It’s official: this Thursday, February 11, at 10:30 EST, there will be parallel press conferences at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., in Hannover, Germany, and near Pisa in Italy. Not officially confirmed, but highly probable, is that people running the LIGO gravitational wave detectors will announce the first direct detection of a gravitational wave. The first direct detection of minute distortions of spacetime, travelling at the speed of light, first postulated by Albert Einstein almost exactly 100 years ago. Nobel prize time.

Time to brush up on your gravitational wave basics, if you haven’t done so! In Gravitational waves and how they distort space, I had a look at what gravitational waves do. Now, on to the next step: How can we measure what they do? How do gravitational wave detectors such as LIGO work?

Recall that this is how a gravitational wave will change the distances between particles, floating freely in a circular formation in empty space:  The wave is moving at right angles to the screen, towards you. I’ve greatly exaggerated the distance changes. For a realistic wave, even the giant distance between the Earth and the Sun would only change by a fraction of the diameter of a hydrogen atom. Tiny changes indeed.

The wave is moving at right angles to the screen, towards you. I’ve greatly exaggerated the distance changes. For a realistic wave, even the giant distance between the Earth and the Sun would only change by a fraction of the diameter of a hydrogen atom. Tiny changes indeed.

How to detect something like this?

The first unsuccessful attempts to detect gravitational waves in the 1960s tried to measure how they make aluminum cylinders ring like a very soft bell. (Tragic story; Joe Weber [1919-2000], the pioneering physicist behind this, was sure he had detected gravitational waves in this way; after thorough analysis and replication attempts, community consensus emerged that he hadn’t.)

Afterwards, physicists came up with alternative scheme. Imagine that you are replacing the black point in the center of the previous animation with a detector, and the rightmost red particle with a laser light source. Now you send light pulses (represented here by fast red dots) from the light source to the detector; let’s first look at this with the gravitational wave switched off:

Every time a light pulse reaches the detector, an indicator light flashes yellow. The pulses are sent out regularly, they all travel at the same speed, hence they also reach the detector in regular intervals.

If a gravitational wave passes through this system, again from the back and coming towards you, distances will change. Let us keep our camera trained on the detector, so the detector remains where it is. The changing distance to the light source, and also the changing distances between the light pulses, and some of the changes in distance between light pulses and detector or source, are due to the gravitational wave. Here is what that would look like (again, hugely exaggerated):

Keep your eye on the blinking light, and you will see that its blinking is not so regular any more. Sometimes, the light blinks faster, sometimes slower. This is an effect of the gravitational wave. An effect by which we can hope to detect the gravitational wave.

“We” in this case are the radio astronomers working on what are known as Pulsar Timing Arrays. The sender of regular pulses are pulsars, rotating neutron stars sweeping a radio beam across our antennas like a cosmic lighthouse. The detectors are radio telescopes here on Earth. Detection is anything but easy. With a single pulsar, you’d need to track pulse arrival times with an accuracy of a few billionths of a second over half a year, and make sure you are not being fooled by various other sources of timing variations. So far, no gravitational waves have been detected in this way, although the radio astronomers are keeping at it.

To see how gravitational wave detectors like LIGO work, we need to make things a little more complex.

