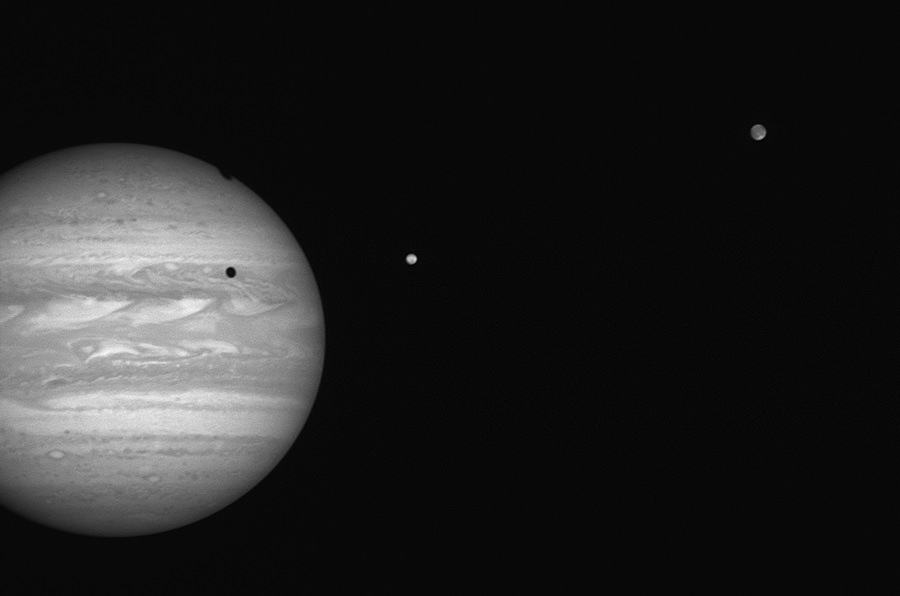

Watching the inky-black shadow of a Jovian moon slide across the cloud-tops of Jupiter is an unforgettable sight. Two is always better than one, and as the largest planet in our solar system heads towards opposition on March 8th, so begins the first of two seasons of double shadow transits for 2016. Continue reading “Double Shadow Transit Season for the Jovian Moons Begins”

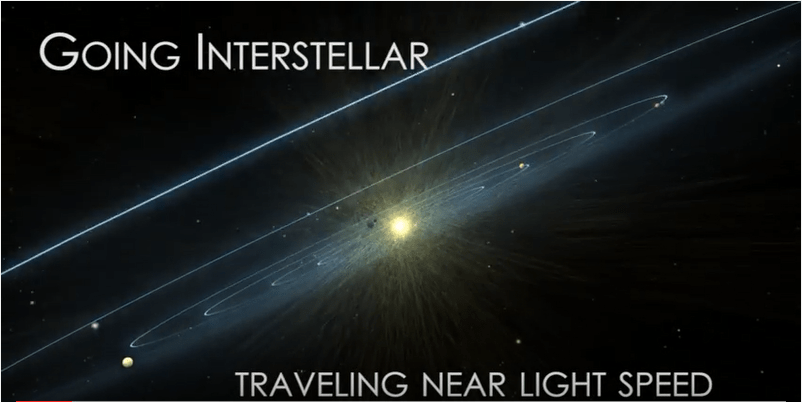

NASA Thinks There’s a Way to Get to Mars in 3 Days

We’ve achieved amazing things by using chemical rockets to place satellites in orbit, land people on the Moon, and place rovers on the surface of Mars. We’ve even used ion drives to reach destinations further afield in our Solar System. But reaching other stars, or reducing our travel time to Mars or other planets, will require another method of travel. One that can approach relativistic speeds.

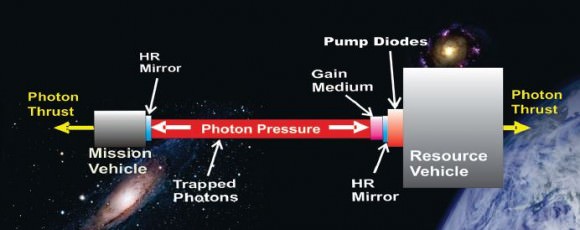

The system is called DEEP IN, or Directed Propulsion for Interstellar Exploration. The general idea is that we have achieved relativistic speeds in the laboratory, but haven’t taken that technology—which is electromagnetic in nature, rather than chemical—and used it outside of the laboratory. In short, we can propel individual particles to near light speed inside particle accelerators, but haven’t expanded that technology to the macro level.

