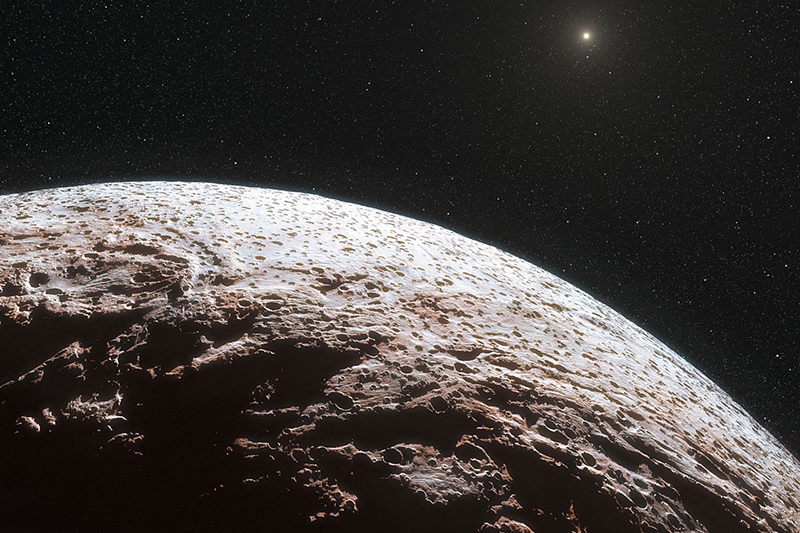

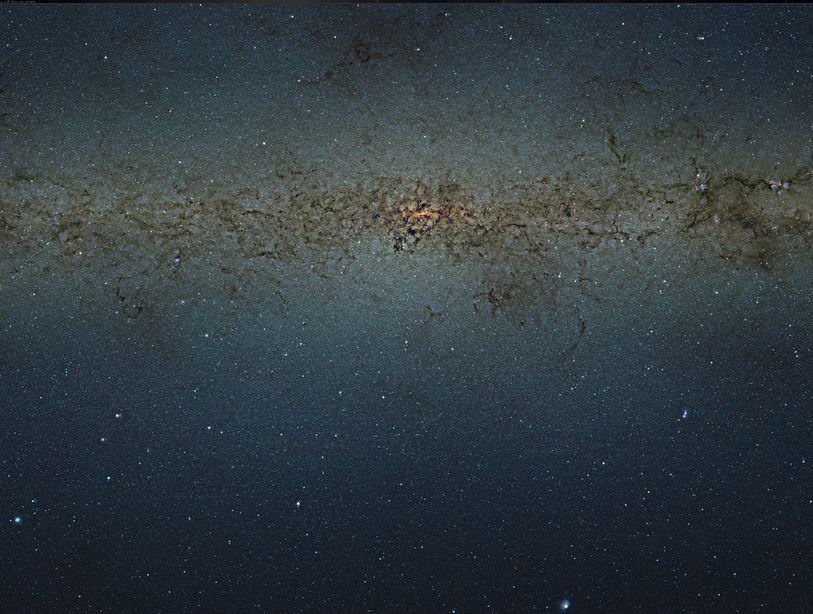

Artist’s impression of the planet around Alpha Centauri B. Credit: ESO

Astronomers have discovered an enticing new planet that could be considered our next-door neighbor. The planet is orbiting a star in the Alpha Centauri system — the closest system to our own, just 4.3 light years away — and the planet has a mass about the same as Earth. It is also the lightest exoplanet ever discovered around a sun-like star. While this planet is likely too hot to contain life as we know it, the star system could possibly host other worlds that could be habitable, researchers from the European Southern Observatory at La Silla say.

“This result represents a major step towards the detection of Earth twins in the immediate vicinity of the Sun,” the team wrote in their paper.

“This is the first planet with a mass similar to Earth ever found around a star like the Sun. Its orbit is very close to its star and it must be much too hot for life as we know it,” said Stéphane Udry from the Geneva Observatory, a co-author of the paper that will be published in Nature on Oct. 17, and member of the team that used the HARPS instrument to find the planet. “But it may well be just one planet in a system of several. Our other HARPS results, and new findings from Kepler, both show clearly that the majority of low-mass planets are found in such systems.”

The planet is called Alpha Centauri Bb and it whips around its star every 3.2 days, orbiting at a distance of just 6 million kilometers (3.6 million miles), closer than Mercury’s orbit around the Sun. (Earth orbits at a comfortable 150 million kilometers (93 million miles) from the Sun.) So it is likely very hot and covered with molten rock, the researchers say.