Interferometric gravitational wave detectors: the set-up

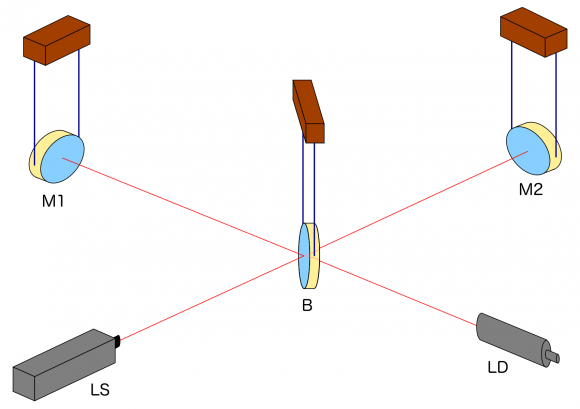

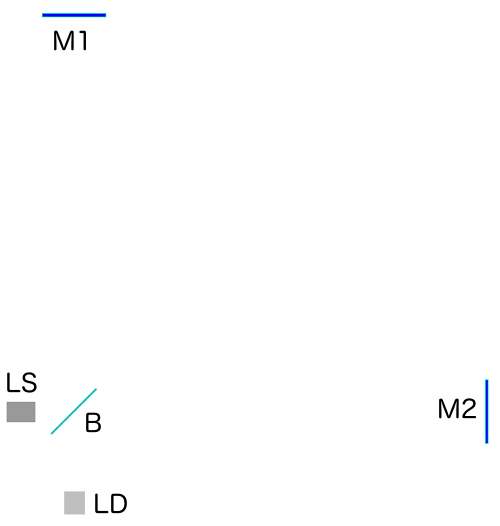

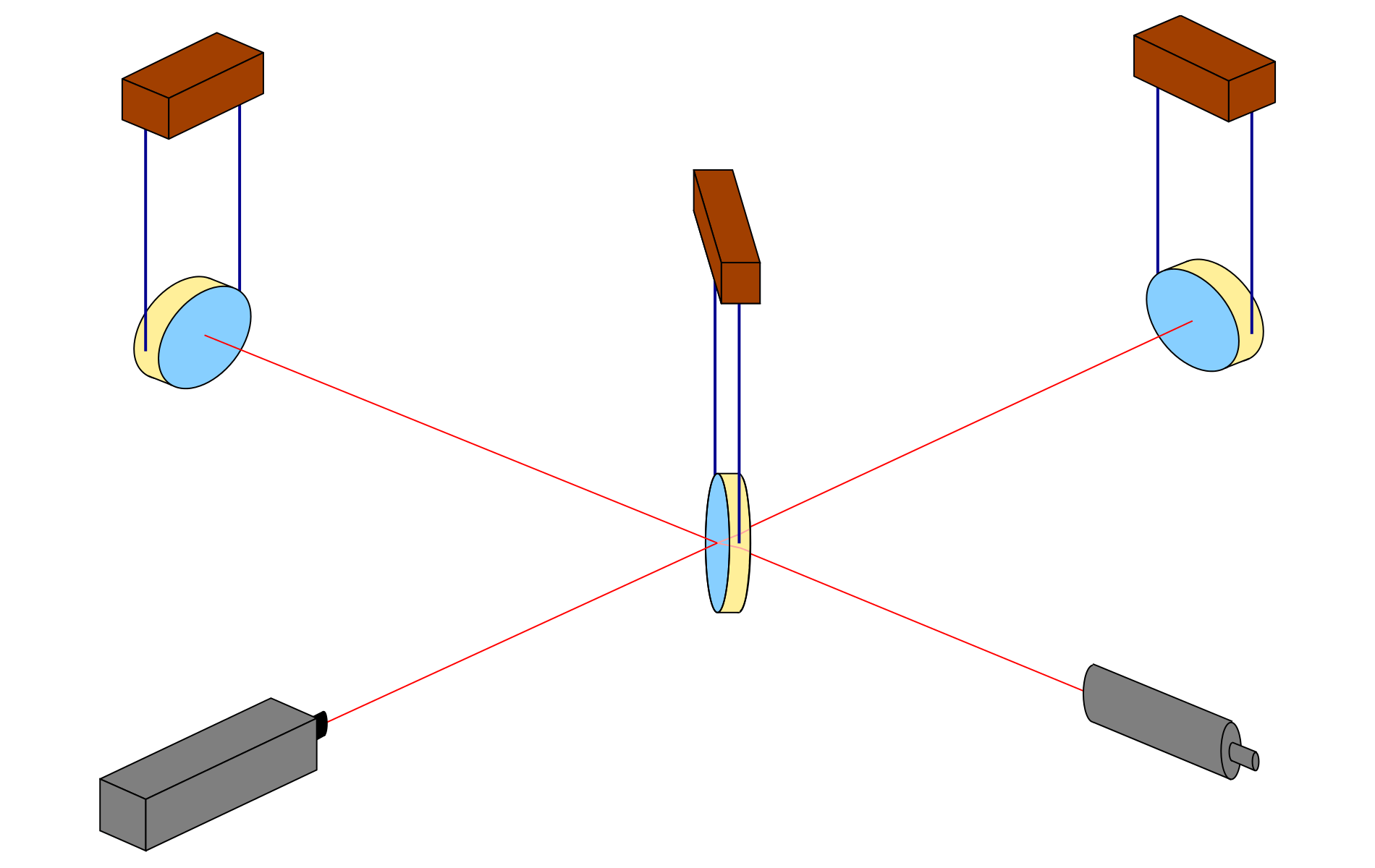

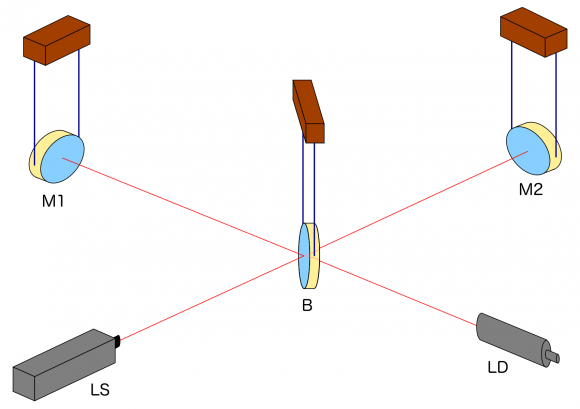

Here is the basic set-up: Two mirrors, a receiver (or “light detector”), a light source and what is known as a beamsplitter:

Light is sent into the detector from the (laser) light source LS to the beamsplitter B which, true to its name, sends half of the light on to the mirror M1 and lets the other half through to the mirror M2. At M1 and M2, respectively, the light is reflected back to the beam splitter. There, the light arriving from M1 (or M2) is split again, with half going towards the light detector LD, the other half back in the direction of the light source LS. We will ignore the latter half and pretend, for the sake of our simplified explanation, that all the light reaching B from M1 or M2 goes on to the light detector LD.

(To avoid confusion, I will always refer to LD as the “light detector” and take the unqualified word “detector” to mean the whole setup.)

This setup, by the way, is called a Michelson Interferometer. We’ll see below why it is a good setup for gravitational wave detectors.

In what follows, we will assume that the mirrors and the beam splitter, shown as being suspended, react to the gravitational wave in the same way freely floating particles would react. The key effects are between the mirrors and the beam splitter in what are called the two arms of the detector. Arm length is huge in today’s detectors, running to a few kilometers. In comparison, light source and light detector are very close to the beamsplitter; changes of the distances between these three do not signify.

