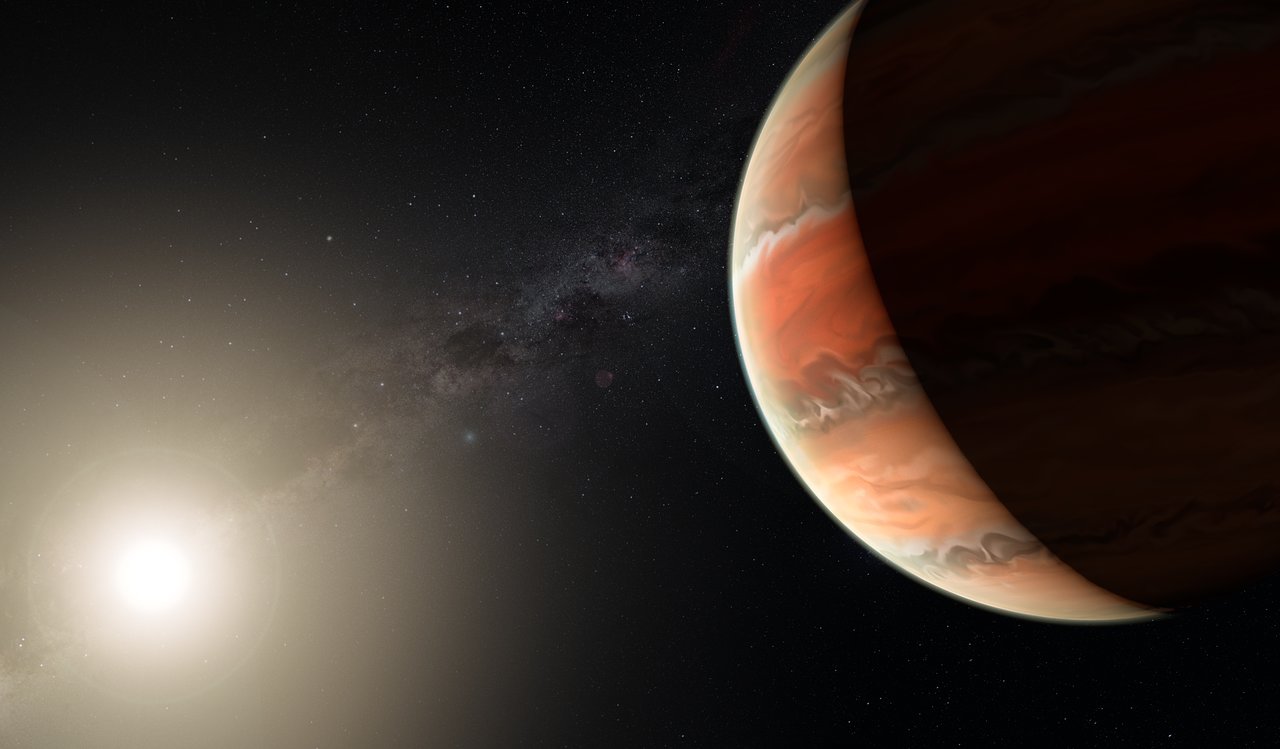

Proxima Centauri, in addition to being the closest star system to our own, is also the home of the closest exoplanet to Earth. The existence of this planet, Proxima b, was first announced in August of 2016 and then confirmed later that month. The news was met with a great deal of excitement, and a fair of skepticism, as numerous studies followed t were dedicated to determining if this planet could in fact be habitable.

