Hunters of alien life may have a new and unsuspected niche to scout out.

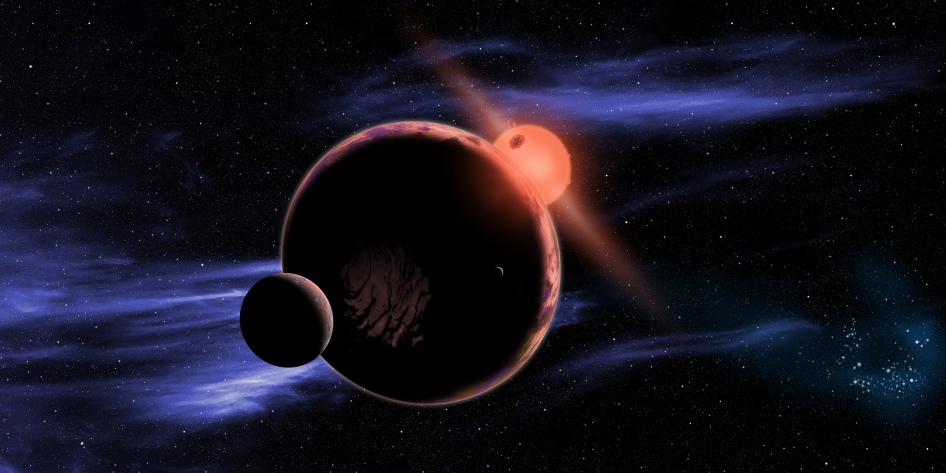

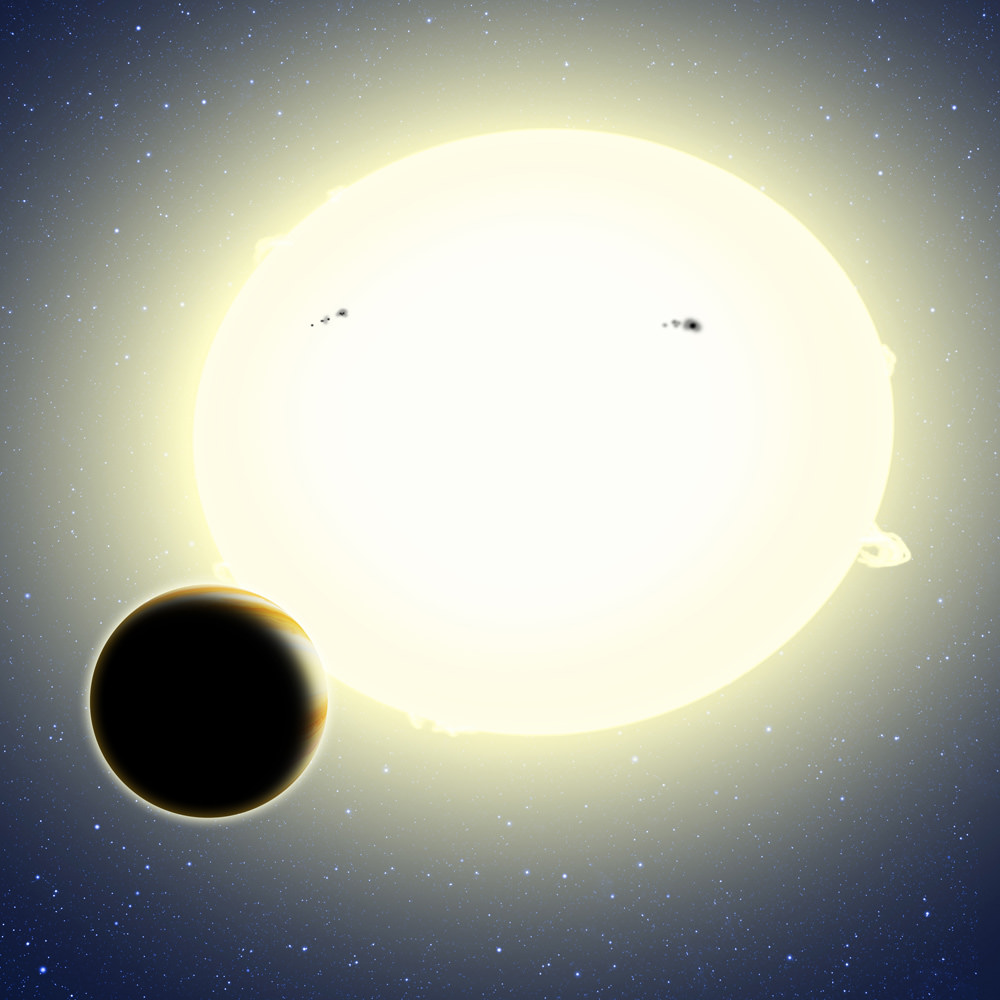

A recent paper submitted by Associate Professor of Astronomy at Columbia University Kristen Menou to the Astrophysical Journal suggests that tidally-locked planets in close orbits to M-class red dwarf stars may host a very unique hydrological cycle. And in some extreme cases, that cycle may cause a curious dichotomy, with ice collecting on the farside hemisphere of the world, leaving a parched sunward side. Life sprouting up in such conditions would be a challenge, experts say, but it is — enticingly — conceivable.

