It has been thought that the existence of plate tectonics has been a significant factor in the shaping of our planet and the evolution of life. Mars and Venus don’t experience such movements of crustal plates but then the differences between the worlds is evident. The exploration of exoplanets too finds many varied environments. Many of these new alien worlds seem to have significant internal heating and so lack plate movements too. Instead a new study reveals that these ‘Ignan Earths’ are more likely to have heat pipes that channel magma to she surface. The likely result is a surface temperature similar to Earth in its hottest period when liquid water started forming.

Continue reading “Planets Without Plate Tectonics Could Still Be Habitable”Life Might Thrive on the Surface of Earth for an Extra Billion Years

The Sun is midway through its life of fusion. It’s about five billion years old, and though its life is far from over, it will undergo some pronounced changes as it ages. Over the next billion years, the Sun will continue to brighten.

That means things will change here on Earth.

Continue reading “Life Might Thrive on the Surface of Earth for an Extra Billion Years”Evolutionary Biology: Why study it? What can it teach us about finding life beyond Earth?

Universe Today has had the incredible opportunity of exploring various scientific fields, including impact craters, planetary surfaces, exoplanets, astrobiology, solar physics, comets, planetary atmospheres, planetary geophysics, cosmochemistry, meteorites, radio astronomy, extremophiles, organic chemistry, black holes, cryovolcanism, planetary protection, dark matter, supernovae, neutron stars, and exomoons, and how these separate but unique all form the basis for helping us better understand our place in the universe.

Continue reading “Evolutionary Biology: Why study it? What can it teach us about finding life beyond Earth?”Could We Live Without Kilonovae?

It’s a classic statement shared at many public outreach events…’we are made of stardust’. It is true enough that the human body is mostly water with some other elelments like carbon which are formed inside stars just like the Sun. It’s not just common elements like carbon though for we also have slighly more rare elements like iodine and bromine. They don’t form in normal stars but instead are generated in collisions between neutron stars! It poses an interesting question, without the neutron star merger event; ‘would we exist?’

Continue reading “Could We Live Without Kilonovae?”The Early Earth was Really Horrible for Life

Earth has had a long and complex history since its formation roughly 4.5 billion years ago. Initially, it was a molten ball, but eventually, it cooled and became differentiated. The Moon formed from a collision between Earth and a protoplanet named Theia (probably), the oceans formed, and at some point in time, about 4 billion years ago, simple life appeared.

Those are the broad strokes, and scientists have worked hard to fill in a detailed timeline of Earth’s history. But there are a host of significant and poorly-understood periods in the timeline, lined up like targets for the scientific method. One of them concerns UV radiation and its effects on early life.

A new study probes the effects of UV radiation on Earth’s early life-forms and how it might have shaped our world.

Continue reading “The Early Earth was Really Horrible for Life”Life on Earth Needed Iron. Will it be the Same on Other Worlds?

A lot has to go right for a planet to support life. Some of the circumstances that allow life to bloom on any given planet stem from the planet’s initial formation. Here on Earth, circumstances meant Earth’s crust contains about 5% iron by weight.

A new paper looks at how Earth’s iron diminished over time and how that shaped the development of complex life here on Earth. Is iron necessary for complex life to develop on other worlds?

Continue reading “Life on Earth Needed Iron. Will it be the Same on Other Worlds?”Researchers May Have Found the Missing Piece of Evidence that Explains the Origins of Life

The question of how life first emerged here on Earth is a mystery that continues to

One of the more daunting aspects of the mystery has to do with peptides and enzymes, which fall into something of a “chicken and egg” situation. Addressing this, a team of researchers from the University College London (UCL) recently conducted a study that effectively demonstrated that peptides could have formed in conditions

Language in the Cosmos I: Is Universal Grammar Really Universal?

