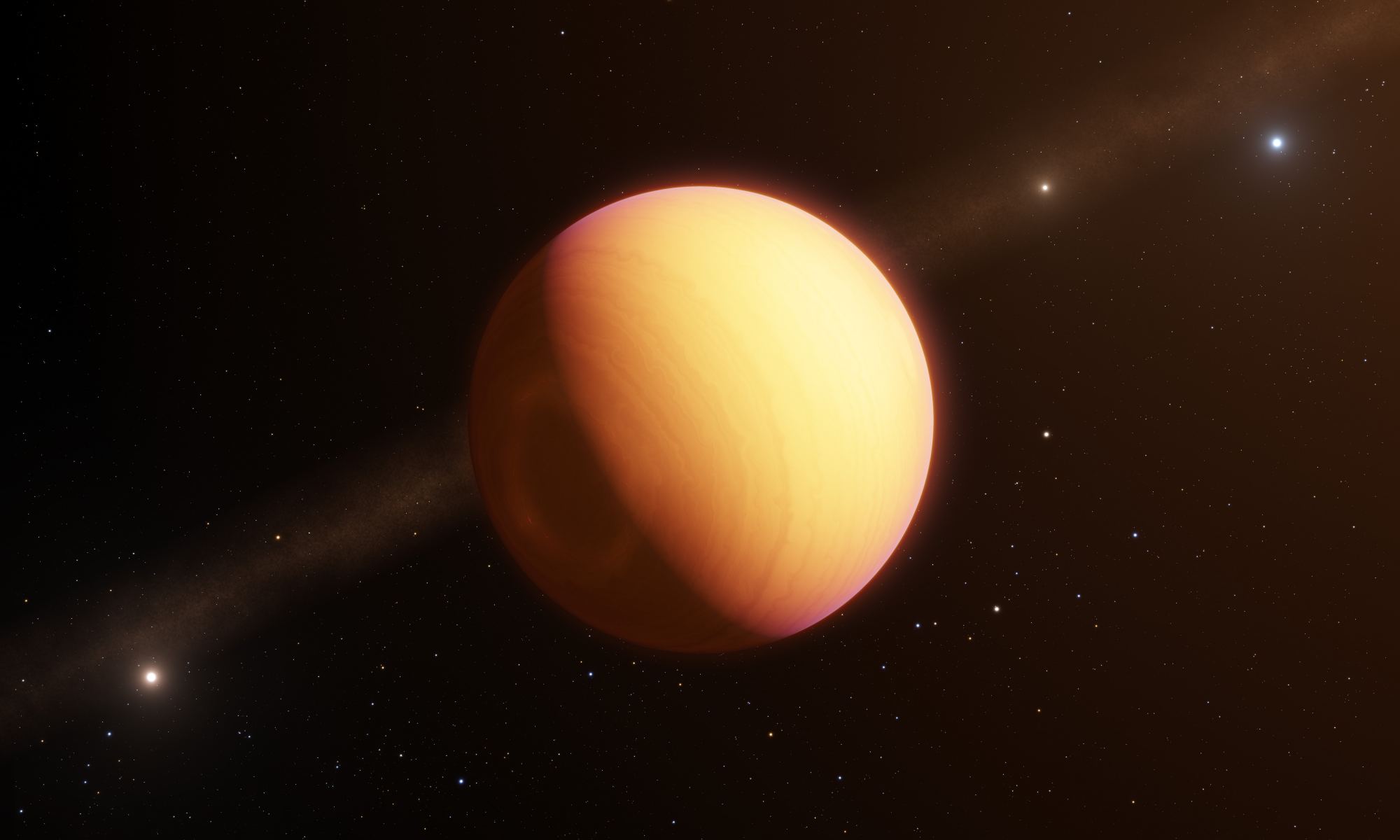

We’ve finally got our first optical look at an exoplanet and its atmosphere, and boy is it a strange place. The planet is called HR8799e, and its atmosphere is a complex one. HR8799e is in the grips of a global storm, dominated by swirling clouds of iron and silicates.

