Beyond our Solar System’s “Frost Line” – the region where volatiles like water, ammonia and methane begin to freeze – four massive planets reside. Though these planets – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – vary in terms of size, mass, and composition, they all share certain characteristics that cause them to differ greatly from the terrestrial planets located in the inner Solar System.

Officially designated as gas (and/or ice) giants, these worlds also go by the name of “Jovian planets”. Used interchangeably with terms like gas giant and giant planet, the name describes worlds that are essentially “Jupiter-like”. And while the Solar System contains four such planets, extra-solar surveys have discovered hundreds of Jovian planets, and that’s just so far…

Definition:

The term Jovian is derived from Jupiter, the largest of the Outer Planets and the first to be observed using a telescope – by Galileo Galilei in 1610. Taking its name from the Roman king of the gods – Jupiter, or Jove – the adjective Jovian has come to mean anything associated with Jupiter; and by extension, a Jupiter-like planet.

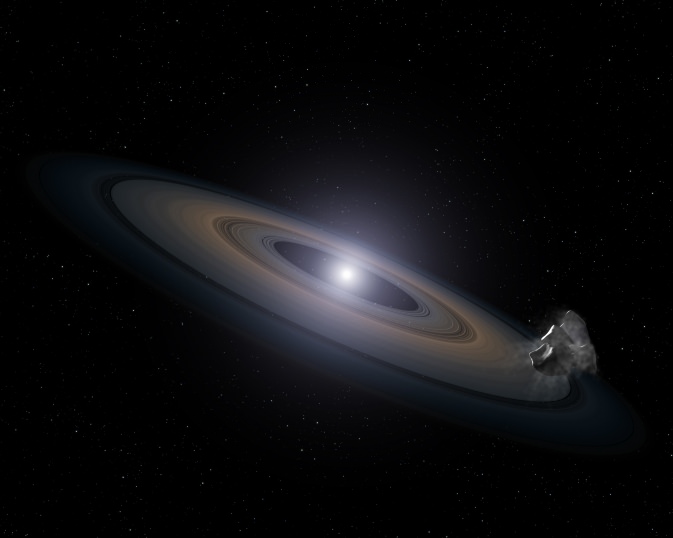

Within the Solar System, four Jovian planets exist – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. A planet designated as Jovian is hence a gas giant, composed primarily of hydrogen and helium gas with varying degrees of heavier elements. In addition to having large systems of moons, these planets each have their own ring systems as well.

Another common feature of gas giants is their lack of a surface, at least when compared to terrestrial planets. In all cases, scientists define the “surface” of a gas giant (for the sake of defining temperatures and air pressure) as being the region where the atmospheric pressure exceeds one bar (the pressure found on Earth at sea level).

Structure and Composition:

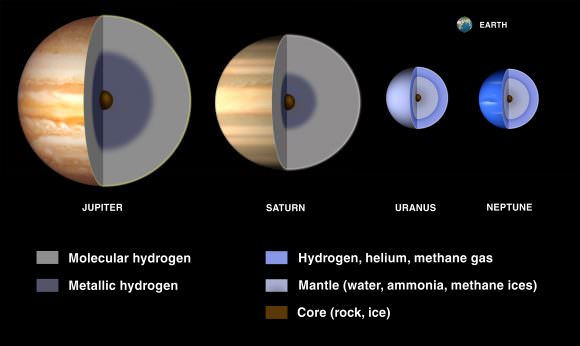

In all cases, the gas giants of our Solar System are composed primarily of hydrogen and helium with the remainder being taken up by heavier elements. These elements correspond to a structure that is differentiated between an outer layer of molecular hydrogen and helium that surrounds a layer of liquid (or metallic) hydrogen or volatile elements, and a probable molten core with a rocky composition.

Due to difference in their structure and composition, the four gas giants are often differentiated, with Jupiter and Saturn being classified as “gas giants” while Uranus and Neptune are “ice giants”. This is due to the fact that Neptune and Uranus have higher concentrations of methane and heavier elements – like oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur – in their interior.

