[/caption]

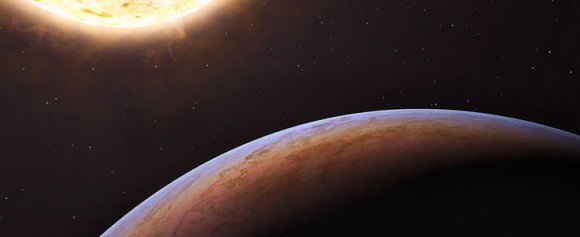

While astronomers have detected over 500 extrasolar planets during the past 15 years, this latest one might have the most storied and unusual past. But its future is also of great interest, as it could mirror the way our own solar system might meet its demise. This Jupiter-like planet, called HIP 13044 b, is orbiting a star that used to be in another galaxy but that galaxy was swallowed by the Milky Way. While astronomers have never directly detected an exoplanet in another galaxy, this offers evidence that other galaxies host stars with planets, too. The star is nearing the end of its life and as it expands, could engulf the planet, just as our Sun will likely snuff out our own world. And somehow, this exoplanet has survived the first death throes of the star.

“The star is in the horizontal branch stage and it still has a planet, which is a glimmer of hope for those of us who worry about how our Solar System will look in 5 billion years,” said Markus Poessel, from the Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie (MPIA) press office.

The star, HIP 13044, lies about 2,000 light-years from Earth in the southern constellation of Fornax (the Furnace). It is part of the so-called Helmi stream, a group of stars that originally belonged to a dwarf galaxy that was devoured by the Milky Way, probably about six to nine billion years ago.

The planet was detected using the radial velocity method — astronomers saw tiny telltale wobbles of the star caused by the gravitational tug of an orbiting companion. The instrument used was FEROS, a high-resolution spectrograph attached to the 2.2-meter MPG/ESO telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile.

“This discovery is very exciting,” says Rainer Klement from MPIA, who selected the target stars for this study. “For the first time, astronomers have detected a planetary system in a stellar stream of extragalactic origin. Because of the great distances involved, there are no confirmed detections of planets in other galaxies. But this cosmic merger has brought an extragalactic planet within our reach.”

Last year, another group of astronomers claimed the detection of an extragalactic exoplanet through “pixel lensing” where the planet passing in front of an even more distant star leads to a subtle, but detectable flash. However, this method relies on a singular event — the chance alignment of a distant light source, planetary system and observers on Earth — and there has been no confirmation of this exoplanet.

