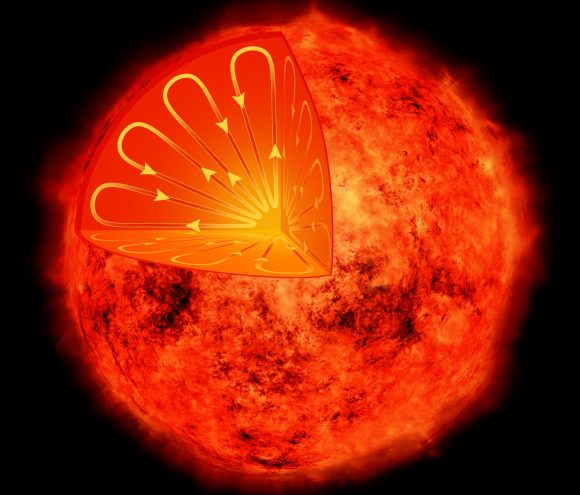

When it comes to how and where planetary systems form, astronomers thought they had a pretty good handle on things. The predominant theory, known as the Nebular Hypothesis, states that stars and planets form from massive clouds of dust and gas (i.e. nebulae). Once this cloud experiences gravitational collapse at the center, its remaining dust and gas forms a protoplanetary disk that eventually accretes to form planets.

