The European Space Agency (ESA) was founded by 10 European states back in 1975 with the idea that “We can do more, together.” Today Europe’s gateway to space is a cooperative, intergovernmental organisation, with 20 European member nations representing 500 million citizens, coming together in their national interest and common good. On 20-21 November ESA’s space ministers are meeting in Naples to decide the Agency’s future course. Continue reading “Space for the Cost of a Movie Ticket”

Huge New ESA Tracking Station is Ready for Duty

Caption: ESA’s giant Malargüe tracking station Credits: ESA/S. Marti

To keep in contact with an ever growing armada of spacecraft ESA has developed a tracking station network called ESTRACK. This is a worldwide system of ground stations providing links between satellites in orbit and ESA’s Operations Control Centre (ESOC) located in Darmstadt, Germany. The core ESTRACK network comprises 10 stations in seven countries. Major construction has now been completed on the final piece of this cosmic jigsaw, one of the world’s most sophisticated satellite tracking stations at Malargüe, Argentina, 1000 km west of Buenos Aires.

ESA’s Core Network comprises 10 ESTRACK stations: Kourou (French Guiana), Maspalomas, Villafranca (Spain), Redu (Belgium), Santa Maria (Portugal), Kiruna (Sweden), Perth (Australia) which host 5.5-, 13-, 13.5- or 15-metre antennas. The new tracking station (DSA3) at Malargüe in Argentina, joins two other 35-metre deep-space antennas at New Norcia (DSA1) in Australia (completed in 2002) and Cebreros (DSA2) in Spain, (completed in 2005) to form the European Deep Space Network.

The essential task of ESTRACK stations is to communicate with missions, up-linking commands and down-linking scientific data and spacecraft status information. The tracking stations also gather radiometric data to tell mission controllers the location, trajectory and velocity of their spacecraft, to search for and acquire newly launched spacecraft, in addition to auto-tracking, frequency and timing control using atomic clocks and gathering atmospheric and weather data.

Deep-space missions can be over 2 million kilometres away from the Earth. Communicating at such distances requires highly accurate mechanical pointing and calibration systems. The 35m stations provide the improved range, radio technology and data rates required to send commands, receive data and perform radiometric measurements for current and next-generation exploratory missions such as Mars Express, Venus Express, Rosetta, Herschel, Planck, Gaia, BepiColombo, ExoMars, Solar Orbiter and Juice.

DSA3 is located at 1500m altitude in the clear Argentinian desert air, this and ultra-low-temperature amplifiers installed at the station, have meant that performance has exceeded expectations. The first test signals were received in June 2012 from Mars Express, over a distance of about 193 million km, proving that the station’s technology is ready for duty.

“Initial in-service testing with the Malargüe station shows excellent results.” “Our initial in-service testing with the Malargüe station shows excellent results,” says Roberto Maddè, ESA’s project manager for DSA 3 construction. “We have been able to quickly and accurately acquire signals from ESA and NASA spacecraft, and our station is performing better than specified.”

All three tracking stations are also equipped for radio science, which studies how matter, such as planetary atmospheres, affects the radio waves as they pass through. This can provide important information on the atmospheric composition of Mars, Venus or the Sun.

The tracking capability of all three ESA deep space stations also work in cooperation with partner agencies such as NASA and Japan’s JAXA, helping to boost science data return for all. The three Deep Space Antenna can be linked to the 7 stations comprising the Core Network as well as five other stations making up the larger Augmented Network and eleven additional stations that make up a global Cooperative Network with other space agencies from around the world.

Now that major construction is complete, teams are preparing DSA 3 for hand-over to operations, formal inauguration late this year and entry in routine service early in 2013.

Find out more about Malargüe and the Deep Space Antenna here and the other ESTRACK tracking stations here

Stirred, Not Shaken. Black Hole Antics Puff Up Whopper of a Galaxy

Its massive gravitational field warping space, the huge elliptical galaxy A2261-BCG, seems to have a diffuse halo of stars instead of a bright central galactic core. Image credit: NASA/ESA Hubble

Bloated far beyond the size of normal galaxies, one or more black holes may have puffed up an elliptical galaxy to a whopping size, according to astronomers. To their surprise, however, the black holes are missing.

Normally, scientists measure a concentrated peak of light surrounding the central black hole surrounded by a fuzzy halo of stars. Instead, astronomers, using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, find that the galaxy, known as A2261-BCG, is just a diffuse, bloated foggy patch of light. The intensity of starlight remains even across the entire galaxy. Past Hubble observations show supermassive black holes, each weighing billions of times more than our Sun, reside at the cores of nearly all galaxies.

“Expecting to find a black hole in every galaxy is sort of like expecting to find a pit inside a peach,” explained astronomer and co-author Tod Lauer in a press release. Lauer is with the National Optical Astronomy Observatory in Tucson, Ariz. “With this Hubble observation, we cut into the biggest peach and we can’t find the pit. We don’t know for sure that the black hole is not there, but Hubble shows that there’s no concentration of stars in the core.”

So where are the black holes?

Astronomers, in a paper that appeared in the September 10 issue of The Astrophysical Journal, have two ideas, both involving galactic billiards, for the galaxy’s puffy appearance. In one scenario, a pair of merging black holes gravitationally stir up then scatter the galaxy’s stars. In another, the merging black holes are ejected leaving the swarm of stars with no gravitational anchor allowing them to wander outward.