The METI Symposium

The symposium

How could you devise a message for intelligent creatures from another planet? They wouldn’t know any human language. Their ‘speech’ might be as different from ours as the eerie cries of whales or the twinkling lights of fireflies. Their cultural and scientific history would have followed its own path. Their minds might not even work like ours. Would the deep structure of language, its so called ‘universal grammar’ be the same for aliens as for us? A group of linguists and other scientists gathered on May 26 to discuss the challenging problems posed by devising a message that extraterrestrial beings could understand. There are growing hopes that such beings might be out there among the billions of habitable planets that we now think exist in our galaxy. The symposium, called ‘Language in the Cosmos’ was organized by METI International. It took place as part of the National Space Society’s International Space Development Conference in Los Angeles. The Chair of the workshop was Dr. Sheri Wells-Jensen, a linguist from Bowling Green State University in Ohio.

What is METI International?

‘METI’ stands for messaging to extraterrestrial intelligence. METI International is an organization of scientists and scholars that aims to foster an entirely new approach in our search for alien civilizations. Since 1960, researchers have been looking for extraterrestrials by searching for possible messages they might send to us by radio or laser beams. They have sought the giant megastructures that advanced alien societies might build in space. METI International wants to move beyond this purely passive search strategy. They want to construct and transmit messages to the planets of relatively nearby stars, hoping for a response.

One of the organization’s central goals is to build an interdisciplinary community of scholars concerned with designing interstellar messages that can be understood by non-human minds. More generally, it works internationally to promote research in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence and astrobiology, and to understand the evolution of intelligence here on Earth. The daylong symposium featured eleven presentations. It main theme was the role of linguistics in communication with extraterrestrial intelligence.

This article

This article is the first in a two part series. It will focus on one of the most fundamental issues addressed at the conference. This is the question of whether the deep underlying structure of language would likely be the same for extraterrestrials as for us. Linguists understand the deep structure of language using the theory of ‘universal grammar’. The eminent Linguist Noam Chomsky developed this theory in the middle of the twentieth century.

Two interrelated presentations at the symposium addressed the issue of universal grammar. The first was by Dr. Jeffery Punske of Southern Illinois University and Dr. Bridget Samuels of the University of Southern California. The second was given by Dr. Jeffrey Watumull of Oceanit, whose coauthors were Dr. Ian Roberts of the University of Cambridge, and Dr. Noam Chomsky himself, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Chomsky’s universal grammar-For humans only?

Universal grammar

Despite its name, Chomsky originally took his ‘universal grammar’ theory to imply that there are major, and maybe insuperable barriers to mutual understanding between humans and extraterrestrials. Let’s first consider why Chomsky’s theories seemed to make interstellar communication virtually hopeless. Then we’ll examine why Chomsky’s colleagues who presented at the symposium, and Chomsky himself, now think differently.

Before the second half of the twentieth century, linguists believed that the human mind was a blank slate, and that we learned language entirely by experience. These beliefs dated to the seventeenth century philosopher John Locke and were elaborated in the laboratories of behaviorist psychologists in the early twentieth century. Beginning in the 1950’s, Noam Chomsky challenged this view. He argued that learning a language couldn’t simply be a matter of learning to associate stimuli with responses. He saw that young children, even before the age of 5, can consistently produce and interpret original sentences that they had never heard before. He spoke of a “poverty of the stimulus”. Children couldn’t possibly be exposed to enough examples to learn the rules of language from scratch.

Chomsky posited instead that the human brain contained a “language organ”. This language organ was already pre-organized at birth for the basic rules of language, which he called “universal grammar”. It made human infants primed and ready to learn whatever language they were exposed to using only a limited number of examples. He proposed that the language organ arose in human evolution, maybe as recently of 50,000 years ago. Chomsky’s powerful arguments were accepted by other linguists. He came to be regarded as one of the great linguists and cognitive scientists of the twentieth century.