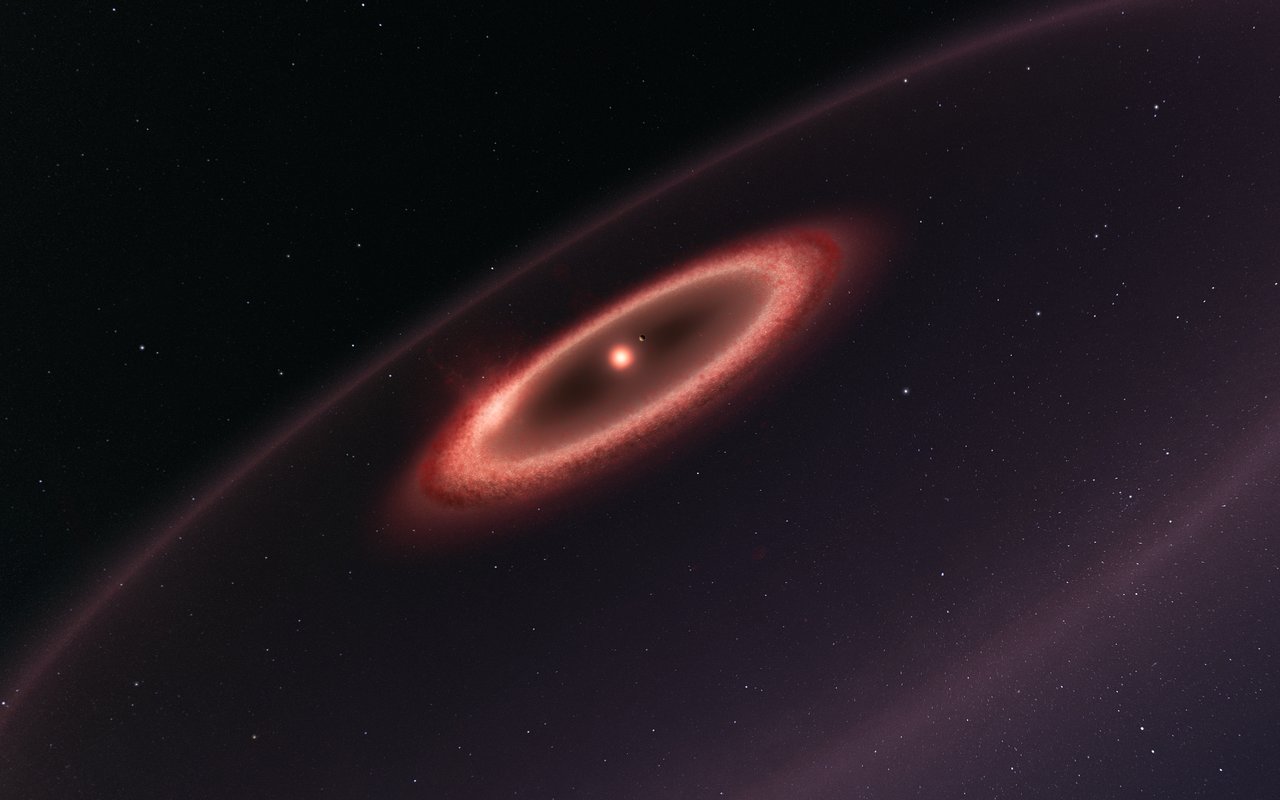

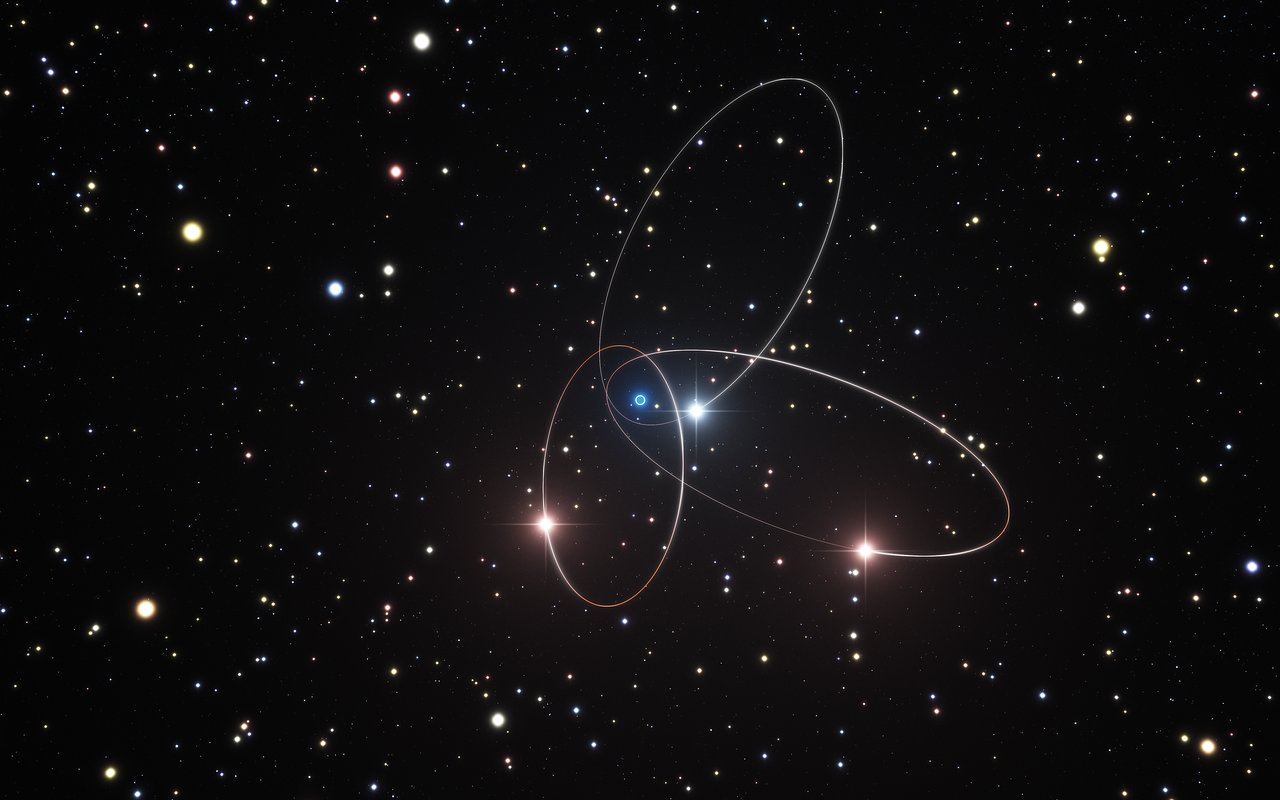

Another important question has been whether or not Proxima Centauri could have any more objects orbiting it. According to a recent study by an international team of astronomers, Proxima Centauri is also home to a belt of cold dust and debris that is similar to the Main Asteroid Belt and Kuiper Belt in our Solar System. The existence of this dusty belt could indicate the presence of more planets in this star system.

The study, titled “ALMA Discovery of Dust Belts Around Proxima Centauri“, recently appeared online and is scheduled to appear in the Monthly Notices of the Astronomical Society. The study was led by Guillem Anglada from the Astrophysical Institute of Andalusia (CSIS), and included members from the Institute of Space Sciences (IEEC), the European Southern Observatory (ESO), the Joint ALMA Observatory, and multiple universities.

