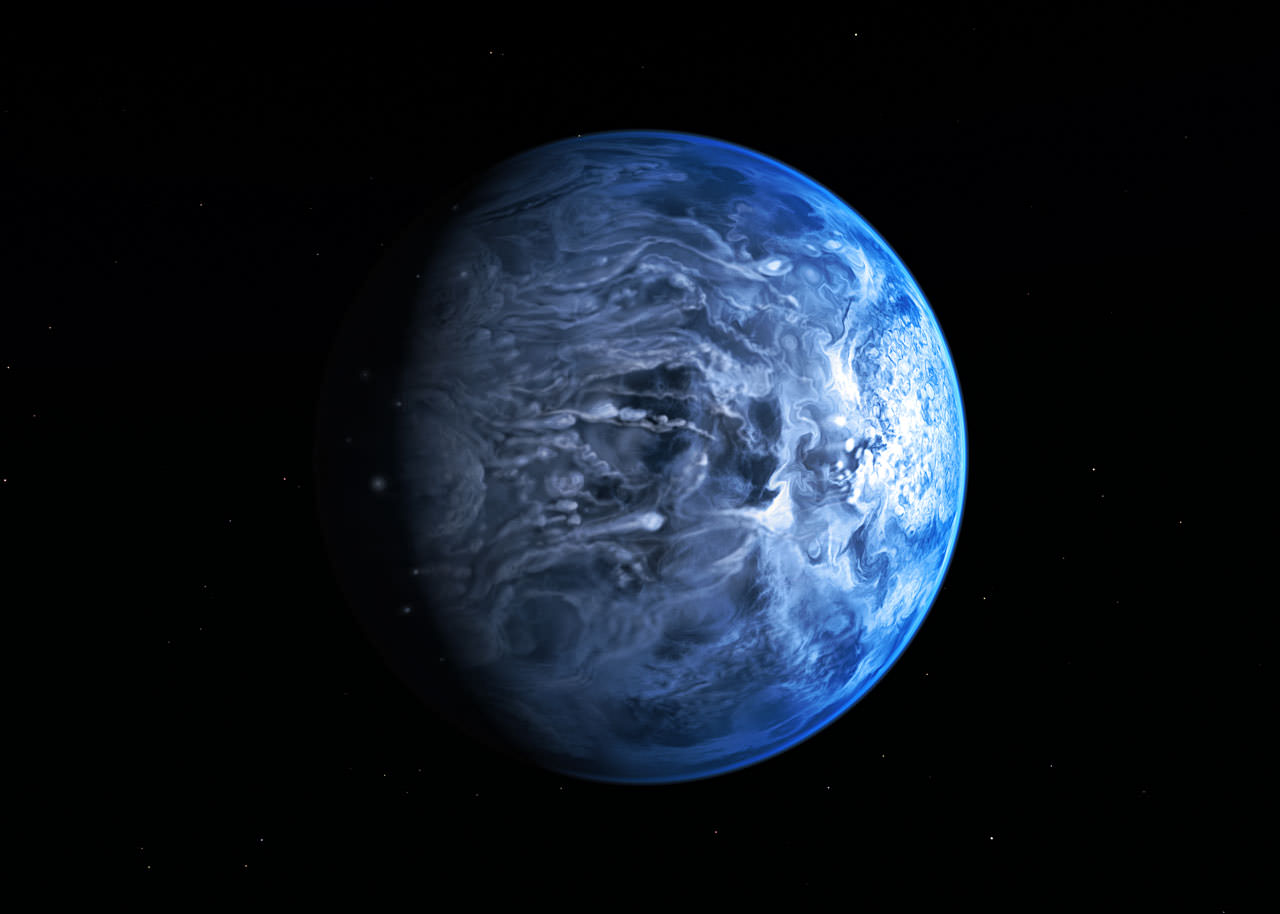

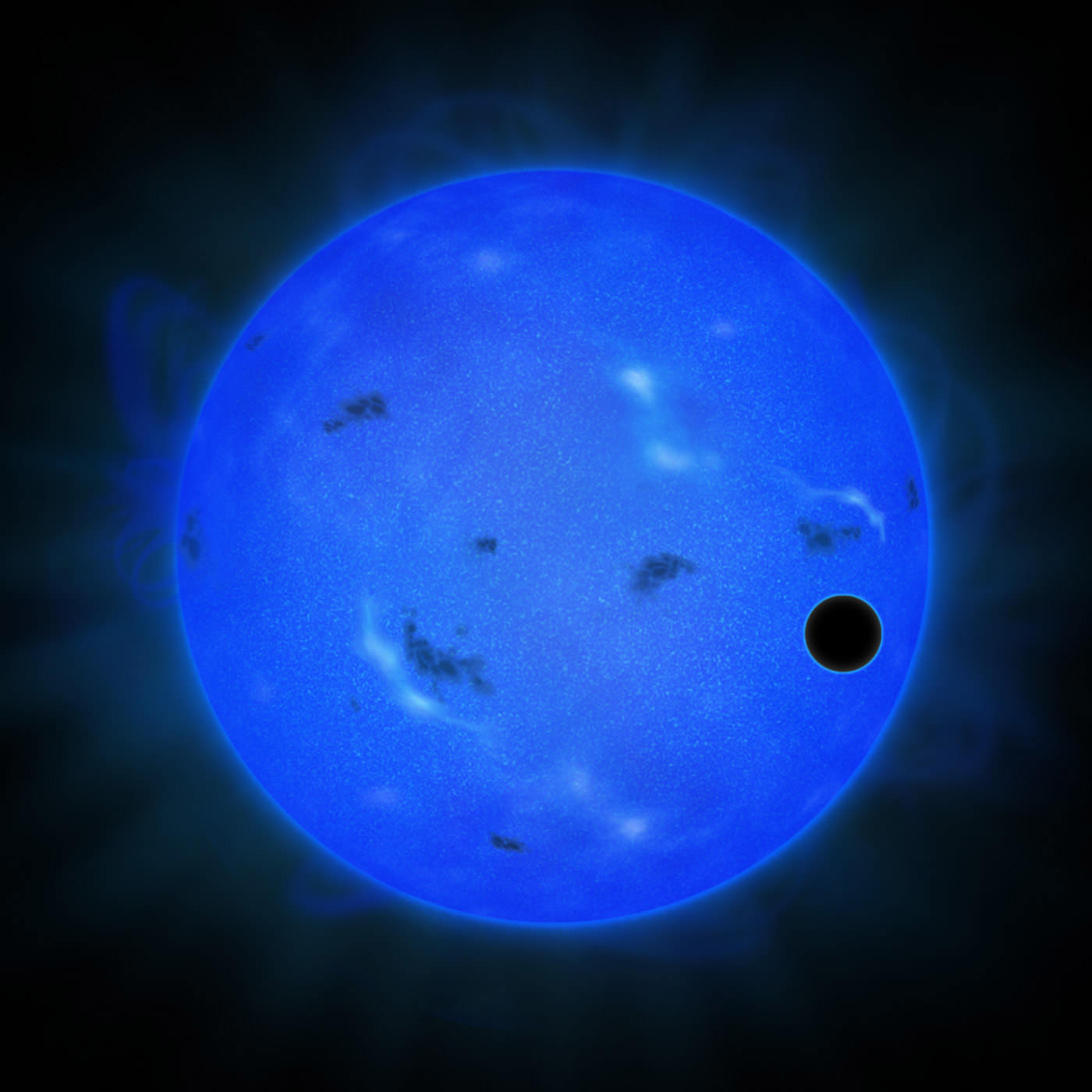

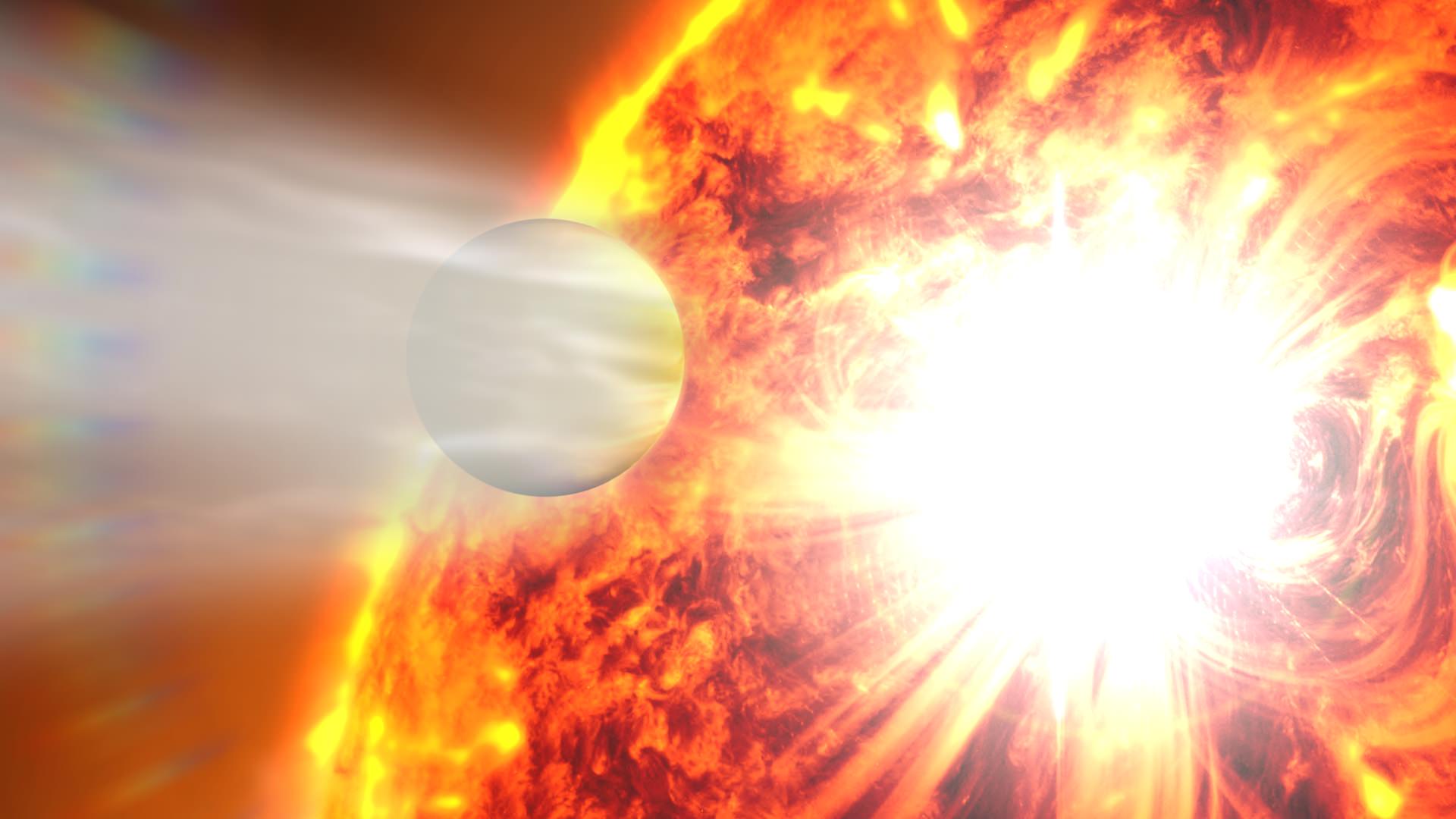

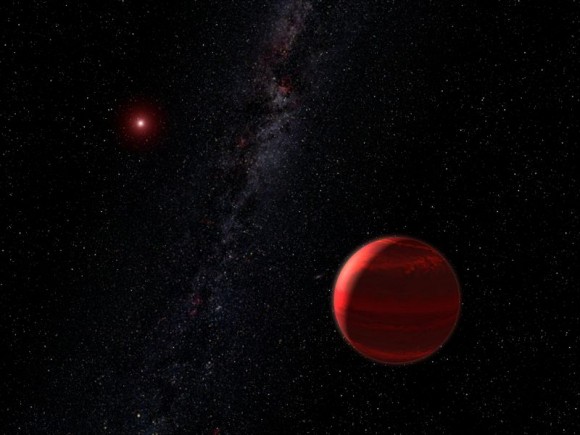

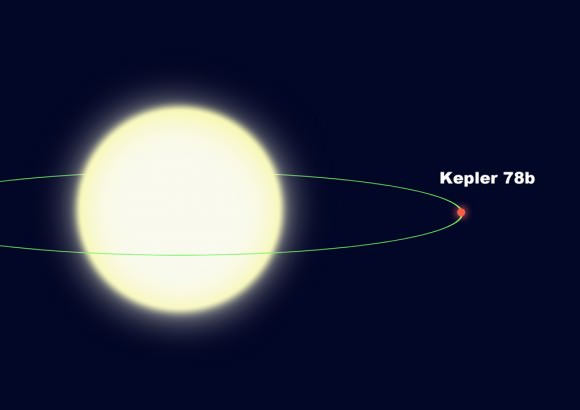

A newly verified planet found in data from the Kepler mission delivers on the space telescope’s task of finding Earth-size planets around other stars. The new planet, called Kepler-78b, is the first Earth-sized exoplanet discovered that has a rocky composition like that of Earth. Similarities to Earth, however, end there. Kepler-78b