Measuring the atmospheric pressure of a distant exoplanet may seem like a daunting task but astronomers at the University of Washington have now developed a new technique to do just that.

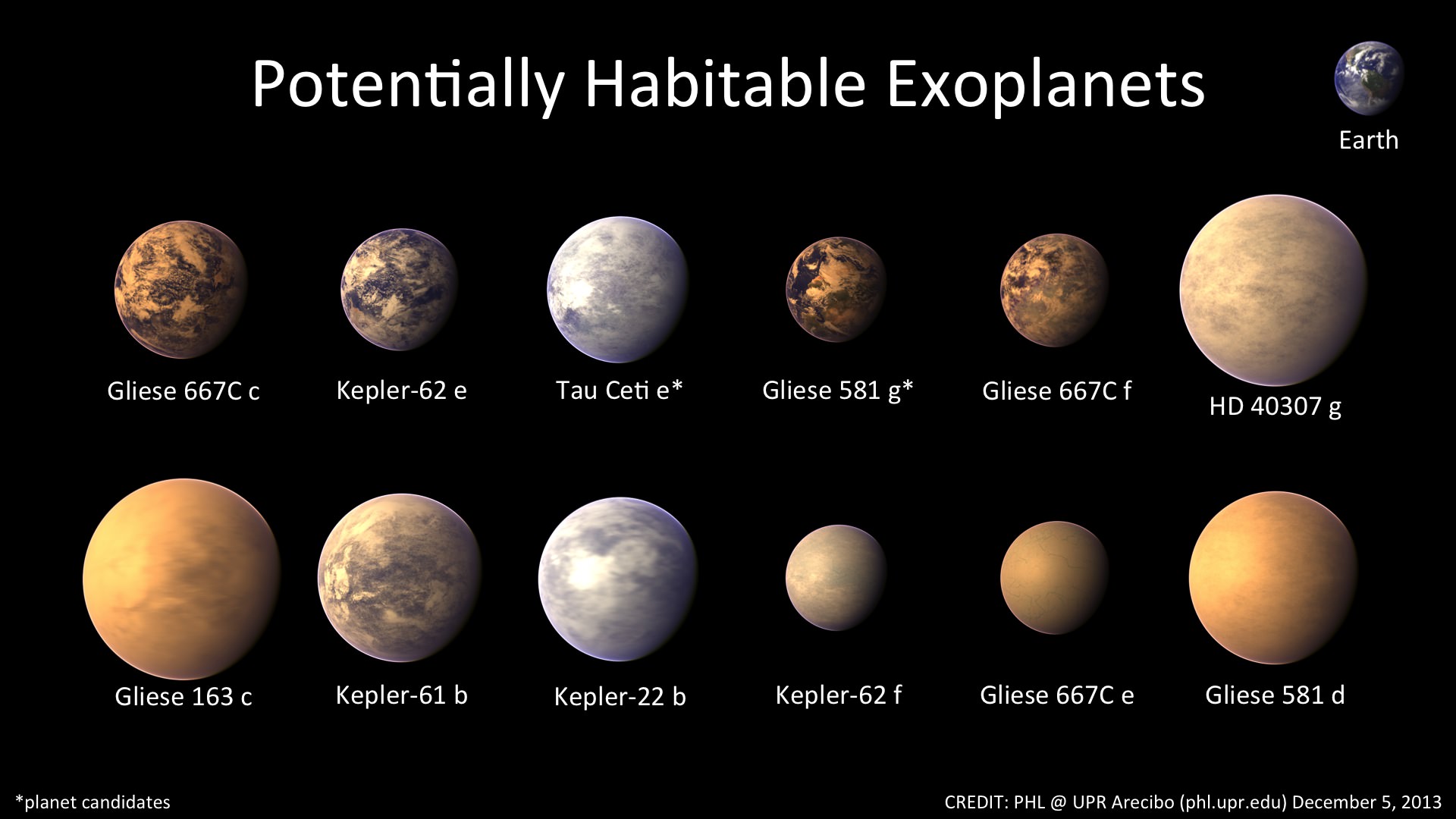

When exoplanet discoveries first started rolling in, astronomers laid emphasis in finding planets within the habitable zone — the band around a star where water neither freezes nor boils. But characterizing the environment and habitability of an exoplanet doesn’t depend on the planet’s surface temperature alone.

Atmospheric pressure is just as important in gauging whether or not the surface of an exoplanet may likely hold liquid water. Anyone familiar with camping at high-altitude should have a good understanding of how pressure affects water’s boiling point.

The method developed by Amit Misra, a PhD candidate, involves isolating “dimers” — bonded pairs of molecules that tend to form at high pressures and densities in a planet’s atmosphere — not to be confused with “monomers,” which are simply free-floating molecules. While there are many types of dimers, the research team focused exclusively on oxygen molecules, which are temporarily bound to each other through hydrogen bonding.