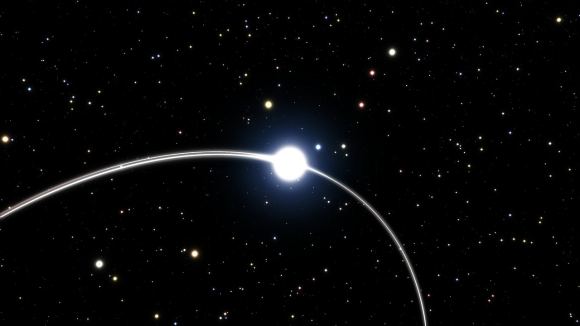

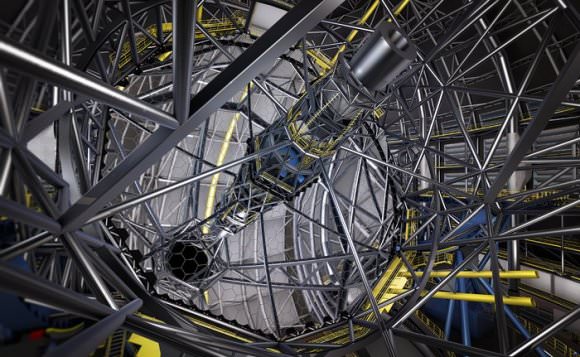

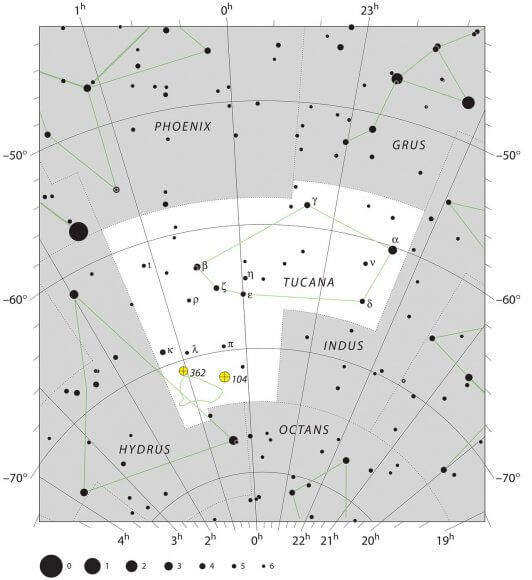

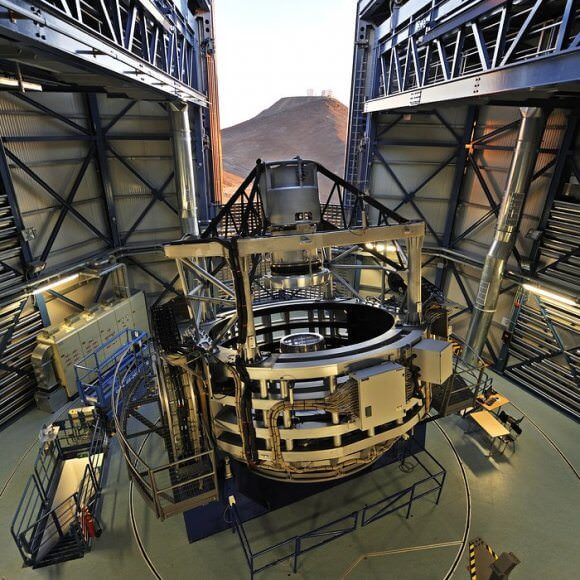

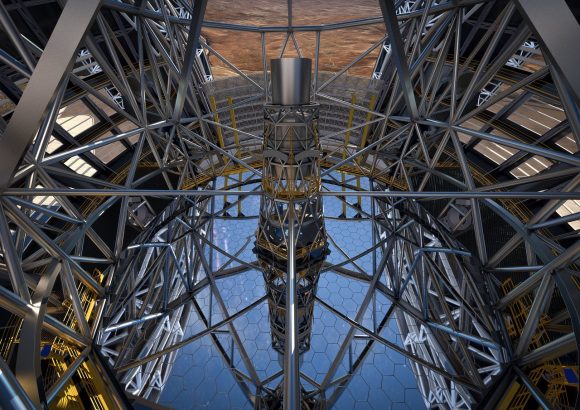

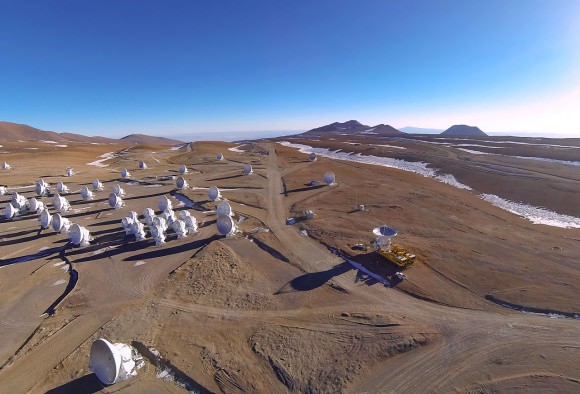

For their study, the team relied on data obtained by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimter Array (ALMA) at the ALMA Observatory in Chile. These observations revealed the glow of a cold dust belt that is roughly 1 to 4 AUs from Proxima Centauri – one to four times the distance between the Earth and the Sun. This puts it significantly further out than Proxima b, which orbits its sun at a distance of 0.0485 AU (~5% of Earth’s distance from the Sun).

