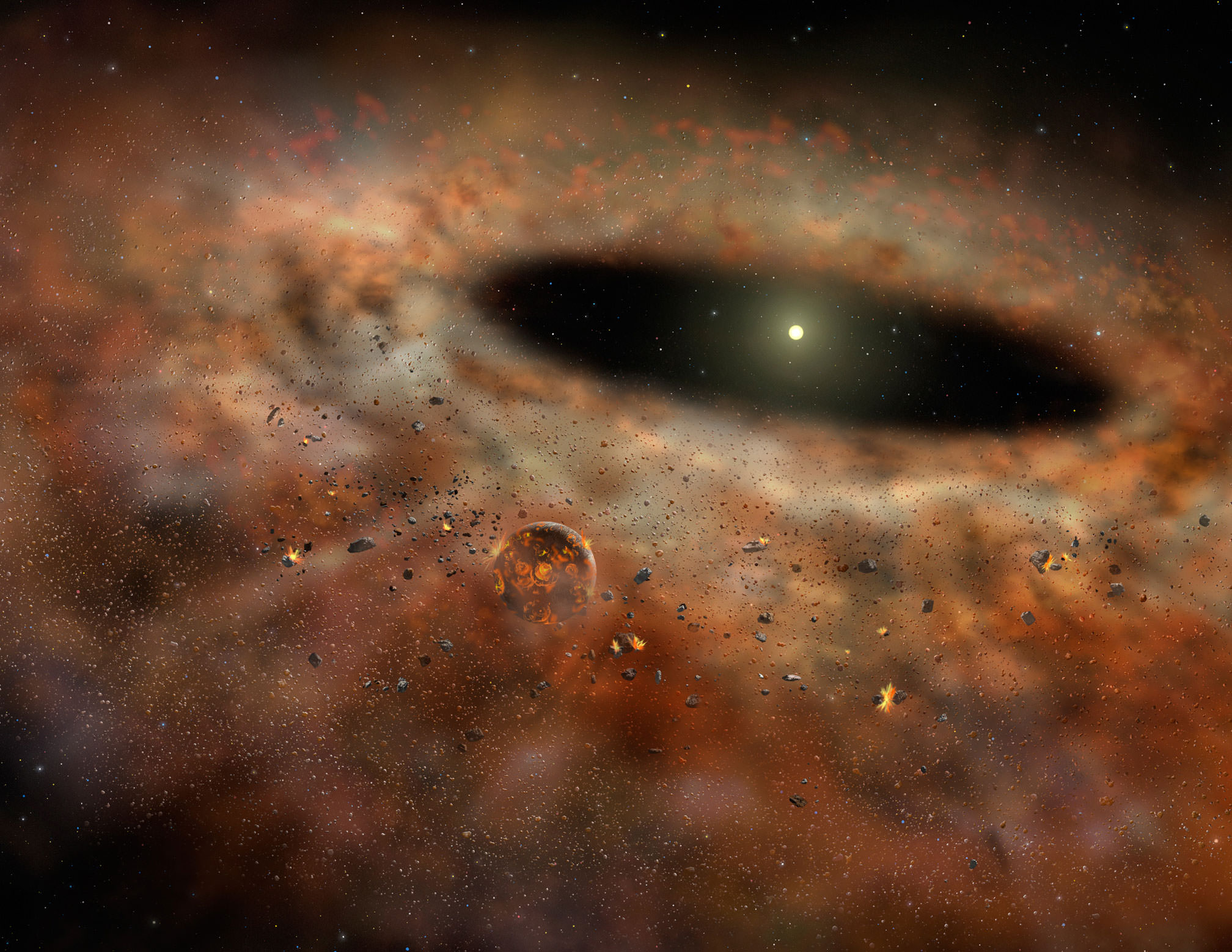

Artist’s depiction of the Kepler 10 system, which contains planets 2.2 and 1.4 times the size of Earth. (NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech)