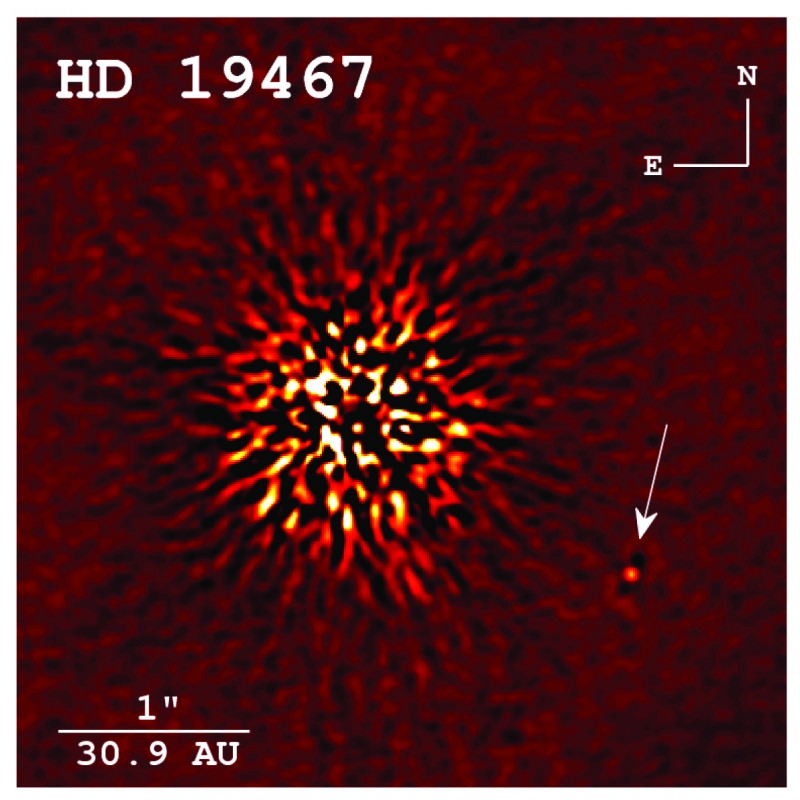

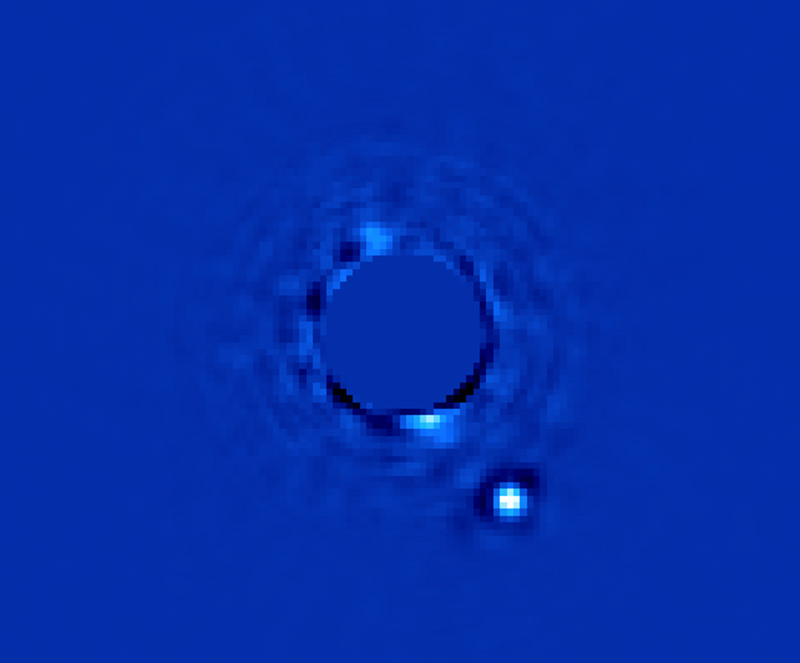

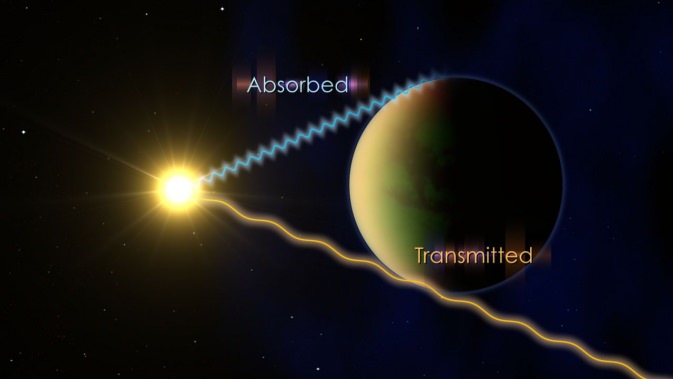

We may indirectly detect dimers in an exoplanet’s atmosphere when the exoplanet transits in front of its host star. As the star’s light passes through a thin layer of the planet’s atmosphere the dimers absorb certain wavelengths of it. Once the starlight reaches Earth it’s imprinted with the chemical fingerprints of the dimers.

Dimers absorb light in a distinctive pattern, which typically has four peaks due to the rotational motion of the molecules. But the amount of absorption may change depending on the atmospheric pressure and density. This difference is much more pronounced in dimers than in monomers, allowing astronomers to gain additional information about the atmospheric pressure based on the ratio of these two signatures.

While water dimers were detected in the Earth’s atmosphere as early as last year, powerful telescopes soon to come online may enable astronomers to use this method in observing distant exoplanets. The team analyzed the likelihood of using the James Webb Space Telescope to make such a detection and found it challenging but possible.

Detecting dimers in an exoplanet’s atmosphere would not only help us evaluate the atmospheric pressure, and therefore the state of water on the surface, but other biosignature markers as well. Oxygen is directly tied to photosynthesis, and will most likely not be abundant in an exoplanet’s atmosphere unless it is regularly produced by algae or other plants.

“So if we find a good target planet, and you could detect these dimer molecules — which might be possible within the next 10 to 15 years — that would not only tell you something about pressure, but actually tell you that there’s life on that planet,” said Misra in a press release.

The paper has been published in the February issue of Astrobiology and is available for download here.