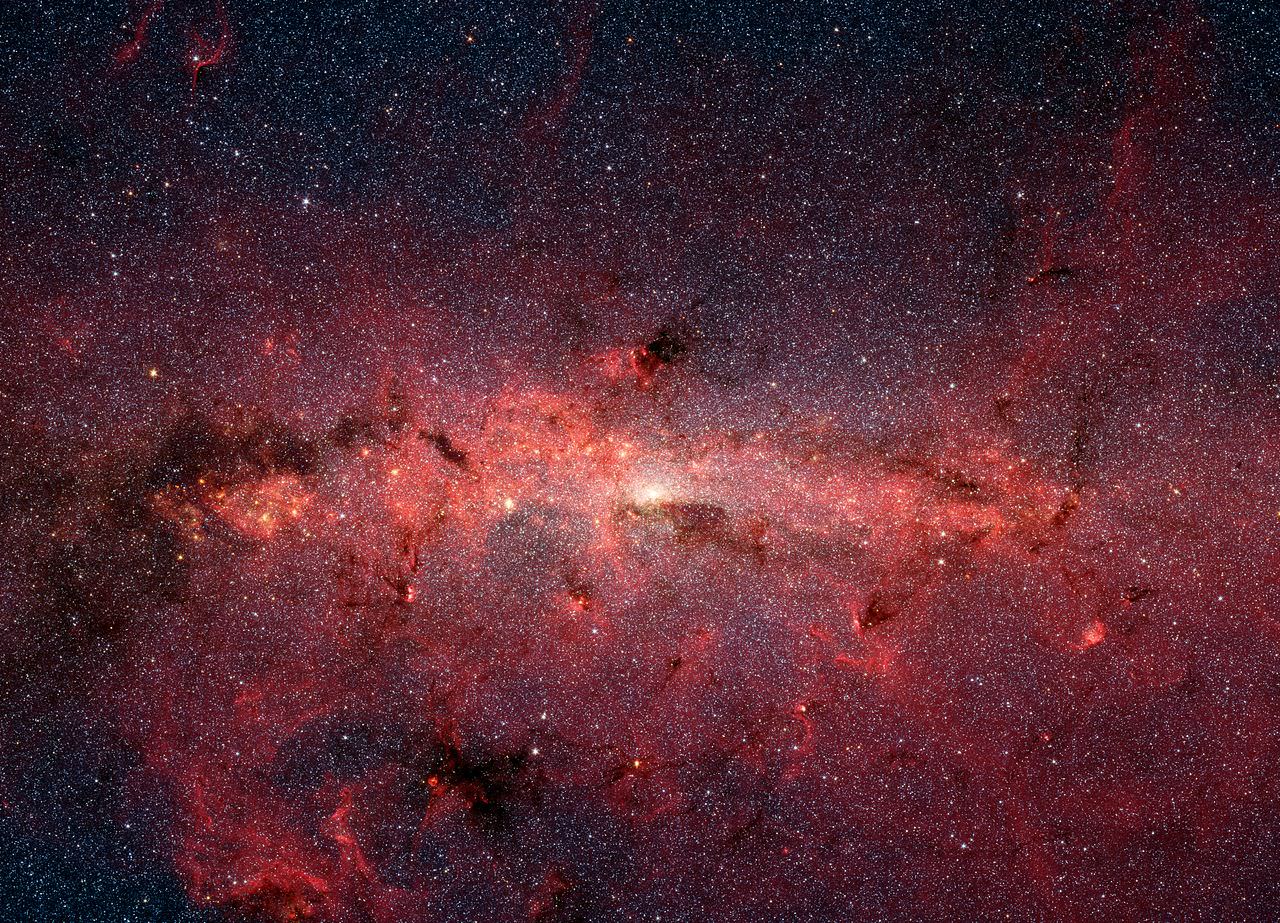

In 1961, famed astronomer and astrophysicist Frank Drake formulated an equation for estimating the number of extraterrestrial civilizations in our galaxy at any given time. Known as the “Drake Equation“, this formula was a probabilistic argument meant to establish some context for the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). Of course, the equation was theoretical in nature and most of its variables are still not well-constrained.