Light pulses in a gravitational wave detector

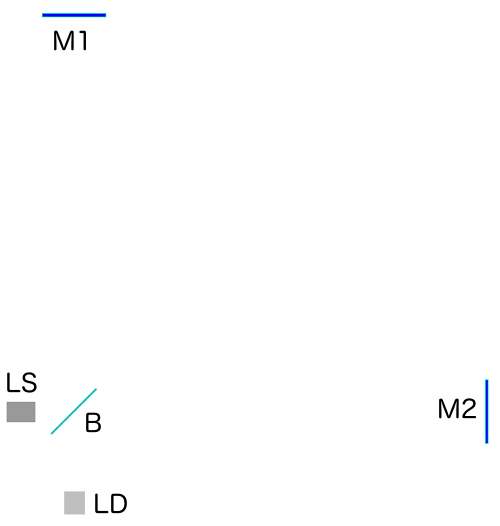

Next, let us see how light pulses run through this detector. Here is the same setup, seen from above:  Light source LS, the two mirrors M1 and M2, the beamsplitter B and the light detector LD: all present and accounted for.

Light source LS, the two mirrors M1 and M2, the beamsplitter B and the light detector LD: all present and accounted for.

Next, we let the light source emit light pulses. For greater clarity, I will make two artificial and unrealistic changes. I will send red and green pulses into the detector, representing the light that goes into the horizontal and the vertical arm, respectively. In reality, there is no distinction, just light apportioned at the beamsplitter. Light running towards M1 will be offset a little to the left, light coming back from M1 to the right, for better clarity. Same goes for M2. This, too, is different in a real detector. That said, here come the light pulses:  Light starts at the light source to the left. Light that has left the source together, travels together (so green and red pulses are side by side) until the beam splitter. The beam splitter then sends the green pulses on their upward journey and lets the red pulses pass on their way towards the mirror on the right. All the particles that arrive back at the beamsplitter after reflection at M1 or M2. At the beamsplitter, they are directed towards the light detector at the bottom.