Galaxy cores tend to be sized proportionally to the wheeling expanse of the host galaxy. In the case of A2261-BCG, which spans about a million light-years (10 times that of our Milky Way Galaxy), the central region is three times larger than other very luminous galaxies, according to the paper. The monster galaxy is the most massive and brightest galaxy in the Abell 2261 galaxy cluster.

Team leader Marc Postman of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Md., said in the press release that the galaxy stood out in the Hubble image. “When I first saw the image of this galaxy, I knew right away it was unusual,” Postman explained. “The core was very diffuse and very large. The challenge was then to make sense of all the data, given what we knew from previous Hubble observations, and come up with a plausible explanation for the intriguing nature of this particular galaxy.”

The team admits the ejected black-hole ideas sound far-fetched, “but that’s what makes observing the universe so intriguing — sometimes you find the unexpected,” said Postman.

As a follow-up, the team is searching for the sound of material falling into the black hole using the Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope in New Mexico. Comparing the VLA data with Hubble images will allow the researchers to confirm the existence of a black hole and map its location.

Source: Hubblesite

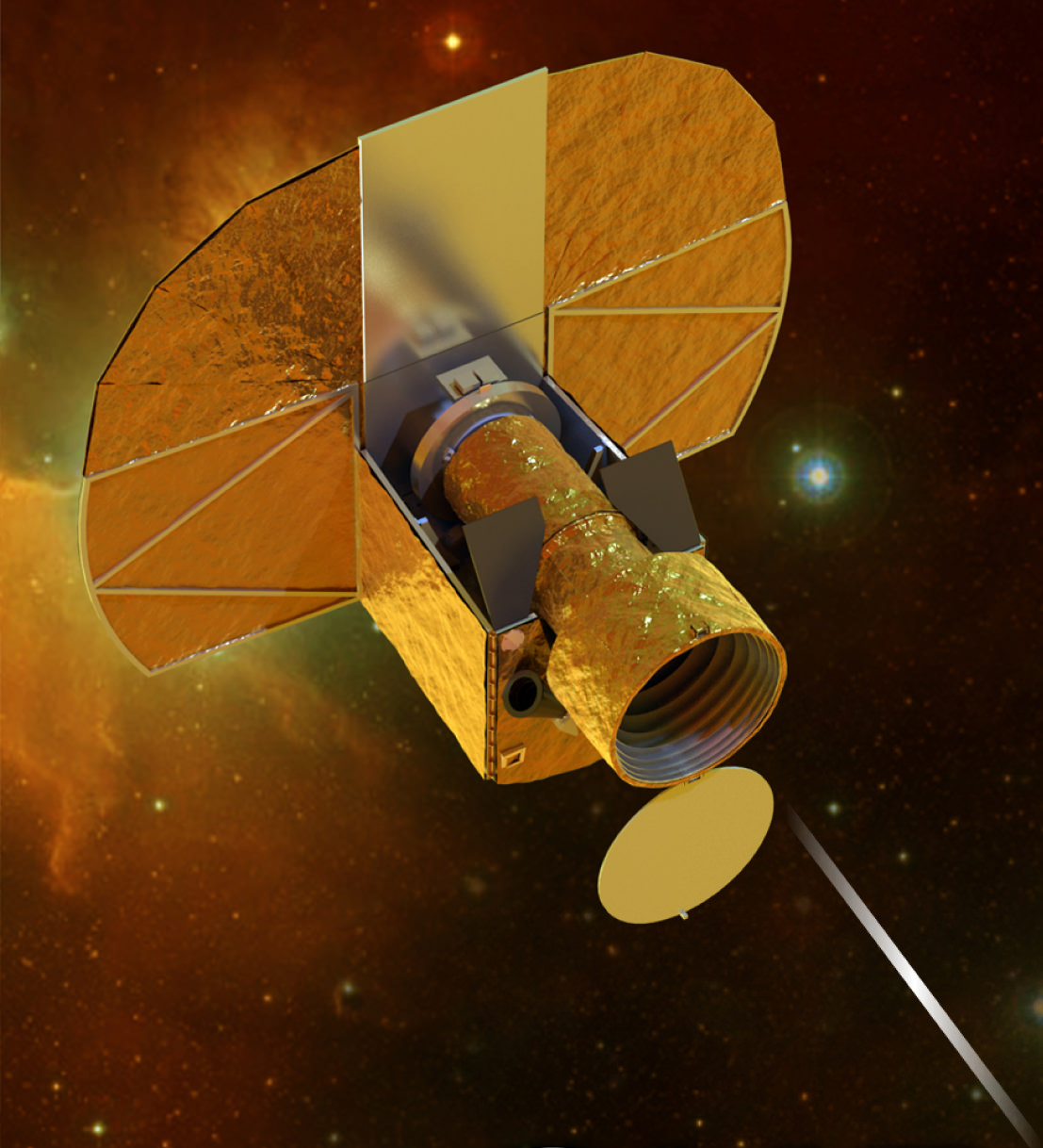

Cheops – A Little Satellite with Big Ideas

Caption: Artist impression of Cheops. Credit: University of Bern

Big isn’t always better. This is certainly true at ESA’s new Science Programme. They are looking to low cost, small scale missions that can be rapidly developed, in order to offer greater flexibility in response to new ideas from the scientific community, to complement the broader Medium- and Large-class missions. Back in March ESA called for ideas for dedicated, quick-turnaround missions focusing on key issues in space science. From 26 proposals submitted, ESA has now approved a new mission to be launched in 2017. Though small in scale this mission is big on ambition: to search for nearby habitable planets.

