[/caption]

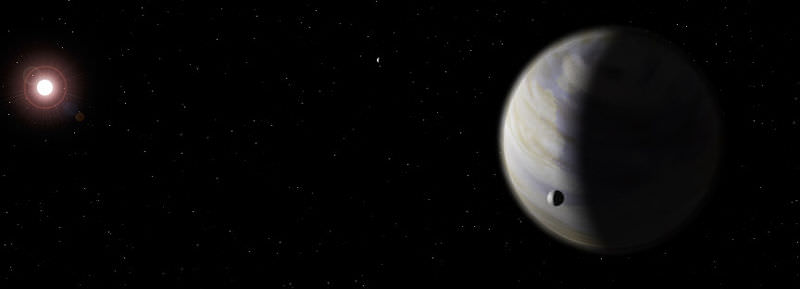

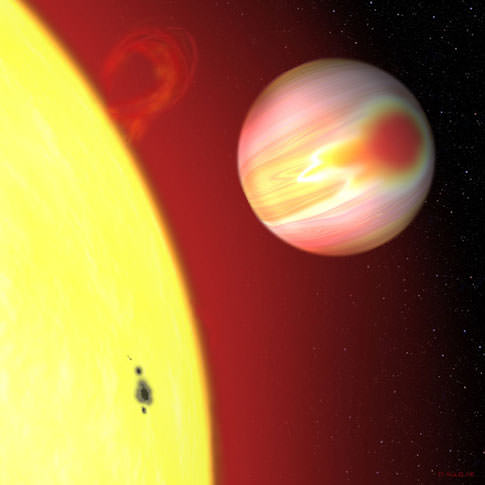

When last we checked in on Gliese 581d, a team from the University of Paris had suggested that the popular exoplanet, Gliese 581d may be habitable. This super-Earth found itself just on the edge of the Goldilocks zone which could make liquid water present on the surface under the right atmospheric conditions. However, the team’s work was based on one dimensional simulations of a column of hypothetical atmospheres on the day side of the planet. To have a better understanding of what Gliese 581d might be like, a three dimensional simulation was in order. Fortunately, a new study from the same team has investigated the possibility with just such an investigation.

The new investigation was called for because Gliese 581d is suspected to be tidally locked, much like Mercury is in our own solar system. If so, this would create a permanent night side on the planet. On this side, the temperatures would be significantly lower and gasses such as CO2 and H2O may find themselves in a region where they could no longer remain gaseous, freezing into ice crystals on the surface. Since that surface would never see the light of day, they could not be heated and released back into the atmosphere, thereby depleting the planet of greenhouse gasses necessary to warm the planet, causing what astronomers call an “atmospheric collapse.”

To conduct their simulation the team assumed that the climate was dominated by the greenhouse effects of CO2 and H2O since this is true for all rocky planets with significant atmospheres in our solar system. As with their previous study, they performed several iterations, each with varying atmospheric pressures and compositions. For atmospheres less than 10 bars, the simulations suggested that the atmosphere would collapse, either on the dark side of the planet, or near the poles. Past this, the effects of greenhouse gasses prevented the freezing of the atmosphere and it became stable. Some ice formation still occurred in the stable models where some of the CO2 would freeze in the upper atmosphere, forming clouds in much the same way it does on Mars. However, this had a net warming effect of ~12°C.

In other simulations, the team added in oceans of liquid water which would help to moderate the climate. Another effect of this was that the vaporization of water from these oceans also produced warming as it can serve as a greenhouse gas, but the formation of clouds could decrease the global temperature since water clouds increase the albedo of the planet, especially in the red region of the spectra which is the most prevalent form of light from the parent star, a red dwarf. However, as with models without oceans, the tipping point for stable atmospheres tended to be around 10 bars of pressure. Under that, “cooling effects dominated and runaway glaciation occurred, followed by atmospheric collapse.” Above 20 bars, the additional trapping of heat from the water vapor significantly increased temperatures compared to an entirely rocky planet.

The conclusion is that Gliese 581d is potentially habitable. The potential for surface water exists for a “wide range of plausible cases”. Ultimately, they all depend on the precise thickness and composition of any atmosphere. Since the planet does not transit the star, spectral analysis through transmission of starlight through the atmosphere will not be possible. Yet the team suggests that, since the Gliese 581 system is relatively close to Earth (only 20 lightyears), it may be possible to observe the spectra directly in the infrared portion of the spectra using future generations of instruments. Should the observations match the synthetic spectra predicted for the various habitable planets, this would be taken as strong evidence for the habitability of the planet.