Never heard of the Eta Aquarid meteors? 2019 offers a good chance to check out this normally obscure meteor shower.

Continue reading “Keep an Eye Out for the Eta Aquarid Meteors This Weekend”Keep an Eye Out for the Eta Aquarid Meteors This Weekend

Never heard of the Eta Aquarid meteors? 2019 offers a good chance to check out this normally obscure meteor shower.

Continue reading “Keep an Eye Out for the Eta Aquarid Meteors This Weekend”

An Eta Aquarid meteor captured on video by astrophotographer Justin Ng shows an amazing explodingred meteor and what is known as a persistent train — what remains of a meteor fireball in the upper atmosphere as winds twist and swirl the expanding debris.

The meteor pierced through the clouds and the vaporized “remains” of the fireball persisted for over 10 minutes, Justin said. It lasts just a few seconds in the time-lapse.

Here’s the video:

Justin took this footage during an astrophotography tour to Mount Bromo in Indonesia, where he saw several Eta Aquarid meteors. The red, explody meteor occurred at around 4:16 am,local time. The Small Magellanic Cloud is also visible just above the horizon on the left.

Eta Aquarid meteor piercing through cloud and left behind a red smoke trail that lasted for over 10mins. Taken in Mt. Bromo 8hrs ago. pic.twitter.com/WtFl9TGRbj

— Justin Ng (@justinngphoto) May 6, 2017

Persistent trains occur when a meteoroid blasts through the air, ionizes gases in our atmosphere. Until recently, these have been difficult to study because they are rather elusive. But lately, with the widespread availability of ultra-fast lenses and highly sensitive cameras, capturing these trains is becoming more common, much to the delight of astrophotography fans!

Mount Bromo, 2,329 meters (7600 ft.) high is an active volcano in East Java, Indonesia.

Check out more of Justin’s work at his website, on Twitter, Facebook or G+.

6 May 2017 – Eta Aquarid Captured at Mount Bromo (4K Timelapse) from Justin Ng Photo on Vimeo.

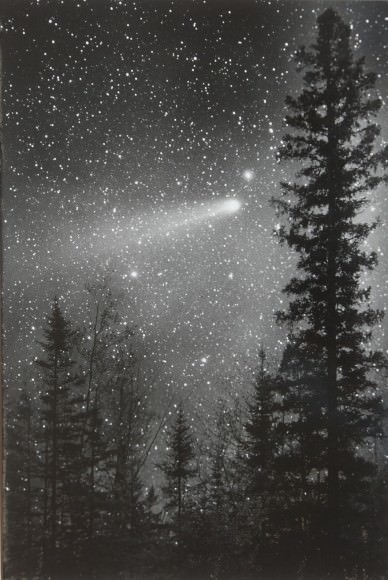

Halley’s Comet may be at the far end of its orbit 3.2 billion miles (5.1 billion km) from Earth, but this week fragments of it will burn up as meteors in the pre-dawn sky as the Eta Aquarid meteor shower. The comet last passed our way in 1986, pivoted about the Sun and began the long return journey to the chilly depths of deep space.

Today, Halley’s a magnitude +25 speck in the constellation Hydra. Although utterly invisible in most telescopes, you can imagine it below tonight’s half-moon near the outermost point in its orbit four Earth-sun distances beyond Neptune. Literally cooling its jets, the comet mulls its next Earth flyby slated for summer 2061.

Some meteor showers have sharp peaks, others like the Eta Aquarids, a broad, plateau-like maximum. The shower’s been active since mid-April and will continue right up till the end of this month with the peak predicted Saturday morning May 6. Observers in tropical latitudes, where the constellation Aquarius rises higher than it does from my home in northern Minnesota, will spy 25-30 meteors an hour from a dark sky in the hour or two before dawn.

Skywatchers further north will see fewer meteors because the radiant will be lower in the sky; meteors that flash well below the radiant get cut off by the horizon, reducing the rate by about half ( about 10-15 meteors an hour). That’s still a decent show. I got up with the first robins a couple years back to see the shower and was pleasantly surprised with a handful of flaming Halley particles in under a half hour.

While a low radiant means fewer meteors, there’s an up side. You have a fair chance of seeing an earthgrazer, a meteor that skims tangent to the upper atmosphere, flaring for many seconds before either burning up or skipping back off into space.

The Eta Aquarids will be active all week. With the peak occurring Saturday morning, you should be able to see at least a few prior to dawn each morning. The quarter-to-waxing gibbous moon will set in plenty of time through Friday morning, leaving dark skies, but cuts it close Saturday when it sets about the same time the radiant rises in the east.