In stark contrast to the terrestrial planets, the density of the gas giants is slightly greater than that of water (1 g/cm³). The one exception to this is Saturn, where the mean density is actually lower than water (0.687 g/cm3). In all cases, temperature and pressure increase dramatically the closer one ventures into the core.

Atmospheric Conditions:

Much like their structures and compositions, the atmospheres and weather patterns of the four gas/ice giants are quite similar. The primary difference is that the atmospheres get progressively cooler the farther away they are from Sun. As a result, each Jovian planet has distinct cloud layers who’s altitudes are determined by their temperatures, such that the gases can condense into liquid and solid states.

In short, since Saturn is colder than Jupiter at any particular altitude, its cloud layers occur deeper within it’s atmosphere. Uranus and Neptune, due to their even lower temperatures, are able to hold condensed methane in their very cold tropospheres, whereas Jupiter and Saturn cannot.

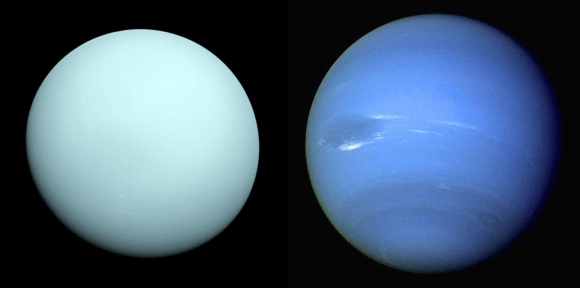

The presence of this methane is what gives Uranus and Neptune their hazy blue color, where Jupiter is orange-white in appearance due to the intermingling of hydrogen (which gives off a red appearance), while the upwelling of phosphorus, sulfur, and hydrocarbons yield spotted patches areas and ammonia crystals create white bands.

The atmosphere of Jupiter is classified into four layers based on increasing altitude: the troposphere, stratosphere, thermosphere and exosphere. Temperature and pressure increase with depth, which leads to rising convection cells emerging that carry with them the phosphorus, sulfur, and hydrocarbons that interact with UV radiation to give the upper atmosphere its spotted appearance.

Saturn’s atmosphere is similar in composition to Jupiter’s. Hence why it is similarly colored, though its bands are much fainter and are much wider near the equator (resulting in a pale gold color). As with Jupiter’s cloud layers, they are divided into the upper and lower layers, which vary in composition based on depth and pressure. Both planets also have clouds composed of ammonia crystals in their upper atmospheres, with a possible thin layer of water clouds underlying them.

Uranus’ atmosphere can be divided into three sections – the innermost stratosphere, the troposphere, and the outer thermosphere. The troposphere is the densest layer, and also happens to be the coldest in the solar system. Within the troposphere are layers of clouds, with methane clouds on top, ammonium hydrosulfide clouds, ammonia and hydrogen sulfide clouds, and water clouds at the lowest pressures.

Next is the stratosphere, which contains ethane smog, acetylene and methane, and these hazes help warm this layer of the atmosphere. Here, temperatures increase considerably, largely due to solar radiation. The outermost layer (the thermosphere and corona) has a uniform temperature of 800-850 (577 °C/1,070 °F), though scientists are unsure as to the reason.

This is something that Uranus shares with Neptune, which also experiences unusually high temperatures in its thermosphere (about 750 K (476.85 °C/890 °F). Like Uranus, Neptune is too far from the Sun for this heat to be generated through the absorption of ultraviolet radiation, which means another heating mechanism is involved.

Neptune’s atmosphere is also predominantly hydrogen and helium, with a small amount of methane. The presence of methane is part of what gives Neptune its blue hue, although Neptune’s is darker and more vivid. Its atmosphere can be subdivided into two main regions: the lower troposphere (where temperatures decrease with altitude), and the stratosphere (where temperatures increase with altitude).

The lower stratosphere is believed to contain hydrocarbons like ethane and ethyne, which are the result of methane interacting with UV radiation, thus producing Neptune’s atmospheric haze. The stratosphere is also home to trace amounts of carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide, which are responsible for Neptune’s stratosphere being warmer than that of Uranus.