Cheops stands for CHaracterising ExOPlanets Satellite. It has a planned mission lifetime of 3.5 years during which it will operate in a Sun-synchronous low-Earth orbit at an altitude of 800 km, free from distortion by Earth’s atmosphere. It will target nearby, bright stars already known to have planets orbiting around them.

By high-precision monitoring of the star’s brightness, Cheops will search for signs of a ‘transit’ as a planet passes across the star’s face, it will also be able to look for smaller planets, impossible to see using ground based telescopes, around those stars.

While NASA’s Kepler mission has confirmed 77 planets so far, with another 2,321 candidate planets, not one is close enough to Earth to be analysed in detail. Cheops on the other hand, will be able to take accurate measurements of the radius of the planet. For those planets with a known mass, this will reveal the planet’s density and provide an indication of the internal structure. It will help scientists understand the formation of planets from ‘super-Earths’, a few times the mass of the Earth, up to Neptune-sized worlds. It will also identify planets with significant atmospheres which can then be analysed for signs of life by ground-based telescopes, and the next generation of space telescopes now being built, such as the ground-based European Extremely Large Telescope and the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope.

“By concentrating on specific known exoplanet host stars, Cheops will enable scientists to conduct comparative studies of planets down to the mass of Earth with a precision that simply cannot be achieved from the ground,” said Professor Alvaro Giménez-Cañete, ESA Director of Science and Robotic Exploration.

The plan is for Cheops to be the first of a series of similar small missions, that can be rapidly developed at low cost to investigate new scientific ideas quickly. Cheops will be developed as a partnership between ESA and Switzerland, with a number of other ESA Member States delivering substantial contributions.

Find out more about Cheops here

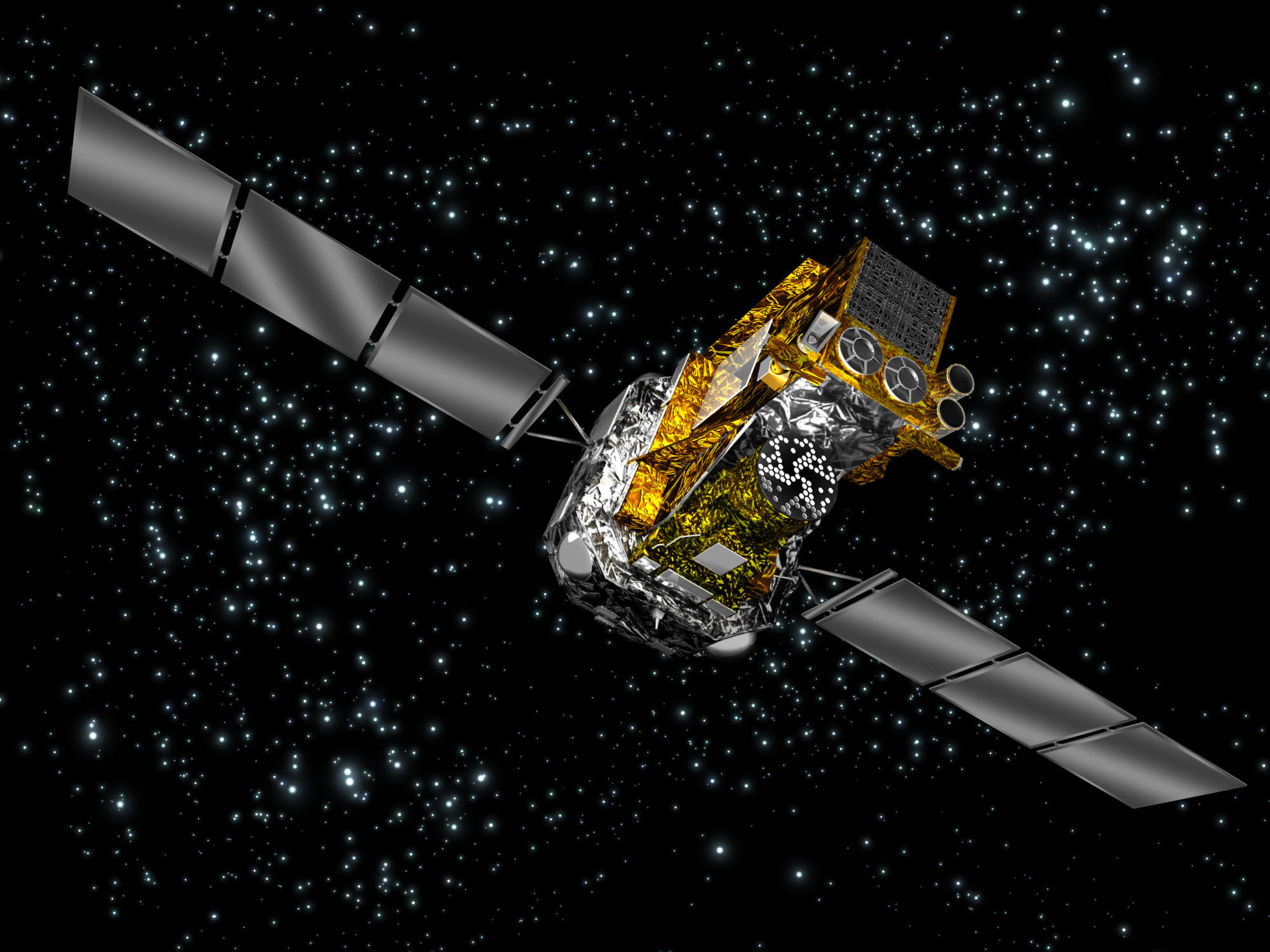

Integral: Ten Years Tracking Extreme Radiation Across the Universe

Caption: Artist’s impression of ESA’s orbiting gamma-ray observatory Integral. Image credit: ESA

Integral, ESA’s International Gamma-Ray Astrophysics Laboratory launched ten years ago this week. This is a good time to look back at some of the highlights of the mission’s first decade and forward to its future, to study at the details of the most sensitive, accurate, and advanced gamma-ray observatory ever launched. But the mission has also had some recent exciting research of a supernova remnant.