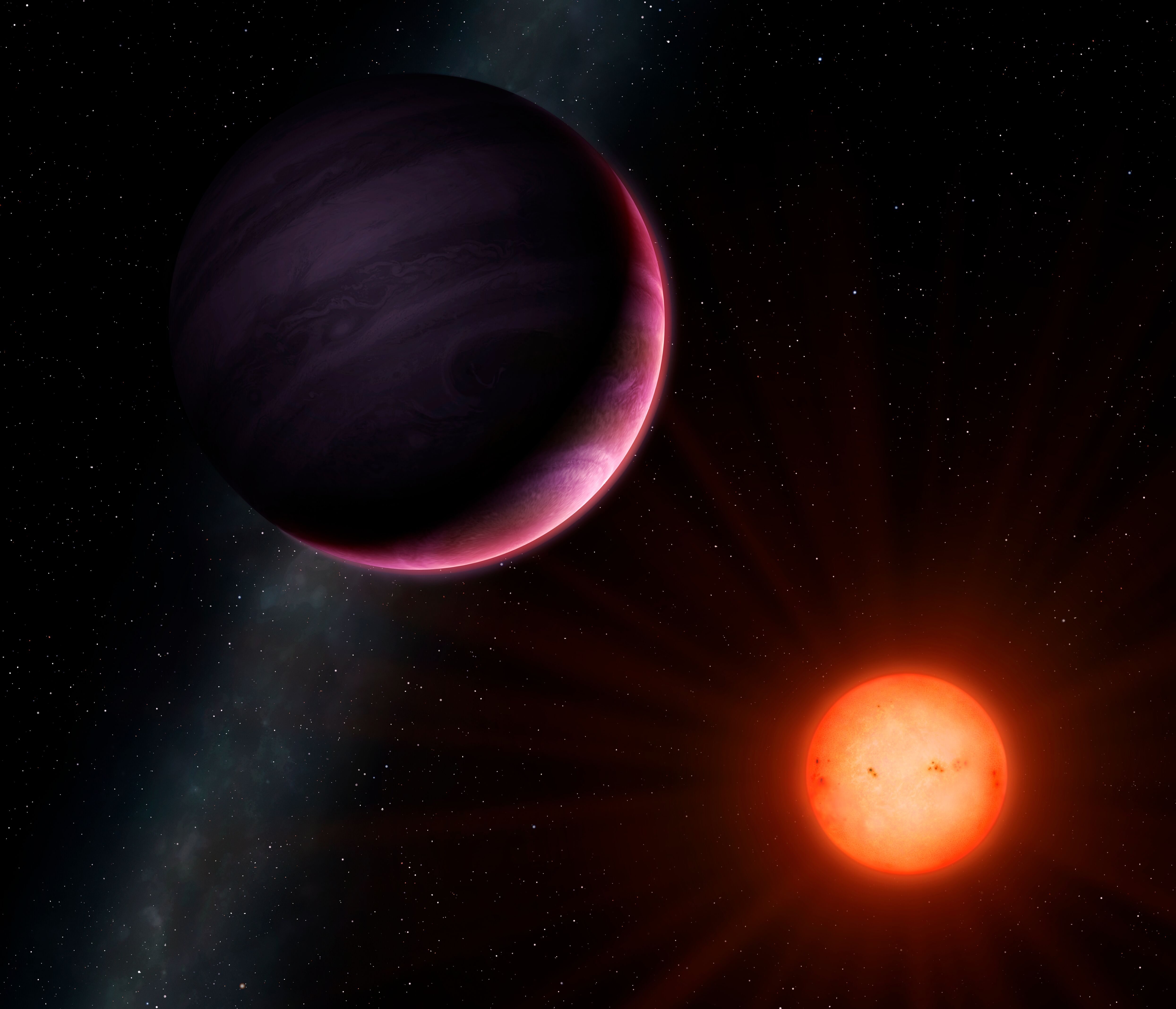

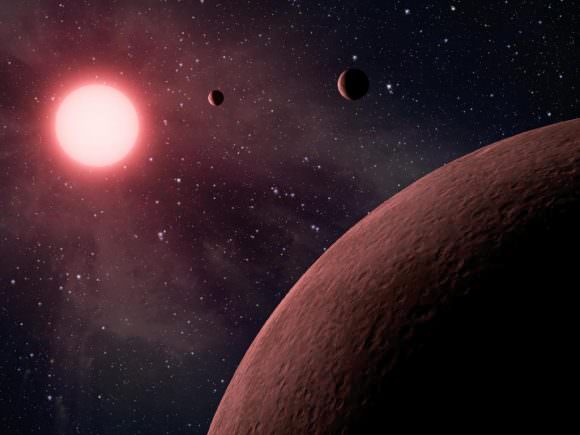

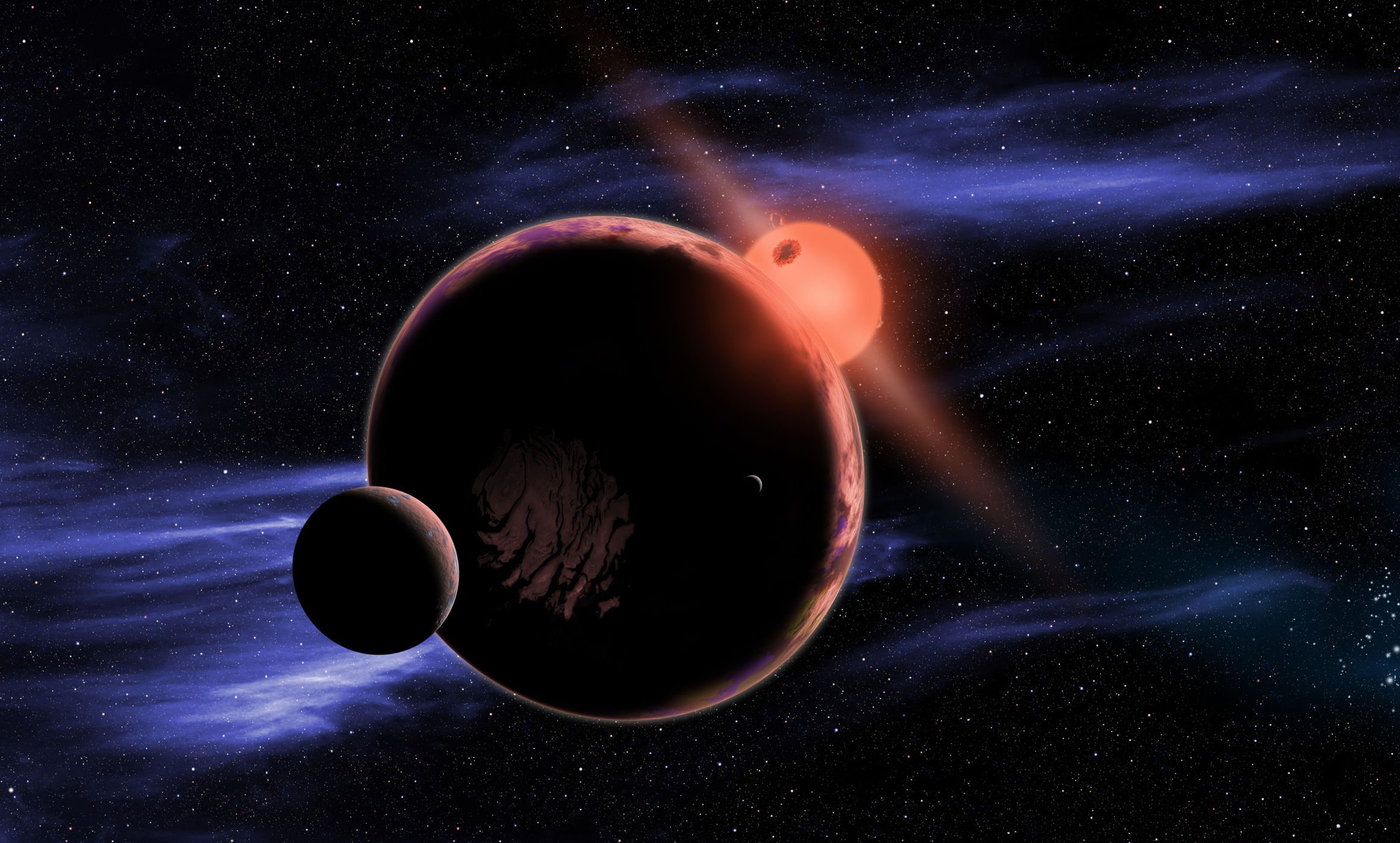

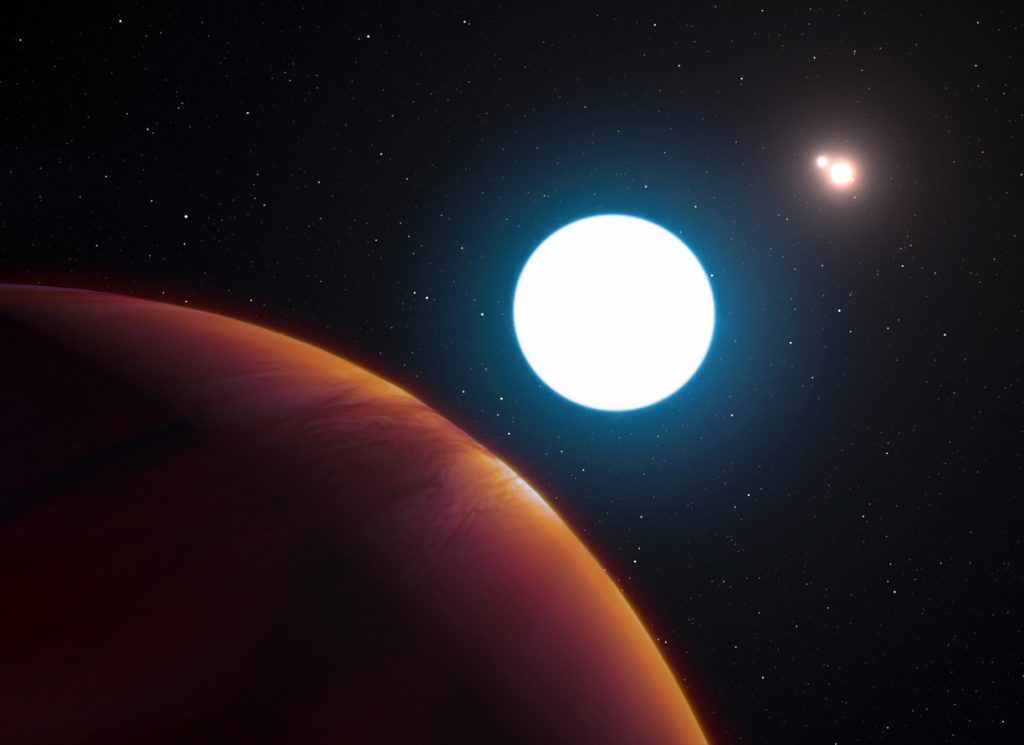

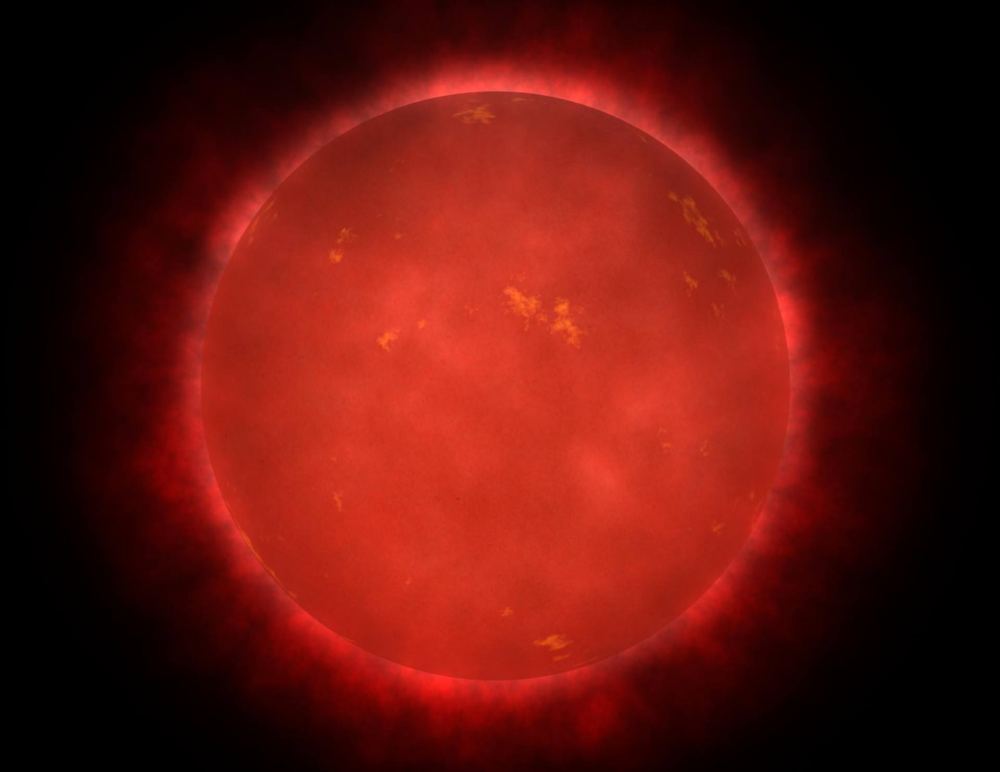

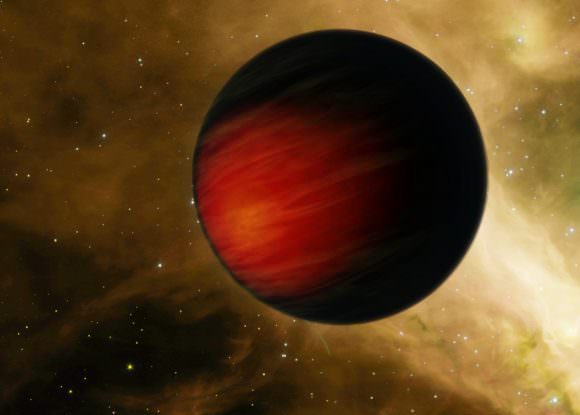

However, when studying the distant star NGTS-1 – an M-type (red dwarf) located about 600 light-years away – an international team led by astronomers from the University of Warwick discovered a massive “hot Jupiter” that appeared far too large to be orbiting such a small star. The discovery of this “monster planet” has naturally challenged some previously-held notions about planetary formation.

The study, titled “NGTS-1b: A hot Jupiter transiting an M-dwarf“, recently appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The team was led by Dr Daniel Bayliss and Professor Peter Wheatley from the University of Warwick and included members from the of the Geneva Observatory, the Cavendish Laboratory, the German Aerospace Center, the Leicester Institute of Space and Earth Observation, the TU Berlin Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics, and multiple universities and research institutes.