Universal grammar and ‘Martians’

Human beings speak more than 6000 different languages. Chomsky defined his “universal grammar” as “the system of principles, conditions, and rules that are elements or properties of all human languages”. He said it could be taken to express “the essence of human language”. But he wasn’t convinced that this ‘essence of human language’ was the essence of all theoretically possible languages. When Chomsky was asked by an interviewer from Omni Magazine in 1983 whether he thought that it would be possible for humans to learn an alien language, he replied:

“Not if their language violated the principles of our universal grammar, which, given the myriad ways that languages can be organized, strikes me as highly likely…The same structures that make it possible to learn a human language make it impossible for us to learn a language that violates the principles of universal grammar. If a Martian landed from outer space and spoke a language that violated universal grammar, we simply would not be able to learn that language the way that we learn a human language like English or Swahili. We should have to approach the alien’s language slowly and laboriously — the way that scientists study physics, where it takes generation after generation of labor to gain new understanding and to make significant progress. We’re designed by nature for English, Chinese, and every other possible human language. But we’re not designed to learn perfectly usable languages that violate universal grammar. These languages would simply not be within the range of our abilities.”

If intelligent, language-using life exists on another planet, Chomsky knew, it would necessarily have arisen by a different series of evolutionary changes than the uniquely improbable path that produced human beings. A different history of climate changes, geological events, asteroid and comet impacts, random genetic mutations, and other events would have produced a different set of life forms. These would have interacted with one another in a different ways over the history of life on the planet. The “Martian” language organ, with its different and unique history, could, Chomsky surmised, be entirely different from its human counterpart, making communication monumentally difficult, if not impossible.

Convergent evolution and alien minds

The tree of life

Why did Chomsky think that the human and ‘Martian‘ language organ would likely be fundamentally different? How come he and his colleagues now hold different views? To find out, we first need to explore some basic principles of evolutionary theory.

Originally formulated by the naturalist Charles Darwin in the nineteenth century, the theory of evolution is the central principle of modern biology. It is our best tool for predicting what life might be like on other planets. The theory maintains that living species evolved from previous species. It asserts that all life on Earth is descended from an initial Earthly life form that lived more than 3.8 billion years ago.

You can think of these relationships as like a tree with many branches. The base of the trunk of the tree represents the first life on Earth 3.8 billion years ago. The tip of each branch represents now, and a modern species. The diverging branches connecting each branch tip with the trunk represent the evolutionary history of each species. Each branch point in the tree is where two species diverged from a common ancestor.

Evolution, brains, and contingency

To understand Chomsky’s thinking, we’ll start with a familiar group of animals; the vertebrates, or animals with backbones. This group includes fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, including humans.