For best viewing, find as dark a place as possible with an open view to the east and south. I like to tote out a reclining lawn chair, face east and get comfy under a warm sleeping bag or wool blanket. Since twilight starts about an hour and three-quarters before your local sunrise, plan to be out watching an hour before that or around 3:30 a.m. I know, I know. That sounds harsh, but I’ve discovered that once you make the commitment, the act of watching a meteor shower becomes a relaxed pleasure punctuated by the occasional thrill of seeing a bright meteor.

You’ll be in magnificent company, too. The Milky Way rides high across the southeastern sky at that hour, and Saturn gleams due south in Sagittarius at the start of dawn. If you’d like to contribute observations of the shower to help meteor scientists better understand its behavior and evolution, check out the International Meteor Organization’s Eta Aquariids 2017 campaign for more information.

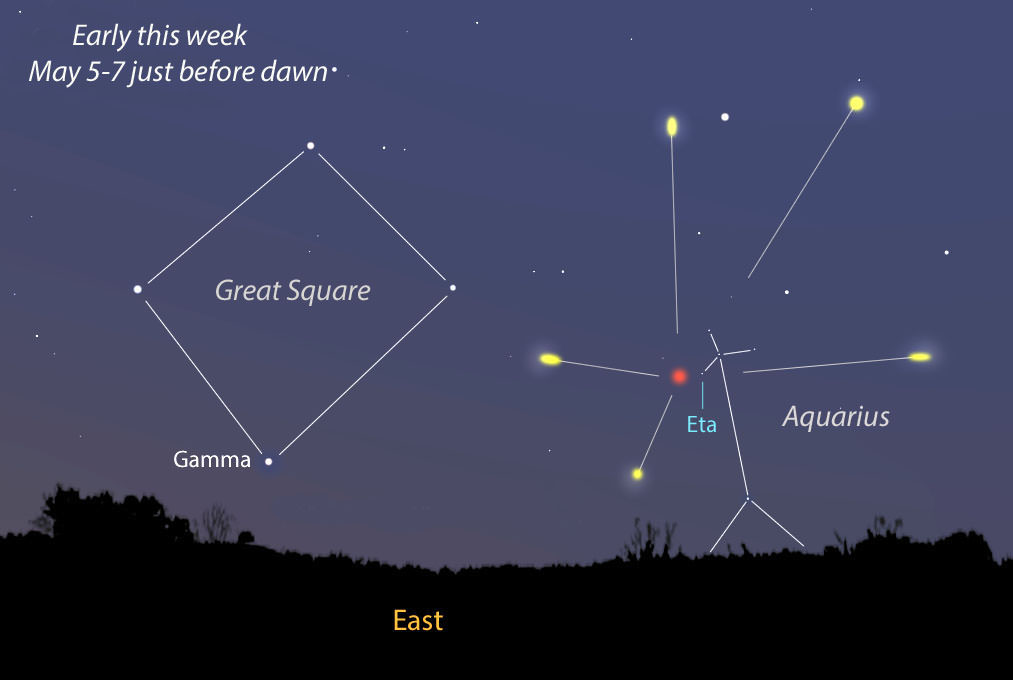

Itching to watch a meteor shower and don’t mind getting up at an early hour? Good because this should be a great year for the annual Eta Aquarid (AY-tuh ah-QWAR-ids) shower which peaks on Thursday and Friday mornings May 5-6. While the shower is best viewed from tropical and southern latitudes, where a single observer might see between 25-40 meteors an hour, northern views won’t be too shabby. Expect to see between 10-15 per hour in the hours before dawn.

Most showers trace their parentage to a particular comet. The Perseids of August originate from dust strewn along the orbit of comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which drops by the inner solar system every 133 years after “wintering” for decades just beyond the orbit of Pluto.

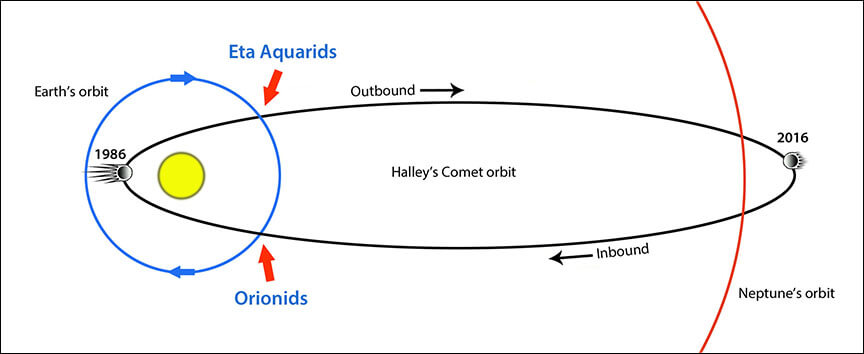

The upcoming Eta Aquarids have the best known and arguably most famous parent of all: Halley’s Comet. Twice each year, Earth’s orbital path intersects dust and minute rock particles strewn by Halley during its cyclic 76-year journey from just beyond Uranus to within the orbit of Venus.

