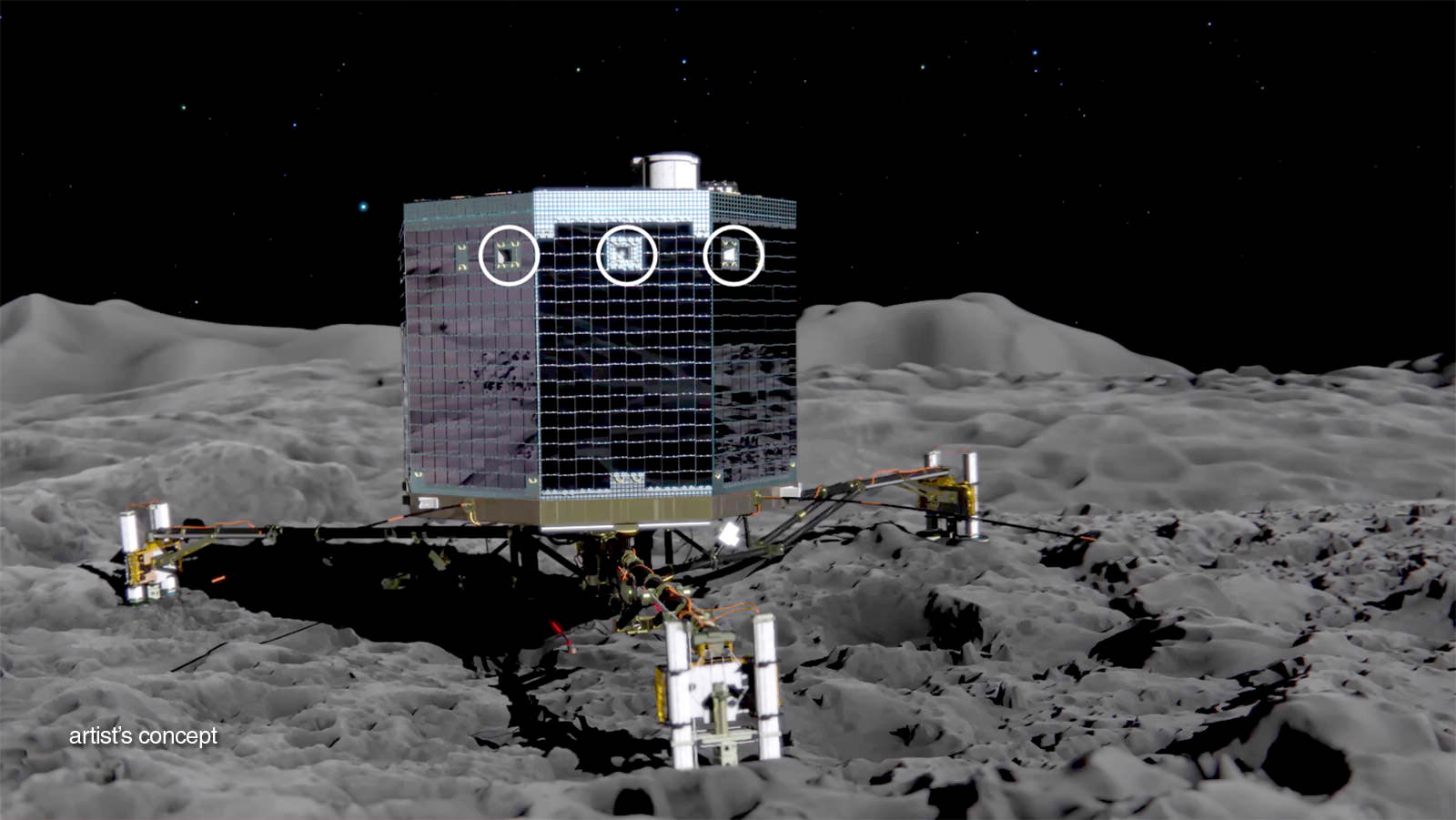

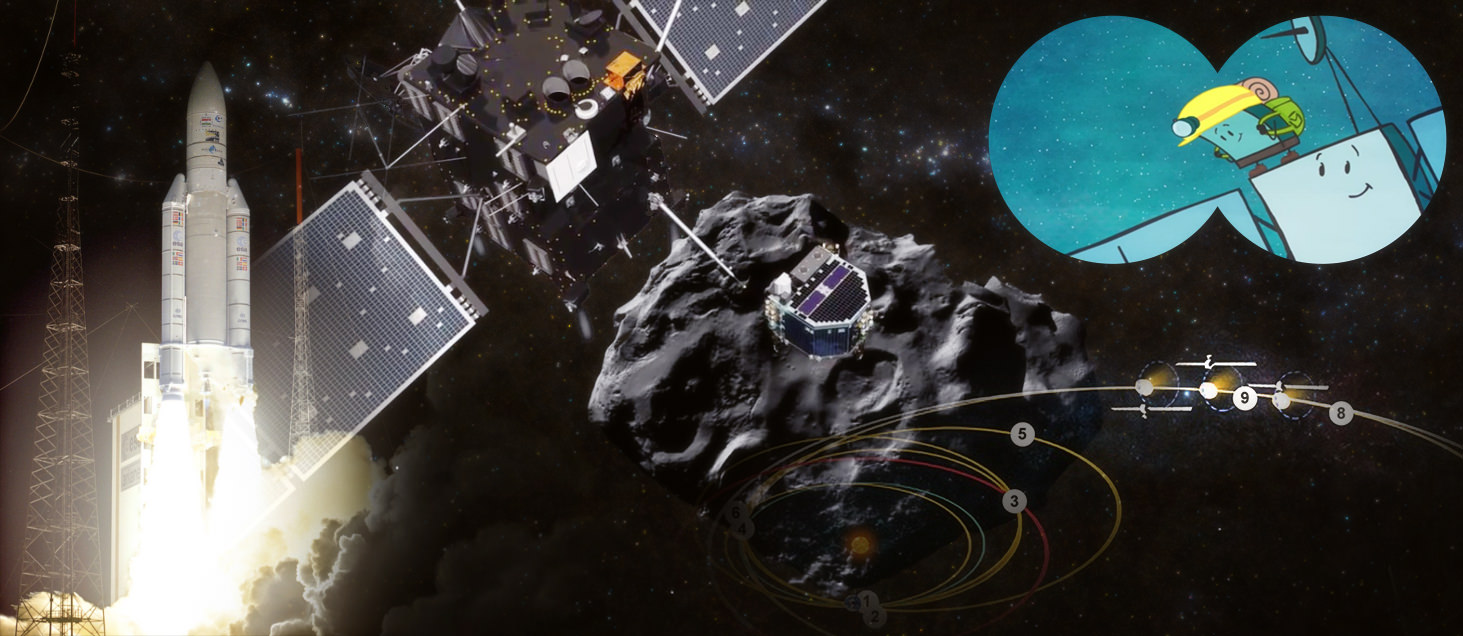

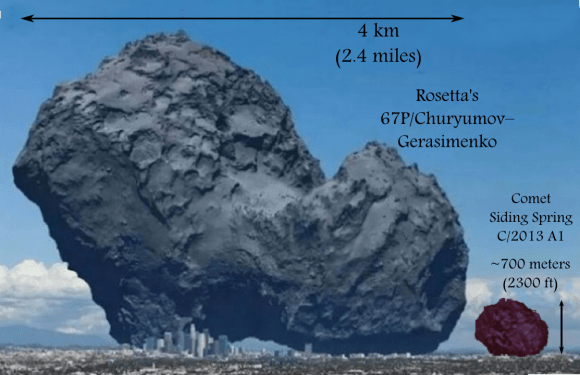

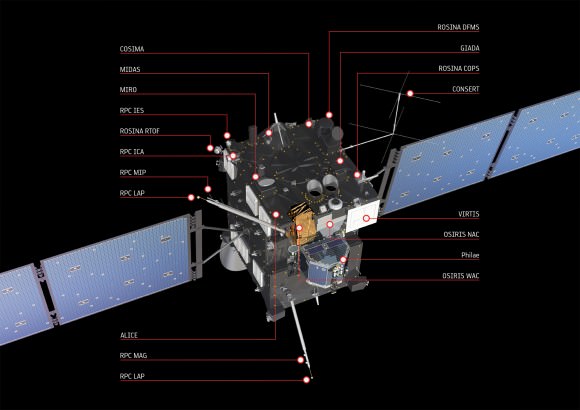

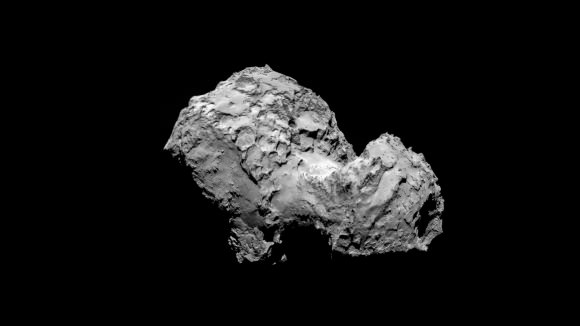

This week, history was made as the Rosetta mission’s Philae lander touched down on the surface of 67P/Churnyumov-Gerasimenko. Days before this momentous event took place, the science team presented some staggering pictures of the comet at a planetary conference in Tucson, Arizona, where guests were treated to the first color images taken by the spacecraft’s high-resolution camera.