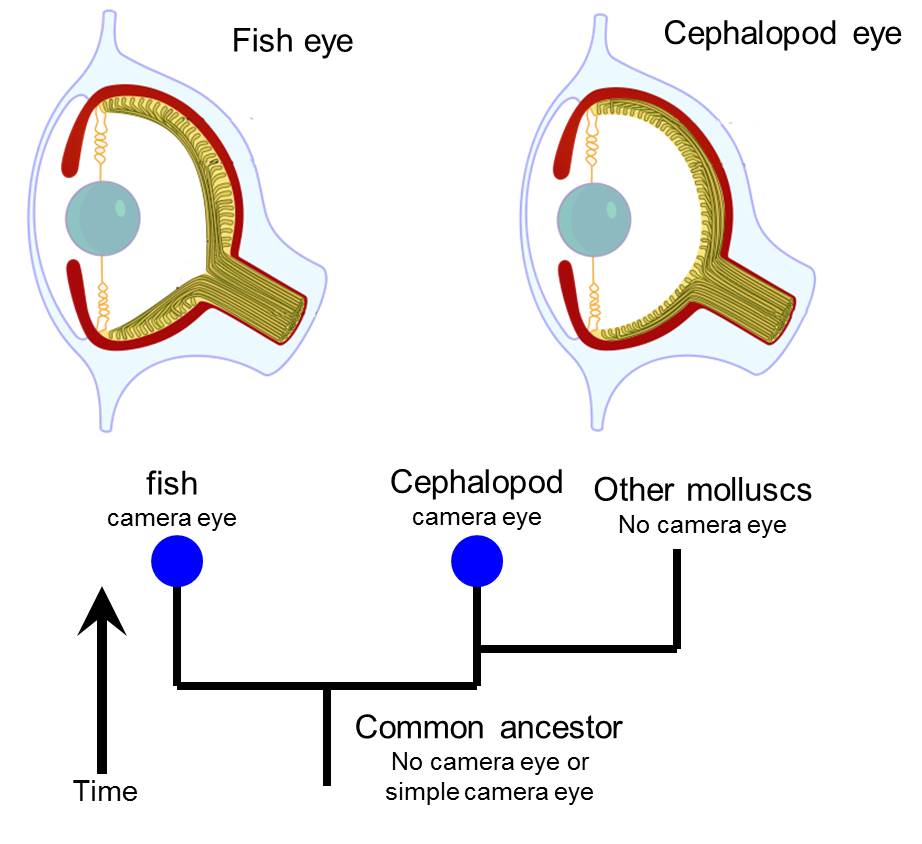

We’ll compare the vertebrates with a less familiar, and distantly related group; the cephalopod molluscs. This group includes octopuses, squids, and cuttlefish. These two groups have been evolving along separate evolutionary paths-different branches of our tree-for more than 600 million years. I’ve chosen them because, as they’ve traveled along their separate branch of our evolutionary tree, each has evolved it own sort of complex brains and complex sense organs.

The brains of all vertebrates have the same basic plan. This is because they all evolved from a common ancestor that already had a brain with that basic plan. The octopus’s brain, by contrast, has an utterly different organization. This is because the common ancestor of cephalopods and vertebrates lies much further back in evolutionary time, on a lower branch of our tree. It probably had only the simplest of brains, if any at all.

With no common plan to inherit, the two kinds of brains evolved independently of one another. They are different because evolutionary change is contingent. That is, it involves varying combinations of influences, including chance. Those contingent influences were different along the path that produced cephalopod brains, than along the one that led to vertebrate brains.

Chomsky believed that many languages might be theoretically possible that violated the seemingly arbitrary constraints of human universal grammar. There didn’t seem to be anything that made our actual universal grammar something special. So, because of the contingent nature of evolution, Chomsky assumed that the ‘Martian’ language organ would arrive at one of these other possibilities, making it fundamentally different from its human counterpart.

This sort of evolution-based pessimism about the likelihood that humans and aliens could communicate is widespread. At the symposium, Dr. Gonzalo Munévar of Lawrence Technological University argued that intelligent creatures that evolved sensory systems and cognitive structures different from ours would not develop similar scientific theories or even similar mathematics.

Evolution, eyes, and convergence

Now lets consider another feature of the octopus and other cephalopods; their eyes. Surprisingly, the eyes of octopuses resemble those of vertebrates in intricate detail. This uncanny resemblance can’t be explained in the same way as the general resemblance of vertebrate brains to one another. It’s almost certainly not due to inheritance of the traits from a common ancestor. It’s true that some of the genes involved in the building of eyes are the same in most animals, appearing far down towards the trunk of our evolutionary tree. But, biologists are almost certain that the common ancestor of cephalopods and vertebrates was much too simple to have any eyes at all.

Biologists think eyes evolved separately more than forty times on Earth, each on its own branch of the evolutionary tree. There are many different kinds of eyes. Some are so strangely different from our own that even a science fiction writer would be surprised by them. So, if evolutionary change is contingent, why do octopus eyes bear a striking and detailed similarity to our own? The answer lies outside of evolutionary theory, with the laws of optics. Many large animals, like the octopus, need acute vision. There is only one good way, under the laws of optics, to make an eye that meets the needed requirements. Whenever such an eye is needed, evolution finds this same best solution. This phenomenon is called convergent evolution.

Life on another planet would have its own separate evolutionary tree, with the base of the trunk representing the appearance of life on that planet. Because of the contingency of evolutionary change, the pattern of branches might be quite different from our Earthly evolutionary tree. But because the laws of optics are the same everywhere in the universe, we can expect that large animals under similar conditions will evolve an eye that looks a lot like that of a vertebrate or a cephalopod. Convergent evolution is potentially a universal phenomenon.

