[/caption]

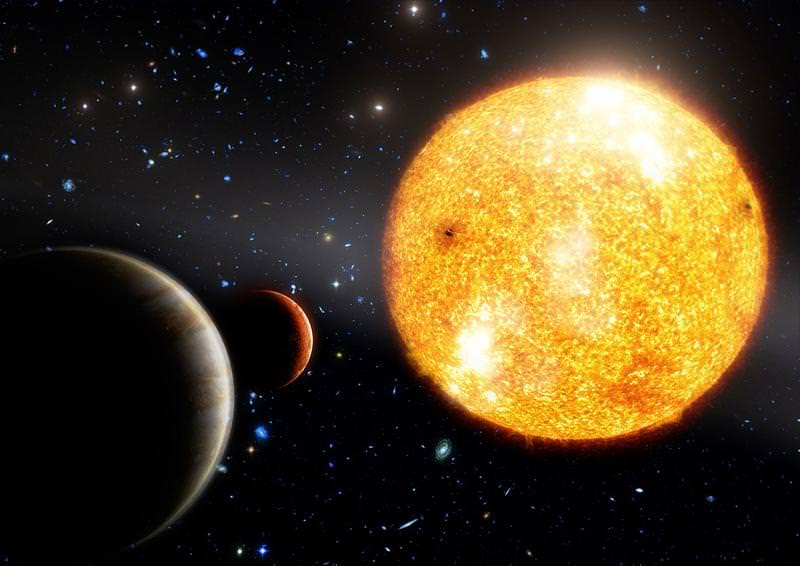

For many of us who grew up listening to Carl Sagan, watching robotic spacecraft travel to other worlds, and indulging in science fiction books and movies, it’s a given: one day we’ll find life somewhere else in the solar system or Universe. But are we being too optimistic? Two researchers say that our hopes and expectations of finding ET might be based more on optimism than scientific evidence, and the recent discoveries of exoplanets that might be similar to Earth are probably getting everyone’s hopes up too high.

Astrophysicist Edwin Turner from Princeton and researcher David Spiegel from the Institute for Advanced Study say the idea that life has or could arise in an another Earth-like environment has only a small amount of supporting evidence, most of it extrapolated from what is known about abiogenesis, or the emergence of life, on early Earth. Their research says the expectations of life cropping up on exoplanets are largely based on the assumption that it would or will happen if the same conditions as Earth exist elsewhere.

Using a Bayesian analysis — which weighs how much of a scientific conclusion stems from actual data and how much comes from the prior assumptions of the scientist — the duo concluded that current knowledge about life on other planets suggests Earth might be a cosmic aberration, where life took shape unusually fast and furious. If so, then the chances of the average terrestrial planet hosting life would be low.

“Fossil evidence suggests that life began very early in Earth’s history and that has led people to determine that life might be quite common in the universe because it happened so quickly here, but the knowledge about life on Earth simply doesn’t reveal much about the actual probability of life on other planets,” Turner said.

So, if a scientist starts out assuming that the chances of life existing on another planet is as large as on Earth, then their scientific results will be presented in a way that supports that likelihood, Turner said.

“Information about that probability comes largely from the assumptions scientists have going in, and some of the most optimistic conclusions have been based almost entirely on those assumptions,” he said.