Our first pass through Halley’s remains happens this week, the second in late October during the Orionid meteor shower. Like bugs hitting a windshield, the grains meet their demise when they smash into the atmosphere at 147,000 mph (237,000 km/hr) and fire up for a brief moment as meteors. Most comet grains are only crumb-sized and don’t have a chance of reaching the ground as meteorites. To date, not a single meteorite has ever been positively associated with a particular shower.

The farther south you live, the higher the shower radiant will appear in the sky and the more meteors you’ll spot. A low radiant means less sky where meteors might be seen. But it also means visits from “earthgrazers”. These are meteors that skim or graze the atmosphere at a shallow angle and take many seconds to cross the sky. Several years back, I saw a couple Eta Aquarid earthgrazers during a very active shower. One other plus this year — no moon to trouble the view, making for ideal conditions especially if you can observe from a dark sky.

From mid-northern latitudes the radiant or point in the sky from which the meteors will appear to originate is low in the southeast before dawn. At latitude 50° north the viewing window lasts about 1 1/2 hours before the light of dawn encroaches; at 40° north, it’s a little more than 2 hours. If you live in the southern U.S. you’ll have nearly 3 hours of viewing time with the radiant 35° high.

Grab a reclining chair, face east and kick back for an hour or so between 3 and 4:30 a.m. An added bonus this spring season will be hearing the first birdsong as the sky brightens toward the end of your viewing session. And don’t forget the sights above: a spectacular Milky Way arching across the southern sky and the planets of Mars and Saturn paired up in the southwestern sky.