Not just for humans anymore?

Taking apart the language organ

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, Chomsky and some of his colleagues started to look at the language organ and universal grammar in a new way. This new view made it seem like the properties of universal grammar were inevitable, much as the laws of optics made many features of the octopus’s eye inevitable.

In a 2002 review, Chomsky and his colleagues Marc Hauser and Tecumseh Fitch argued that the language organ can be decomposed into a number of distinct parts. The sensory-motor, or externalization, system is involved in the mechanics of expressing language through methods like vocal speech, writing, typing, or sign language. The conceptual-intentional system relates language to concepts.

The core of the system, the trio proposed, consists of what they called the narrow faculty of language. It is a system for applying the rules of language recursively, over and over, thereby allowing the construction of an almost endless range of meaningful utterances. Jeffrey Punske and Bridget Samuels similarly spoke of a ‘syntactic spine’ of all human languages. Syntax is the set of rules that govern the grammatical structure of sentences.

The inevitability of universal grammar

Chomsky and his colleagues made a careful analysis of what computations a nervous system might need to perform in order to make this recursion possible. As an abstract description of how the narrow faculty works, the researchers turned to a mathematical model called the Turing machine. The mathematician Alan Turing developed this model early in the twentieth century. This theoretical ‘machine’ led to the development of electronic computers.

Their analysis led to a striking and unexpected conclusion. In a book chapter currently in press, Watumull and Chomsky write that “Recent work demonstrating the simplicity and optimality of language increases the cogency of a conjecture that at one time would have been summarily dismissed as absurd: the basic principles of language are drawn from the domain of (virtual) conceptual necessity”. Jeffrey Watumull wrote that this strong minimalist thesis posits that “there exist constraints in the structure of the universe itself such that systems cannot but conform”. Our universal grammar is something special, and not just one among many theoretical possibilities.

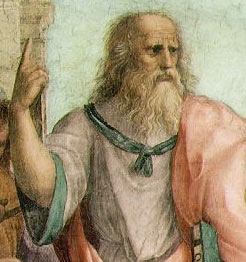

Plato and the strong minimalist thesis

The constraints of mathematical and computational necessity shape the narrow faculty to be as it is, just like the laws of optics shape both the vertebrate and the octopus eye. ‘Martian’ languages, then, might follow the same universal grammar as human languages because there is only one best way to make the recursive core of the language organ.

Through the process of convergent evolution, nature would be compelled to find this one best way wherever and whenever in the universe that language evolves. Watumull supposed that the brain mechanisms of arithmetic might reflect a similarly inevitable convergence. That would mean that the basics of arithmetic would also be the same for humans and aliens. We must, Watumull and Chomsky wrote “rethink any presumptions that extraterrestrial intelligence or artificial intelligence would really be all that different from human intelligence”.

This is the striking conclusion that Watumull, and in a complementary way, Punske and Samuels presented at the symposium. Universal grammar may actually be universal, after all. Watumull compared this thesis to a modern, computer age version of the beliefs of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, who maintained that mathematical and logical relationships are real things that exist in the world apart from us, and are merely discovered by the human mind. As a novel contribution to a difficult ages-old philosophical problem, these new ideas are sure to stir controversy. They illustrate the depth of new knowledge that awaits us as we reach out to other worlds and other minds.

Universal grammar and messages for aliens

What are the consequences of this new way of thinking about the structure of language for practical attempts to create interstellar messages? Watumull thinks the new thinking is a challenge to “the pessimistic relativism of those who think it overwhelmingly likely that terrestrial (i.e. human) intelligence and extraterrestrial intelligence would be (perhaps in principle) mutually unintelligible”. Punske and Samuels agree, and think that “math and physics likely represent the best bet for common concepts that could be used as a starting point”.

Watumull supposes that while the minds of aliens or artificial intelligences may be qualitatively similar to ours, they may differ quantitatively in having bigger memories, or the ability to think much faster than us. He is confident that an alien language would likely include nouns, verbs, and clauses. That means they could probably understand an artificial message containing such things. Such a message, he thinks, might also profitably include the structure and syntax of natural human languages, because this would likely be shared by alien languages.