Many astronomers have thought that the Alpha Centauri system would be a perfect candidate to host Earth-sized worlds. In fact, in 2008, a team of astronomers ran computer simulations of the system’s first 200 million years, and in each instance, despite different parameters, multiple terrestrial planets formed around the star. In every case, at least one planet turned up similar in size to the Earth, and in many cases this planet fell within the star’s habitable zone.

But while astronomers have looked for years, previous searches of planets in the Alpha Centauri system came up empty.

Until now.

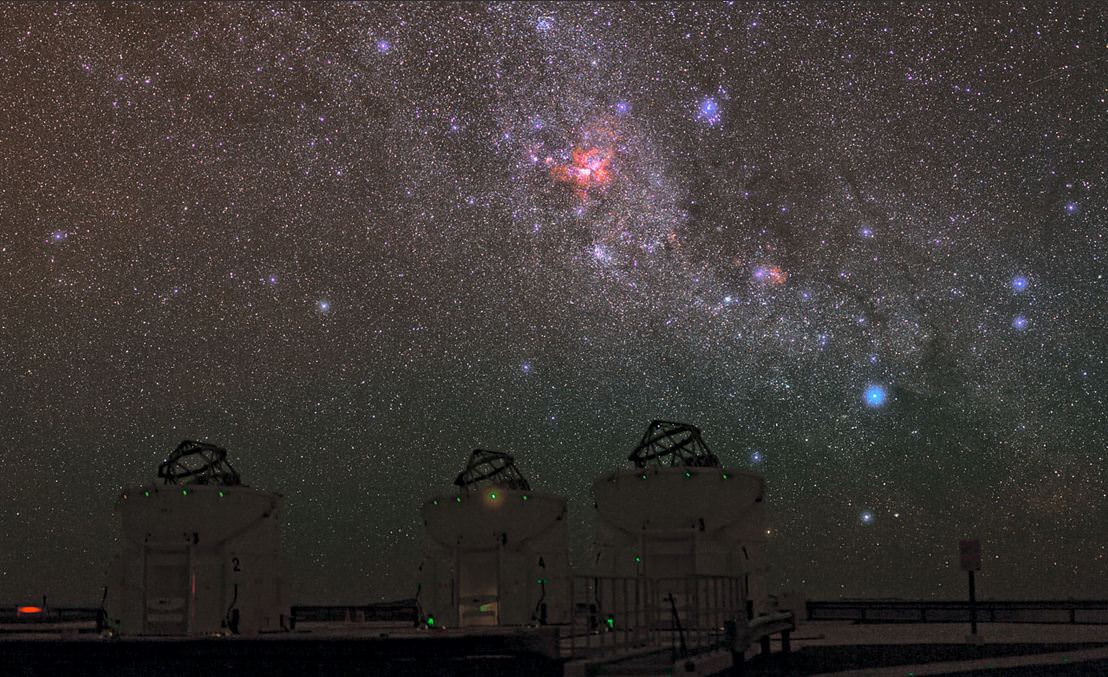

“Our observations extended over more than four years using the HARPS instrument and have revealed a tiny, but real, signal from a planet orbiting Alpha Centauri B every 3.2 days,” says Xavier Dumusque (Geneva Observatory, Switzerland and Centro de Astrofisica da Universidade do Porto, Portugal), lead author of the paper. “It’s an extraordinary discovery and it has pushed our technique to the limit!”

The European team detected the planet by using the radial velocity method — by picking up the tiny wobbles in the motion of the star Alpha Centauri B created by the gravitational pull of the orbiting planet. The effect is extremely small, as it causes the star to move back and forth by no more than 51 centimeters per second (1.8 km/hour). The team said this is the highest precision ever achieved using this method.

Alpha Centauri is one of the brightest stars in the southern skies and is actually a triple star — a system consisting of two stars similar to the Sun orbiting close to each other, designated Alpha Centauri A and B, and a more distant and faint red component known as Proxima Centauri.

Alpha Centauri B is very similar to the Sun but slightly smaller and less bright. The orbit of Alpha Centauri A is hundreds of times further away from the planet, but it would still be a very brilliant object in the planet’s skies.