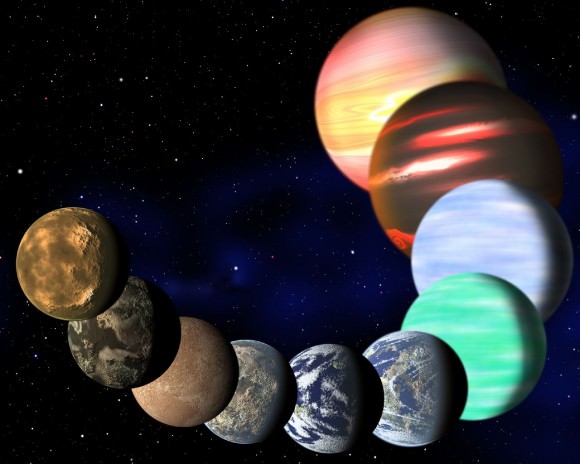

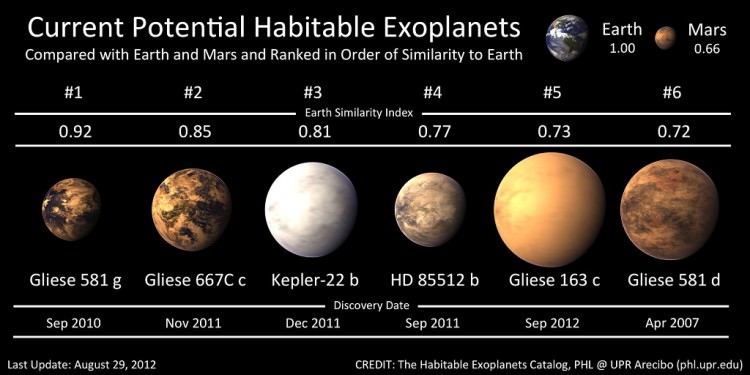

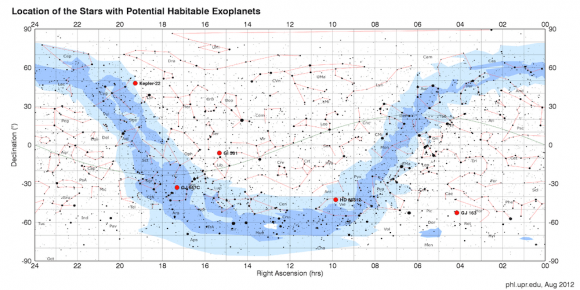

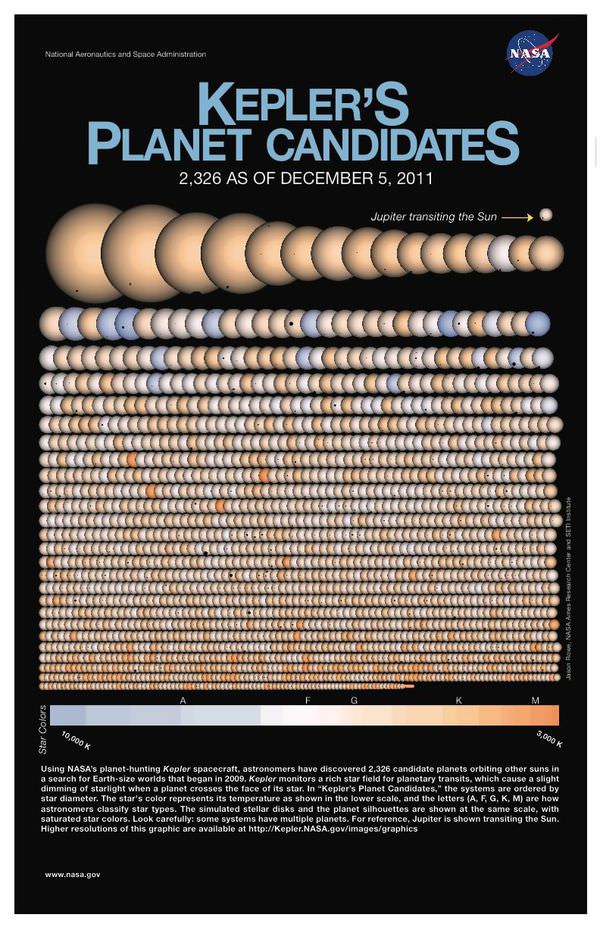

Kepler mission scientists announced today the discovery of literally hundreds of new exoplanet candidates — 461, to be exact — orbiting distant stars within a relatively small cross-section of our galaxy, bringing the total number of potential planets awaiting confirmation to 2,740. What’s more, at least 4 of these new candidates appear to be fairly Earth-sized worlds located within their stars’ habitable zone, the orbital “sweet spot” where surface water could exist as a liquid.

