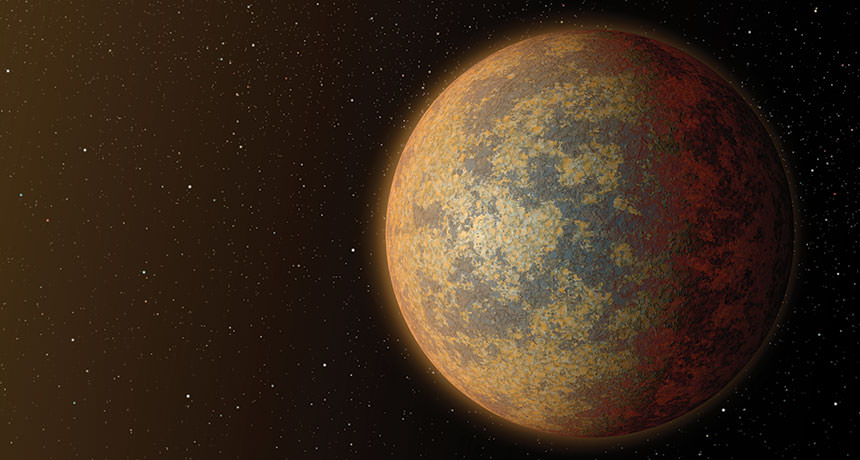

Earth may have a new neighbour, in the form of an Earth-like planet in a solar system only 16 light years away. The planet orbits a star named Gliese 832, and that solar system already hosts two other known exoplanets: Gliese 832B and Gliese 832C. The findings were reported in a new paper by Suman Satyal at the University of Texas, and colleagues J. Gri?th, and Z. E. Musielak.

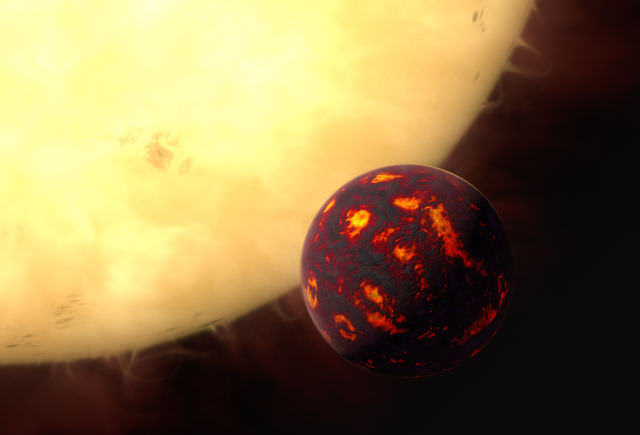

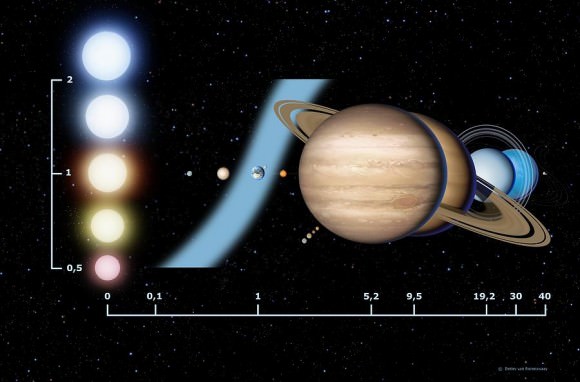

Gliese 832B is a gas giant similar to Jupiter, at 0.64 the mass of Jupiter, and it orbits its star at 3.5 AU. G832B probably plays a role similar to Jupiter in our Solar System, by setting gravitational equilibrium. Gliese 832C is a Super-Earth about 5 times as massive as Earth, and it orbits the star at a very close 0.16 AU. G832C is a rocky planet on the inner edge of the habitable zone, but is likely too close to its star for habitability. Gliese 832, the star at the center of it all, is a red dwarf about half the size of our Sun, in both mass and radius.

The newly discovered planet is still hypothetical at this point, and the researchers put its mass at between 1 and 15 Earth masses, and its orbit at between 0.25 to 2.0 AU from Gliese 582, its host star.

The two previously discovered planets in Gliese 832 were discovered using the radial velocity technique. Radial velocity detects planets by looking for wobbles in the host star, as it responds to the gravitational tug exerted on it by planets in orbit. These wobbles are observable through the Doppler effect, as the light of the affected star is red-shifted and blue-shifted as it moves.

The team behind this study re-analyzed the data from the Gliese 832 system, based on the idea that the vast distance between the two already-detected planets would be home to another planet. According to other solar systems studied by Kepler, it would be highly unusual for such a gap to exist.

As they say in their paper, the main thrust of the study is to explore the gravitational effect that the large outer planet has on the smaller inner planet, and also on the hypothetical Super-Earth that may inhabit the system. The team conducted numerical simulations and created models constrained by what’s known about the Gliese 832 system to conclude that an Earth-like planet may orbit Gliese 832.

This can all sound like some hocus-pocus in a way, as my non-science-minded friends like to point out. Just punch in some numbers until it shows an Earth-like planet, then publish and get attention. But it’s not. This kind of modelling and simulation is very rigorous.

Putting in all the data that’s known about the Gliese 832 system, including radial velocity data, orbital inclinations, and gravitational relationships between the planets and the star, and between the planets themselves, yields bands of probability where previously undetected planets might exist. This result tells planet hunters where to start looking for planets.

In the case of this paper, the result indicates that “there is a slim window of about 0.03 AU where an Earth-like planet could be stable as well as remain in the HZ.” The authors are quick to point out that the existence of this planet is not proven, only possible.