Integral is a truly international mission with the participation of all member states of ESA and United States, Russia, the Czech Republic, and Poland. It launched from Baikonur, Kazakhstan on October 17th 2002. It was the first space observatory to simultaneously observe objects in gamma rays, X-rays, and visible light. Gamma rays from space can only be detected above Earth’s atmosphere so Integral circles the Earth in a highly elliptical orbit once every three days, spending most of its time at an altitude over 60 000 kilometres – well outside the Earth’s radiation belts, to avoid interference from background radiation effects. It can detect radiation from events far away and from the processes that shape the Universe. Its principal targets are gamma-ray bursts, supernova explosions, and regions in the Universe thought to contain black holes.

5 metres high and more than 4 tonnes in weight Integral has two main parts. The service module is the lower part of the satellite which contains all spacecraft subsystems, required to support the mission: the satellite systems, including solar power generation, power conditioning and control, data handling, telecommunications and thermal, attitude and orbit control. The payload module is mounted on the service module and carries the scientific instruments. It weighs 2 tonnes, making it the heaviest ever placed in orbit by ESA, due to detectors’ large area needed to capture sparse and penetrating gamma rays and to shield the detectors from background radiation in order to make them sensitive. There are two main instruments detecting gamma rays. An imager producing some of the sharpest gamma-ray images and a spectrometer that gauges gamma-ray energies very precisely. Two other instruments, an X-ray monitor and an optical camera, help to identify the gamma-ray sources.

During its extended ten year mission Integral has has charted in extensive detail the central region of our Milky Way, the Galactic Bulge, rich in variable high-energy X-ray and gamma-ray sources. The spacecraft has mapped, for the first time, the entire sky at the specific energy produced by the annihilation of electrons with their positron anti-particles. According to the gamma-ray emission seen by Integral, some 15 million trillion trillion trillion pairs of electrons and positrons are being annihilated every second near the Galactic Centre, that is over six thousand times the luminosity of our Sun.

A black-hole binary, Cygnus X-1, is currently in the process of ripping a companion star to pieces and gorging on its gas. Studying this extremely hot matter just a millisecond before it plunges into the jaws of the black hole, Integral has discovered that some of it might be escaping along structured magnetic field lines. By studying the alignment of the waves of high-energy radiation originating from the Crab Nebula, Integral found that the radiation is strongly aligned with the rotation axis of the pulsar. This implies that a significant fraction of the particles generating the intense radiation must originate from an extremely organised structure very close to the pulsar, perhaps even directly from the powerful jets beaming out from the spinning stellar core.

Just today ESA reported that Integral has made the first direct detection of radioactive titanium associated with supernova remnant 1987A. Supernova 1987A, located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, was close enough to be seen by the naked eye in February 1987, when its light first reached Earth. Supernovae can shine as brightly as entire galaxies for a brief time due to the enormous amount of energy released in the explosion, but after the initial flash has faded, the total luminosity comes from the natural decay of radioactive elements produced in the explosion. The radioactive decay might have been powering the glowing remnant around Supernova 1987A for the last 20 years.

During the peak of the explosion elements from oxygen to calcium were detected, which represent the outer layers of the ejecta. Soon after, signatures of the material from the inner layers could be seen in the radioactive decay of nickel-56 to cobalt-56, and its subsequent decay to iron-56. Now, after more than 1000 hours of observation by Integral, high-energy X-rays from radioactive titanium-44 in supernova remnant 1987A have been detected for the first time. It is estimated that the total mass of titanium-44 produced just after the core collapse of SN1987A’s progenitor star amounted to 0.03% of the mass of our own Sun. This is close to the upper limit of theoretical predictions and nearly twice the amount seen in supernova remnant Cas A, the only other remnant where titanium-44 has been detected. It is thought both Cas A and SN1987A may be exceptional cases

Christoph Winkler, ESA’s Integral Project Scientist says “Future science with Integral might include the characterisation of high-energy radiation from a supernova explosion within our Milky Way, an event that is long overdue.”

Find out more about Integral here

and about Integral’s study of Supernova 1987A here

Monster Black Holes Lurk at the Edge of Time

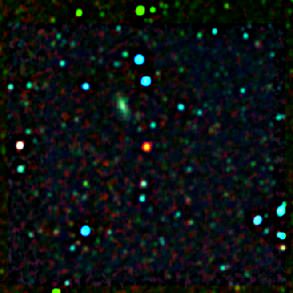

The reddish object in this infrared image is ULASJ1234+0907, located about 11 billion light-years from Earth. The red color comes from vast amounts of dust, which absorbs bluer light, and obscures the supermassive black hole from view in visible wavelengths. Credit: image created using data from UKIDSS and the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) observatory.

As if staring toward the edge of the Universe weren’t fascinating enough, scientists at the University of Cambridge say they see enormous, rapidly growing supermassive black holes barely detectable near the edge of time.