Impressive results, considering that NASA’s planet-hunting spacecraft was launched a little under 4 years ago (and watching 150,000 stars to spot the shadows of planets is no easy task!)

“… the ways by which men arrive at knowledge of the celestial things are hardly less wonderful than the nature of these things themselves.”

— Johannes Kepler

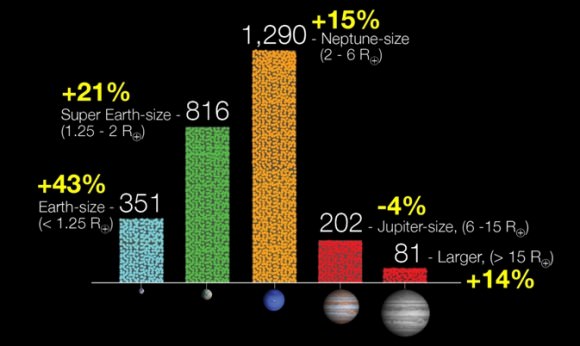

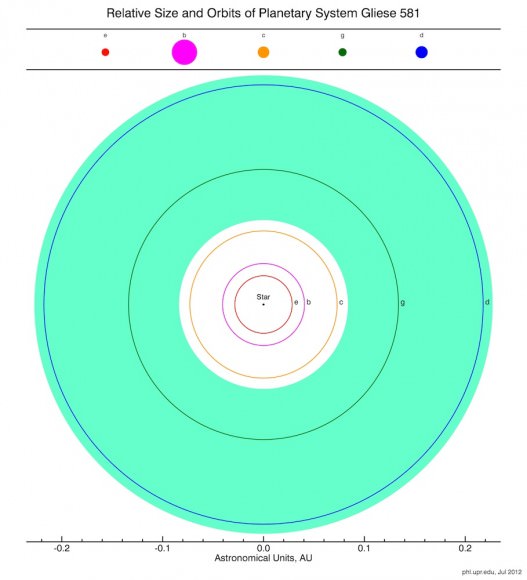

Since the last official announcement of Kepler candidates in Feb. 2012 the number of smaller Earth- and super-Earth-sized worlds observed has risen considerably, as well as the identification of multi-planet systems that are organized more-or-less along a flat plane… just like ours.

“There is no better way to kickoff the start of the Kepler extended mission,” said Kepler scientist Christopher Burke, “than to discover more possible outposts on the frontier of potentially life bearing worlds.”

Read more: First Earth-Sized Exoplanets Found by Kepler

From the NASA press release:

Since the last Kepler catalog was released in February 2012, the number of candidates discovered in the Kepler data has increased by 20 percent and now totals 2,740 potential planets orbiting 2,036 stars. The most dramatic increases are seen in the number of Earth-size and super Earth-size candidates discovered, which grew by 43 and 21 percent respectively.

The new data increases the number of stars discovered to have more than one planet candidate from 365 to 467. Today, 43 percent of Kepler’s planet candidates are observed to have neighbor planets.

The most dramatic increases are seen in the number of Earth-size and super Earth-size candidates discovered, which grew by 43 and 21 percent respectively. (NASA)