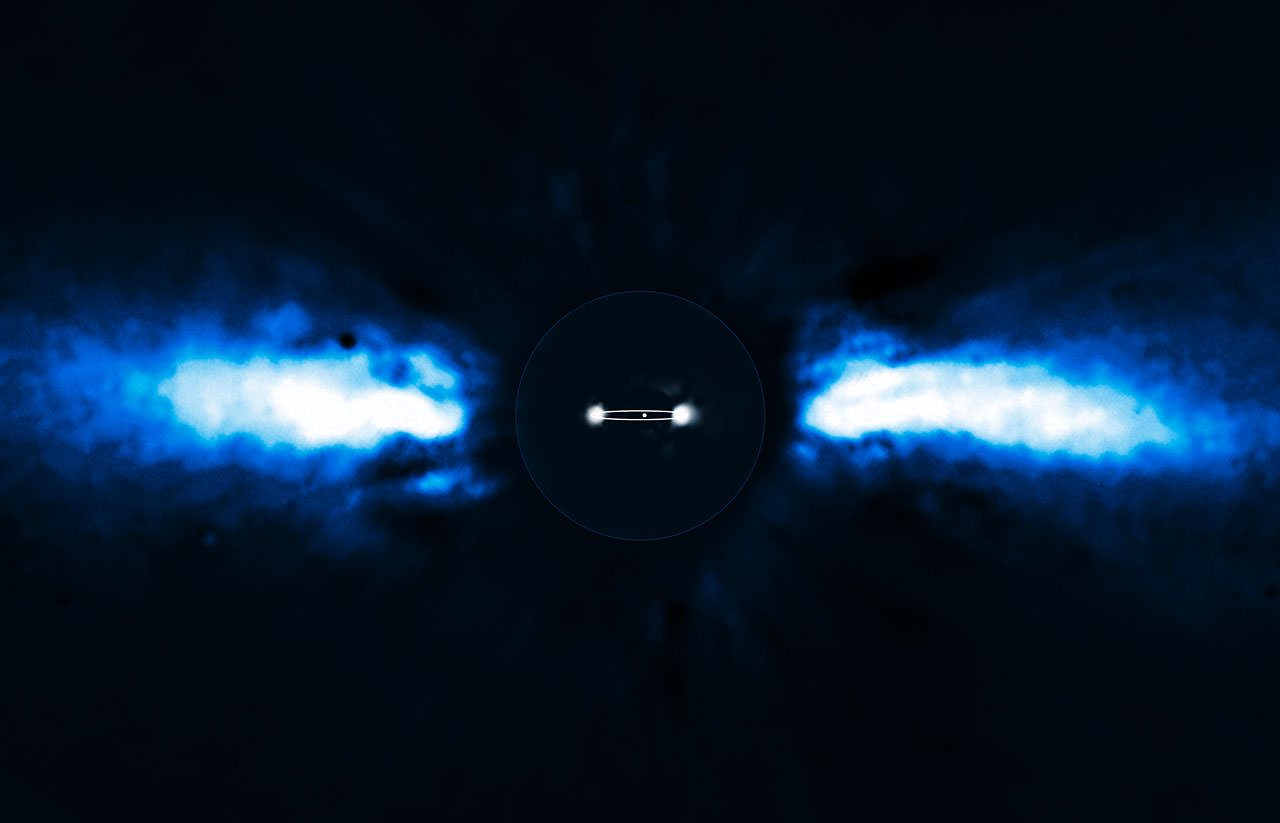

HIP 13044 is in the red giant phase of stellar evolution, and this exoplanet must have survived the period when its host star expanded massively after exhausting the hydrogen fuel supply in its core . The star has now contracted again and is burning helium in its core. Until now, these horizontal branch stars have remained largely uncharted territory for planet-hunters.

“This discovery is part of a study where we are systematically searching for exoplanets that orbit stars nearing the end of their lives,” says Johny Setiawan, also from MPIA, who led the research. “This discovery is particularly intriguing when we consider the distant future of our own planetary system, as the Sun is also expected to become a red giant in about five billion years.”

Our sun is going down the same stellar evolutionary path as HIP 13044, so astronomers may be able to determine the fate of our solar system by studying the system.

Setiawan told Universe Today that he and his team will continue to observe HIP 13044 and other stars in the group to search for other planets. “It is of course difficult to follow how this particular star evolves over time,” he said, “but if you just observe other stars with different evolutionary phase, you can also complete the picture without waiting until this one single star evolves.”

How has this planet survived so far?

“The star is rotating relatively quickly for a horizontal branch star,” said Setiawan. “One explanation is that HIP 13044 swallowed its inner planets during the red giant phase, which would make the star spin more quickly.”

HIP 13044b probably once orbited much farther away from the star but spiraled inwards as the star began to spin faster.

The star also poses interesting questions about how giant planets form, as the star appears to contain very few elements heavier than hydrogen and helium — fewer than any other star known to host planets, and Setiawan said it is a puzzle how such a star could have formed a planet.

“There is indeed a possibility to form planets around metal-poor stars due to gravitational disk instability, which is an alternative to the core accretion model,” Setiawan said in an email. “But, for such a very metal poor star like HIP 13044, I am also not completely sure if the disk instability model can also explain the whole process. Still, it is probably the best explanation for this particular system.”

Source: Max Planck institute for Astronomy, ESO, email exchange with Setiawan