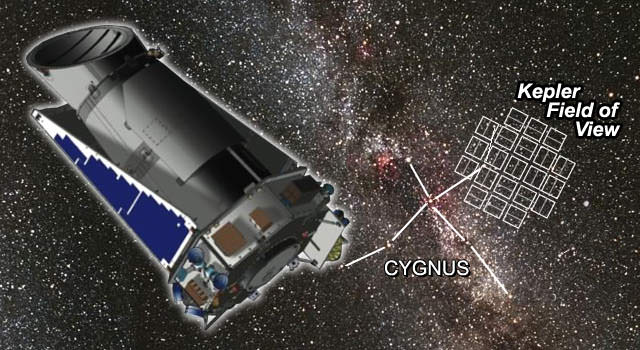

This artist’s concept shows the smallest star known to host a planet. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

In May 2009, astronomers were jubilant: finally, an extra solar planet had been found by using the method of astrometry. That’s great, except, they may not have found a planet after all. Researchers from JPL reported they found a Jupiter-like planet around a star smaller than our sun. But follow-up observations of the star VB10 are coming up empty. “The planet is not there,” said Jacob Bean from the Georg-August University in Gottingen, Germany, who used a different and more successful approach to look for exoplanets, radial velocity.

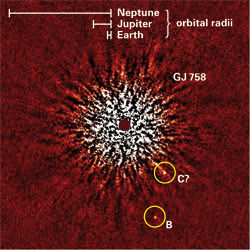

Astrometry measures the side-to-side motion of a star on the sky to see whether any unseen bodies might be orbiting it. Using this method is difficult and requires very precise measurements over long periods of time. Using astrometry to look for exoplanets has been around for 50 years, but it hadn’t bagged a verified exoplanet – until, astronomers thought, earlier this year. A team of researchers announced an exoplanet, six times more massive than Jupiter, orbiting a star about one-thirteenth the mass of the Sun, using a telescope at the Palomar Observatory in southern California (S. Pravdo and S. Shaklan Astrophys. J. 700, 623–632; 2009).

“This method is optimal for finding solar-system configurations like ours that might harbor other Earths,” astronomer Steven Pravdo of JPL said in May. “We found a Jupiter-like planet at around the same relative place as our Jupiter, only around a much smaller star. It’s possible this star also has inner rocky planets. And since more than seven out of 10 stars are small like this one, this could mean planets are more common than we thought.”

But using different methods, other astronomers aren’t finding anything.

“We would definitely have seen a significant amount of variation in our data if [the planet] was there,” said Bean, quoted in the online Nature News. Bean has submitted a paper to the Astrophysical Journal.

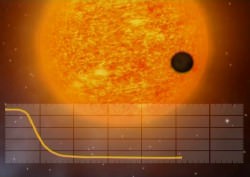

Radial velocity, which has found most of the extrasolar planets so far, looks for shifts in the lines of a star’s absorption spectrum to track its motion towards and away from Earth, which would be caused by the influence of a planet.

Pravdo says that Bean and his colleagues “may be correct, but there is hyperbole in their rejection of our candidate planet.” Bean’s paper, for instance, only rules out the presence of any planet that is at least three times more massive than Jupiter, says Pravdo, adding that the work “limits certain orbits for possible planets but not all planets.”

Astronomers expect astrometry to work much better above the distorting effects of the atmosphere. Two space missions in the works — the European Space Agency’s GAIA, due to launch in 2012, and NASA’s proposed SIM-lite (Space Interferometry Mission) will use the technique to search for planets as small as Earth around Sun-like stars. Astrometry potentially can yield the mass of a planet, whereas radial velocity only puts a lower limit on it.

Bean admits that astronomers might one day find a planet around VB10 if they scrutinize the star long and hard enough.

Source: Nature News