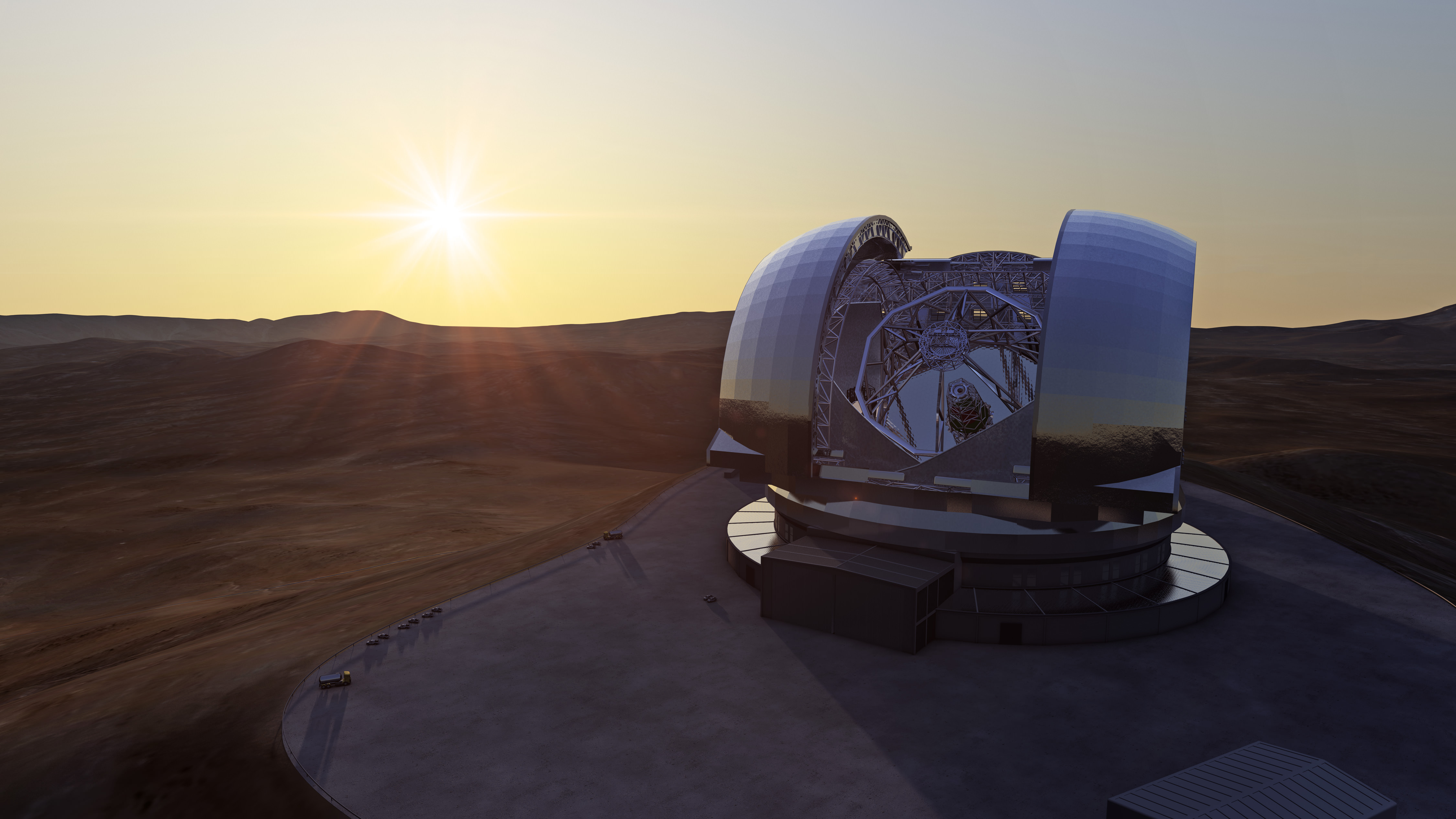

Continue reading “Ground-Based Telescope Directly Observes the Atmosphere of an Extrasolar Planet, and Sees Swirling Clouds of Iron and Silicates”Ground-Based Telescope Directly Observes the Atmosphere of an Extrasolar Planet, and Sees Swirling Clouds of Iron and Silicates