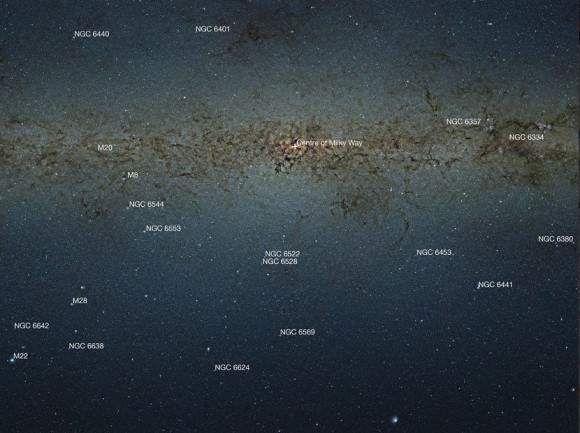

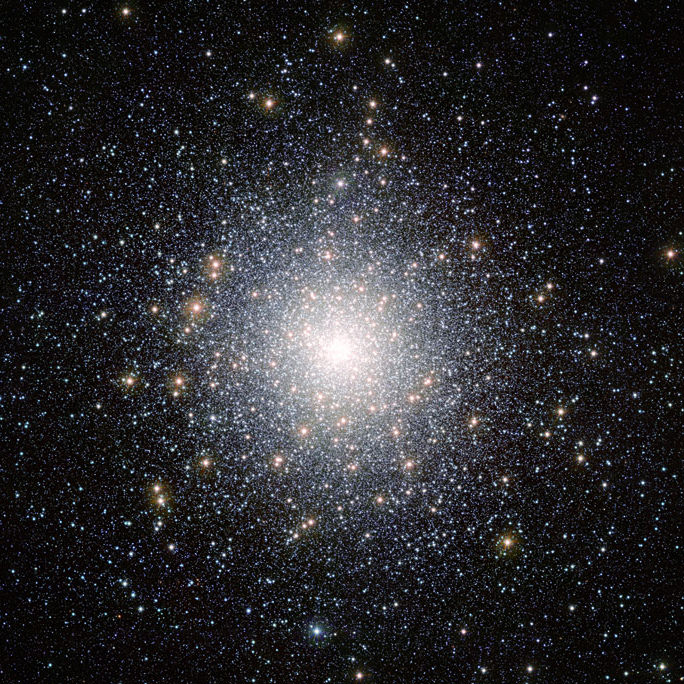

A wide-field view of the sky around Alpha Centauri was created from photographic images forming part of the Digitized Sky Survey 2. The star appears so big just because of the scattering of light by the telescope’s optics as well as in the photographic emulsion. Credit: ESO

The first exoplanet around a Sun-like star was found by the same team back in 1995 and there are now 843 Exoplanets with the addition of Alpha Centauri Bb. Most are much bigger than Earth, and many are as big as Jupiter. The previous closest exoplanet was Epsilon Eridani b, 10.4 light years away.

The challenge astronomers now face is to detect and characterize a planet of mass comparable to the Earth that is orbiting in the habitable zone around another star. The first step has now been taken, the team says.

“This result represents a major step,” said Dumusque. “We live in exciting times!”

So, how long would it take for us to get to this planet? Using current technology, our slowest mode of space transportation, ion drive propulsion, it would take 81,000 years. Using the speeds of one of the fastest spacecraft (Helios 2) and traveling at a constant speed of 240,000 km/hr, it would take about 19,000 years (or over 600 generations) to travel the 4.3 light years.

Read the team’s paper (PDF)

Source: ESO

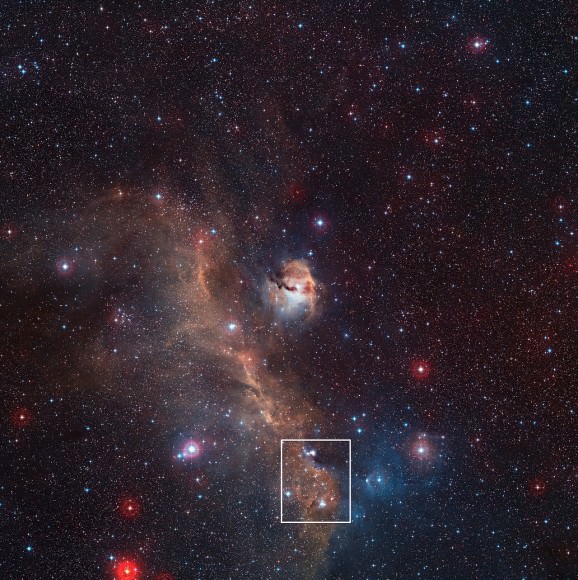

The background stars in the image are part of the Small Magellanic Cloud, which was in the distance behind 47 Tucanae when this image was taken.

The background stars in the image are part of the Small Magellanic Cloud, which was in the distance behind 47 Tucanae when this image was taken.