whizzes around its host star every 8.5 hours at a distance of about 1.5 million kilometers, making it a blazing inferno and not suitable for life as we know it.

“We’ve been hearing about the sungrazing Comet ISON that will go very close to the Sun next month,” said Andrew Howard, of the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s Institute for Astronomy. “Comet ISON will approach the Sun about the same distance that Kepler-78b orbits its star, so this planet spends its entire life as a sungrazer.”

Howard is the lead author on one of two papers published in Nature that details the discovery of the new planet. He spoke during a media webcast discussing the finding.

“This is a planet that exists but shouldn’t,” added astronomer David Latham of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), also discussing the discovery during the webcast.

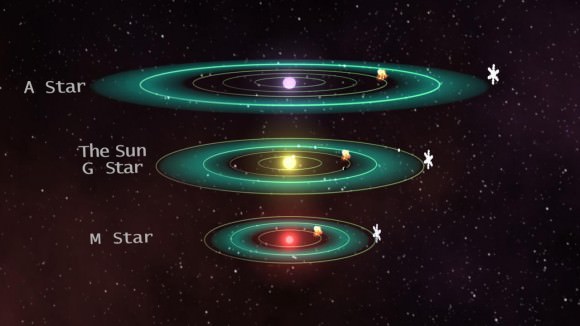

Kepler-78b is 1.2 times the size of Earth with a diameter of 14,800 km (9,200 miles) and 1.7 times more massive. As a result, astronomers say it has a density