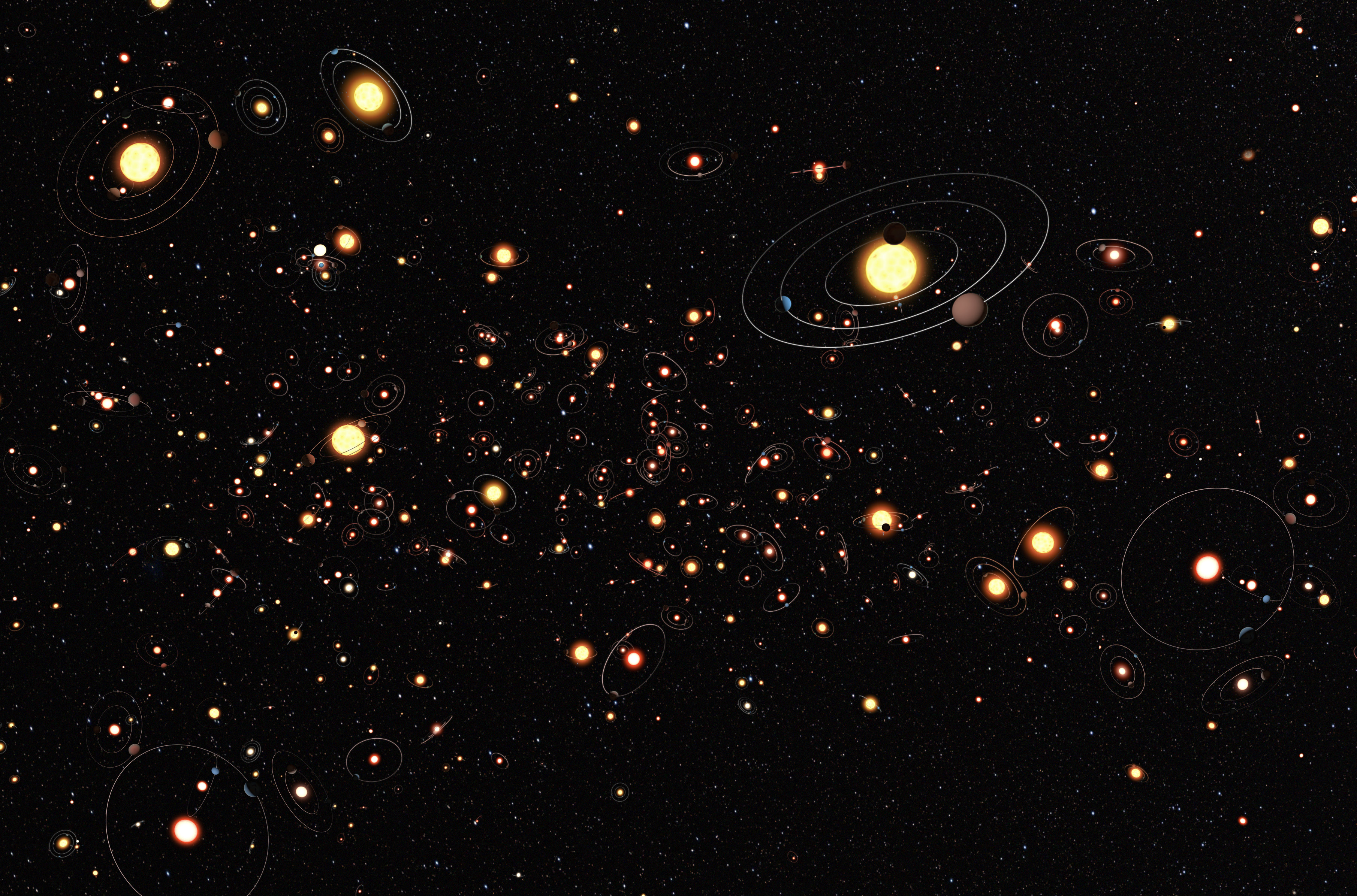

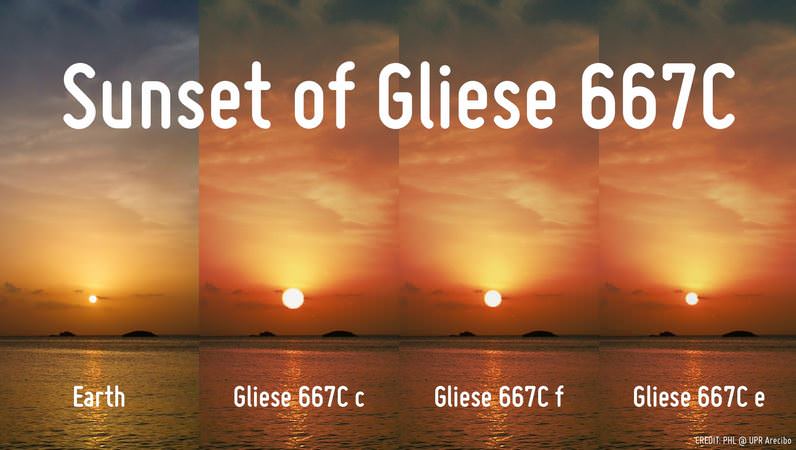

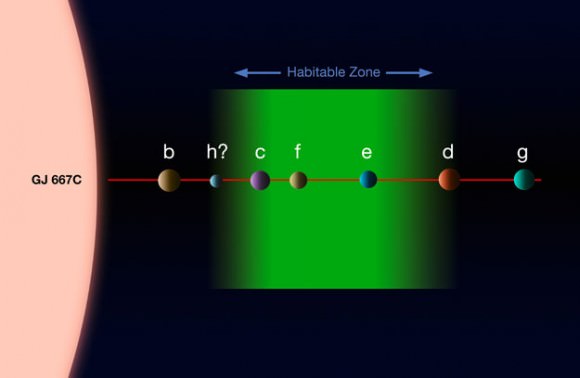

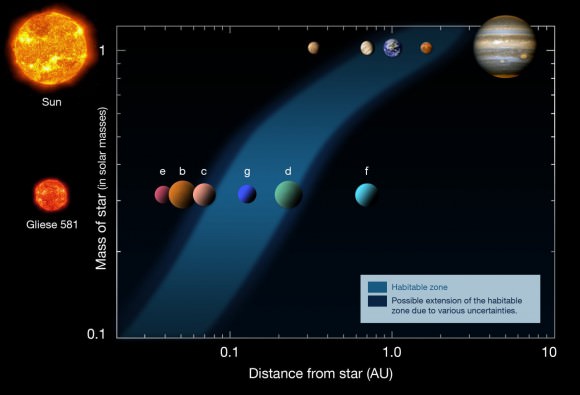

The possibility of life around red dwarf stars has tantalized researchers before. M-type dwarfs are only 0.075 to 0.6 times as massive as our Sun, and are much more common in the universe. The life span of these miserly stars can be measured in the trillions of years for the low end of the mass scale. For comparison, the Universe has only been around for 13.8 billion years. This is another plus in the game of giving biological life a chance to get underway. And while the habitable zone, or the “Goldilocks” region where water would remain liquid is closer in to a host star for a planet orbiting a red dwarf, it is also more extensive than what we inhabit in our own solar system.

But such a scenario isn’t without its drawbacks. Red dwarfs are turbulent stars, unleashing radiation storms that would render any nearby planets sterile for life as we know it.