Directed Energy Propulsion differs from rocket technology in a fundamental way: the propulsion system stays at home, and the craft doesn’t carry any fuel or propellant. Instead, the craft would carry a system of reflectors, which would be struck with an aimed stream of photons, propelling the craft forward. And the whole system is modular and scalable.

If that’s not tantalizing enough, the system can also be used to deflect hazardous space debris, and to detect other technological civilizations. As talked about in this paper, detecting these types of systems in use by other civilizations may be our best hope for discovering those civilizations.

There’s a roadmap for using this system, and it starts small. At first, DEEP IN would be used to launch small cube satellites. The feedback from this phase would then inform the next step, which would be to test a unit for defending the ISS from space debris. From then, the systems would meet goals of increasing complexity, from launching satellites to LEO (Low-Earth Orbit) and GEO (Geostationary Orbit), all the way up to asteroid deflection and planetary defense. After that, relativistic drives capable of interstellar travel is the goal.

There are lots of questions still to be answered of course, like what happens when a vehicle at near light-speed hits a tiny meteorite. But those questions will be asked and answered as the system is developed and its capabilities grow.

Obviously, DEEP IN has the potential to bring other stars into reach. This system could deliver probes to some of the more promising exo-planets, and give humanity its first detailed look at other solar systems. If DEEP IN can be successfully scaled up, as Lubin says, then it will be a transformational technology.

Here’s a longer video of Dr. Lubin explaining DEEP IN in greater depth and detail: http://livestream.com/viewnow/niac2015seattle

Here’s the website for the University of California Santa Barbara Experimental Cosmology Group: http://www.deepspace.ucsb.edu/

ExoMars 2016 Orbiter and Lander Mated for March Launch

Earth’s lone mission to the Red Planet this year has now been assembled into launch configuration and all preparations are currently on target to support blastoff from Baikonur at the opening of the launch window on March 14, 2016.

The ambitious ExoMars 2016 mission is comprised of a pair of European spacecraft named the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) and the Schiaparelli lander, built and funded by the European Space Agency (ESA). Continue reading “ExoMars 2016 Orbiter and Lander Mated for March Launch”

Does Antarctica Have A Hidden Layer Of Meteorites Below Its Surface?

In the category of why-didn’t-I think-of-that ideas, Dr. Geoffrey Evatt and colleagues from the University of Manchester struck upon a brilliant hypothesis: that a layer of iron meteories might lurk just below the surface of the Antarctic ice. He’s the lead author of a recent paper on the topic published in the open-access journal, Nature Communications.

Remote Antarctica makes one of the best meteorite collecting regions on the planet. Space rocks have been accumulating there for millennia preserved in the continent’s cold, desert-like climate. While you might think it’s a long and expensive way to go to hunt for meteorites, it’s still a lot cheaper than a sample return mission to the asteroid belt. Meteorites fall and become embedded in ice sheets within the continent’s interior. As that ice flows outward toward the Antarctic coastlines, it pushes up against the Transantarctic Mountains, where powerful, dry winds ablate away the ice and expose their otherworldly cargo.

Layer after layer, century after century, the ice gets stripped away, leaving rich “meteorite stranding zones” where hundreds of space rocks can be found within an area the size of a soccer field. Since most meteorites arrive on Earth coated in a black or brown fusion crust from their searing fall through the atmosphere, they contrast well against the white glare of snow and ice. Scientists liken it to a conveyor belt that’s been operating for the past couple million years.

Scientists form snowmobile posses and buzz around the ice fields picking them up like candy eggs on Easter morning. OK, it’s not that easy. There’s much planning and prep followed by days and nights of camping in bitter cold with high winds tearing at your tent. Expeditions take place from October through early January when the Sun never sets.

The U.S. under ANSMET (Antarctic Search for Meteorites, a Case Western Reserve University project funded by NASA), China, Japan and other nations run programs to hunt and collect the precious from the earliest days of the Solar System before they find their way to the ocean or are turned to dust by the very winds that revealed them in the first place. Since systematic collecting began in 1976, some 34,927 meteorites have been recovered from Antarctica as of December 2015.

Meteorites come in three basic types: those made primarily of rock; stony-irons comprised of a mixture of iron and rock; and iron-rich. Since collection programs have been underway, Antarctic researchers have uncovered lots of stony meteorites, but meteorites either partly or wholly made of metal are scarce compared to what’s found in other collecting sites around the world, notably the deserts of Africa and Oman. What gives?