similar to Earth’s, which suggests an Earth-like composition of iron and rock. A handful of planets the size or mass of Earth have been discovered, but Kepler-78b is the first to have both a measured mass and size. With both quantities known, scientists can calculate a density and determine what the planet is made of.

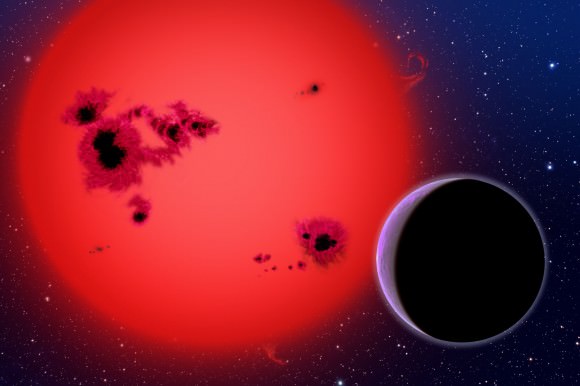

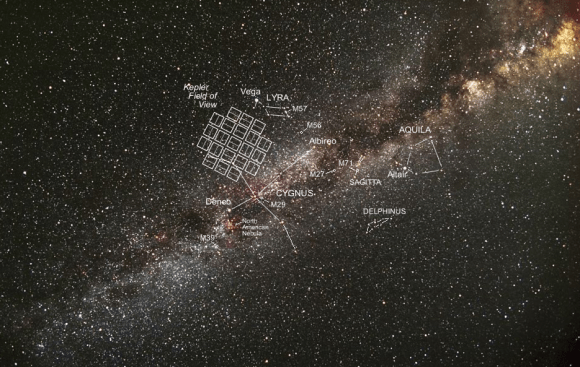

Its star is slightly smaller and less massive than the sun and is located about 400 light-years from Earth in the constellation Cygnus.