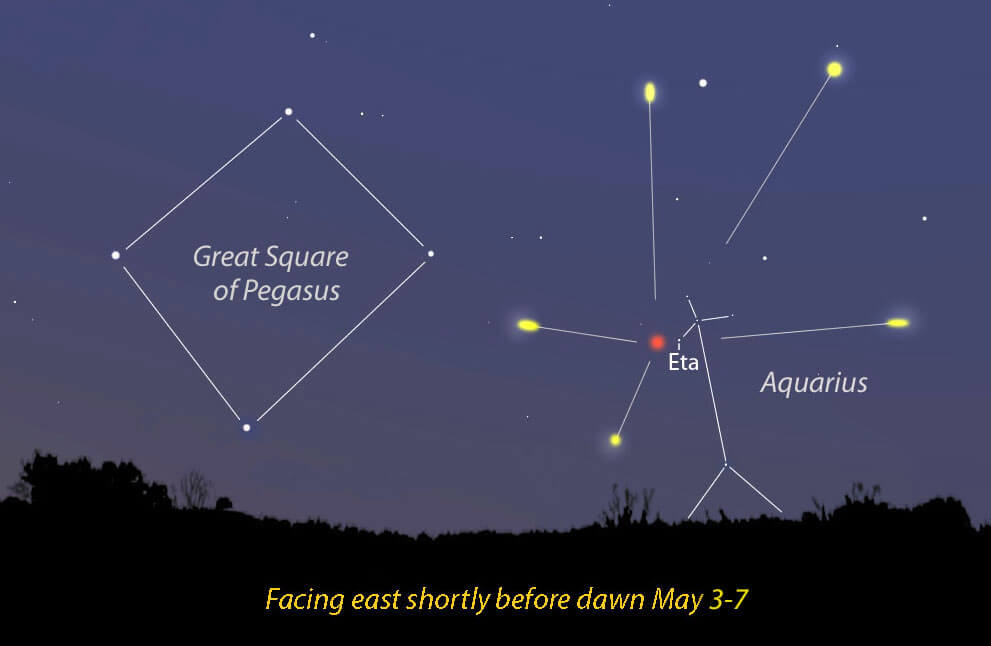

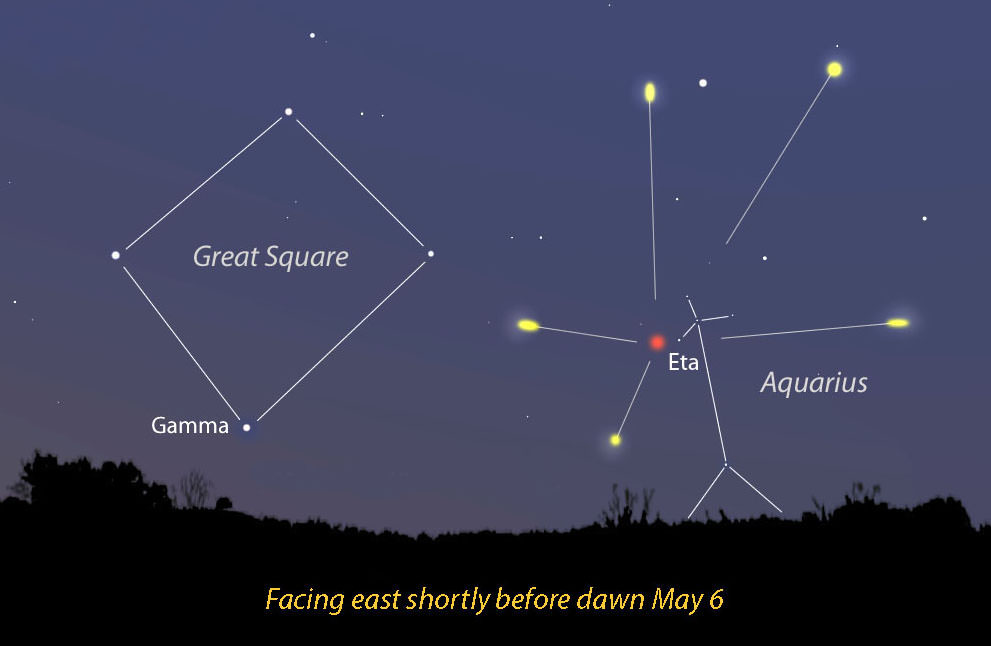

Meteor shower members can appear in any part of the sky, but if you trace their paths in reverse, they’ll all point back to the radiant. Other random meteors you might see are called sporadics and not related to the Eta Aquarids. Meteor showers take on the name of the constellation from which they originate.

Aquarius is home to at least two showers. This one’s called the Eta Aquarids because it emanates from near the star Eta Aquarii. An unrelated shower, the Delta Aquarids, is active in July and early August. Don’t sweat it if weather doesn’t cooperate the next couple mornings. The shower will be active throughout the weekend, too.

Happy viewing and clear skies!

UPDATE: Watch a live webcast of the meteor shower, below, from NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center during the night of Monday, May 5 to the early morning of May 6.

Halley’s Comet won’t be back in Earth’s vicinity until the summer of 2061, but that doesn’t mean you have to wait 47 years to see it. The comet’s offspring return this week as the annual Eta Aquarid meteor shower. Most meteor showers trace their parentage to a particular comet. The Perseids of August originate from dust strewn along the orbit of comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which drops by the inner solar system every 133 years after “wintering” for decades just beyond the orbit of Pluto, but the Eta Aquarids (AY-tuh ah-QWAR-ids) have the best known and arguably most famous parent of all – Halley’s Comet. Twice each year, Earth’s orbital path intersects dust and rock particles strewn by Halley during its cyclic 76-year journey from just beyond Uranus to within the orbit of Venus. When we do, the grit meets its demise in spectacular fashion as wow-inducing meteors.

Meteoroids enter the atmosphere and begin to glow some 70 miles high. The majority of them range from sand to pebble sized but most no more than a gram or two. Speeds range from 25,000-160,000 mph (11-72 km/sec) with the Eta Aquarids right down the middle at 42 miles per second (68 km/sec). Most burn white though ‘burn’ doesn’t quite hit the nail on the head. While friction with the air heats the entering meteoroid, the actual meteor or bright streak is created by the speedy rock exciting atoms along its path. As the atoms return to their neutral state, they emit light. That’s what we see as meteors. Picture them as tubes of glowing gas.

The farther south you live, the higher the shower radiant will appear in the sky and the more meteors you’ll see. For southern hemisphere observers this is one of the better showers of the year with rates around 30-40 meteors per hour. With no moon to brighten the sky, viewing conditions are ideal. Except for maybe the early hour. The shower is best seen in the hour or two before the start of dawn.

From mid-northern latitudes the radiant or point in the sky from which the meteors will appear to originate is low in the southeast before dawn. At latitude 50 degrees north the viewing window lasts about 1 1/2 hours; at 40 degrees north, it’s a little more than 2 hours. If you live in the southern U.S. you’ll have nearly 3 hours of viewing time with the radiant 35 degrees high.

Northerners might spy 5-10 meteors per hour over the next few mornings. Face east for the best view and relax in a reclining chair. One good thing about this event – it won’t be anywhere near as cold as watching the December Geminids or January’s Quadrantids. We must be grateful whenever we can.

Meteor shower members can appear in any part of the sky, but if you trace their paths in reverse, they’ll all point back to the radiant. Other random meteors you might see are called sporadics and not related to the Eta Aquarids. Because Aquarius is home to at least two radiants, we distinguish the Etas, which radiate from near Eta Aquarii, from the Delta Aquarids, an unrelated shower active in July and August.

Wishing you clear skies and plenty of hot coffee at the ready.