Dust belts are essentially the leftover material that did not form into larger bodies withing a star system. The particles of rock and ice in these belts vary in size from being smaller than a millimeter across to asteroids that are many kilometers in diameter. Based on their observations, the team estimated that the belt in Proxima Centauri has a total mass that is about one-hundredth the mass of Earth.

The team also estimated that this belt experiences temperatures of about 43 K (-230°C; -382 °F), making it as cold as the Kuiper Belt. As Dr. Anglada explained the significance of these findings in a recent ESO press release:

“The dust around Proxima is important because, following the discovery of the terrestrial planet Proxima b, it’s the first indication of the presence of an elaborate planetary system, and not just a single planet, around the star closest to our Sun.”

The ALMA data also provided indications that Proxima Centauri might also have another belt located about ten times further out. In other words, Proxima Centauri may have two belts, just like our Solar System. If confirmed, this could indicate that this neighboring star also has a system of planets that fall within and between belts of unconsolidated material, which in turn is leftover from the early days of planet formation. As Dr. Anglada explained:

“This result suggests that Proxima Centauri may have a multiple planet system with a rich history of interactions that resulted in the formation of a dust belt. Further study may also provide information that might point to the locations of as yet unidentified additional planets.”

The very cold environment of this outer belt could also have some interesting implications, since its parent star is much dimmer than our own. Pedro Amado, who also hails from the Astrophysical Institute of Andalusia, was similarly enthusiastic about these findings. As he indicated, they are just the beginning of what is sure to be a long process of discovery about this system.

“These first results show that ALMA can detect dust structures orbiting around Proxima,” he said. “Further observations will give us a more detailed picture of Proxima’s planetary system. In combination with the study of protoplanetary discs around young stars, many of the details of the processes that led to the formation of the Earth and the Solar System about 4600 million years ago will be unveiled. What we are seeing now is just the appetiser compared to what is coming!”

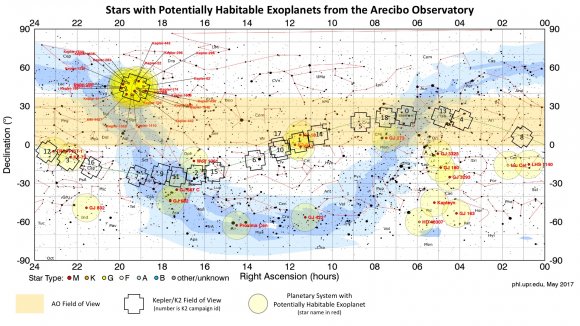

This study is also likely to be of interest to those planning on conducting direct observations of the Alpha Centauri system, such as Project Blue. In the coming years, they hope to deploy a space telescope that will observe Alpha Centauri directly to study any exoplanets it may have. With a slight adjustment, this telescope could also take a gander at Proxima Centauri and aid in the hunt for a system of planets there.

And then there’s Breakthrough Starshot, the first proposed interstellar voyage which hopes to send a laser sail-driven nanocraft to Alpha Centauri in the coming decades. Recently, the scientists behind Starshot discussed the possibility of extending the mission to include a stopover in Proxima Centauri. Before such a mission can take place, the planners need to know what kind of dusty environment awaits it.

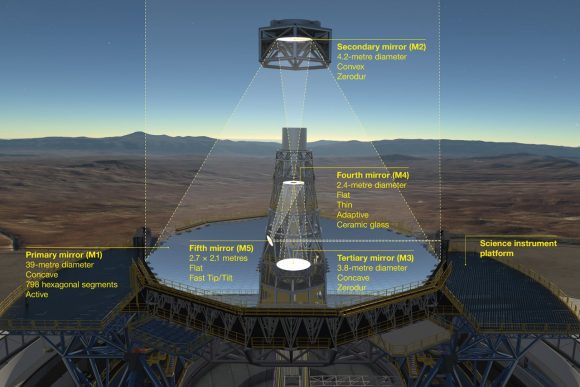

And of course, future studies will benefit from the deployment of next-generation instruments, like the James Webb Space Telescope (scheduled for launch in 2019) and the ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) – which is expected to collect its first light in 2024.