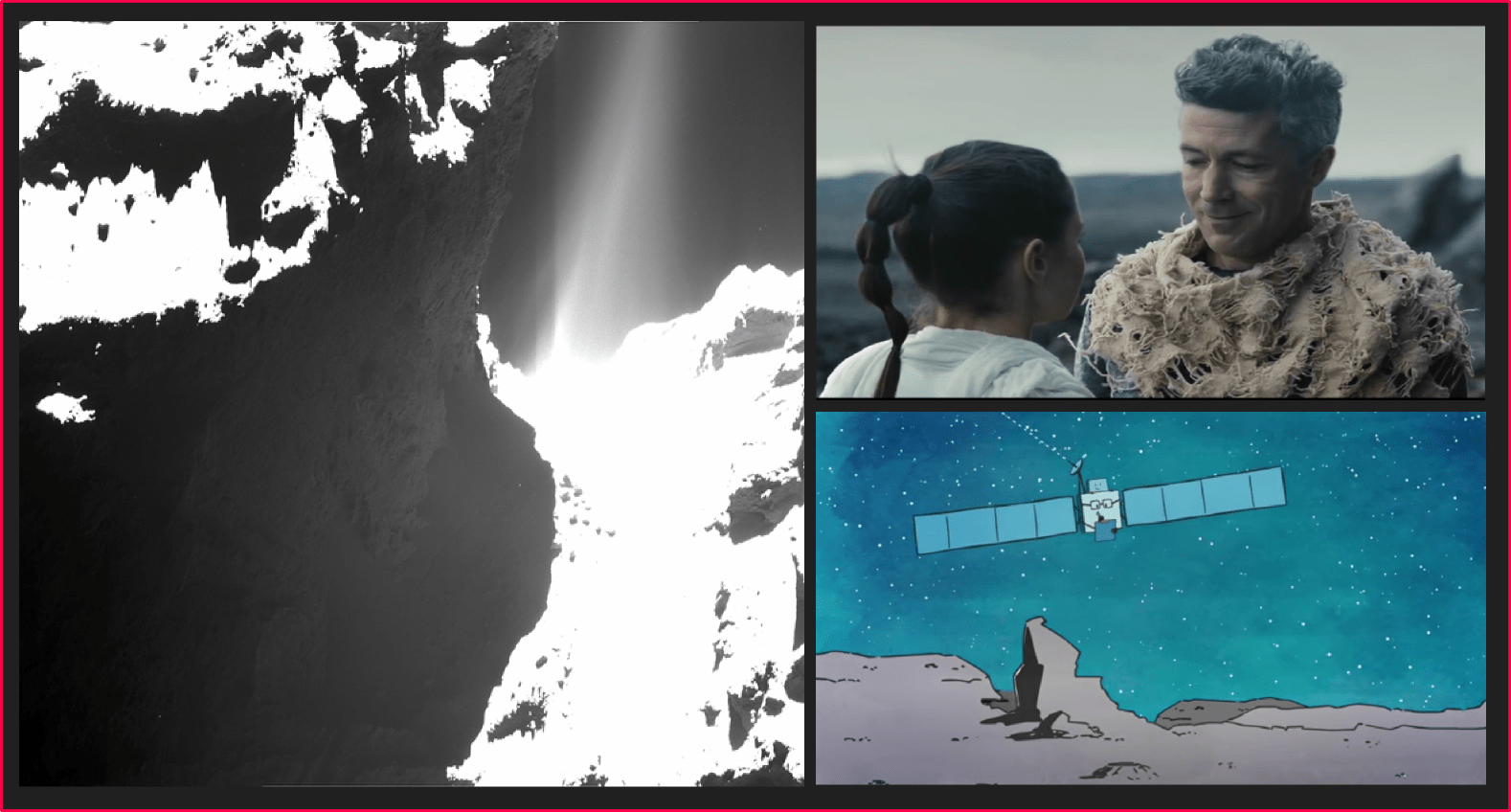

Unfortunately for millions of space enthusiasts around the world, none of these exciting images were released to the public. In addition, much of the images taken of the comet over the past few months as Rosetta closed in on it have similarly not been released. This has led to demands for more openness, which in turn has focused attention on ESA’s image and data release policy.

Allowing scientists to withhold data for some period of time is not uncommon in planetary science. According to Jim Green, the director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, a 6-month grace period is typical for principal investigator-led spacecraft. However, NASA headquarters can also insist that the principal investigator release data for key media events.

This has certainly been the case where the Curiosity and other Mars rover missions were concerned, not to mention the Cassini-Huygens mission. On many occasions, NASA chose to release images to the public almost immediately after they were obtained.

However, ESA has a different structure than NASA. It relies much more on contributions from member-states, whereas NASA pays for most of its instruments directly. Rosetta’s main mission camera – the Optical, Spectroscopic, and Infrared Remote Imaging System (OSIRIS) – was developed by a consortium of institutes led by the Max-Planck-Institute for Solar System Research. As a result, ESA has less control over how information obtained by this specific camera is disseminated.