Thick dust shrouds the monster black holes but they emit vast amounts of radiation through violent interactions and collisions with their host galaxies making them visible in the infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum. The team published their results in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The most remote object in the study lies at a whopping 11 billion light-years from Earth. Ancient light from the supermassive black hole, named ULASJ1234+0907 and located toward the constellation of Virgo, the Maiden, has traveled (at almost 10 trillion kilometers, or 6 million million miles, per year) across the cosmos for nearly the estimated age of the Universe. The monster black hole is more than 10 billion times the mass of our Sun and 10,000 times more massive than the black hole embedded in the Milky Way Galaxy; making it one of the most massive black holes ever seen. And it’s not alone. Researchers say that there may be as many as 400 giants black holes in the tiny sliver of the Universe that we can observe.

“These results could have a significant impact on studies of supermassive black holes” said Dr Manda Banerji, lead author of the paper, in a press release. “Most black holes of this kind are seen through the matter they drag in. As the neighbouring material spirals in towards the black holes, it heats up. Astronomers are able to see this radiation and observe these systems.”

The team from Cambridge used infrared surveys being carried out on the UK Infrared Telescope (UKIRT) to peer through the dust and locate the giant black holes for the first time.

“These results are particularly exciting because they show that our new infrared surveys are finding super massive black holes that are invisible in optical surveys,” says Richard McMahon, co-author of the study. “These new quasars are important because we may be catching them as they are being fed through collisions with other galaxies. Observations with the new Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) telescope in Chile will allow us to directly test this picture by detecting the microwave frequency radiation emitted by the vast amounts of gas in the colliding galaxies.”

Huge black holes are known to reside at the centers of all galaxies. Astronomers predict the most massive of these cosmic phenomena grow through violent collisions with other galaxies. Galactic interactions trigger star formation which provides more fuel for black holes to devour. And it’s during this process that thick layers of dust hide the munching black holes.

“Although these black holes have been studied for some time,” says Banergi, “the new results indicate that some of the most massive ones may have so far been hidden from our view. The newly discovered black holes, devouring the equivalent of several hundred Suns every year, will shed light on the physical processes governing the growth of all supermassive black holes.”

Astronomers compare the extreme case of ULASJ1234+0907 with the relatively nearby and well-studied Markarian 231. Markarian 231, found just 600 million light-years away, appears to have recently undergone a violent collision with another galaxy producing an example of a dusty, growing black hole in the local Universe. By contrast, the more extreme example of ULASJ1234+0907, shows scientists that conditions in the early Universe were more turbulent and inhospitable than today.

Astronomers compare the extreme case of ULASJ1234+0907 with the relatively nearby and well-studied Markarian 231. Markarian 231, found just 600 million light-years away, appears to have recently undergone a violent collision with another galaxy producing an example of a dusty, growing black hole in the local Universe. By contrast, the more extreme example of ULASJ1234+0907, shows scientists that conditions in the early Universe were more turbulent and inhospitable than today.

Source: Royal Astronomical Society

Image Credit: Markarian 231, an example of a galaxy with a dusty rapidly growing supermassive black hole located 600 million light years from Earth. The bright source at the center of the galaxy marks the black hole while rings of gas and dust can be seen around it as well as “tidal tails” left over from a recent impact with another galaxy. Courtesy of NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