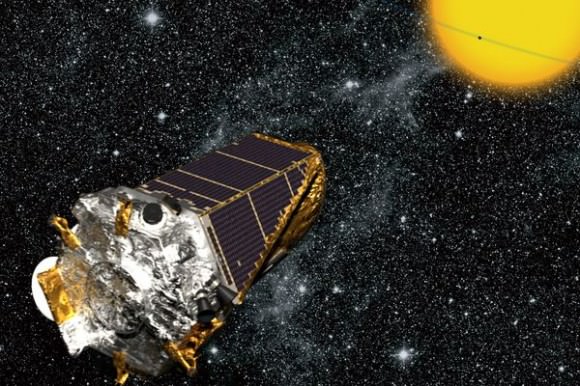

The other planets were found using the radial velocity method, which is pretty reliable. But radial velocity only provides clues to the existence of planets, it doesn’t prove that they’re there. Yet. The authors acknowledge that a larger number of radial velocity observations are needed to confirm the existence of this new planet. Barring that, either the transit method employed by the Kepler spacecraft, or direct observation with powerful telescopes, may also provide positive proof.

So far, the Kepler spacecraft has confirmed the existence of 1,041 planets. But Kepler can’t look everywhere for planets. Studies like these are crucial in giving Kepler starting points in its search for exoplanets. If an exoplanet can be confirmed in the Gliese 832 system, then it also confirms the accuracy of the simulation that the team behind this paper performed.

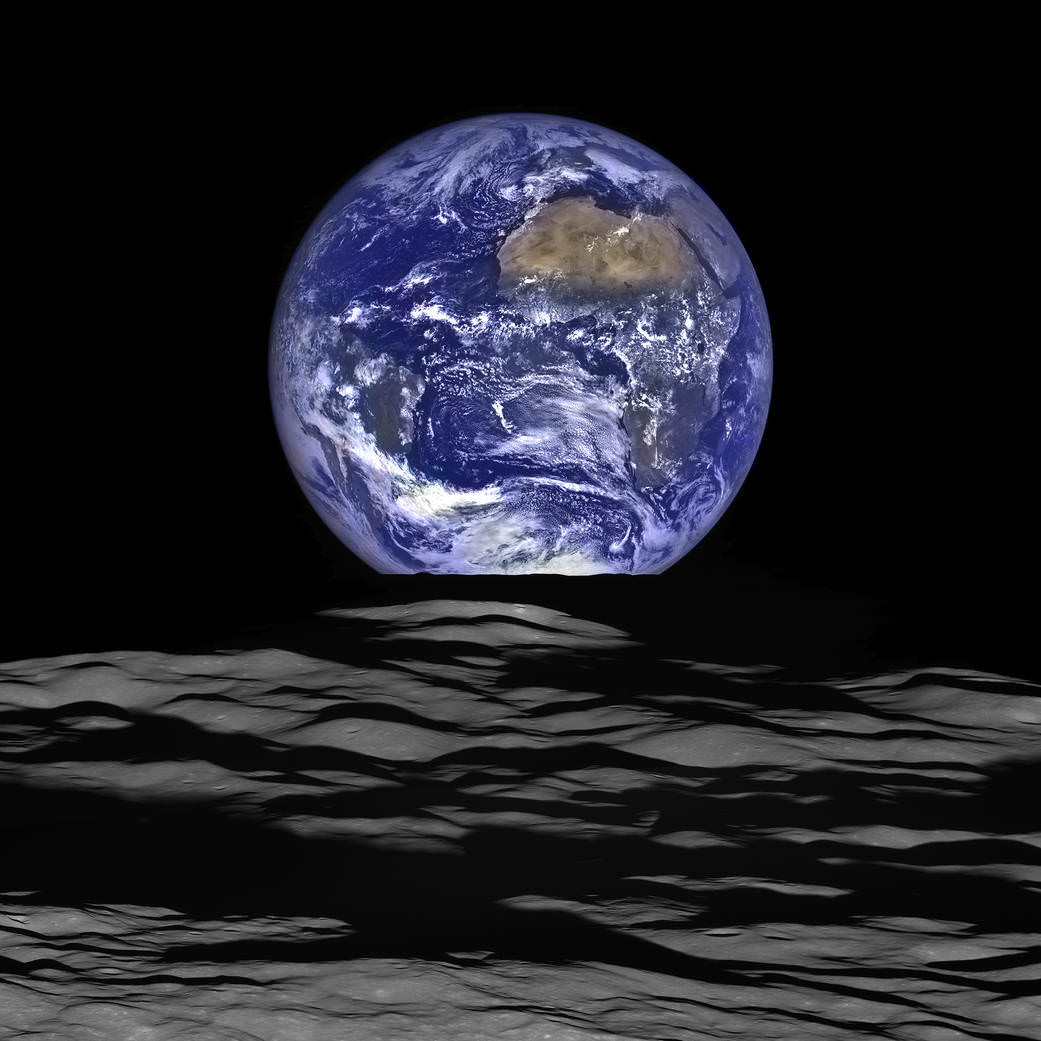

If confirmed, G832 C would join a growing list of exoplanets. It wasn’t long ago that we knew almost nothing about other solar systems. We only had knowledge of our own. And even though it was always unlikely that our Solar System would for some reason be special, we had no certain knowledge of the population of exoplanets in other solar systems.

Studies like this one point to our growing understanding of the dynamics of other solar systems, and the population of exoplanets in the Milky Way, and most likely throughout the cosmos.