However, the close-in orbit of Kepler-78b poses a challenge to theorists. According to current theories of planet formation, it couldn’t have formed so close to its star, nor could it have moved there. Back when this planetary system was forming, the young star was larger than it is now. As a result, the current orbit of Kepler-78b would have been inside the swollen star.

“It couldn’t have formed in place because you can’t form a planet inside a star,” said team member Dimitar Sasselov, also from CfA. “It couldn’t have formed further out and migrated inward, because it would have migrated all the way into the star. This planet is an enigma.”

One idea, suggested Howard, is that the planet is the remnant core of a former gas giant planet, but that turns out to be a problem as well. “We just don’t know what the origin of this planet is,” Howard said.

However, the two teams of planet hunters feel that its existence bodes well for future discoveries of habitable planets.

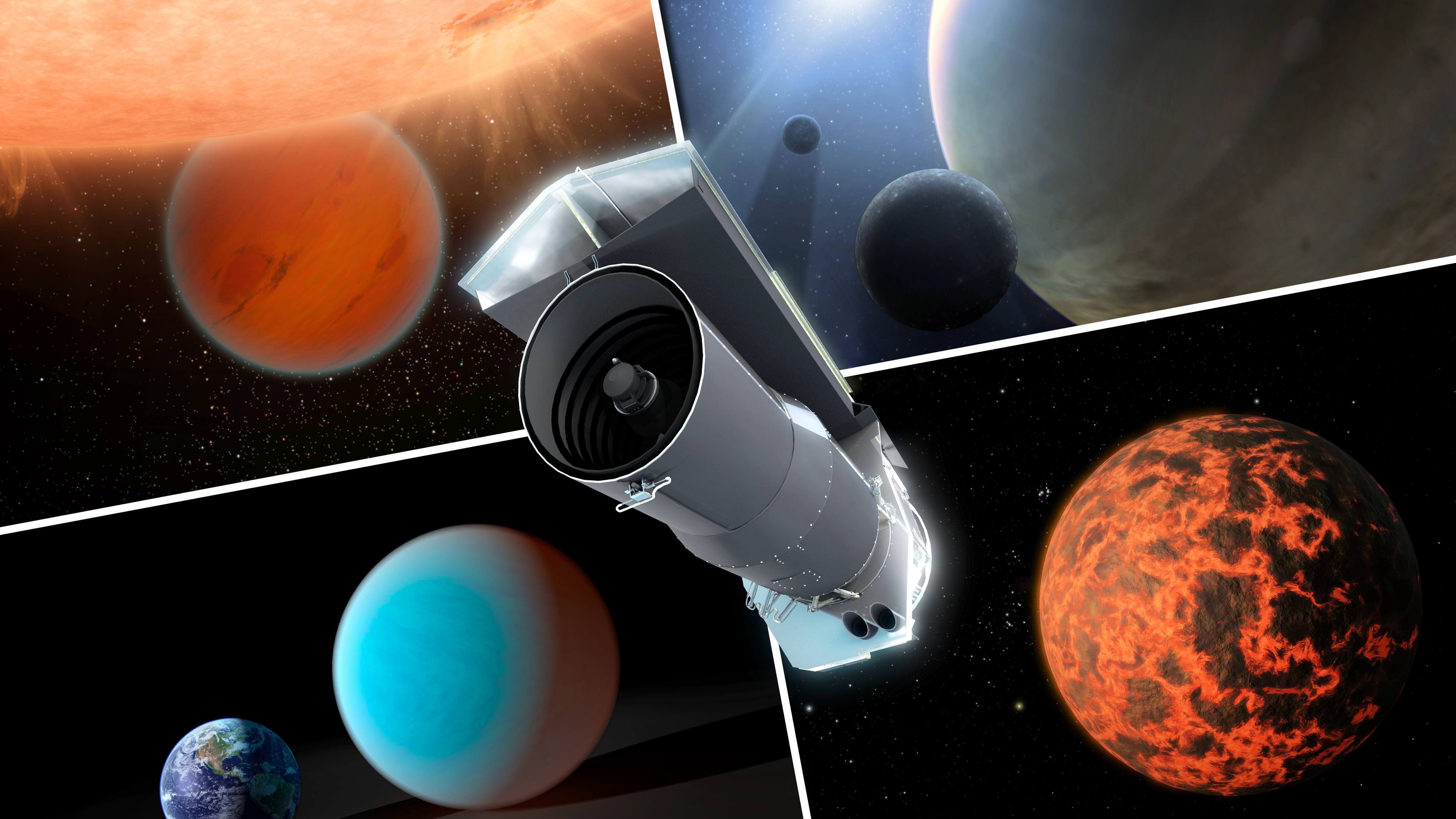

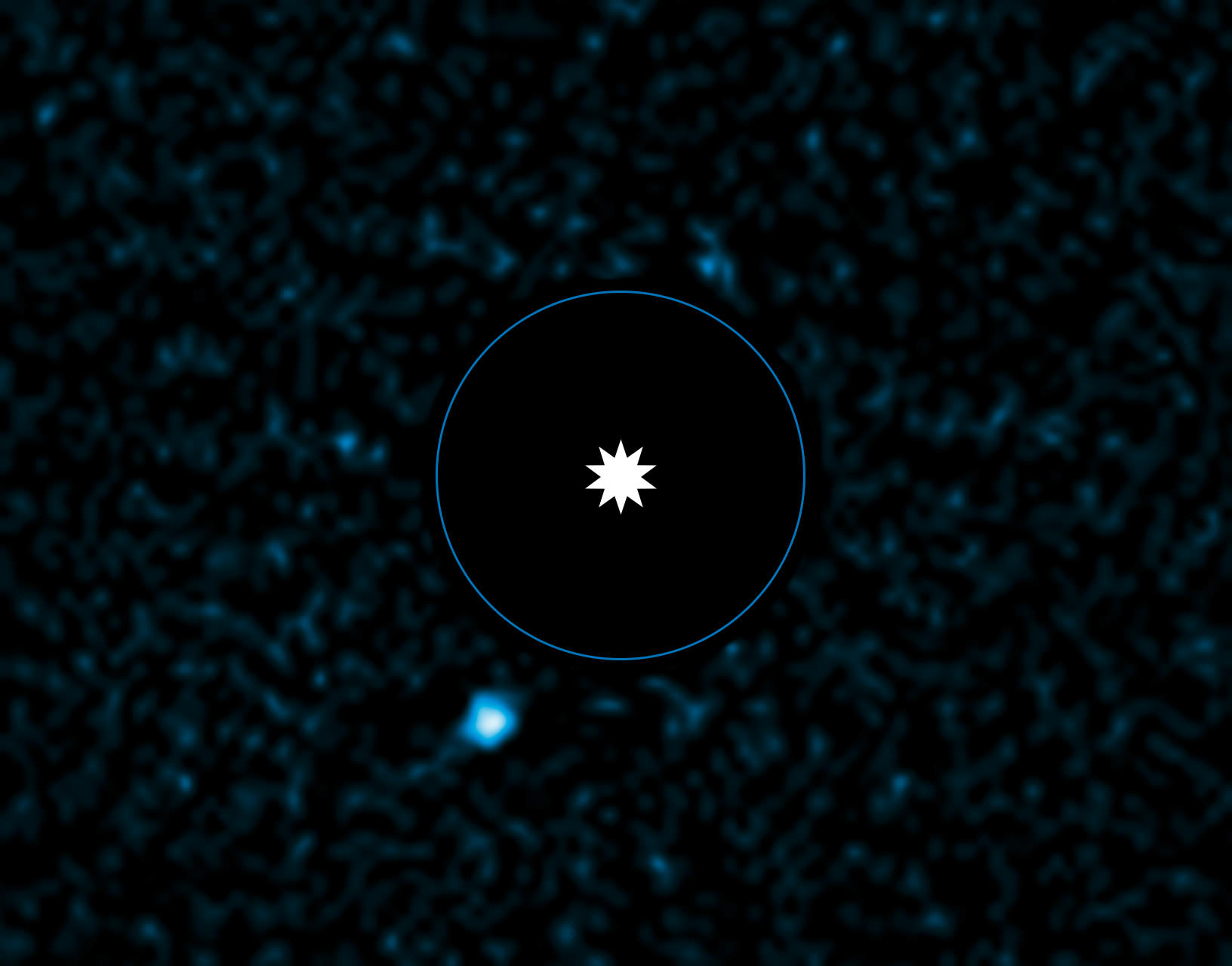

The two independent research teams used ground-based telescopes for follow-up observations to confirm and characterize Kepler-78b. The team led by Howard used the W. M. Keck Observatory atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii. The other team led by Francesco Pepe from the University of Geneva, Switzerland, did their ground-based work at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on La Palma in the Canary Islands.

