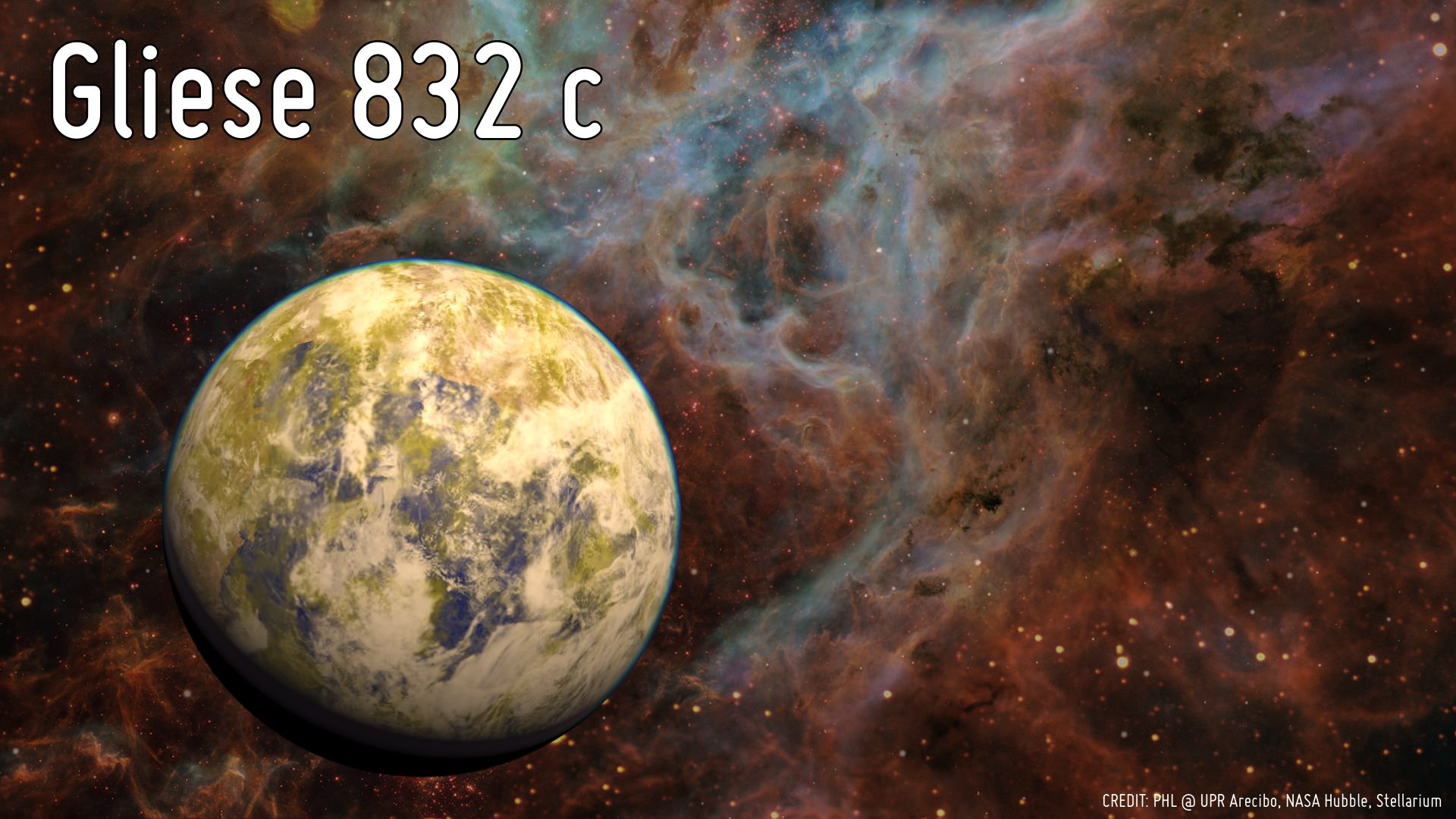

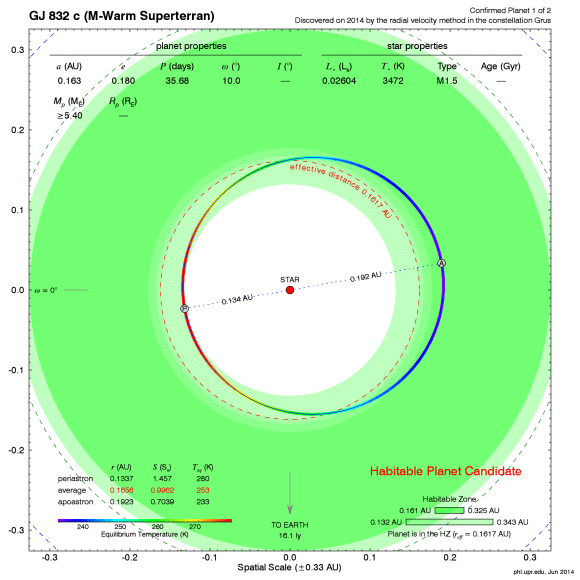

The International Astronomical Union has unveiled a worldwide contest, NameExoWorlds, which gives the public a role in naming planets and their host stars beyond the solar system.

It’s the latest chapter in a years-long controversy over how celestial objects, including exoplanets, are classified and named.