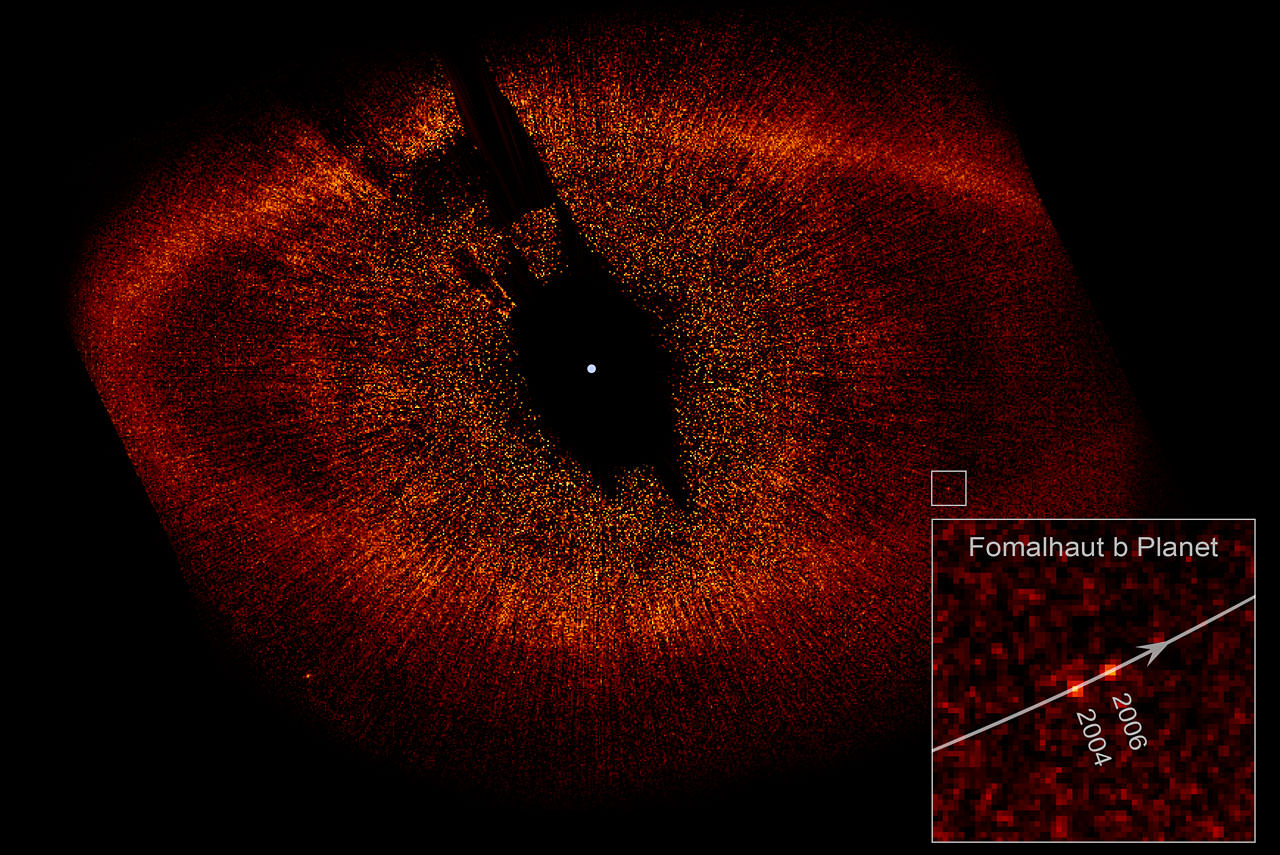

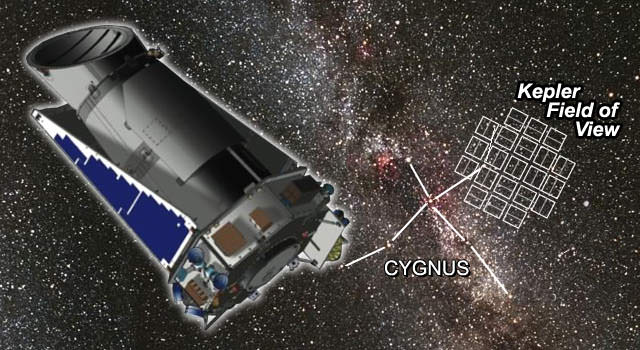

Therefore, with all the exoplanets being found, and as our discoveries have become more and more enticingly Earth-like, these planets have our knowledge of life on Earth projected onto them, the researchers said.

How does an exoplanet researcher feel about this? Turner and Spiegel found a sympathetic soul in Joshua Winn from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who said that the two cast convincing doubt on a prominent basis for expecting extraterrestrial life.

“There is a commonly heard argument that life must be common or else it would not have arisen so quickly after the surface of the Earth cooled,” Winn said. “This argument seems persuasive on its face, but Spiegel and Turner have shown it doesn’t stand up to a rigorous statistical examination — with a sample of only one life-bearing planet, one cannot even get a ballpark estimate of the abundance of life in the universe.

It is true that science is about facts — not about what your gut feelings are. But there’s a strong argument that we need inspiration to do the best, most engaging science. Writer Andrew Zimmerman Jones blogged today at PBS about how many scientists were spurred to follow their careers by reading science fiction when they were young.

“The finest science fiction is inspired by the same thing that has inspired the greatest science discoveries throughout the ages: optimism for the future,” wrote Jones.

And perhaps that is what is mostly behind our hopes for finding ET: optimism for the future of the human race, that we really could one day travel to other worlds, and find new friends — “to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no one has gone before…”

Turner and Spiegel do say they are not making judgments, but just analyzing existing data that suggests the debate about the existence of life on other planets is framed largely by the prior assumptions of the participants.

“It could easily be that life came about on Earth one way, but came about on other planets in other ways, if it came about at all,” Turner said. “The best way to find out, of course, is to look. But I don’t think we’ll know by debating the process of how life came about on Earth.”