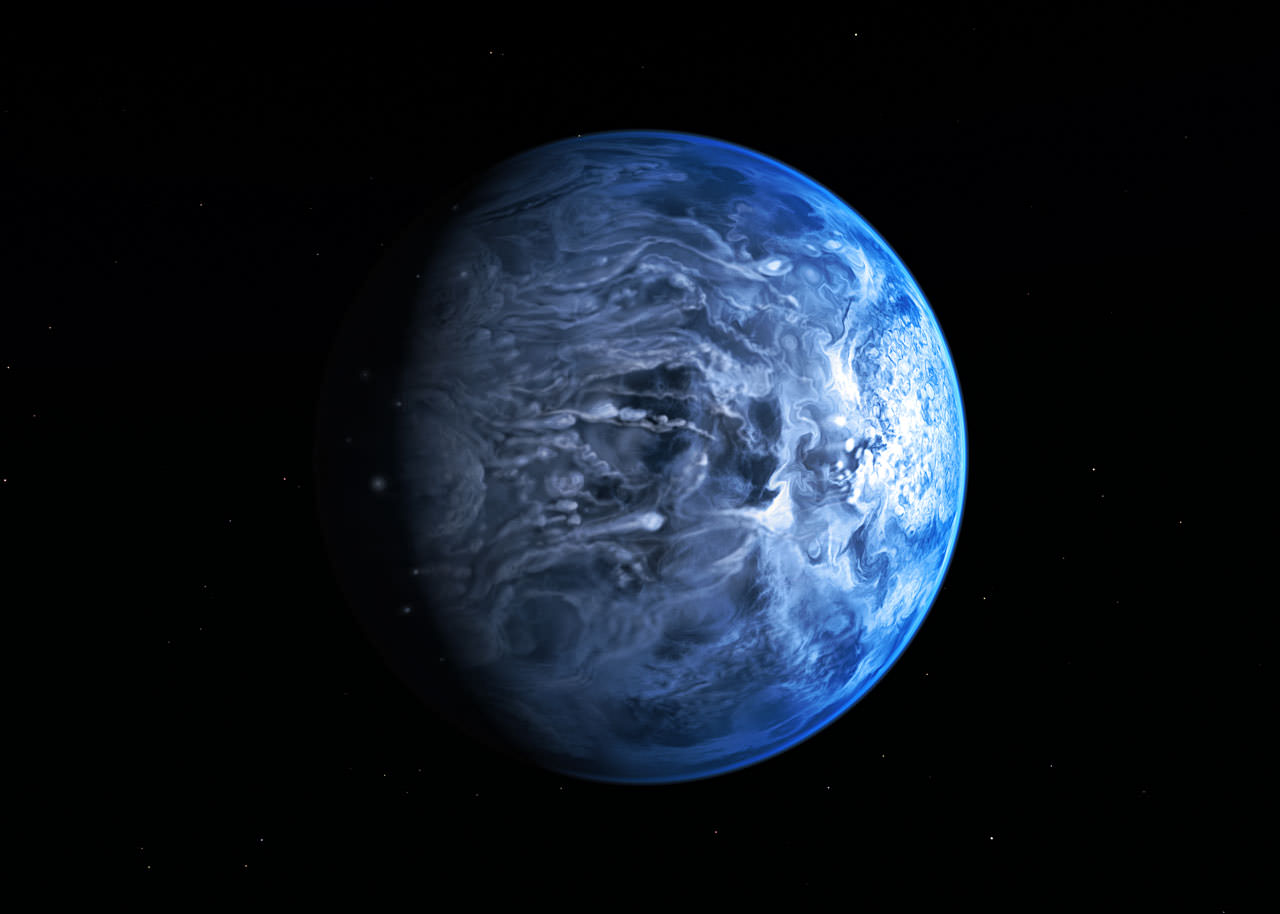

But the model Professor Menou proposes paints a unique and compelling picture. While water on the permanent daytime side of a terrestrial-sized world tidally locked in orbit around an M-dwarf star would quickly evaporate, it would be transported by atmospheric convection and freeze out and accumulate on the permanent nighttime side. This ice would only slowly migrate back to the scorching daytime side and the process would continue.

Could these types of “water-locked worlds” be more common than our own?

