpose of this mission is not only to determine how Earth’s magnetic field is generated and changing, but also to allow us to learn more about Earth’s composition and interior processes.

Beyond this, another aim of the mission is to increase our knowledge of atmospheric processes and ocean circulation patterns that affect climate and weather. The ocean is also an important subject of study to the Swarm mission because of the small ways in which it contributes to Earth’s magnetic field. Basically, as the ocean’s salty water flows through Earth’s magnetic field, it generates an electric current that induces a magnetic signal.

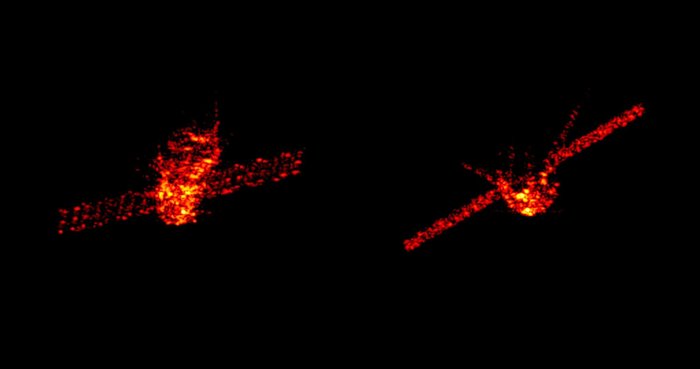

Because this field is so small, it is extremely difficult to measure. However, the Swarm mission has managed to do just that in remarkable detail. These results, which were presented at the EGU 2018 meeting, were turned into an animation (shown below), which shows how the tidal magnetic signal changes over a 24 hour period.

As you can see, the animation shows temperature changes in the Earth’s oceans over the course of the day, shifting from north to south and ranging from deeper depths to shallower, coastal regions. These changes have a minute effect on Earth’s magnetic field, ranging from 2.5 to -2.5 microtesla. As Nils Olsen, from the Technical University of Denmark, explained in a ESA press release:

“We have used Swarm to measure the magnetic signals of tides from the ocean surface to the seabed, which gives us a truly global picture of how the ocean flows at all depths – and this is new. Since oceans absorb heat from the air, tracking how this heat is being distributed and stored, particularly at depth, is important for understanding our changing climate. In addition, because this tidal magnetic signal also induces a weak magnetic response deep under the seabed, these results will be used to learn more about the electrical properties of Earth’s lithosphere and upper mantle.”

By learning more about Earth’s magnetic field, scientists will able to learn more about Earth’s internal processes, which are essential to life as we know it. This, in turn, will allow us to learn more about the kinds of geological processes that have shaped other planets, as well as determining what other planets could be capable of supporting life.

Be sure to check out this comic that explains how the Swarm mission works, courtesy of the ESA.

Further Reading: ESA