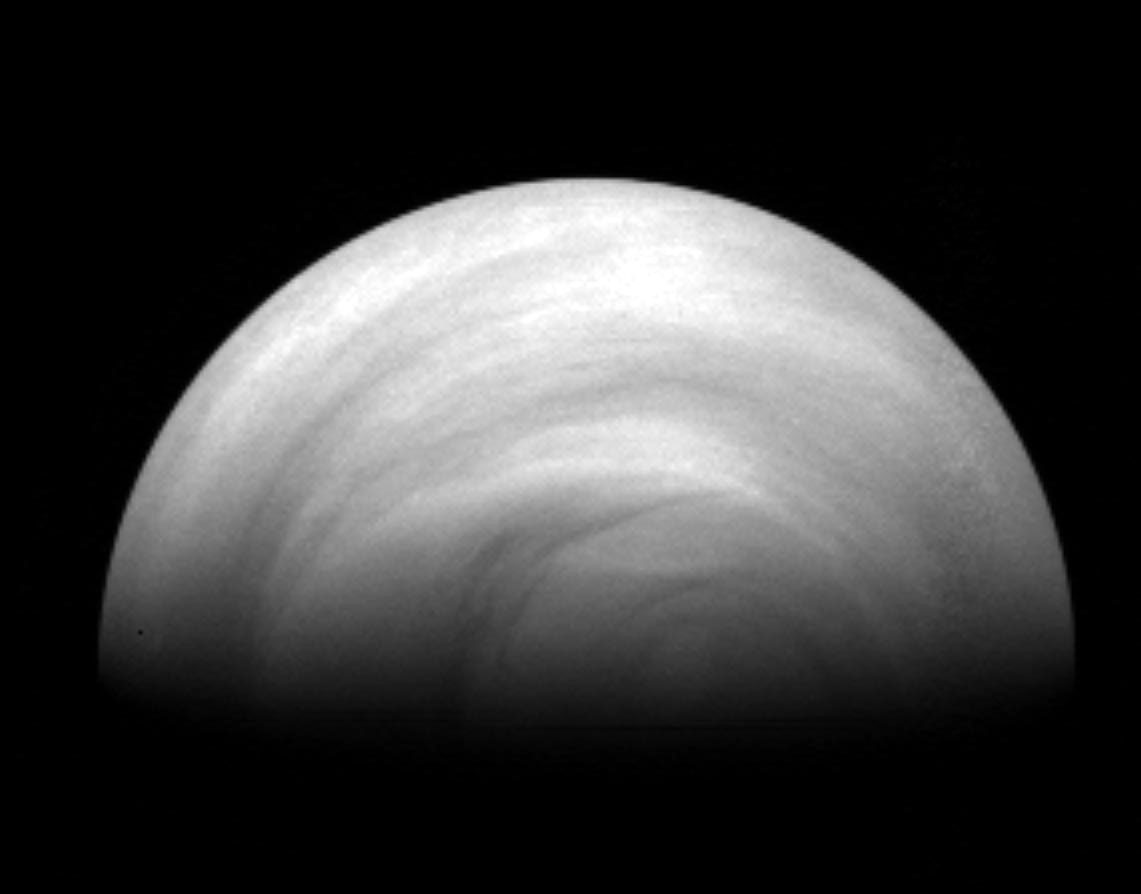

Surprise! Hot Venus has a Cold Upper Atmosphere

Venus’ terminator – the transitional region between day and night — may fuel an unusually cold region in the atmosphere. Credit: ESA/MPS, Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany

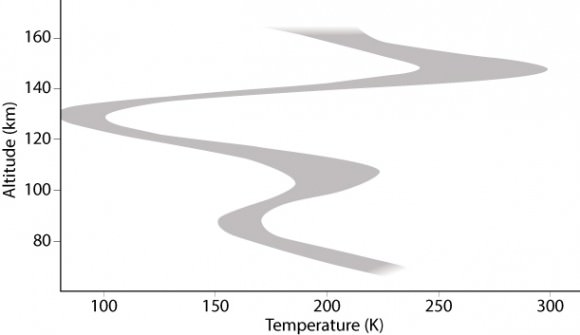

The hottest planet in the Solar System has a surprisingly cold region high in the planet’s atmosphere, according to new findings by the Venus Express spacecraft. While surface temperatures on this hot and hostile planet tops out at 735 Kelvin, or 462 degrees Celsius, ESA scientists say that a layer in the atmosphere about 125 km up has temperatures of around –175 degrees C, and may be cold enough for carbon dioxide to freeze out as ice or snow.

This means this curious cold layer is much colder than any part of Earth’s atmosphere even though Venus is known for its dense, blistering atmosphere and is much closer to the Sun. Additionally, the cold layer appears to be affected by the transitioning between day and night on Venus.

Scientists made the discovery by watching as light from the Sun filtered through the atmosphere to reveal the concentration of carbon dioxide gas molecules at various altitudes along the terminator – the dividing line between the day and night sides of the planet.

Then they combined data about the carbon dioxide concentration with data on atmospheric pressure at each height. The scientists could then calculate the corresponding temperatures.

“Since the temperature at some heights dips below the freezing temperature of carbon dioxide, we suspect that carbon dioxide ice might form there,” said Arnaud Mahieux of the Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy and lead author of the paper reporting the results in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

The temperature profile along the terminator for altitudes of 70–160 km above the surface of Venus. Credit: ESA/AOES–A.V. Bernus

Source: ESA

Clouds of small carbon dioxide ice or snow particles should be very reflective, perhaps leading to brighter than normal sunlight layers in the atmosphere.

“However, although Venus Express indeed occasionally observes very bright regions in the Venusian atmosphere that could be explained by ice, they could also be caused by other atmospheric disturbances, so we need to be cautious,” said Mahieux.

The study also found that the cold layer at the terminator is sandwiched between two comparatively warmer layers.

“The temperature profiles on the hot dayside and cool night side at altitudes above 120 km are extremely different, so at the terminator we are in a regime of transition with effects coming from both sides.

“The night side may be playing a greater role at one given altitude and the dayside might be playing a larger role at other altitudes.”

Similar temperature profiles along the terminator have been derived from other Venus Express datasets, including measurements taken during the transit of Venus earlier this year.

Models are able to predict the observed profiles, but further confirmation will be provided by examining the role played by other atmospheric species, such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen and oxygen, which are more dominant than carbon dioxide at high altitudes.

“The finding is very new and we still need to think about and understand what the implications will be,” says Håkan Svedhem, ESA’s Venus Express project scientist. “But it is special, as we do not see a similar temperature profile along the terminator in the atmospheres of Earth or Mars, which have different chemical compositions and temperature conditions.”

T Minus 9 Days – Mars Orbiters Now in Place to Relay Critical Curiosity Landing Signals

