[/caption]

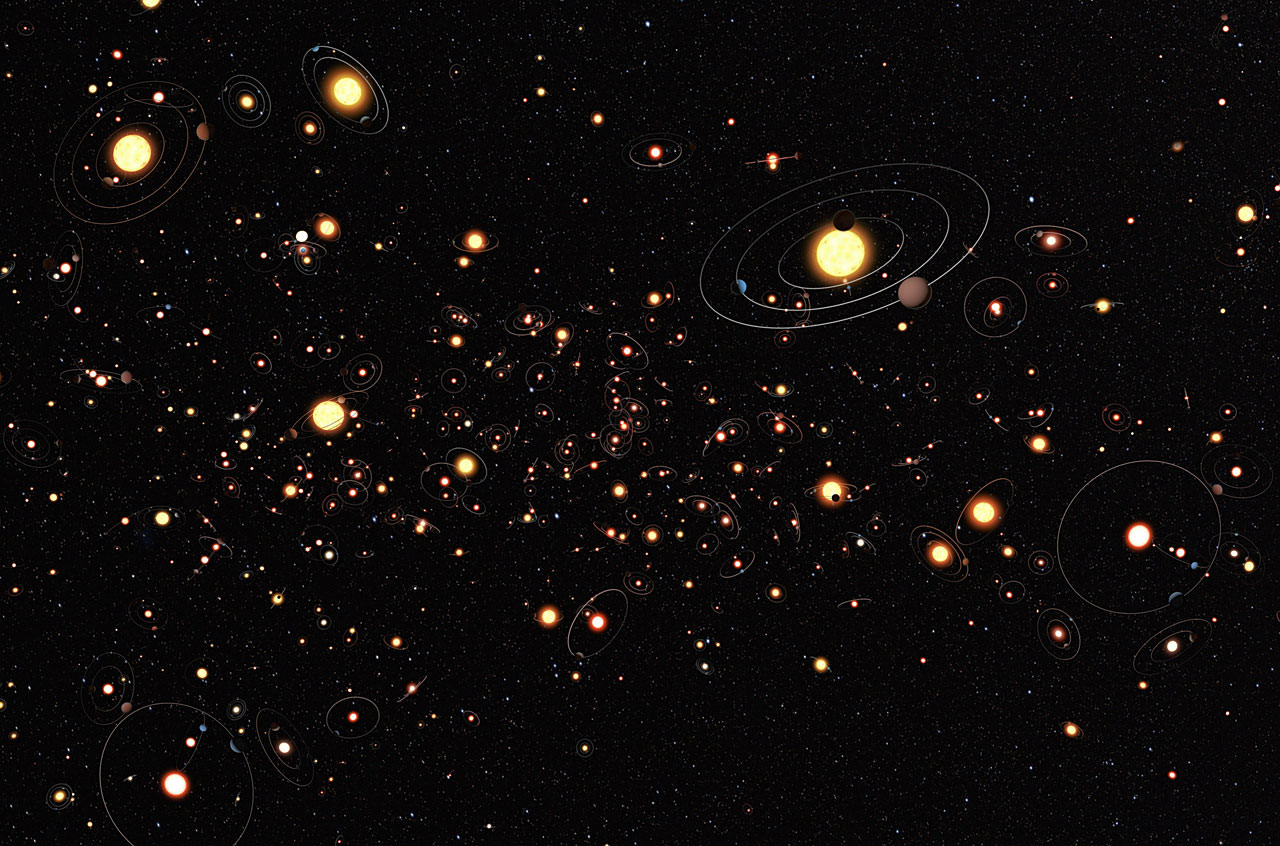

Could the number of wandering planets in our galaxy – planets not orbiting a sun — be more than the amount of stars in the Milky Way? Free-floating planets have been predicted to exist for quite some time and just last year, in May 2011, several orphan worlds were finally detected. But now, the latest research concludes there could be 100,000 times more free-floating planets in the Milky Way than stars. Even though the author of the study, Louis Strigari from the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC), called the amount “an astronomical number,” he said the math is sound.