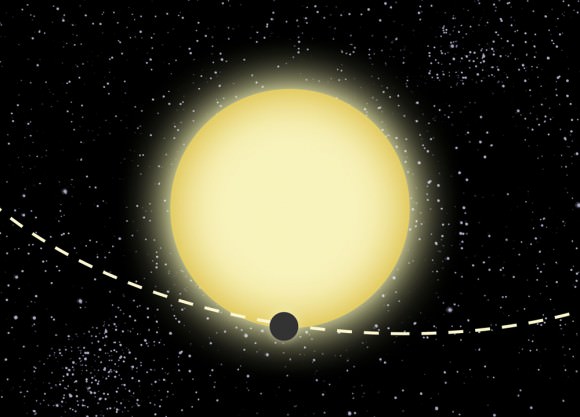

The type of tidal locking referred to is the same as has occurred between the Earth and its Moon. The Moon keeps one face eternally turned towards the Earth, completing one revolution every 29.5 day synodic period. We also see this same phenomenon in the satellites for Jupiter and Saturn, and such behavior is most likely common in the realm of exoplanets closely orbiting their host stars.

The study used a dynamical model known as PlanetSimulator created at the University of Hamburg in Germany. The worlds modeled by the author suggest that planets with less than a quarter of the water present in the Earth’s oceans and subject to a similar insolation as Earth from its host star would eventually trap most of their water as ice on the planet’s night side.

Kepler data results suggest that planets in close orbits around M-dwarf stars may be relatively common. The author also notes that such an ice-trap on a water-deficient world orbiting an M-dwarf star would have a profound effect of the climate, dependent on the amount of volatiles available. This includes the possibility of impacts on the process of erosion, weathering, and CO2 cycling which are also crucial to life as we know it on Earth.

Thus far, there is yet to be a true “short list” of discovered exoplanets that may fit the bill. “Any planet in the habitable zone of an M-dwarf star is a potential water-trapped world, though probably not if we know the planet possesses a thick atmosphere.” Professor Menou told Universe Today. “But as more such planets are discovered, there should be many more potential candidates.”

Being that red dwarf stars are relatively common, could this ice-trap scenario be widespread as well?

“In short, yes,” Professor Menou said to Universe Today. “It also depends on the frequency of planets around such stars (indications suggest it is high) and on the total amount of water at the surface of the planet, which some formation models suggest should indeed be small, which would make this scenario more likely/relevant. It could, in principle, be the norm rather than the exception, although it remains to be seen.”

Of course, life under such conditions would face the unique challenges. The daytime side of the world would be subject to the tempestuous whims of its red dwarf host sun in the form of frequent radiation storms. The cold nighttime side would offer some respite from this, but finding a reliable source of energy on the permanently shrouded night side of such as world would be difficult, perhaps relying on chemosynthesis instead of solar-powered photosynthesis.

On Earth, life situated near “black smokers” or volcanic vents deep on the ocean floor where the Sun never shines do just that. One could also perhaps imagine life that finds a niche in the twilight regions of such a world, feeding on the detritus that circulates by.

Some of the closest red dwarf stars to our own solar system include Promixa Centauri, Barnard’s Star and Luyten’s Flare Star. Barnard’s star has been the target of searches for exoplanets for over a century due to its high proper motion, which have so far turned up naught.

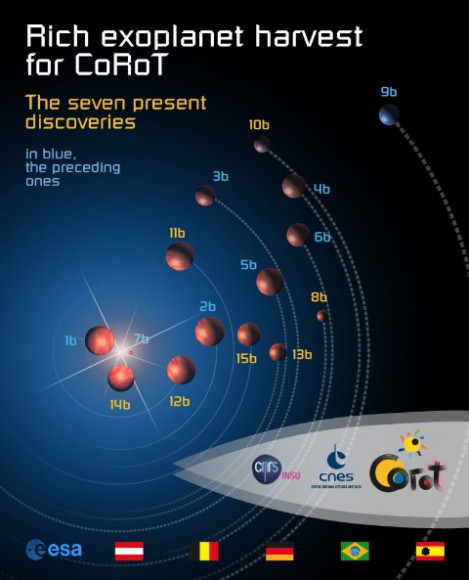

The closest M-dwarf star with exoplanets discovered thus far is Gliese 674, at 14.8 light years distant. The current tally of extrasolar worlds as per the Extrasolar Planet Encyclopedia stands at 919.