Weather Patterns:

Like Earth, Jupiter experiences auroras near its northern and southern poles. But on Jupiter, the auroral activity is much more intense and rarely ever stops. These are the result of Jupiter’s intense radiation, it’s magnetic field, and the abundance of material from Io’s volcanoes that react with Jupiter’s ionosphere.

Jupiter also experiences violent weather patterns. Wind speeds of 100 m/s (360 km/h) are common in zonal jets, and can reach as high as 620 kph (385 mph). Storms form within hours and can become thousands of km in diameter overnight. One storm, the Great Red Spot, has been raging since at least the late 1600s.

The storm has been shrinking and expanding throughout its history; but in 2012, it was suggested that the Giant Red Spot might eventually disappear. Jupiter also periodically experiences flashes of lightning in its atmosphere, which can be up to a thousand times as powerful as those observed here on the Earth.

Saturn’s atmosphere is similar, exhibiting long-lived ovals now and then that can be several thousands of kilometers wide. A good example is the Great White Spot (aka. Great White Oval), a unique but short-lived phenomenon that occurs once every 30 Earth years. Since 2010, a large band of white clouds called the Northern Electrostatic Disturbance have been observed enveloping Saturn, and is believed to be followed by another in 2020.

The winds on Saturn are the second fastest among the Solar System’s planets, which have reached a measured high of 500 m/s (1800 km/h). Saturn’s northern and southern poles have also shown evidence of stormy weather. At the north pole, this takes the form of a persisting hexagonal wave pattern measuring about 13,800 km (8,600 mi) and rotating with a period of 10h 39m 24s.

The south pole vortex apparently takes the form of a jet stream, but not a hexagonal standing wave. These storms are estimated to be generating winds of 550 km/h, are comparable in size to Earth, and believed to have been going on for billions of years. In 2006, the Cassini space probe observed a hurricane-like storm that had a clearly defined eye. Such storms had not been observed on any planet other than Earth – even on Jupiter.

Uranus’s weather follows a similar pattern where systems are broken up into bands that rotate around the planet, which are driven by internal heat rising to the upper atmosphere. Winds on Uranus can reach up to 900 km/h (560 mph), creating massive storms like the one spotted by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2012. Similar to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, this “Dark Spot” was a giant cloud vortex that measured 1,700 kilometers by 3,000 kilometers (1,100 miles by 1,900 miles).

Because Neptune is not a solid body, its atmosphere undergoes differential rotation, with its wide equatorial zone rotating slower than the planet’s magnetic field (18 hours vs. 16.1 hours). By contrast, the reverse is true for the polar regions where the rotation period is 12 hours. This differential rotation is the most pronounced of any planet in the Solar System, and results in strong latitudinal wind shear and violent storms.

The first to be spotted was a massive anticyclonic storm measuring 13,000 x 6,600 km and resembling the Great Red Spot of Jupiter. Known as the Great Dark Spot, this storm was not spotted five later (Nov. 2nd, 1994) when the Hubble Space Telescope looked for it. Instead, a new storm that was very similar in appearance was found in the planet’s northern hemisphere, suggesting that these storms have a shorter life span than Jupiter’s.

Exoplanets:

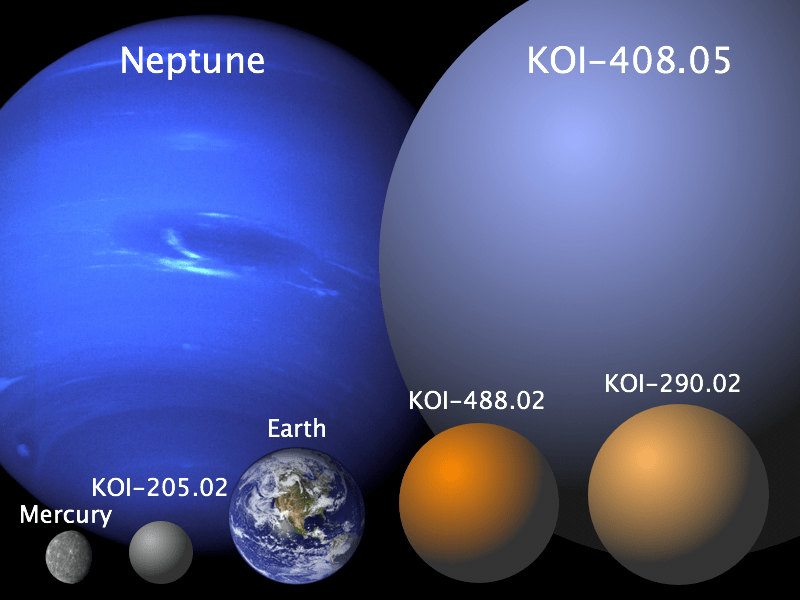

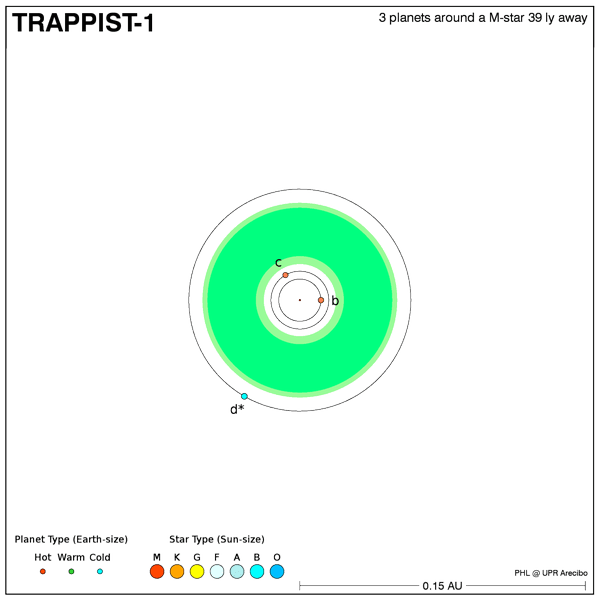

Due to the limitations imposed by our current methods, most of the exoplanets discovered so far by surveys like the Kepler space observatory have been comparable in size to the giant planets of the Solar System. Because these large planets are inferred to share more in common with Jupiter than with the other giant planets, the term “Jovian Planet” has been used by many to describe them.

Many of these planets, being greater in mass than Jupiter, have also been dubbed as “Super-Jupiters” by astronomers. Such planets exist at the borderline between planets and brown dwarf stars, the smallest stars known to exist in our Universe. They can be up to 80 times more massive than Jupiter but are still comparable in size, since their stronger gravity compresses the material into an ever denser, more compact sphere.

Those Super-Jupiters that have distant orbits from their parent stars are known as “Cold Jupiters”, whereas those that have close orbits are called “Hot Jupiters”. A surprising number of Hot Jupiters have been observed by exoplanet surveys, due to the fact that they are particularly easy to spot using the Radial Velocity method – which measures the oscillation of parent stars due to the influence of their planets.

In the past, astronomers believed that Jupiter-like planets could only form in the outer reaches of a star system. However, the recent discovery of many Jupiter-sized planets orbiting close to their stars has cast doubt on this. Thanks to the discovery of Jovians beyond our Solar System, astronomers may be forced to rethink our models of planetary formation.

Since Galileo first observed Jupiter through his telescope, Jovian planets have been an endless source of fascination for us. And despite many centuries of research and progress, there are still many things we don’t know about them. Our latest effort to explore Jupiter, the Juno Mission, is expected to produce some rather interesting finds. Here’s hoping they bring us one step closer to understanding those darn Jovians!

We have written many interesting articles about gas giants here at Universe Today. Here’s the Solar System Guide, The Outer Planets, What’s Inside a Gas Giant?, and Which Planets Have Rings?

For more information, check out NASA’s Solar System Exploration page and Science Daily’s the Jovian planets.

Astronomy Cast has a number of episodes on the Jovian planets, including Episode 56: Jupiter.