Journalist Eric Hand recently covered this imagery release dilemma in an article in Science, revealing that even scientists at Darmstadt, Germany this week — the location of ESA’s mission control for Philae’s landing — had not seen the science images that were being shared at the Planetary Science conference. Project scientist Matt Taylor was reduced to learning about the new results by looking at Twitter feeds on his phone.

Hand quoted Taylor as saying the decision when to publicly release images is a “tightrope” walk. And Hand also said some “ESA officials are worried that the principal investigators for the spacecraft’s 11 instruments are not releasing enough information, and many members of the international community feel the same way.”

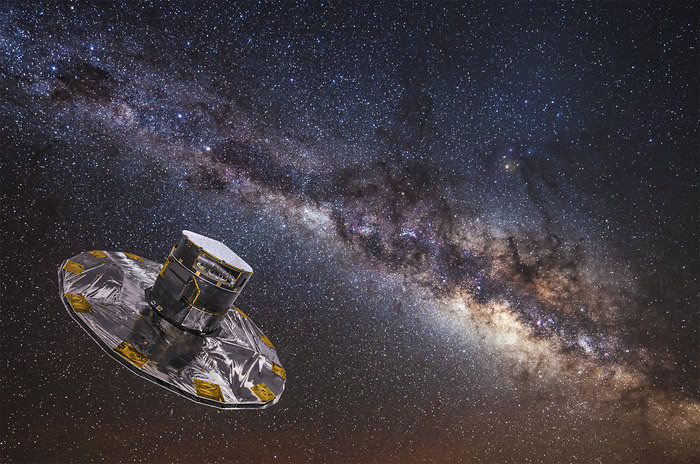

Back in July, ESA responded to these calls for more information with a press release, in which they claimed that an “open-data” policy is not the norm for either ESA or NASA. Responding to the examples of the Mars rovers and Cassini-Huygens, which have been cited by critics for more openness, ESA countered with the Hubble Space Telescope, the Chandra X-Ray observatory, the MESSENGER mission to Mercury, and even some NASA Mars orbiters.