Dr. Evatt and colleagues had a hunch and performed a simple experiment to arrive at their hypothesis. They froze two meteorites of similar size and shape — a specimen of the Russian Sikhote-Alin iron and NWA 869, an ordinary (stony) chondrite — inside blocks of ice and heated them using a solar-simulator lamp. As expected, both meteorites melted their way down through the ice in time, but the iron meteorite sank further and faster. I bet you can guess why. Iron or metal conducts heat more efficiently than rock. Grab a metal camera tripod leg or telescope tube on a bitter cold night and you’ll know exactly what I mean. Metal conducts the heat away from your hand far better and faster than say, a piece of wood or plastic.

The researchers performed many trials with the same results and created a mathematical model showing that Sun-driven burrowing during the six months of Antarctic summer accounted nicely for the lack of iron meteorites seen in the stranding zones. Co-author Dr. Katherine Joy estimates that the fugitive meteorites are trapped between about 20-40 inches (50-100 cm) beneath the ice.

Who wouldn’t be happy to find this treasure? Dr. Barbara Cohen is seen with a large meteorite from the Antarctic’s Miller Range. Credit: Antarctic Search for Meteorites ProgramYou can imagine how hard it would be to dig meteorites out of Antarctic ice. It’s work enough to mount an expedition to pick up just what’s on the surface.

With the gauntlet now thrown down, who will take up the challenge? The researchers suggests metal detectors and radar to help locate the hidden irons. Every rock delivered to Earth from outer space represents a tiny piece of a great puzzle astronomers, chemists and geologist have been assembling since 1794 when German physicist Ernst Chladni published a small book asserting that rocks from space really do fall from the sky.

Like the puzzle we leave unfinished on the tabletop, we have a picture, still incomplete, of a Solar System fashioned from the tiniest of dust motes in the crucible of gravity and time.