Punske and Samuels seem more cautious. They note that “There are some linguists who don’t believe nouns and verbs are universal human language categories”. Still, they suspect that “alien languages would be built of discrete meaningful units that can combine into larger meaningful units”. Human speech consists of a linear sequence of words, but, Punske and Samuels note that “Some of the linearity imposed on human language may be due to the constraints of our vocal anatomy, and already starts to break down when we think about signed languages”.

Overall, the findings foster new hope that devising a message comprehensible to extraterrestrials is feasible. In the next installment, we will look at a new example of such a message. It was transmitted in 2017 towards a star 12 light years from our sun.

References and further reading

Allman J. (2000) Evolving Brains, Scientific American Library

Chomsky, N. (2017) The language capacity: Architecture and evolution, Psychonomics Bulletin Review, 24:200-203.

Gliedman J. (1983) Things no amount of learning can teach, Omni Magazine, chomsky.info

Hauser, M. D. , Chomsky, N. , and Fitch W. T. (2002) The faculty of language: What is it, Who has it, and How did it evolve? Science, 298: 1569-1579.

Land, M. F. and Nilsson, D-E. (2002) Animal Eyes, Oxford Animal Biology Series

Noam Chomsky’s theories on language, Study.com

Patton P. E. (2014) Communicating across the cosmos. Part 1: Shouting into the darkness, Part 2: Petabytes from the stars, Part 3: Bridging the vast gulf, Part 4: Quest for a Rosetta Stone, Universe Today.

Patton P. E. (2016) Alien Minds, I. Are extraterrestrial civilizations likely to evolve, II. Do aliens think big brains are sexy too?, III. The octopus’s garden and the country of the blind, Universe Today

Could We Marsiform Ourselves?

As soon as people learn how inhospitable Mars, Venus, and really the entire Solar System are, they want to know how we can fix it. There’s a word for fixing a planet to make it more like Earth: terraforming.

If you want to fix Mars, all you have to do is thicken and warm up its atmosphere to the point that Earth life could survive. You’d need to do the opposite with Venus, cooling it down and reducing the atmospheric pressure.

But it’s hard to wrap your brain around the scale it would take to do such a thing. We’re talking about an incomprehensible amount of atmosphere to try and modify. The atmospheric pressure on the surface of Venus is 90 times the pressure of Earth. It’s carbon dioxide, so you need some chemical, like magnesium or calcium to lock it away. If you can mine, for example, 4 times the mass of asteroid Vesta, it should be possible.

No, from our perspective, that’s practically impossible. In fact, it’s kind of ironic, when you consider the fact that we’re making our own planet less habitable to human civilization every day.

There’s another path to making another world habitable, however, and that’s changing life itself to be more adaptable to surviving on another world.

Instead of terraforming a planet, what if we terraformed ourselves?

Actually, that’s a really bad term. We’d really be changing ourselves to be better adapted to living on Mars. So we’d be Marsiforming ourselves? Venisfying ourselves? Okay, I’ll need to work on the terminology. But you get the gist.

Life, of course, has been evolving and adapting on Earth for at least 4.1 billion years. Pretty much as soon as life could arise on Earth, it did. And those early lifeforms went on to modify and change, adapting to every environment on our planet, from the deepest oceans, to the mountains. From the deserts to the icy tundra.

But in the last few thousand years, we’ve taken a driving role in the evolution of life for the domesticated plants and animals we eat and care for. Your pet dog looks vastly different from the wolf ancestor it evolved from. We’ve increased the yield of corn and wheat, adapted fruit and vegetables, and turned chickens into flightless mobile breast meat.