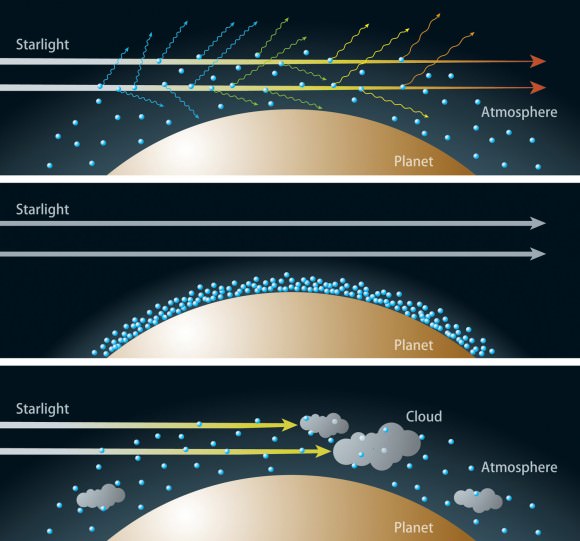

To determine the planet’s mass, the teams employed the radial velocity method to measure how much the gravitation tug of an orbiting planet causes its star to wobble. Kepler, on the other hand, determines the size or radius of a planet by the amount of starlight blocked when it passes in front of its host star.

“Determining mass of an Earth-sized planet is technically daunting,” Howard said during the webcast, explaining how they used the HIRES (High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer) on Keck. “We pushed HIRES to its limit. The observations were difficult because the star is young with many more star spots (just like sunspots on our Sun) than our Sun, and we have to remove them from our data. But since this planet orbits every eight and a half hours, we were able to watch an entire orbit in one night. We clearly saw the planet’s signal, and we watched it eight different nights.”

David Aguilar from CfA said both teams knew the other team was studying this star, but they didn’t compare their work until both teams were ready to submit their papers so that they wouldn’t influence each other. “It was very encouraging both teams got the same result,” Aguilar said.

Howard also thought having two separate teams work on the same target was great. “We didn’t have to wait for further confirmation of the planet, because the two teams confirmed each other,” he said. “In science, this is as good as it gets.”

Francesco Pepe from the second team said they benefitted from using a twin of the original HARPS (High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher) which has found nearly 200 exoplanets. “HARPS North at La Palma has the same precision and efficiency as its twin,” Pepe explained during the webcast, “and we decided to guarantee time to follow up on small exoplanet candidates from Kepler. We optimized our observing strategy and we expect many more confirmations in the coming years from this technique.”

As for Kepler-78b, this is a doomed world. Gravitational tides will continue to pull Kepler-78b even closer to its star. Eventually it will move so close that the star’s gravity will rip the world apart. Theorists predict that the planet will vanish within three billion years. Interestingly, astronomers say, our solar system could have held a planet like Kepler-78b. If it had, the planet would have been destroyed long ago leaving no signs for astronomers today.

“We did not detect additional planets in this system,” said Howard, “but we hope to observe this system more in the future.”

Paper by Howard et al.: A Rocky Composition for an Earth-sized Exoplanet

Paper by Pepe et al.: An Earth-sized planet with an Earth-like density