Although the IAU has presided over the long process of naming astronomical objects for nearly a century, until last year they didn’t feel the need to include exoplanets on this long list.

As late as March 2013, the IAU’s official word on naming exoplanets was: “The IAU sees no need and has no plan to assign names to these objects at the present stage of our knowledge.” Since there was seemingly going to be so many exoplanets, the IAU saw it too difficult to name them all.

Other organizations, however, such as the SETI institute and the space company Uwingu leapt at the opportunity to engage the public in providing names for exoplanets. Their endeavors have been widely popular with the general public, but generated discussion about how ‘official’ the names would be.

The IAU issued a later statement in April 2014 (which Universe Today covered with vigor) and claimed that these two campaigns had no bearing on the official naming process. By August 2014, the IAU had introduced new rules for naming exoplanets, drastically changing their stance and surprising many.

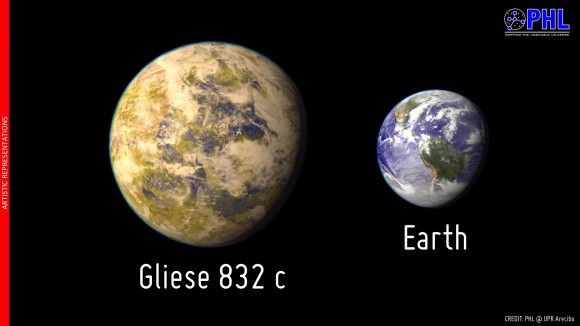

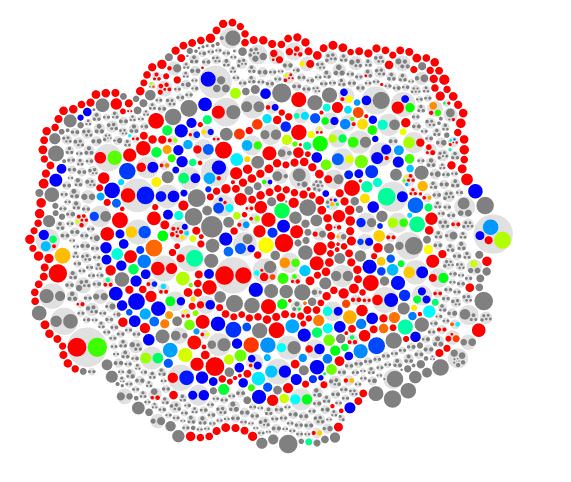

Now in partnership with Zooniverse, a citizen-science organization, the IAU has drawn up a list of 305 well-characterized exoplanets in 206 solar systems. Starting in September, astronomy organizations can register for the opportunity to select planets for naming.

In October, the IAU plans to ask the registered organizations to vote for the 20 to 30 worlds on the list that they want to name. The exact number will depend on the number of registered groups. In December, those groups can propose names for the worlds that get the most votes. Groups can only propose names in accordance with the following set of rules. A name must be:

— 16 characters or less in length

— Preferably one word

— Pronounceable (in some language)

— Non-offensive

— Not too similar to an existing name of an astronomical object

Starting in March 2015, the list of proposed names will be put up to an Internet vote. The winners will be validated by the IAU, and announced during a ceremony at the IAU General Assembly in Honolulu in August 2015.

The popular name for a given exoplanet won’t replace the scientific name. But it will carry the IAU seal of approval.

Astronomer Alan Stern, principal investigator of the New Horizons mission to Pluto and CEO of Uwingu told Universe Today’s Senior Editor, Nancy Atkinson, that he was not surprised by the IAU’s new statement. “To my eye though, it’s just more IAU elitism, they can’t seem to get out of their elitist rut thinking they own the Universe.”

“Uwingu’s model is in our view far superior — people can directly name planets around other stars, with no one having to approve the choices,” Stern continued. “With 100 billion plus planets in the galaxy, why bother with committees of elites telling people what they do and don’t approve of?”

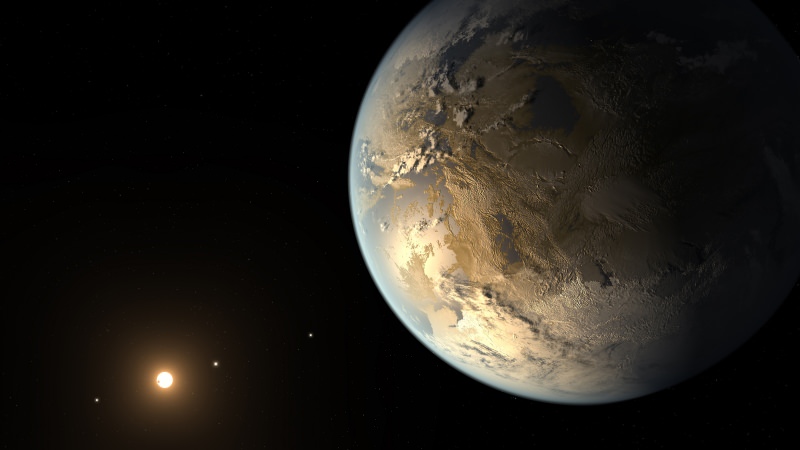

If nothing else, the controversy has sparked multiple venues to name exoplanets and more importantly learn about these alien worlds.