Last year, physicists worked out the plausibility of a fully functional (if not fictional) Death Star being able to destroy planets, and found that the Galactic Empire’s technological terror could indeed destroy Earth-like rocky planets, but a Jupiter-sized gas planet would be a tough challenge.

Now, real but theoretical modeling confirms that gas giants like Jupiter would be really hard to destroy by any means, including by stars that undergo periodic outbursts. Actual stars, that is, not Death Stars.

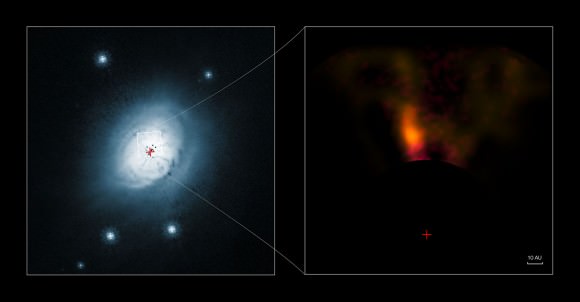

Alan Boss is a noted astrophysicist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, who likes to create three dimensional models of planetary systems. In his recent work, he created 3-D models to help understand the possible origins of Jupiter and Saturn, two gas giants in our Solar System.

He created different models of new stars, which are surrounded by rotating gas disks where planets are thought to form. His models were based on different theories of planetary formation, such as that planets could form from slowly growing ice and rock cores, followed by rapid accretion of gas from the surrounding disk, or that planets form from clumps of dense gas, which increase in mass and density, forming a gas giant planet in a single step.

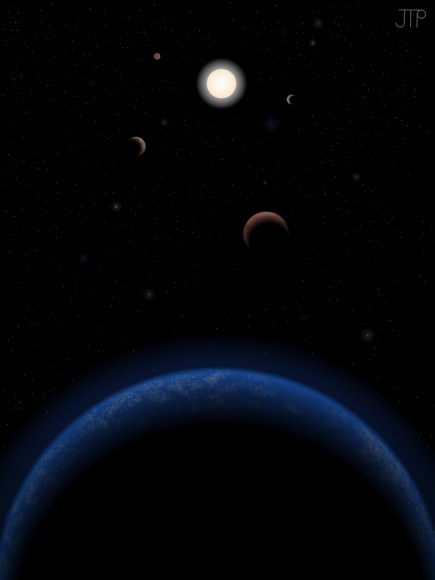

What he found was, that regardless of how gas giant planets form, they should be able to survive periodic outbursts of mass transfer from the gas disk onto the young star. One model similar to our own Solar System was stable for more than 1,000 years, while another model containing planets similar to our Jupiter and Saturn was stable for more than 3,800 years. The models showed that these planets were able to avoid being forced to migrate inward to be swallowed by the growing proto-sun, or being tossed completely out of the planetary system by close encounters with each other.

“Gas giant planets, once formed, can be hard to destroy,” said Boss, “even during the energetic outbursts that young stars experience.”

Some Sun-like stars undergo these periodic outbursts which can last about 100 years. The Death Star, on the other hand — which according to Star Wars lore, is a moon-sized battle station designed to spread fear throughout the galaxy – uses short bursts of its hypermatter reactor superlaser. However, the Death Star’s main power reactor is said to have the energy output equal to several main-sequence stars. But to destroy a planet like Jupiter, all power from essential systems and life support would be required, which is not necessarily possible.

So, in all cases – real, theoretical and fictional — gas giants appear to be safe!

You can read the about the Death Star paper here (from physicists who apparently had some time on their hands) here, and read about Boss’s theoretical modeling of here.

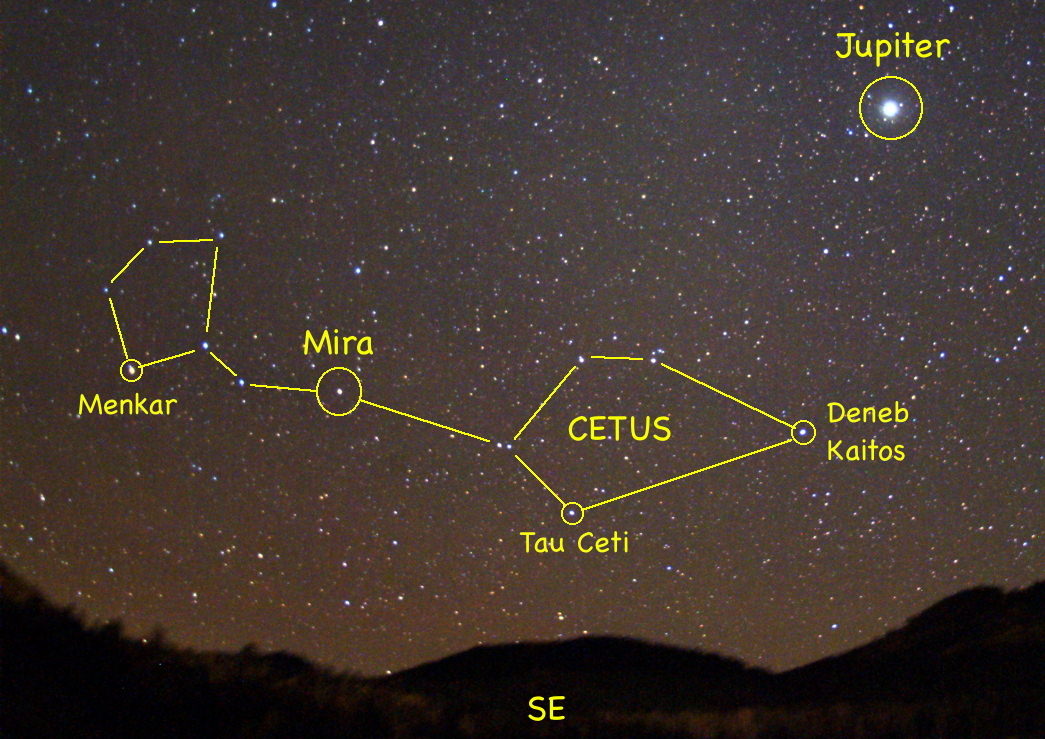

Boss is the author of The Crowded Universe, a book on the likelihood of finding life and habitable planets outside of our Solar System, and Looking For Earths, about the race to find new solar systems.