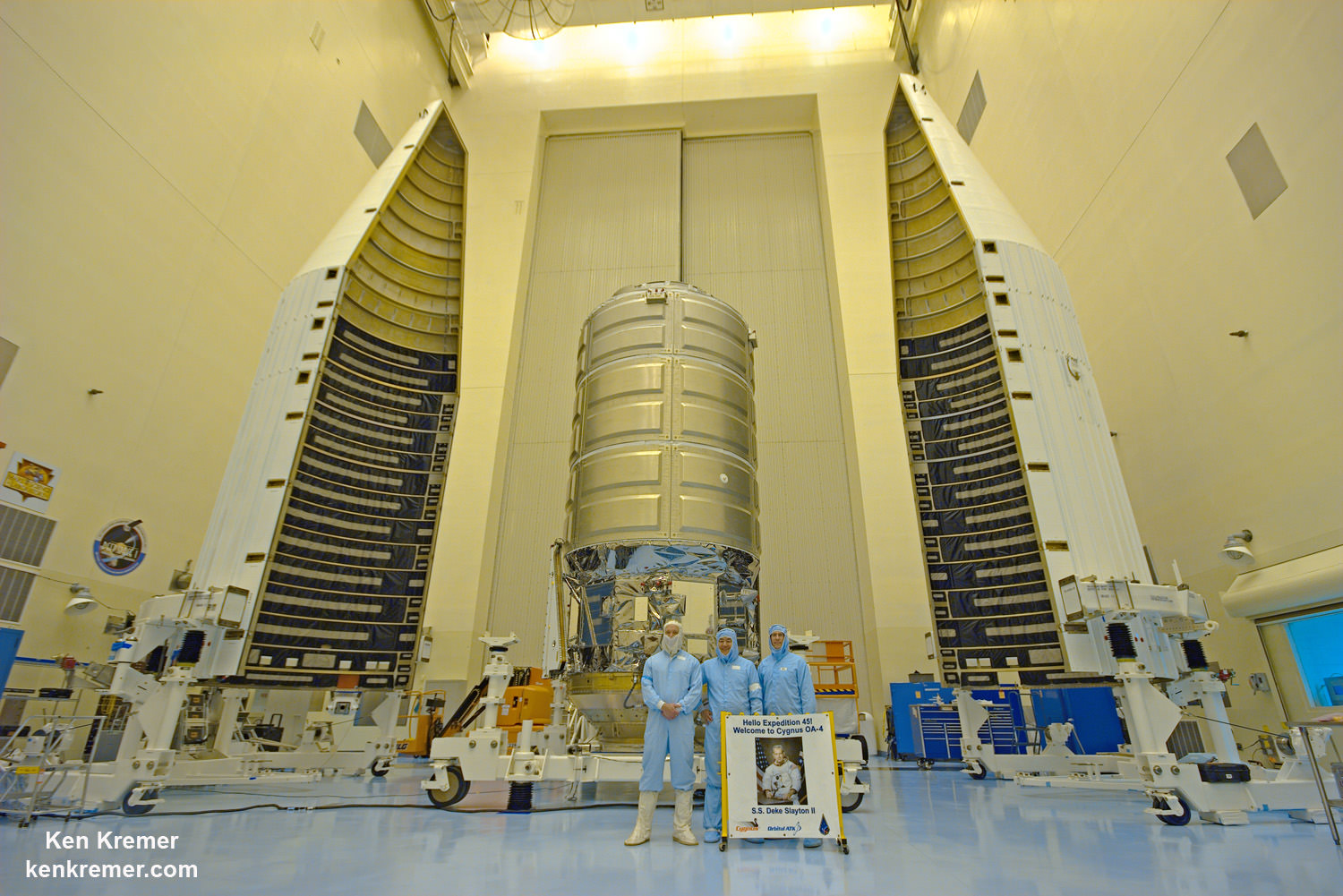

Commercial Cygnus Cargo Freighter Departs ISS After Resuming US Resupply Runs

A commercial Cygnus cargo freighter departed the International Space Station (ISS) this morning (Feb. 19) after successfully resuming America’s train of resupply runs absolutely essential to the continued productive functioning of the orbiting science outpost.

NASA astronauts Scott Kelly and Tim Kopra commanded the release of the privately developed Orbital ATK “S.S. Deke Slayton II” Cygnus resupply ship from the snares of the stations Canadian-built robotic arm at 7:26 a.m. EST – while the space station was flying approximately 250 miles (400 km) above Bolivia.

“Honor to give #Cygnus a hand (or arm) in finalizing its mission this morning. Well done #SSDekeSlayton!” Kelly quickly posted to his social media accounts.

The Orbital ATK “S.S. Deke Slayton II” Cygnus craft had arrived at the station with several tons of supplies on Dec. 9, 2015 after blazing to orbit on Dec. 6 atop a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida on the company’s fourth NASA-contracted commercial station resupply mission dubbed CRS-4.

To prepare for today’s release, ground controllers at NASA’s Johnson Space Center first used the station’s 57.7-foot-long (17.6- meter-long) robotic arm, Canadarm2, to unberth Cygnus from its place on the stations Earth-facing port of the Unity module at about 5:38 a.m.

Cygnus came loaded with over three tons of critically needed supplies and research experiments as well as Christmas presents for the astronauts and cosmonauts living and working on the massive orbital lab complex during Expeditions 45 and 46.

Today’s activities were carried live on NASA TV. This brief NASA video shows a few highlights from Cygnus departure:

Altogether, Cygnus spent approximately 72 days attached to the station. During that time the crews unloaded all the research gear for experiments in areas such as biology, biotechnology, and physical and Earth science.

“All good things must come to an end. #Cygnus, your mission was a success! Farewell #SSDekeSlayton,” said Kelly.

Mission controllers at Orbital ATK’s Dulles, VA space operations facility soon commanded Cygnus to fire its thrusters to gradually maneuver away from the station.

Before departure, the crew had loaded Cygnus back up with about 3000 pounds of trash for disposal.

On Saturday, after the spacecraft is far away from the station, controllers will fire the engines twice to pushing the vehicle into Earth’s atmosphere for a fiery reentry where it will harmlessly burn up over the Pacific Ocean.

Meanwhile, Kelly himself will also be departing the ISS in about ten days when his historic ‘1 Year ISS Mission’ concludes on March 1, when he returns to Earth on a Russian Soyuz capsule along with his cosmonaut crewmates Mikhail Kornienko and Sergey Volkov.

December’s arrival of the Orbital ATK Cygnus CRS-4 cargo freighter – also known as OA-4 – represented the successful restart of American’s critically needed cargo missions to the ISS following a pair of launch failures by both of NASA’s cargo providers – Orbital ATK and SpaceX – over the past year and a half. It was the first successful US cargo delivery mission in some 8 months.

Cygnus was named the ‘SS Deke Slayton II’ in memory of Deke Slayton, one of the America’s original seven Mercury astronauts. He was a member of the Apollo Soyuz Test Flight. Slayton was also a champion of America’s commercial space program.

CRS-4 counts as the first flight of Cygnus on an Atlas and the first launch to the ISS using an Atlas booster.

This is also the first flight of the enhanced, longer Cygnus, measuring 5.1 meters (20.5 feet) tall and 3.05 meters (10 feet) in diameter, sporting a payload volume of 27 cubic meters.

