[/caption]

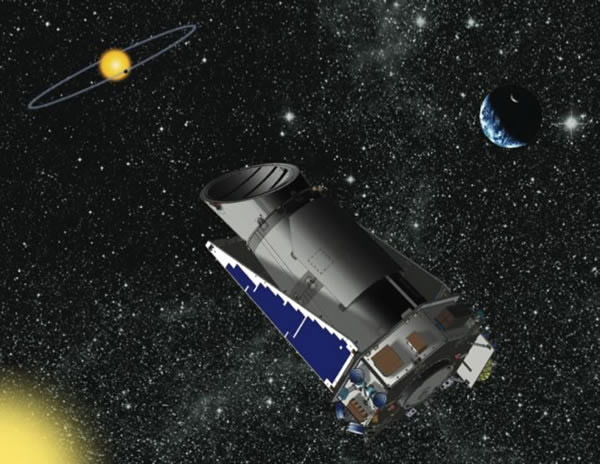

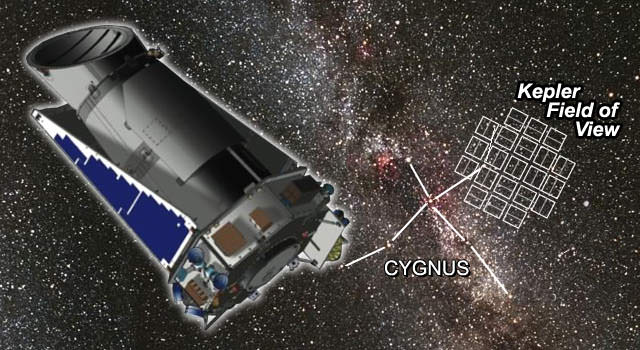

Hot on the heels of confirming one Kepler planet, the Hobby-Eberly Telescope announces the confirmation of another planet. Another observatory, the Nordic Optical Telescope, confirms its first Kepler planet as well, this one as part of a binary system and providing new insights that may force astronomers to revisit and revise estimations on properties of other extrasolar planets.