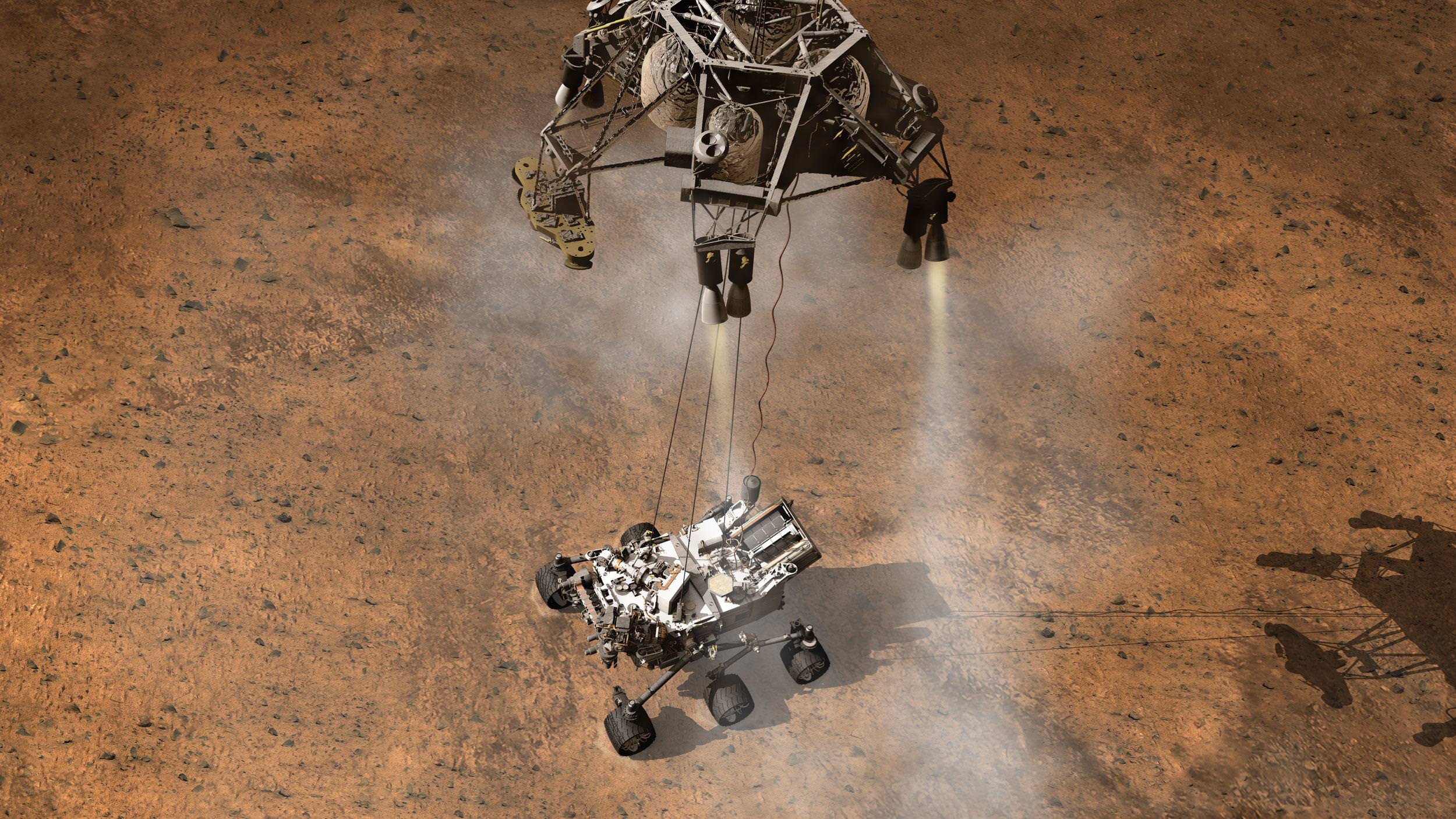

Image Caption: NASA’s Mars Odyssey will relay near real time signals of this artist’s concept depicting the moment that NASA’s Curiosity rover touches down onto the Martian surface. NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and ESA’s Mars Express (MEX) orbiter will also record signals from Curiosity for later playback, not in real time. Credit: NASA

It’s now just T minus 9 Days to the most difficult and complex Planetary science mission NASA has ever attempted ! The potential payoff is huge – Curiosity will search for signs of Martian life

The key NASA orbiter at Mars required to transmit radio signals of a near real-time confirmation of the August 5/6 Sunday night landing of NASA’s car sized Curiosity Mars Science Lab (MSL) rover is now successfully in place, and just in the nick of time, following a successful thruster firing on July 24.

Odyssey will transmit the key signals from Curiosity as she plunges into the Martian atmosphere at over 13,000 MPH (21,000 KPH) to begin the harrowing “7 Minutes of Terror” known as “Entry, Descent and Landing” or EDL – all of which is preprogrammed !

Engines aboard NASA’s long lived Mars Odyssey spacecraft fired for about 6 seconds to adjust the orbiters location about 6 minutes ahead in its orbit. This will allow Odyssey to provide a prompt confirmation of Curiosity’s landing inside Gale crater at about 1:31 a.m. EDT (531 GMT) early on Aug. 6 (10:31 p.m. PDT on Aug. 5) – as NASA had originally planned.

Without the orbital nudge, Odyssey would have arrived over the landing site about 2 minutes after Curiosity landed and the signals from Curiosity would have been delayed.

A monkey wrench was recently thrown into NASA relay signal plans when Odyssey unexpectedly went into safe mode on July 11 and engineers weren’t certain how long recovery operations would take.

“Information we are receiving indicates the maneuver has completed as planned,” said Mars Odyssey Project Manager Gaylon McSmith of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. “Odyssey has been working at Mars longer than any other spacecraft, so it is appropriate that it has a special role in supporting the newest arrival.”

Odyssey has been in orbit at Mars since 2001 conducting orbital science investigations.

Read my review article on Odyssey’s science discoveries – here

Odyssey serves as the primary communications relay for NASA’s other recent surface explorers – Opportunity, Spirit and Phoenix. Opportunity recently passed 3000 Sols of continuous operations.

Two other Mars orbiters, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the European Space Agency’s Mars Express, also will be in position to receive radio transmissions from the Mars Science Laboratory during its descent. However, they will be recording information for later playback, not relaying it immediately, as only Odyssey can.