“The enhanced Cygnus PCM is 1.2 meters longer, so it’s about 1/3 longer,” Frank DeMauro, Orbital ATK Vice President for Human Spaceflight Systems Programs, said in an exclusive interview with Universe Today.

This Cygnus also carried its heaviest payload to date since its significantly more voluminous than the original shorter version.

“It can carry about 50% more payload,” DeMauro told me.

“This Cygnus will carry more payload than all three prior vehicles combined,” former NASA astronaut Dan Tani elaborated.

The total payload packed on board amounted to 3513 kilograms (7745 pounds), including science investigations, crew supplies, vehicle hardware, spacewalk equipment and computer resources.

Among the contents are science equipment totaling 846 kg (1867 lbs.), crew supplies of 1181 kg (2607 lbs.), and spacewalk equipment of 227 kg (500 lbs.).

Orbital ATK holds a Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contract from NASA worth $1.9 Billion to deliver 20,000 kilograms of research experiments, crew provisions, spare parts and hardware for eight Cygnus cargo delivery flights to the ISS.

Orbital ATK has contracted a second Cygnus to fly on an Atlas on the OA-6 mission, currently slated for liftoff around March 22, 2016. Liftoff was delayed about two weeks to decontaminate an infestation of mold found in cargo already packed on the Cygnus.

NASA has also contracted with Orbital ATK to fly three additional missions through 2018. Orbital also recently was awarded six additional cargo missions by NASA as part of the CRS-2 procurement.

Orbital ATK hopes to resume Cygnus cargo launches with their own re-engined Antares rocket from NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia this summer.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

Hubble Directly Measures Rotation of Cloudy ‘Super-Jupiter’