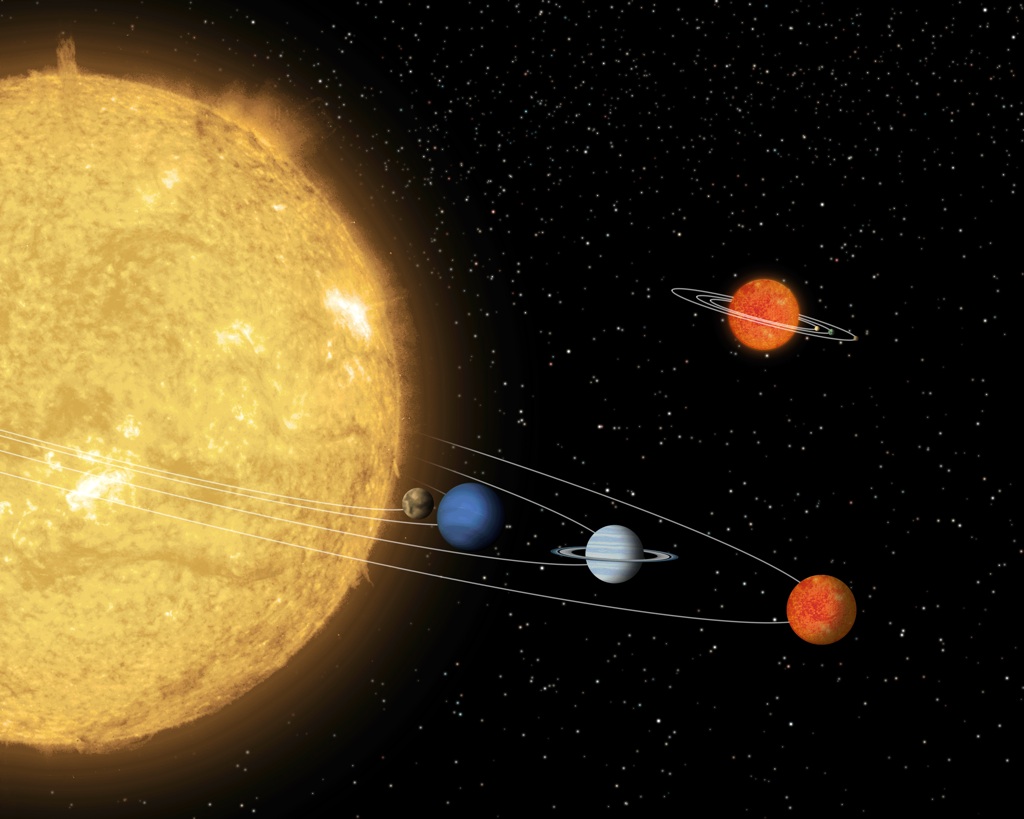

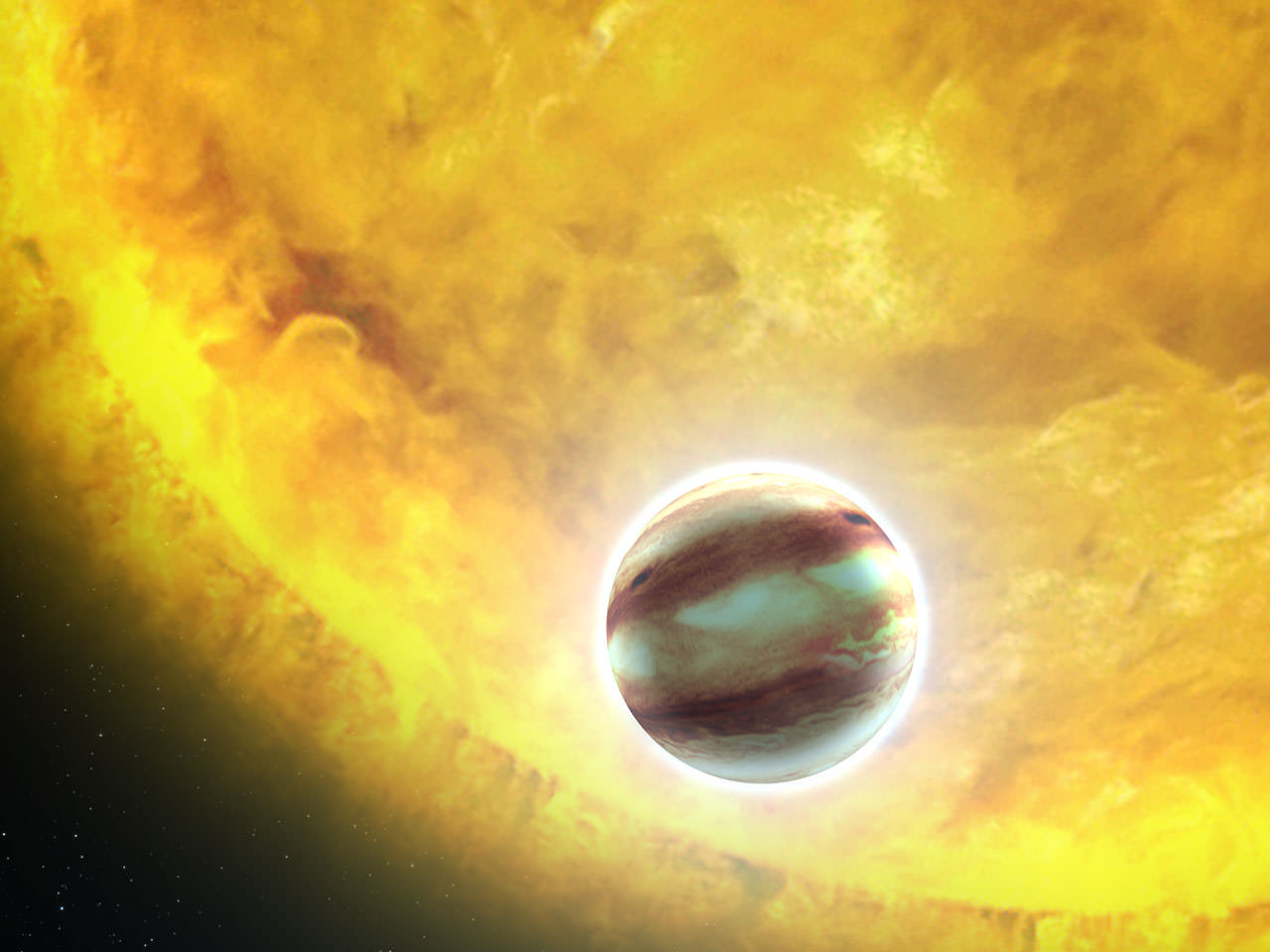

The first reported of these planets was the announcement from the Nordic Optical Telescope of the confirmation of Kepler 14b. The team estimates the planet to be eight times the mass of Jupiter. It orbits its parent star in a short 7 days, putting this object into the class of hot Jupiters. As noted above, the star is in a binary system with the second star taking some 2,800 years to complete one orbit.

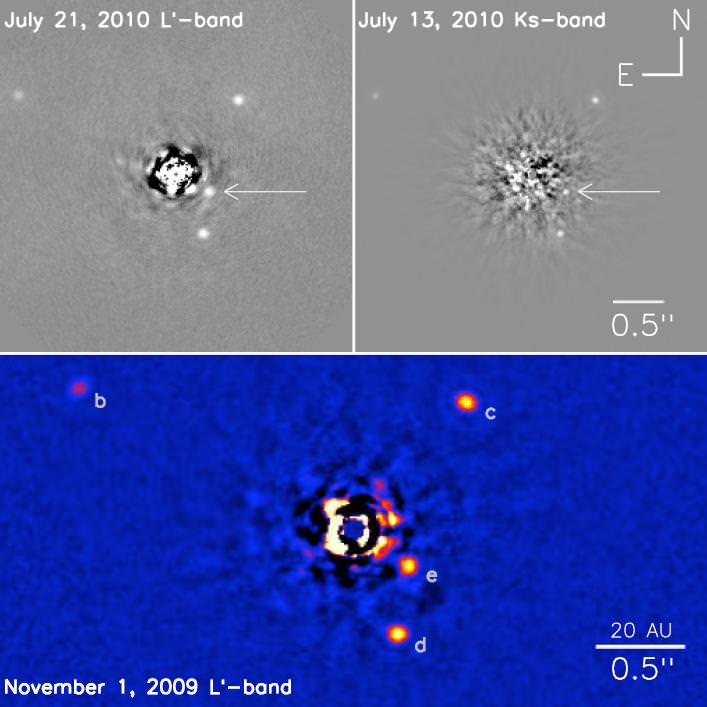

In the announcement the team analyzed the data taking into consideration an effect that has been left out of previous studies of extrasolar planets. The team found that the glare from the nearby star in the binary orbit spilled over onto the image of the star around which the planet orbited. This extra light would dilute the eclipse caused by the planet and subsequently, changed the estimations of the planets properties. The team reported that not correcting for this light pollution, “leads to an underestimate of the radius and mass of the planet by 10% and 60%, respectively.” While this consideration would only apply for planets orbiting stars that were in binary systems, or line of sight double stars, the Kepler 14 system did not appear to be a binary system without high resolution imaging from the Palomar Observatory. This begs the question of whether or not any of the other 500+ known extrasolar planets are in similar systems that have not yet been resolved and whether their parameters may need revision.

The next planet, reported at the end of July, has been dubbed Kepler 17b. Again, this planet falls into the category of Hot Jupiters, although this one is only two and a half time times the mass of Jupiter. It orbits a star very similar the Sun in mass and radius, although expected to be somewhat younger. The observations of the star outside of planetary transits revealed a good deal of activity with temporary dips that did not persist on a regular basis like the signal from the planet. Such variance is likely due to stellar activity and Sunspots and allowed the team to reveal more information about the planet.

Because the planet could also eclipse starspots, it created a stroboscopic effect and the team confirmed the planet orbits in the same direction as the star spins. This is notable since several planets are known to have retrograde orbits.