The discovery was made using data obtained by the ESO’s Next-Generation Transit Survey (NGTS) facility, which is located at the Paranal Observatory in Chile. This facility is run by an international consortium of astronomers who come from the Universities of Warwick, Leicester, Cambridge, Queen’s University Belfast, the Geneva Observatory, the German Aerospace Center, and the University of Chile.

Using a full array of fully-robotic compact telescopes, this photometric survey is one of several projects meant to compliment the Kepler Space Telescope. Like Kepler, it monitors distant stars for signs of sudden dips in brightness, which are an indication of a planet passing in front of (aka. “transiting”) the star, relative to the observer. When examining data obtained from NGTS-1, the first star to be found by the survey, they made a surprising discovery.

Based on the signal produced by its exoplanet (NGTS-1b), they determined that it was a gas giant roughly the same size as Jupiter and almost as massive (0.812 Jupiter masses). Its orbital period of 2.6 days also indicated that it orbits very close to its star – about 0.0326 AU – which makes it a “hot Jupiter”. Based on these parameters, the team also estimated that NGTS-1b experiences temperatures of approximately 800 K (530°C; 986 °F).

The discovery threw the team for a loop, as it was believed to be impossible for planets of this size to form around small, M-type stars. In accordance with current theories about planet formation, red dwarf stars are believed to be able to form rocky planets – as evidenced by the many that have been discovered around red dwarfs of late – but are unable to gather enough material to create Jupiter-sized planets.

As Dr. Daniel Bayliss, an astronomer with the University of Geneva and the lead-author on the paper, commented in University of Warwick press release:

“The discovery of NGTS-1b was a complete surprise to us – such massive planets were not thought to exist around such small stars. This is the first exoplanet we have found with our new NGTS facility and we are already challenging the received wisdom of how planets form. Our challenge is to now find out how common these types of planets are in the Galaxy, and with the new NGTS facility we are well-placed to do just that.”

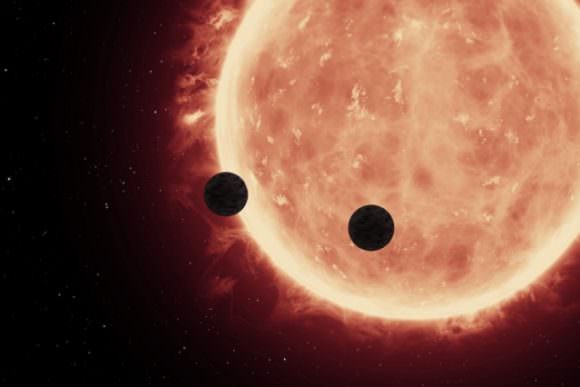

What is also impressive is the fact that the astronomers noticed the transit at all. Compared to other classes of stars, M-type stars are the smallest, coolest and dimmest. In the past, rocky bodies have been detected around them by measuring shifts in their position relative to Earth (aka. the Radial Velocity Method). These shifts are caused by the gravitational tug of one or more planets that cause the planet to “wobble” back and forth.

In short, the low light of an M-type star has made monitoring them for dips in brightness (aka. the Transit Method) highly impractical. However, using the NGTS’s red-sensitive cameras, the team was able to monitored patches of the night sky for many months. Over time, they noticed dips coming from NGTS-1 every 2.6 days, which indicated that a planet with a short orbital period was periodically passing in front of it.

They then tracked the planet’s orbit around the star and combined the transit data with Radial Velocity measurements to determine its size, position and mass. As Professor Peter Wheatley (who leads NGTS) indicated, finding the planet was painstaking work. But in the end, its discovery could lead to the detection of many more gas giants around low-mass stars:

“NGTS-1b was difficult to find, despite being a monster of a planet, because its parent star is small and faint. Small stars are actually the most common in the universe, so it is possible that there are many of these giant planets waiting to found. Having worked for almost a decade to develop the NGTS telescope array, it is thrilling to see it picking out new and unexpected types of planets. I’m looking forward to seeing what other kinds of exciting new planets we can turn up.”