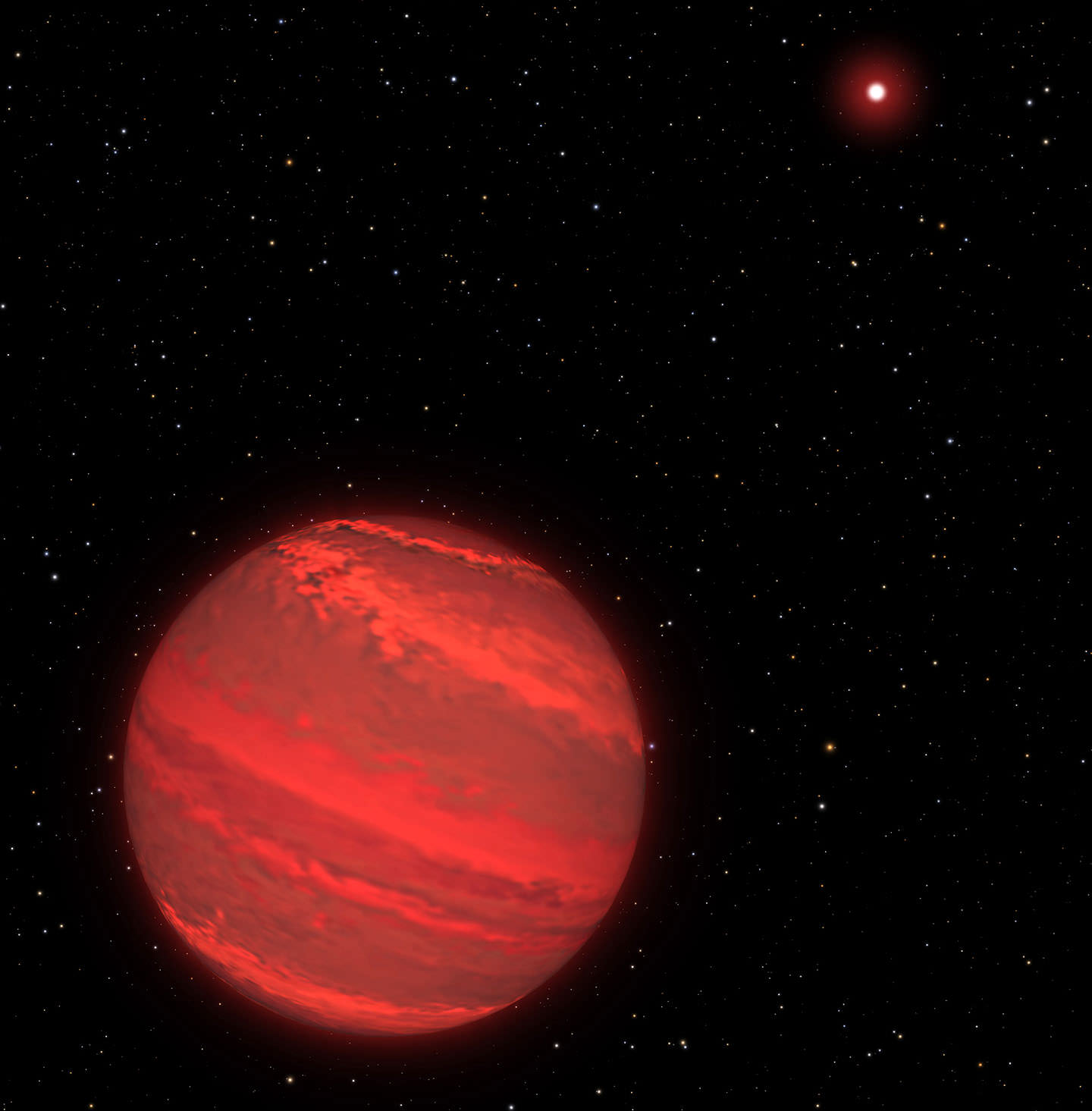

Astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope have measured the rotation rate of an extreme exoplanet 2M1207b by observing the varied brightness in its atmosphere. This is the first measurement of the rotation of a massive exoplanet using direct imaging.

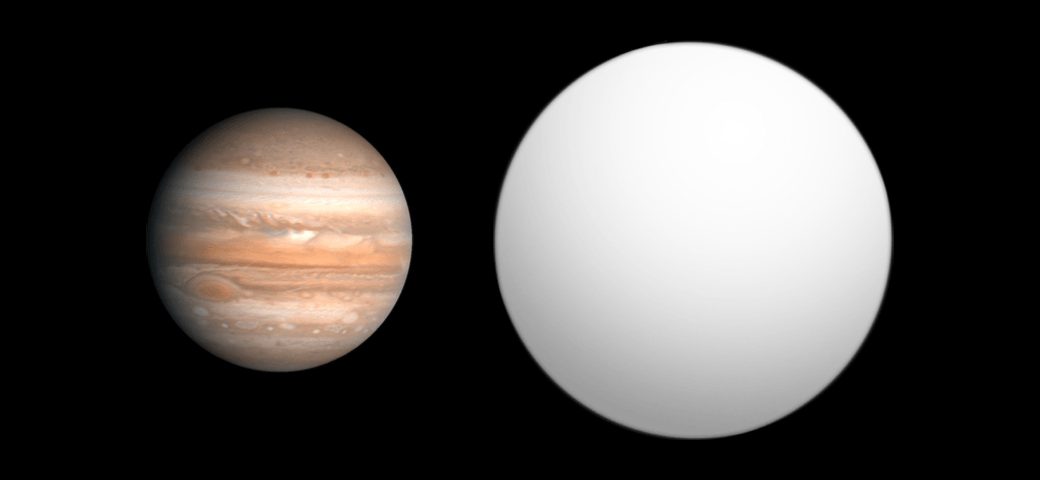

Little by little we’re coming to know at least some of the 2,085 exoplanets discovered to date more intimately despite their great distances and proximity to the blinding light of their host stars. 2M1207b is about four times more massive than Jupiter and dubbed a “super-Jupiter”. Super-Jupiters fill the gap between Jupiter-mass planets and brown dwarf stars. They can be up to 80 times more massive than Jupiter yet remain nearly the same size as that planet because gravity compresses the material into an ever denser, more compact sphere.

2M1207b lies 170 light years from Earth and orbits a brown dwarf at a distance of 5 billion miles. By contrast, Jupiter is approximately 500 million miles from the sun. You’ll often hear brown dwarfs described as “failed stars” because they’re not massive enough for hydrogen fusion to fire up in their cores the way it does in our sun and all the rest of the main sequence stars.

Researchers used Hubble’s exquisite resolution to precisely measure the planet’s brightness changes as it spins and nailed the rotation rate at 10 hours, virtually identical to Jupiter’s. While it’s fascinating to know a planet’s spin, there’s more to this extraordinary exoplanet. Hubble data confirmed the rotation but also showed the presence of patchy, “colorless” (white presumably) cloud layers. While perhaps ordinary in appearance, the composition of the clouds is anything but.

The planet appears bright in infrared light because it’s young (about 10 million years old) and still contracting, releasing gravitational potential energy that heats it from the inside out. All that extra heat makes 2M1207b’s atmosphere hot enough to form “rain” clouds made of vaporized rock. The rock cools down to form tiny particles with sizes similar to those in cigarette smoke. Deeper into the atmosphere, iron droplets are forming and falling like rain, eventually evaporating as they enter the lower levels of the atmosphere.