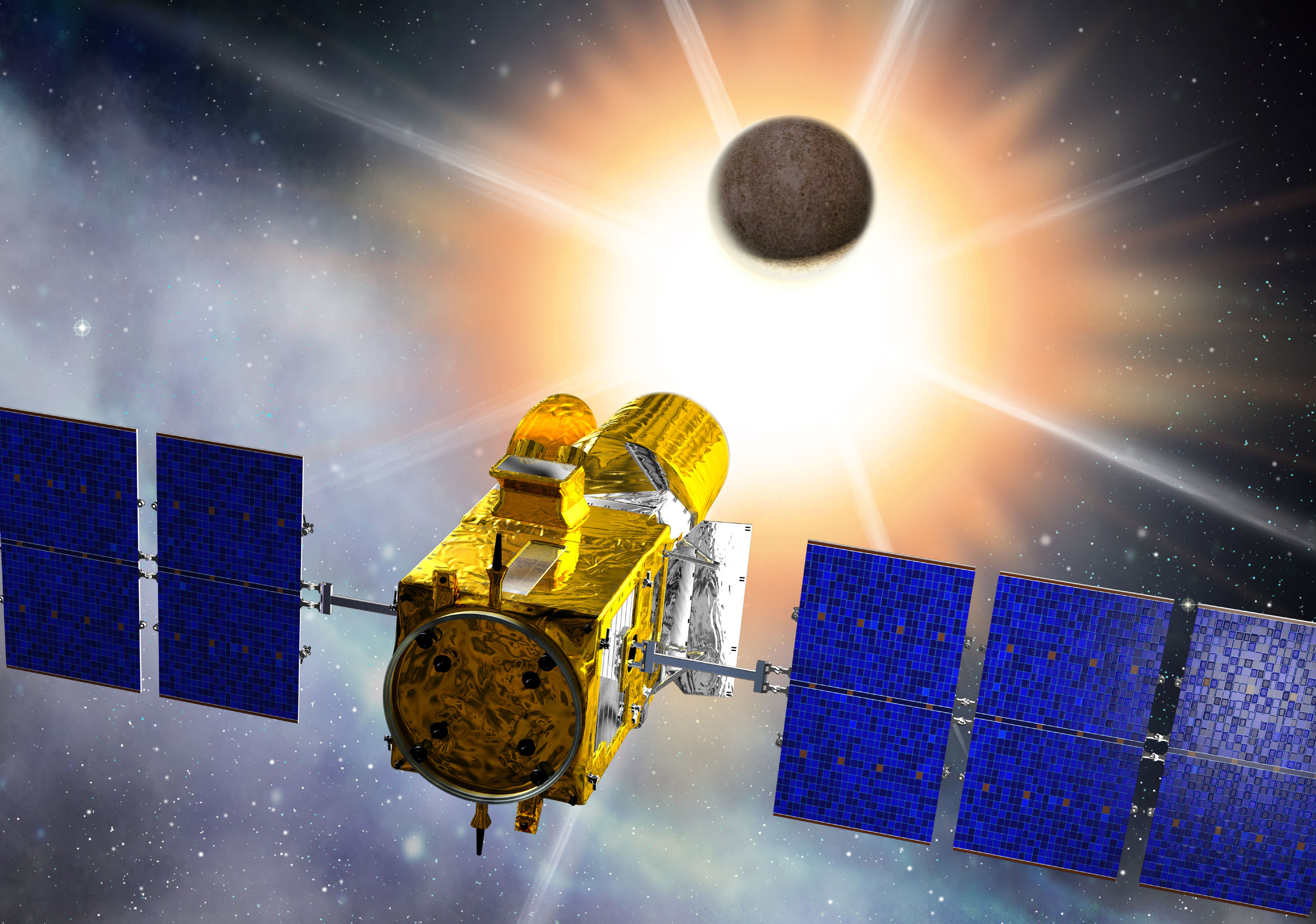

This hunt will also provide a challenge for TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite and the successor to Kepler due to launch in 2017.

Searching for and identifying ice-trapped worlds may prove to be a challenge. Such planets would exhibit a contrast in albedo, or brightness from one hemisphere to the other, but we would always see the ice-covered nighttime side in darkness. Still, exoplanet-hunting scientists have been able to tease out an amazing amount of information from the data available before- perhaps we’ll soon know if such planetary oases exist far inside the “snowline” orbiting around red dwarf stars.

Read the paper on Water-Trapped Worlds at the following link.