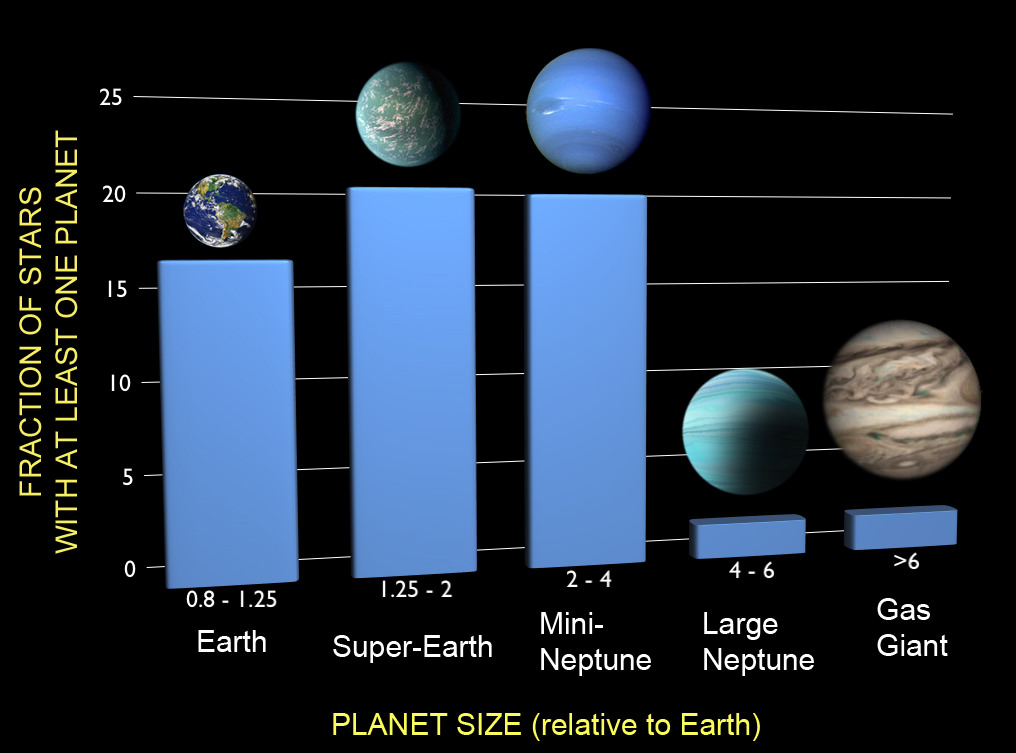

Although some of the new candidates announced today are large Neptune-sized planets, more than half are Earth- to super-Earth sized worlds less than twice the radius of our own planet.

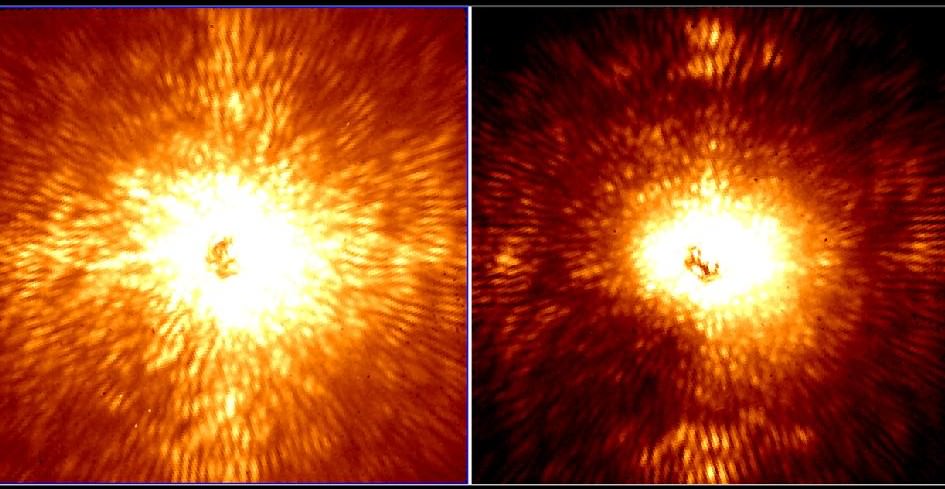

In order for Kepler candidates to be “officially” called exoplanets, they must be observed 3 times on a regular orbit — that is, their signature dimming of the light from their home star must occur as predicted once their presence and then orbital period is calculated. Only then is an exoplanet confirmed.

In order for Kepler candidates to be “officially” called exoplanets, they must be observed 3 times on a regular orbit — that is, their signature dimming of the light from their home star must occur as predicted once their presence and then orbital period is calculated. Only then is an exoplanet confirmed.

To date Kepler has confirmed 105 exoplanets.

The longer the mission continues, the better the chance that Kepler will be able to confirm smaller Earth-sized worlds in longer-period orbits.

Read more: Kepler Mission Extended to 2016

“The analysis of increasingly longer time periods of Kepler data uncovers smaller planets in longer period orbits — orbital periods similar to Earth’s,” said Steve Howell, Kepler mission scientist. “It is no longer a question of will we find a true Earth analogue, but a question of when.”

Scientists analyzed more than 13,000 transit-like signals called ‘threshold crossing events’ to eliminate known spacecraft instrumentation and astrophysical false positives, phenomena that masquerade as planetary candidates, to identify the potential new planets. Watch the video below to see how Kepler observes the light-curve of transit events.

Read more on the NASA press release, and learn more about the Kepler mission here.