“So at higher altitudes it rains glass, and at lower altitudes it rains iron,” said Yifan Zhou of the University of Arizona, lead author on the research paper in a recent Astrophysical Journal. “The atmospheric temperatures are between about 2,200 to 2,600 degrees Fahrenheit.” Every day’s a scorcher on 2M1207b.

Both Jupiter and Saturn also emit more heat than they receive from the sun because they too are still contracting despite being 450 times older. The bigger you are, the slower you chill.

All the planets in our Solar System possess only a fraction of the mass of the Sun. Even mighty Jove is a thousand times less massive. But Mr. Super-Jupiter’s a heavyweight compared to its brown dwarf host, being just 5-7 times less massive. While Jupiter and the rest of the planets formed by the accretion of dust and rocks within a clumpy disk of material surrounding the early Sun, it’s thought 2M1207b and its companion may have formed throughout the gravitational collapse of a pair of separate disks.

This super-Jupiter will an ideal target for the James Webb Space Telescope, a space observatory optimized for the infrared scheduled to launch in 2018. With its much larger mirror — 21-feet (6.5-meters) — Webb will help astronomers better determine the exoplanet’s atmospheric composition and created more detailed maps from brightness changes.

Teasing out the details of 2M1207b’s atmosphere and rotation introduces us to a most alien world the likes of which never evolved in our own Solar System. I feel like I’m aboard the Starship Enterprise visiting far-flung worlds. Only this is better. It’s real.

Weekly Space Hangout – Feb. 19, 2016: Rebecca Roth

Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Special Guest: Rebecca Roth, Imaging Coordinator & Social Media Specialist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center; responsible for sharing imagery with the media, as well as sharing those images with the public, mainly through social media such as Instagram and Flickr.

Guests:

Morgan Rehnberg (MorganRehnberg.com / @MorganRehnberg )

Kimberly Cartier (@AstroKimCartier )

Dave Dickinson (www.astroguyz.com / @astroguyz)

Jolene Creighton (fromquarkstoquasars.com / @futurism)

Their stories this week:

New X-ray observatory takes to the skies

Hubble Directly Measures Rotation of Cloudy “Super-Jupiter”

Possible Hidden Layer of Meteorites in Antarctica

China to Displace Thousands for New Radio Telescope

Visible light and gravitational waves

We’ve had an abundance of news stories for the past few months, and not enough time to get to them all. So we’ve started a new system. Instead of adding all of the stories to the spreadsheet each week, we are now using a tool called Trello to submit and vote on stories we would like to see covered each week, and then Fraser will be selecting the stories from there. Here is the link to the Trello WSH page (http://bit.ly/WSHVote), which you can see without logging in. If you’d like to vote, just create a login and help us decide what to cover!

We record the Weekly Space Hangout every Friday at 12:00 pm Pacific / 3:00 pm Eastern. You can watch us live on Google+, Universe Today, or the Universe Today YouTube page.

You can also join in the discussion between episodes over at our Weekly Space Hangout Crew group in G+!

We Have Underestimated Our Sun’s Destructive Reach

The Sun has enormous destructive power. Any objects that collide with the Sun, such as comets and asteroids, are immediately destroyed.

But now we’re finding that the Sun has the ability to reach out and touch asteroids at a far greater distance than previously thought. The proof of this came when a team at the University of Hawaii Institute of Astronomy was looking at Near-Earth Objects (NEOs) catalogued by the Catalina Sky Survey, and trying to understand what asteroids might be missing from that survey.

An asteroid is classified as an NEO when, at its closest point to the Sun, it is less than 1.3 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun. We need to know where these objects are, how many of them there are, and how big they are. They’re a potential threat to spacecraft, and to Earth itself.

The Catalina Sky Survey (CSS) detected over 9,000 NEOs in eight years. But asteroids are notoriously difficult to detect. They are tiny points of light, and they’re moving. The team knew that there was no way the CSS could have detected all NEOs, so Dr. Robert Jedicke, a team member from the University of Hawaii Institute of Astronomy, developed software that would tell them what CSS had missed in its survey of NEOs.

This took an enormous amount of work—and computing power—and when it was completed, they noticed a discrepancy: according to their work, there should be over ten times as many objects within ten solar diameters of the Sun as they found. The team had a puzzle on their hands.

The team spent a year verifying their work before concluding that the problem did not lay in their analysis, but in our understanding of how the Solar System works. University of Helsinki scientist Mikael Granvik, lead author of the Nature article that reported these results, hypothesized that their model of the NEO population would better suit their results if asteroids were destroyed at a much greater distance from the sun than previously thought.

