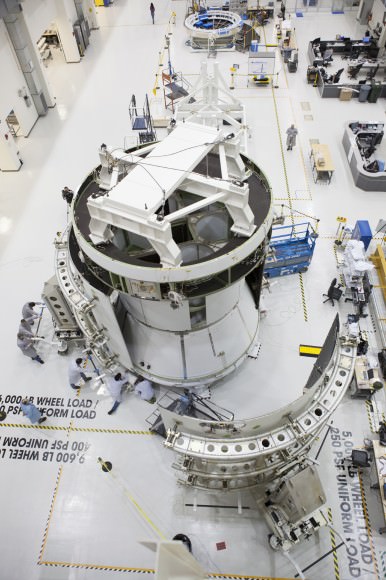

Engineers prepare Orion’s service module for installation of the fairings that will protect it during launch this fall when Orion launches on its first mission. The service module, along with its fairings, is now complete. Credit: NASA

Story Updated[/caption]

2014 is the Year of Orion.

Orion is NASA’s next human spaceflight vehicle destined for astronaut voyages beyond Earth and will launch for the first time later this year on its inaugural test flight from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

The space agency is rapidly pressing forward with efforts to finish building the Orion crew module slated for lift off this Fall on the unmanned Exploration Flight Test – 1 (EFT-1) mission.

NASA announced today that construction of the service module section is now complete.

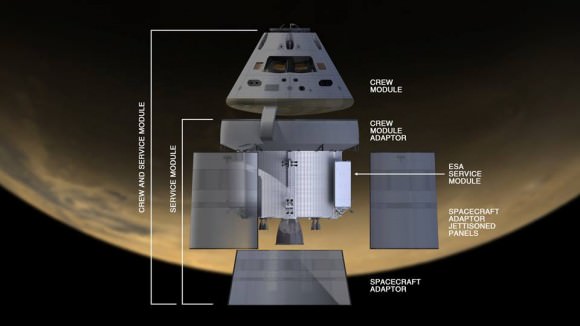

The Orion module stack is comprised of three main elements – the Launch Abort System (LAS) on top, the crew module (CM) in the middle and the service module (SM) on the bottom.

With the completion of the service module, two thirds of the Orion EFT-1 mission stack are now compete.

LAS assembly was finalized in December.

The crew module is in the final stages of construction and completion is due by early spring.

Orion is being manufactured at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) inside a specially renovated high bay in the Operations and Checkout Building (O&C).

“We are making steady progress towards the launch in the fall,” said NASA Administrator Charles Bolden at a media briefing back dropped by the Orion service module inside the O&C facility.

“It’s very exciting because it signals we are almost there getting back to deep space and going much more distant than where we are operating in low Earth orbit at the ISS.”

“And I’m very excited for the young people who will have an opportunity to fly Orion,” Bolden told me in the O&C.

Lockheed Martin is the prime contractor for Orion under terms of a contract from NASA.

Orion is NASA’s first spaceship designed to carry human crews on long duration flights to deep space destinations beyond low Earth orbit, such as asteroids, the Moon, Mars and beyond.

The inaugural flight of Orion on the unmanned Exploration Flight Test – 1 (EFT-1) mission is on schedule to blast off from the Florida Space Coast in mid September 2014 atop a Delta 4 Heavy booster, Scott Wilson, NASA’s Orion Manager of Production Operations at KSC, told Universe Today during a recent interview at KSC.

Orion is currently under development as NASA’s next generation human rated vehicle to replace the now retired space shuttle.

Concurrently, NASA’s commercial crew initiative is fostering the development of commercial space taxi’s to ferry US astronauts to low Earth orbit and the International Space Station (ISS).

Get the details in my interview with SpaceX CEO Elon Musk about his firm’s Dragon ‘space taxi’ launching aboard the SpaceX upgraded Falcon 9 booster – here.

The two-orbit, four- hour EFT-1 flight will lift the Orion spacecraft and its attached second stage to an orbital altitude of 3,600 miles, about 15 times higher than the International Space Station (ISS) – and farther than any human spacecraft has journeyed in 40 years.

The crew module rests atop the service module, similar to the Apollo Moon landing program architecture.

The SM provides in-space power, propulsion capability, attitude control, thermal control, water and air for the astronauts.

For the EFT-1 flight, the SM is not fully outfitted. It is a structural representation simulating the exact size and mass.

In a significant difference from Apollo, Orion is equipped with a trio of massive fairings that encase the SM and support half the weight of the crew module and the launch abort system during launch and ascent. The purpose is to improve performance by saving weight from the service module, thus maximizing the vehicles size and capability in space.

All three fairings are jettisoned at an altitude of 100 miles up when they are no longer need to support the stack.

On the next Orion flight in 2017, the service module will be manufactured built by the European Space Agency (ESA).

“When we go to deep space we are not going alone. It will be a true international effort including the European Space Agency to build the service module,” said Bolden.

The new SM will be based on components from ESA’s Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) which is an unmanned resupply spacecraft used to deliver cargo to the ISS.

A key upcoming activity for the CM is installation of the thermal protection system, including the heat shield.

The heat shield is the largest one ever built. It arrived at KSC last month loaded inside NASA’s Super Guppy aircraft while I observed. Read my story – here.

The 2014 EFT-1 test flight was only enabled by the extremely busy and productive year of work in 2013 by the Orion EFT-1 team.

“There were many significant Orion assembly events ongoing on 2013” said Larry Price, Orion deputy program manager at Lockheed Martin, in an interview with Universe Today at Lockheed Martin Space Systems in Denver.

“This includes the heat shield construction and attachment, power on, installing the plumbing for the environmental and reaction control system, completely outfitting the crew module, attached the tiles and building the service module which finally leads to mating the crew and service modules (CM & SM) in early 2014,” Price told me.

Orion was originally planned to send American astronauts back to Moon – until Project Constellation was cancelled by the Obama Administration.

Now with Orion moving forward and China’s Yutu rover trundling spectacularly across the Moon, one question is which country will next land humans on the Moon – America or China?

Read my story about China’s manned Moon landing plans – here.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Orion, Chang’e-3, Orbital Sciences, SpaceX, commercial space, LADEE, Mars and more news.