In these cases, they claimed, the data obtained was subject to a “proprietary period”, which also pertains to data from ESA’s Mars Express, XMM-Newton, and Rosetta missions. This period, they said, is typically 6-12 months, and “gives exclusive access to the scientists who built the instruments or to scientists who made a winning proposal to make certain observations.”

Nevertheless, there is still some criticism by those who think that releasing more images would be a positive gesture and not compromise any ESA scientist’s ability to conduct research.

As space blogger Daniel Fischer said in response to the ESA press release, “Who is writing scientific papers already about the distant nucleus that is just turning into a shape? And on the weekly schedule a sampling of these images is coming out anyway, with a few days delay… Presenting the approach images, say, one per day and with only hours delay would thus not endanger any priorities but instead give the eager public a unique chance to ‘join the ride’, just as they can with Cassini or the Mars rovers.”

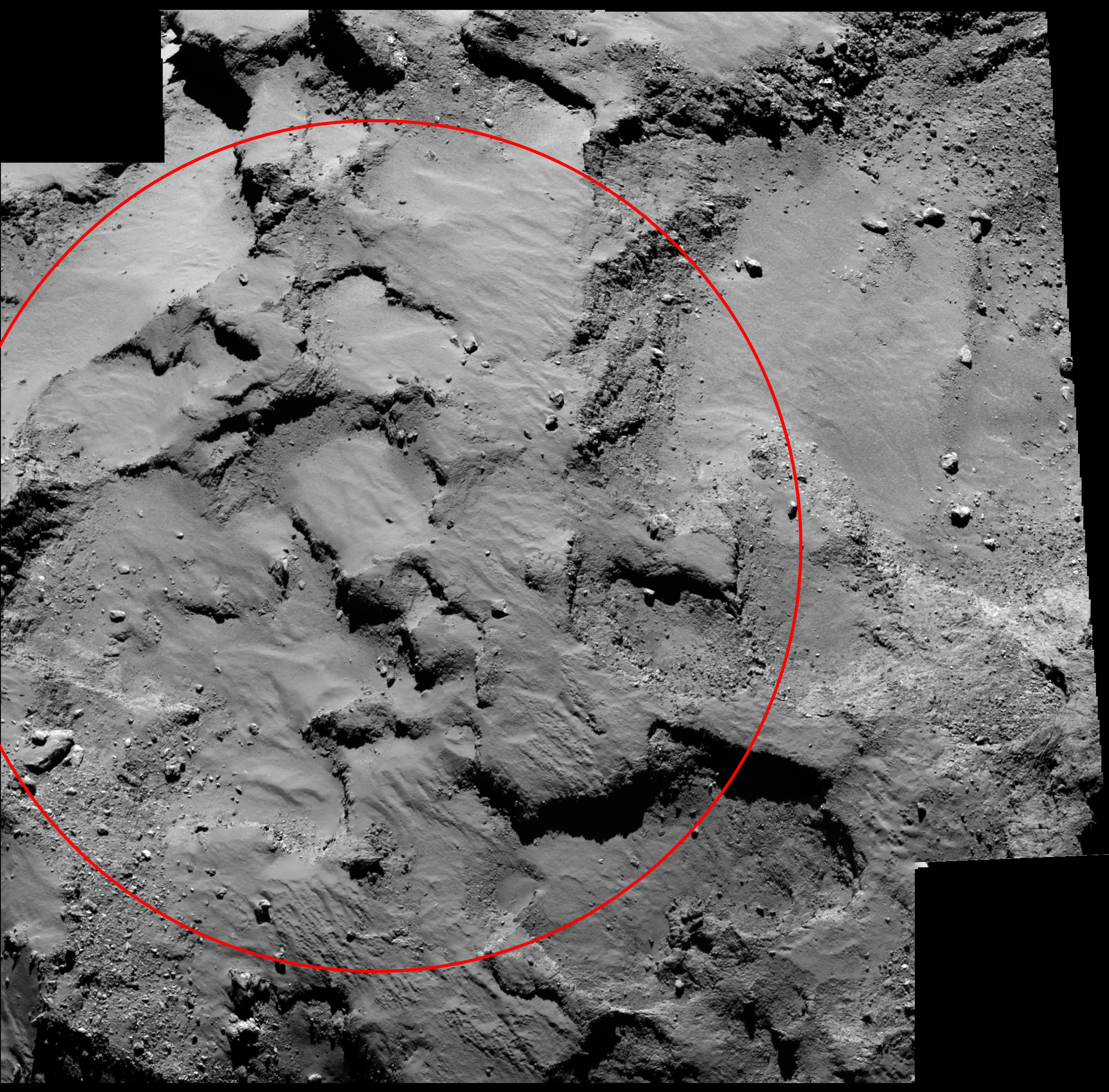

In particular, a lot of criticism has been focused on the OSIRIS camera team, led by principal investigator Holger Sierks. Days before the Philae Lander put down on the comet, an amateur astronomer, space educator and image processor – wrote the following on his space blog Cumbrian Sky:

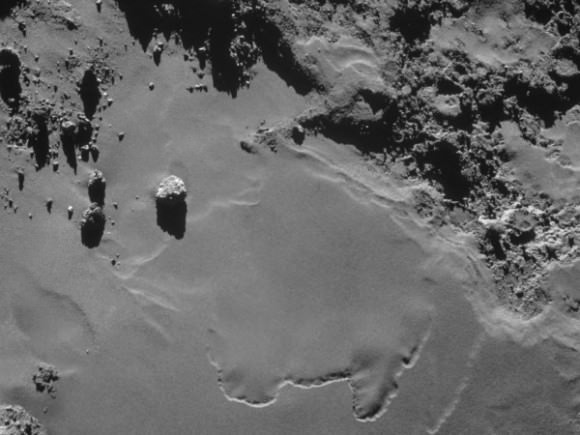

[The OSIRIS team’s] attitude towards the public, the media, and ESA itself has been one of arrogant contempt, and I have no doubt at all that their selfish behaviour has damaged the mission and the reputation and public image ESA. Their initial arguments that they had to keep images back to allow them to do their research no longer hold up now. They must have taken many hundreds of jaw droppingly detailed images by now, the images everyone has been looking forward to ever since ROSETTA launched a decade ago, so could easily release dozens of images which pose no risk to their work or careers, but they have released only a handful, and those have been the least-detailed, least-remarkable images they could find.