“Even though this is a large number, it is actually consistent with the amount of mass and heavy elements in our galaxy,” Strigari told Universe Today. “So even though it sounds like a big number, it puts into perspective that there could be a lot more planets and other ‘junk’ out in our galaxy than we know of at this stage.”

And by the way, these latest findings certainly do not lend any credence to the theory of a wandering planet named Nibiru.

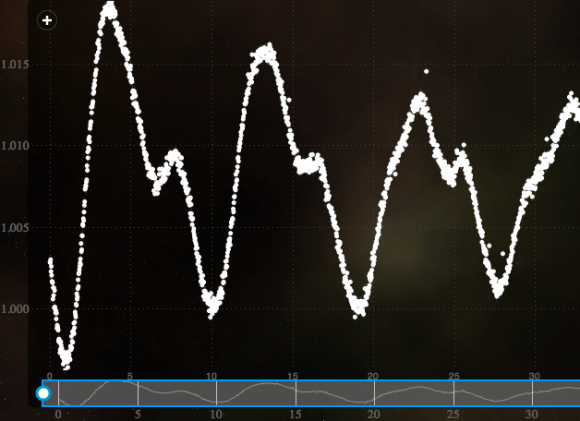

Several studies have suggested that our galaxy could perhaps be swarming with billions of these wandering “nomad” planets, and the research that actually found a dozen or so of these objects in 2011 used microlensing to identify Jupiter-sized orphan worlds between 10,000 and 20,000 light-years away. That research concluded that based on the number of planets identified and the area studied, they estimated that there could literally be hundreds of billions of these lone planets roaming our galaxy….literally twice as many planets as there are stars.

But the new study from Kavli estimates that lost, homeless worlds may be up to 50,000 times more common than that.

Using mathematical extrapolations and relying on theoretical variables, Strigari and his team took into account the known gravitational pull of the Milky Way galaxy, the amount of matter available to make such objects and how that matter might be distributed into objects ranging from the size of Pluto to larger than Jupiter.

“What we did was we put together the observations of what the galaxy is made of, what kind of elements it has, as well as how much mass there could possibly be that has been deduced from the gravitational pull from the stars we observed,” Stigari said via phone. “There are a couple of general bounds we used: you can’t have more nomads in the galaxy than the matter we observe, as well as you probably can’t have more than the amount of so called heavy elements than we observe in the galaxy (anything greater that helium on the periodic table).”

But any study of this type is limited by the lack of understanding of planetary formation.

“We don’t at this stage have a good theory that tells us how planets form,” Strigari said, “so it is difficult to predict from a straight theoretical model how many of these objects might be wandering around the galaxy.”

Strigari said their approach was largely empirical. “We asked how many could there possibly be, consistent with the broad constraints, that gives us a limit to how many these objects could possibly exist.”

So, in absence of any theory that really predicts how many of these things should exist, the estimate of 100,000 times the amount of stars in the Milky Way is an upper limit.

“A lot of times in science and astronomy, in order to learn what the galaxy and universe is made of, we first have to ask questions, what is it not made of, and so you start from an upper bound of how many of these planets there could be,”Strigari said. “Maybe when our data gets better we will start reducing this limit and then we can start learning from empirical observations and start having more constrained observations that go into your theoretical models.”

In other words, Strigari said, it doesn’t mean this is the final answer, but this is the state of our knowledge right now. “It kind of quantifies our ignorance, you could say,” he said.

A good count, especially of the smaller objects, will have to wait for the next generation of big survey telescopes, especially the space-based Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope and the ground-based Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, both set to begin operation in the early 2020s.

So, where did all these potential free range planets come from? One option is that they formed like stars, directly from the collapse of interstellar gas clouds. According to Strigari some were probably ejected from solar systems. Some research has indicated that ejected planets could be rather common, as planets tend to migrate over time towards the star, and as they plow through the material left over from the solar system’s formation, any other planet between them and their star will be affected. Phil Plait explained it as, “some will shift orbit, dropping toward the star themselves, others will get flung into wide orbits, and others still will be tossed out of the system entirely.”

