Welcome back to the latest installment in our series on Exoplanet-hunting methods. Today we begin with the very difficult, but very promising method known as Direct Imaging.

In the past few decades, the number of planets discovered beyond our Solar System has grown by leaps and bounds. As of October 4th, 2018, a total of 3,869 exoplanets have been confirmed in 2,887 planetary systems, with 638 systems hosting multiple planets. Unfortunately, due to the limitations astronomers have been forced to contend with, the vast majority of these have been detected using indirect methods.

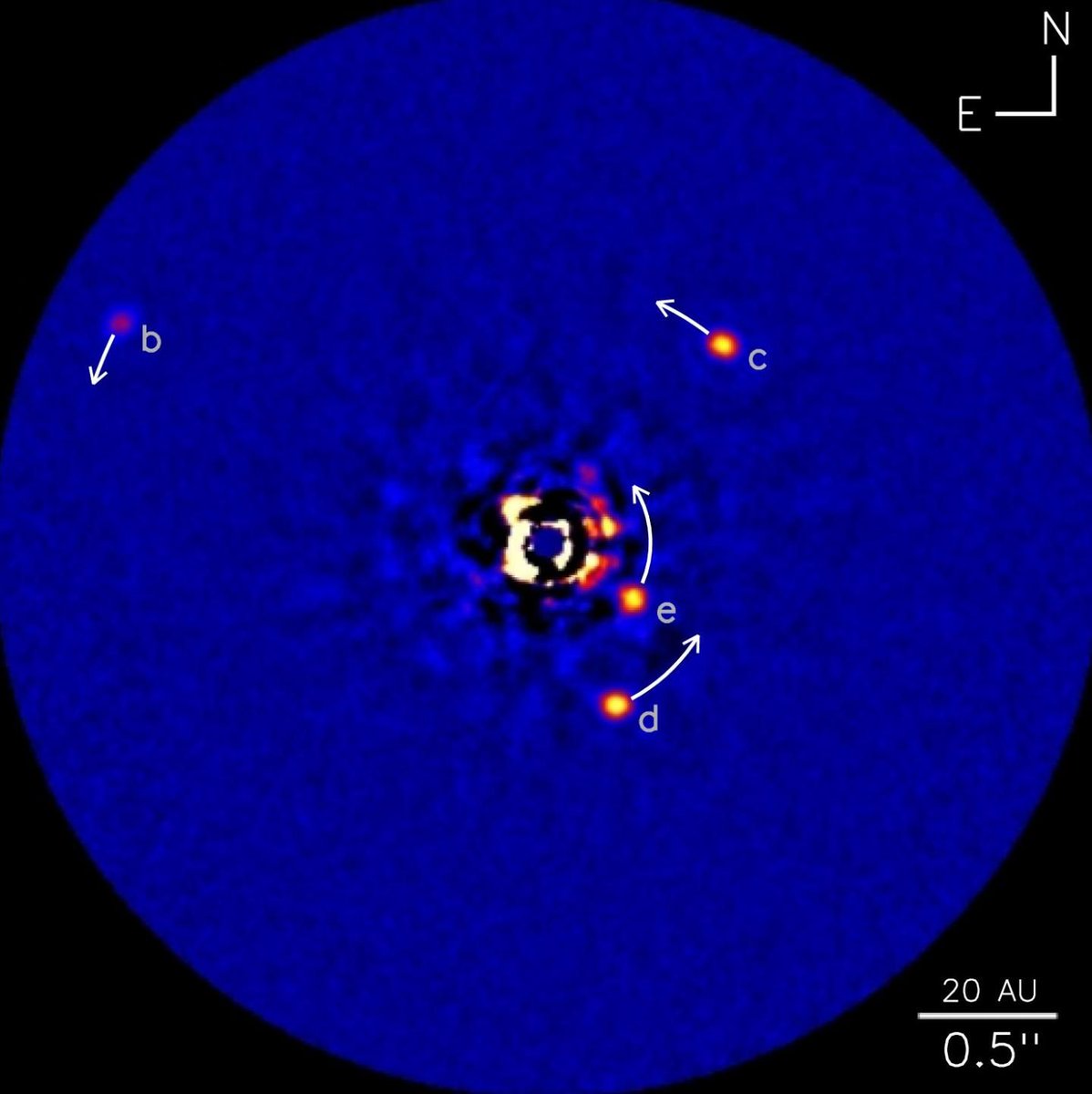

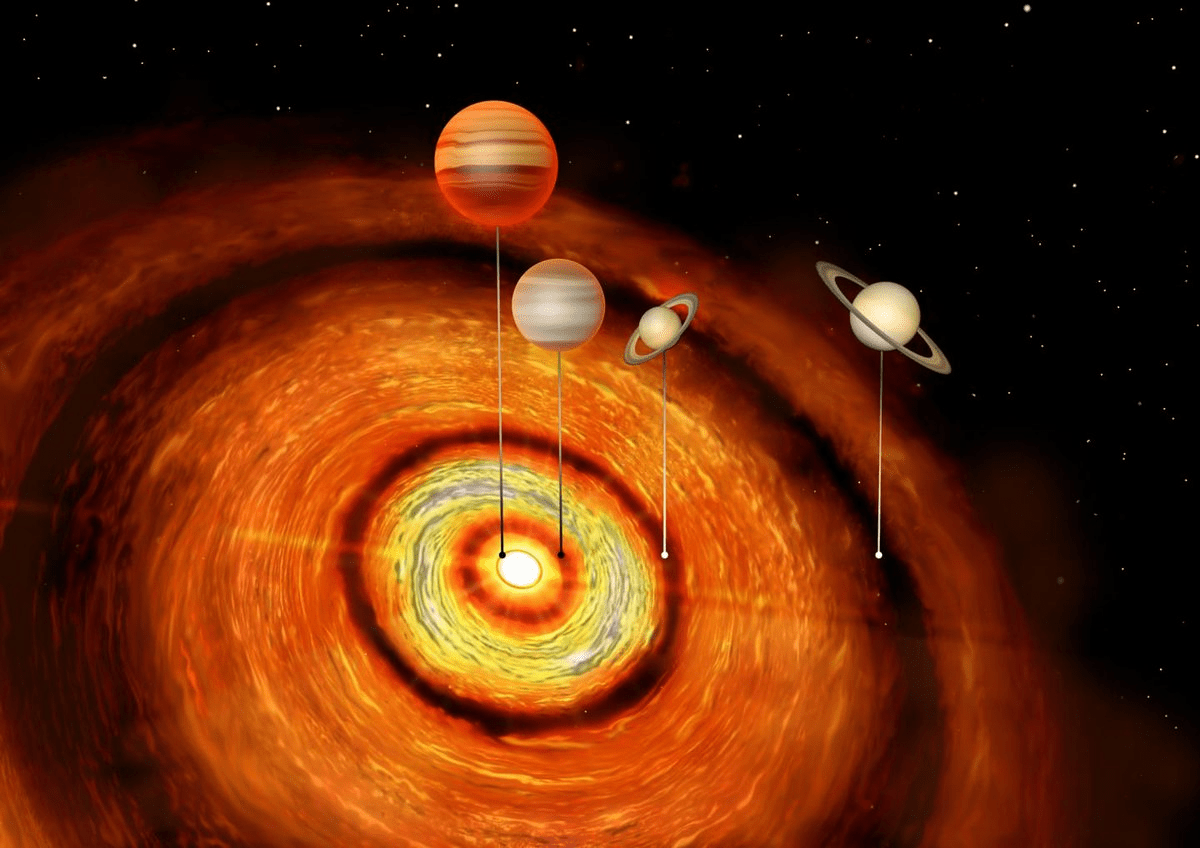

So far, only a handful of planets have been discovered by being imaged as they orbited their stars (aka. Direct Imaging). While challenging compared to indirect methods, this method is the most promising when it comes to characterizing the atmospheres of exoplanets. So far, 100 planets have been confirmed in 82 planetary systems using this method, and many more are expected to be found in the near future.

Continue reading “What is the Direct Imaging Method?”