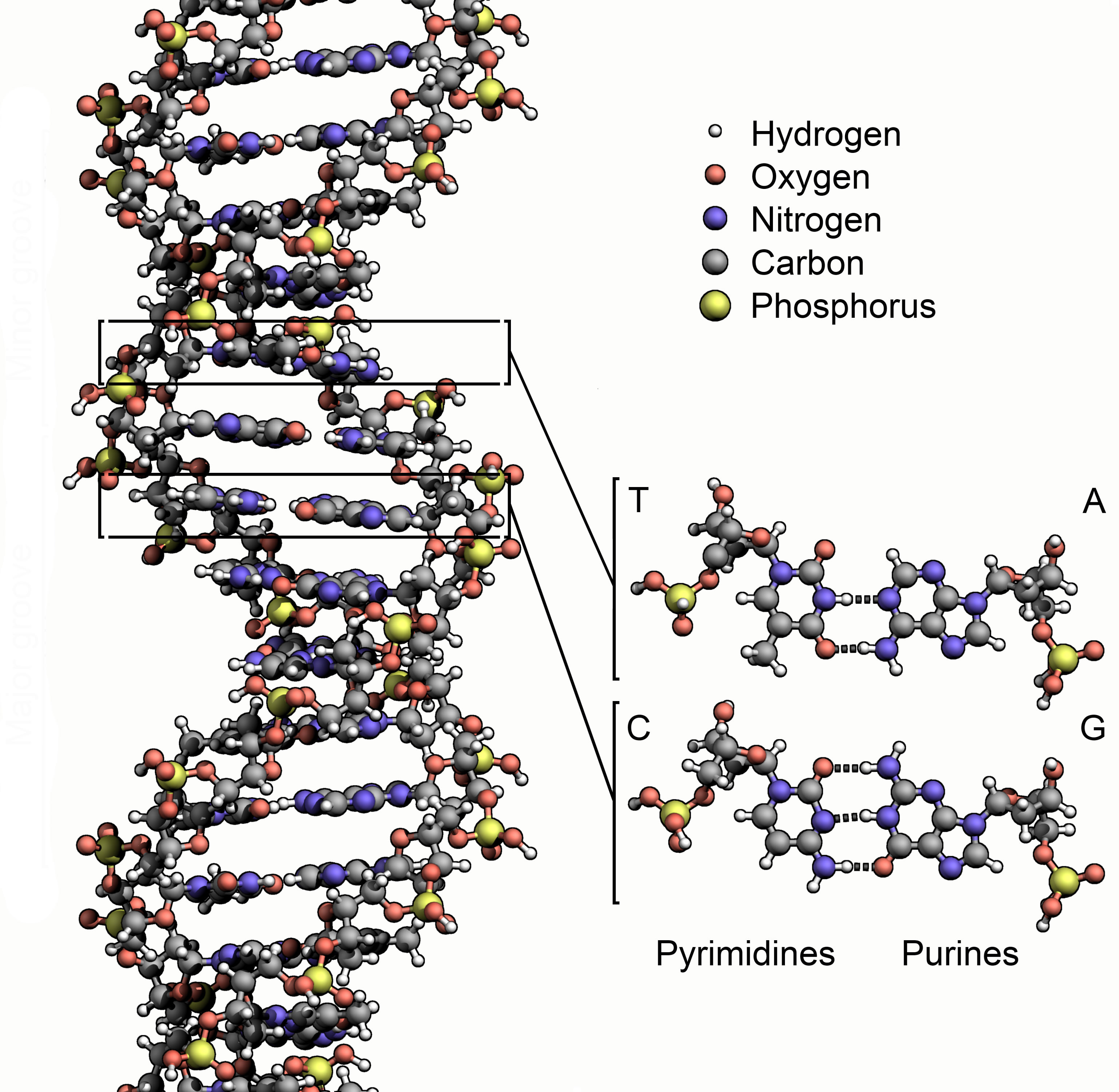

And in the last few decades, we’ve gained the most powerful new tools for adapting life to our needs: genetic modification. Instead of waiting for evolution and selective breeding to get the results we need, we can rewrite the genetic code of lifeforms, borrowing beneficial traits from life over here, and jamming it into the code of life over there. What doesn’t get cooler when it glows in the dark? Nothing, that’s what.