Don’t worry – our own solar system is stable now, but it could have happened in the past, and some research has suggested we originally started out with more planets in our solar system, but some may have been ejected.

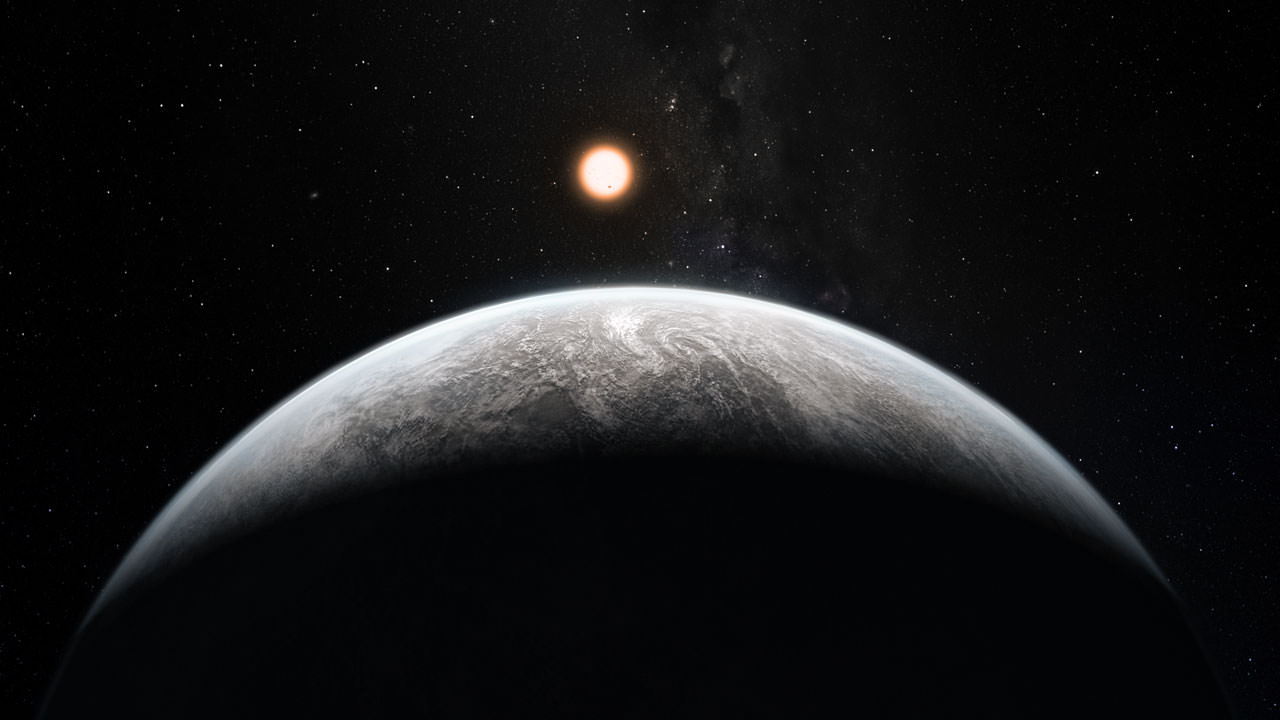

Of course, when discussing planets, the first thing to pop into many people’s minds is if a wandering planet could be habitable.

“If any of these nomad planets are big enough to have a thick atmosphere, they could have trapped enough heat for bacterial life to exist,” Strigari said. Although nomad planets don’t bask in the warmth of a star, they may generate heat through internal radioactive decay and tectonic activity.

As far as a Nibiru-type wandering world in our solar system right now the answer is no. There is no evidence or scientific basis whatsoever for such a planet. If it was out there and heading towards Earth for a December 21, 2012 meetup, we would have seen it or its effects by now.

Sources: Stanford University, conversation with Louis Strigari