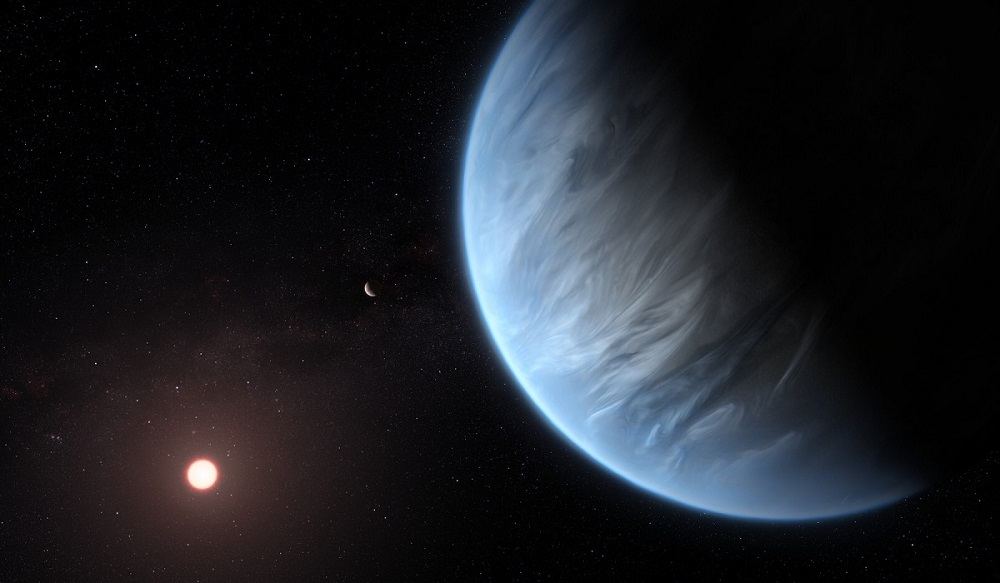

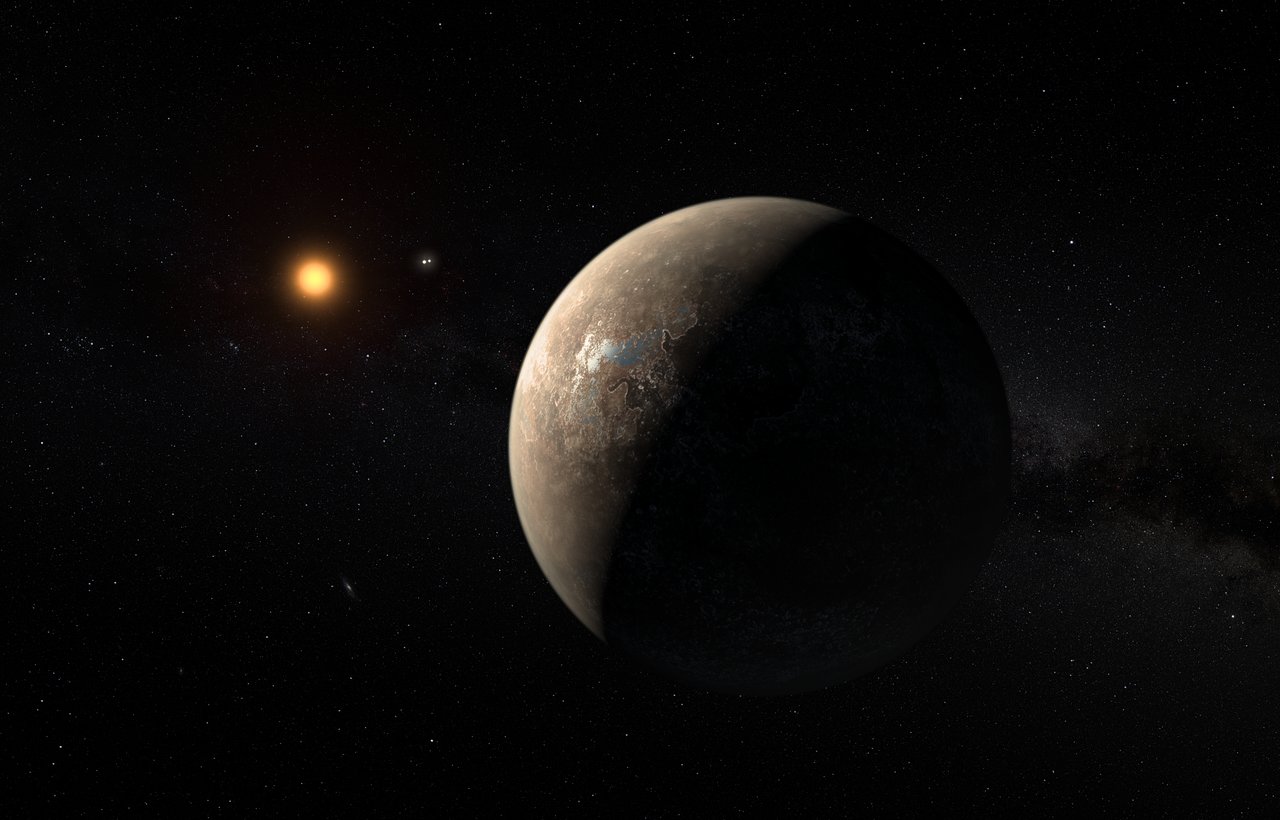

For instance, while astronomers today can speak with confidence about the rate at which new stars form, and the likely number of stars that have exoplanets, they can’t begin to say how many of these planets are likely to support life. Luckily, Professor David Kipping of Columbia University recently performed a statistical analysis that indicates that a Universe teeming with life is “the favored bet.”

Continue reading “What are the Odds of Life Emerging on Another Planet?”