Can we adapt Earth life to live on Mars? It turns out, our toughest life isn’t that far off. During the American Society for Microbiology meeting in 2015, researchers presented how well tough bacteria would be able to handle the conditions on Mars. They found that 4 species of methanogens might actually be able to survive below the surface, consuming hydrogen and carbon dioxide and releasing methane.

In other words, under the right conditions, there are forms of Earth life that can survive on Mars right now. In fact, as we continue to explore Mars, and learn that it’s wetter than we ever thought, we risk infecting the planet with our own microbial life accidentally.

But when we imagine life on Mars, we’re not thinking about a few hardy methanogens, struggling for life beneath the briny regolith. No, we imagine plants, trees, and little animals scurrying about.

Do we have anything close there that we could adapt?

It turns out there are strains of lichen, the symbiosis of fungi and algae that could stand a chance. You’ve probably seen lichen on rocks and other places that suck for any other lifeform. But according to Jean-Pierre de Vera, with the German Aerospace Center’s Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin, Germany, there are Earth-based lichen which are tough enough.

They put lichen into a test environment that simulated the surface of Mars: low atmospheric pressure, carbon dioxide atmosphere, freezing cold temperatures and high radiation. The only things they couldn’t simulate were galactic radiation and low gravity.

In the harshest conditions, the lichen was barely able to hang on and survive, but in milder Mars conditions, protected within rock cracks, the lichen continued to carry out its regular photosynthesis.

It seems that lichen too is ready to go to Mars.

Methanogens and hardy lichen don’t make for the most thrilling forest canopy. In a second, I’m going to talk about what we can do to tweak life to survive and thrive on Mars. But first, I’d like to thank Zach Kanzler, Jeremy Payne, James Craver, Mike Janzen, and the rest of our 709 patrons for their generous support. If you love what we’re doing and want to help out, head over to patreon.com/universetoday.

If our current life isn’t going to get the job done, well then we’re just going to need to adapt it ourselves. Just like we’ve done in the past, with breeding and more recently with rewriting the DNA itself.

Without dramatically changing the environment of Mars to thicken its atmosphere and boost its temperatures, it’s inconceivable to think that we’ll ever adapt anything more complex than bacteria or lichen to survive outside on Mars. But if those give us a toehold, and other techniques can improve the environment, it’s possible to take incremental steps in that direction.

Even within the protected environments of Martian colonies, our current plants and animals probably aren’t up to the task.

The regolith on Mars, for example, contains toxic perchlorates that would kill any Earth-based plants that would try to grow in it. There are Earth-based lifeforms that love perchlorates and it should be possible to create organisms that will strip this toxin out of the regolith and turn it into something useful, like rocket fuel.

Earth-based plants and animals evolved in a 24-hour daily cycle, but a day on Mars is 40 minutes longer than an Earth day. We could grow plants with artificial light, but if we want to use natural Martian light, some adaptation might be required.

Perhaps the biggest risk we face to living on Mars, the one that our technology really can’t help us with is the lower gravity. We don’t know if living in 38% gravity for generations is going to be good for us. We know we can run around on the surface for a few years, but can pregnancy carry to term in this lower gravity?

We just don’t know. In order to find out safely, we’ll need to create rotating space station colonies, where we vary the artificial gravity and see what happens with animals over multiple generations with lower gravity.

If there are health problems, we can take the results of these experiments, and modify genetic code to have better adaptation to this environment. And since humans are animals too, the lessons we learn will help us adapt ourselves to be better prepared to survive on Mars, forever.

Here’s a link to an awesome video from Kurzgesagt about the state of genetic engineering, and the amazing technology that’s just around the corner.

If we are able to change humans to live on Mars, we can probably do the same with other worlds. Image a far future, where human colonies on different worlds are adapted to survive there, using a mixture of technology and genetic manipulation. This will be good and bad. On the good side, human colonies will be able to survive over many generations. On the bad side, they might never be able to live anywhere else in the Solar System without going through the whole adaptation process again.

Would you be willing to change your body permanently to be better adapted to live on another world? Let me know your thoughts in the comments.