However, in Hand’s Science article, Sierks said that he feels the OSIRIS team has already provided a fair amount of data to the public. Currently, about one image is released a week – a rate that seems to Sierks to be more than adequate given that they are superior to anything before seen in terms of comet research.

Furthermore, Sierks claimed that other researchers, unaffiliated with the Rosetta team, have submitted papers based on these released images, while his team has been consumed with the daily task of planning the mission. After working on OSIRIS since 1997, Sierks feels that his team should get the first shot at using the data.

This echoes ESA’s July press release, which expressed support for their science teams to have first-crack any data obtained by their instruments. “Because no-one has ever been to 67P/C-G before,” it stated, “each new piece of data from Rosetta has the potential for a scientific discovery. It’s only fair that the instrument science teams have the first chance to make and assess those discoveries.”

The same press release also defended ESA’s decision not to release information from the navigation cameras more freely – which they do have control over. Citing overlap, they indicated that they want to “avoid undermining the priority of the OSIRIS team.”

Prior to Rosetta’s launch in 2004, an embargo of 6 months was set for all the instrument teams. ESA scientists have pointed out that mission documents also stipulate that instrument teams provide “adequate support” to ESA management in its communication efforts.

Mark McCaughrean, an ESA senior science adviser at ESTEC, is one official that believes these support requirements are not being met. He was quoted by Eric Hand in Science as saying, “I believe that [the OSIRIS camera team’s support] has by no means been adequate, and they believe it has,” he says. “But they hold the images, and it’s a completely asymmetric relationship.”

Luckily, ESA has released images of the surface of 67P and what it looked like for the Philae Lander and as it made its descent towards the comet. Additionally, stunning imagery from Rosetta’s navigation camera were recently released. In the coming days and weeks, we can certainly hope that plenty of more interesting images and exciting finds will be coming, courtesy of the Rosetta mission and its many contributors.

Further Reading: Science Mag, NASA, ESA