They tested this idea, and found that it agreed with their model and with the observed population of NEOs, once asteroids that spent too much time within 10 solar diameters of the Sun were eliminated. “The discovery that asteroids must be breaking up when they approach too close to the Sun was surprising and that’s why we spent so much time verifying our calculations,” commented Dr. Jedicke.

There are other discrepancies in our Solar System between what is observed and what is predicted when it comes to the distribution of small objects. Meteors are small pieces of dust that come from asteroids, and when they enter our atmosphere they burn up and make star-gazing all the more eventful. Meteors exist in streams that come from their parent objects. The problems is, most of the time the streams can’t be matched with their parent object. This study shows that the parent objects must have been destroyed when they got too close to the Sun, leaving behind a stream of meteors, but no apparent source.

There was another surprise in store for the team. Darker asteroids are destroyed at a greater distance from the Sun than lighter ones are. This explains an earlier discovery, which showed that brighter NEOs travel closer to the Sun than darker ones do. If darker asteroids are destroyed at a greater distance from the Sun than their lighter counterparts, then the two must have differing compositions and internal structure.

“Perhaps the most intriguing outcome of this study is that it is now possible to test models of asteroid interiors simply by keeping track of their orbits and sizes. This is truly remarkable and was completely unexpected when we first started constructing the new NEO model,” says Granvik.

Space Farmer Scott Kelly Harvests First ‘Space Zinnias’ Grown Aboard Space Station

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FL – Nearing the final days of his history making one-year-long sojourn in orbit, space farming NASA astronaut Scott Kelly harvested the first ever crop of ‘Space Zinnias’ grown aboard the International Space Station (ISS) on a most appropriate day – Valentine’s Day, Sunday, Feb. 14, 2016.

After enduring an unexpected series of trial and tribulations – including a fearsome attack of ‘space mold’ – Kelly summoned his inner ‘Mark Watney’ and brought the Zinnia’s to life, blossoming in full color and drenched in natural sunlight. See photo above. Continue reading “Space Farmer Scott Kelly Harvests First ‘Space Zinnias’ Grown Aboard Space Station”

Did a Gamma Ray Burst Accompany LIGO’s Gravity Wave Detection?

Last week’s announcement that Gravitational Waves (GW) have been detected for the first time—as a result of the merger of two black holes—is huge news. But now a Gamma Ray Burst (GRB) originating from the same place, and that arrived at Earth 0.4 seconds after the GW, is making news. Isolated black holes aren’t supposed to create GRB’s; they need to be near a large amount of matter to do that.

NASA’s Fermi telescope detected the GRB, coming from the same point as the GW, a mere 0.4 seconds after the waves arrived. Though we can’t be absolutely certain that the two phenomena are from the same black hole merger, the Fermi team calculates the odds of that being a coincidence at only 0.0022%. That’s a pretty solid correlation.

So what’s going on here? To back up a little, let’s look at what we thought was happening when LIGO detected gravitational waves.

Our understanding was that the two black holes orbited each other for a long time. As they did so, their massive gravity would have cleared the area around them of matter. By they time they finished circling each other and merged, they would have been isolated in space. But now that a GRB has been detected, we need some way to account for it. We need more matter to be present.

According to Abraham Loeb, of Harvard University, the missing piece of this puzzle is a massive star—itself the result of a binary star system combining into one—a few hundred times larger than the Sun, that spawned two black holes. A star this size would form a black hole when it exhausted its fuel and collapsed. But why would there be two black holes?

Again, according to Loeb, if the star was rotating at a high enough rate—just below its break up frequency—the star could actually form two collapsing cores in a dumbbell configuration, and hence two black holes. But now these two black holes would not be isolated in space, they would actually be inside a massive star. Or what was left of one. The remnants of the massive star is the missing matter.

When the black holes joined together, an outflow would be generated, which would produce the GRB. Or else the GRB came “from a jet originating out of the accretion disk of residual debris around the BH remnant,” according to Loeb’s paper. So why the 0.4 s delay? This is the time it took the GRB to cross the star, relative to the gravitational waves.

It sounds like a nice tidy explanation. But, as Loeb notes, there are some problems with it. The main question is, why was the GRB so weak, or dim? Loeb’s paper says that “observed GRB may be just one spike in a longer and weaker transient below the GBM detection threshold.”

But was the GRB really weak? Or was it even real? The European Space Agency has their own gamma ray detecting spacecraft, called Integral. Integral was not able to confirm the GRB signal, and according to this paper, the gamma ray signal was not real after all.

As they say in show business, “Stay tuned.”