“We began optimising our orbit several months ago, so that Mars Express will have an orbit that is properly “phased” and provides good visibility of MSL’s planned trajectory,” says Michel Denis, Mars Express Spacecraft Operations Manager.

Mars Express has been orbiting the planet since December 2003.

Image Caption: Mars Express supports Curiosity MSL. Credit: ESA

“NASA supported the arrival of Mars Express at Mars in 2003, and, in the past few years, we have relayed data from the rovers Spirit and Opportunity,” says ESA’s Manfred Warhaut, Head of Mission Operations.

“Mars Express also tracked the descent of NASA’s Phoenix lander in 2008 and we routinely share our deep space networks.

“Technical and scientific cooperation at Mars between ESA and NASA is a long-standing and mutually beneficial activity that helps us both to reduce risk and increase the return of scientific results.”

Watch NASA TV online for live coverage of Curiosity landing: mars.jpl.nasa.gov or www.nasa.gov

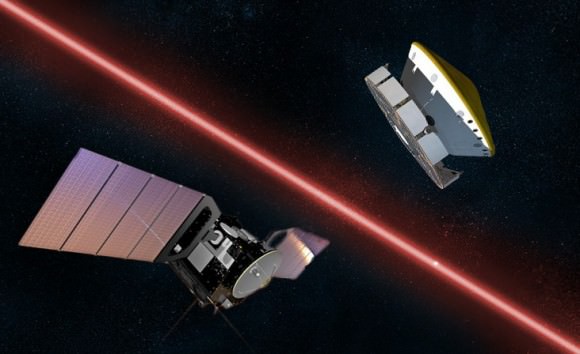

Europe’s Plans to Visit the Moon in 2018

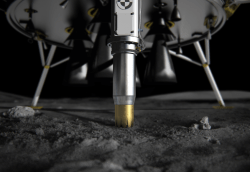

The European Space Agency is aiming for the Moon with their Lunar Lander mission, anticipated to arrive on the lunar surface in 2018. Although ESA successfully put a lander on Titan with the Huygens probe in 2005, this will be the first European spacecraft to visit the surface of Earth’s Moon.

Although Lunar Lander will be an unmanned robotic explorer, the mission will be a forerunner to future human exploration of the Moon as well as Mars. Lunar Lander will use advanced technologies for autonomous landing and will be able to determine the best location for touchdown on its own, utilizing lasers to avoid obstacles on the Moon’s surface.

Although Lunar Lander will be an unmanned robotic explorer, the mission will be a forerunner to future human exploration of the Moon as well as Mars. Lunar Lander will use advanced technologies for autonomous landing and will be able to determine the best location for touchdown on its own, utilizing lasers to avoid obstacles on the Moon’s surface.

With no GPS on the Moon, Lunar Lander will navigate by digitally imaging the surface on the fly. Landing will be accomplished via thrusters, which were successfully tested earlier this year at a test chamber in Germany.

Lunar Lander’s destination will be the Moon’s south pole, where no exploration missions have ever landed. Once on the lunar surface, the Lander will investigate Moon dust using a robotic arm and a suite of onboard diagnostic instruments, sending data and images back to scientists on Earth for further study.

Watch a video of the Lunar Lander mission below, from launch to landing.

Read more about Lunar Lander on the ESA site here.

Images and video: ESA

Aurora Over Antarctica: a “Teardrop From Heaven”

“We managed to snap a few photos before Heaven realised its mistake and closed its doors.”

– Dr. Alexander Kumar

This stunning photo of the Aurora Australis, set against a backdrop of the Milky Way, was captured from one of the most remote research locations on the planet: the French-Italian Concordia Base, located located at 3,200 meters (nearly 10,500 feet) altitude on the Antarctic plateau, 1,670 km (1,037 miles) from the geographic south pole.

The photo was taken on July 18 by resident doctor and scientist Dr. Alexander Kumar and his colleague Erick Bondoux.

Sparked by a coronal mass ejection emitted from active region 11520 on July 12, Earth’s aurorae leapt into high gear both in the northern and southern hemispheres three days later during the resulting geomagnetic storm — giving some wonderful views to skywatchers in locations like Alaska, Scotland, New Zealand… and even the South Pole.

“A raw display of one of nature’s most incredible sights dazzled our crew,” Dr. Kumar wrote on his blog, Chronicles from Concordia. “The wind died down and life became still. To me, it was if Heaven had opened its windows and a teardrop had fallen from high above our station, breaking the dark lonely polar night.

“We managed to snap a few photos before Heaven realised its mistake and closed its doors.”

With winter temperatures as low as -70ºC (-100ºF), no sunlight and no transportation in or out from May to August, Concordia Base is incredibly isolated — so much so that it’s used for research for missions to Mars, where future explorers will face many of the same challenges and extreme conditions that are found at the Base.

With winter temperatures as low as -70ºC (-100ºF), no sunlight and no transportation in or out from May to August, Concordia Base is incredibly isolated — so much so that it’s used for research for missions to Mars, where future explorers will face many of the same challenges and extreme conditions that are found at the Base.

But even though they may be isolated, Dr. Kumar and his colleagues are in an excellent location to witness amazing views of the sky, the likes of which are hard to find anywhere else on Earth. Many thanks to them for braving the bitter cold and otherworldly environment to share images like this with us!

Read more on Concordia Base here.

Lead image: ESA/IPEV/ENEAA/A. Kumar & E. Bondoux. Sub-image: sunset at Concordia. ESA/IPEV/PNRA – A. Kumar