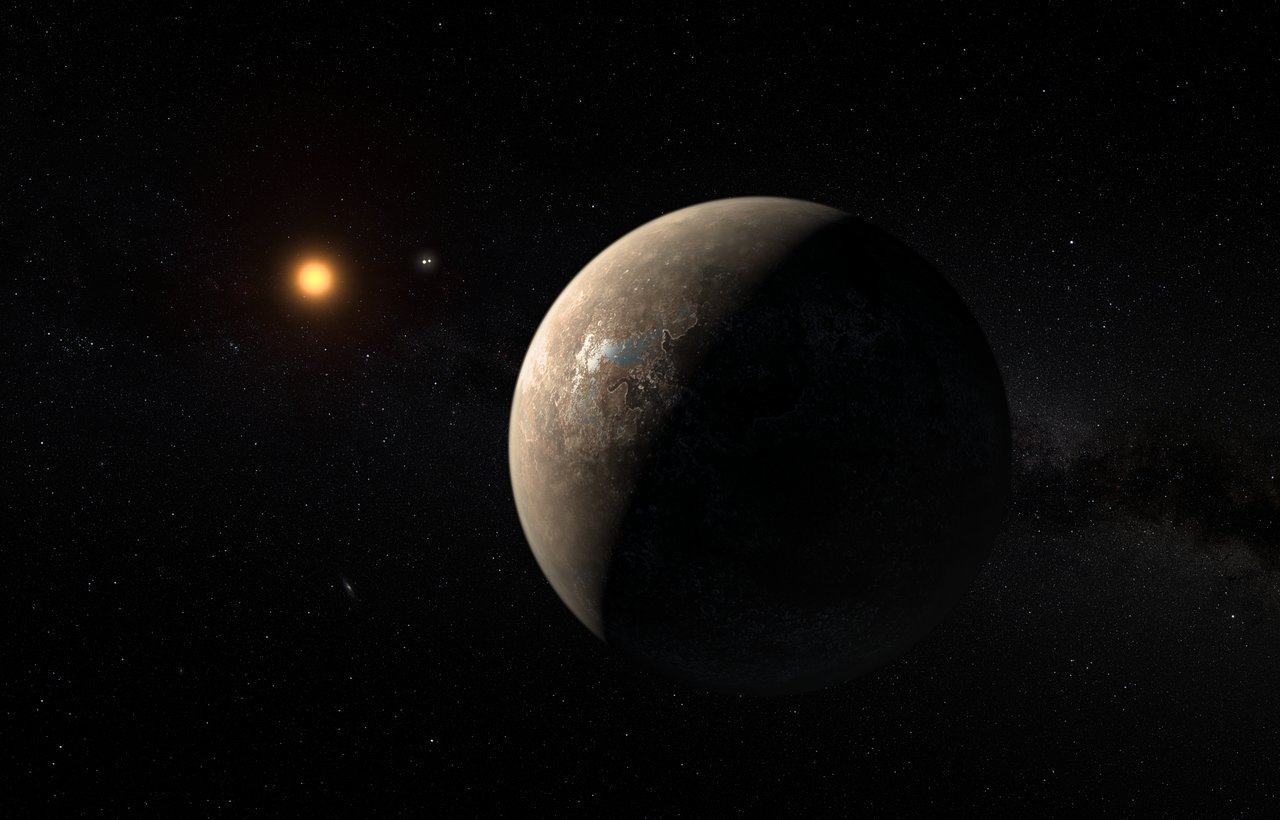

Within the known Universe, M-type stars are by far the most common, accounting for 75% of all stars in the Milky Way Galaxy alone. In the past, the discovery of rocky bodies around stars like Proxima Centauri, LHS 1140, GJ 625, and the seven rocky planets around TRAPPIST-1, led many in the astronomical community to conclude that red dwarf stars were the best place to look for Earth-like planets.

The discovery of a Hot Jupiter orbiting NGTS-1 is therefore seen as an indication that other red dwarf stars could have orbiting gas giants as well. Above all, this latest find once again demonstrates the importance of exoplanet research. With every find we make beyond our Solar System, the more we learn about the ways in which planets form and evolve.

Every discovery we make also advances our understanding of how likely we may be to discover life out there somewhere. For in the end, what greater scientific goal is there than determining whether or not we are alone in the Universe?

Further Reading: UofWarwick, RAS, MNRAS