Light starts at the light source to the left. Light that has left the source together, travels together (so green and red pulses are side by side) until the beam splitter. The beam splitter then sends the green pulses on their upward journey and lets the red pulses pass on their way towards the mirror on the right. All the particles that arrive back at the beamsplitter after reflection at M1 or M2. At the beamsplitter, they are directed towards the light detector at the bottom.

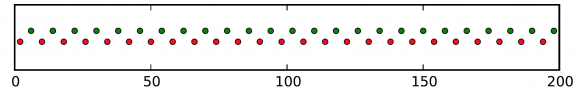

In this setup, the horizontal arm is slightly longer than the vertical arm. Red particles have to cover some extra distance. That is why they arrive at the detector a bit later, and we get an alternating rhythm: green, red, green, red, with equal distances in between. This will become important later on.

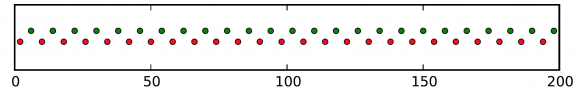

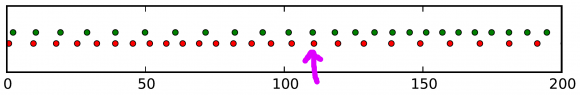

Here is a diagram, a kind of registration strip, which shows the arrival times for red and green pulses at the light detector (time is measured in “animation frames”):  The pattern is clear: red and green pulses arrive evenly spaced, one after the other.

The pattern is clear: red and green pulses arrive evenly spaced, one after the other.

Bring on the gravitational wave!

Next, let’s switch on our standard gravitational wave (exaggerated, passing through the screen towards you, and so on). Here is the result:  We have trained our camera on the beamsplitter (so in our image, the beamsplitter doesn’t move). We ignore any slight changes in distance between beamsplitter and light source/light detector. Instead, we focus on the mirrors M1 and M2, which change their distance from the beamsplitter just as we would expect from the earlier animations.

We have trained our camera on the beamsplitter (so in our image, the beamsplitter doesn’t move). We ignore any slight changes in distance between beamsplitter and light source/light detector. Instead, we focus on the mirrors M1 and M2, which change their distance from the beamsplitter just as we would expect from the earlier animations.

Look at the way the pulses arrive at our light detector: sometimes red and green are almost evenly spaced, sometimes they close together. That is caused by the gravitational wave. Without the wave, we had strict regularity.

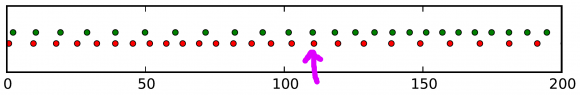

Here is the corresponding “registration strip” diagram. You can see that at some times, the light pulses of each color are closer together, at others, farther apart:

At the time I have marked with a hand-drawn arrow, red and green pulses arrive almost in unison!

The pattern is markedly different from the scenario without a gravitational wave. Detect this change in the pattern, and you have detected the gravitational wave.

Running interference

If you’ve wondered why detectors like LIGO are called interferometric gravitational wave detectors, we will need to think about waves a bit more. If not, let me just state that detectors like LIGO use the wave properties of light to measure the changes in pulse arrival rate you have seen in the last animation. To skip the details, feel free to jump ahead to the last section, “…and now for something a thousand times more complicated.”

Light is a wave, with crests and troughs corresponding to maxima and minima of the electric and of the magnetic field. While the animations I have shown you track the propagation of light pulses, they can also be used to understand what happens to a light wave in the interferometer. Just assume that each of the moving red and green dots in the detector marks the position of a wave crest.

Particles just add up. Take 2 particle and add 2 particles, and you will end up with 4 particles. But if you add up (combine, superimpose) waves, it depends. Sometimes, one wave plus another wave is indeed a bigger wave. Sometimes, it’s a smaller wave, or no wave at all. And sometimes it’s complicated.

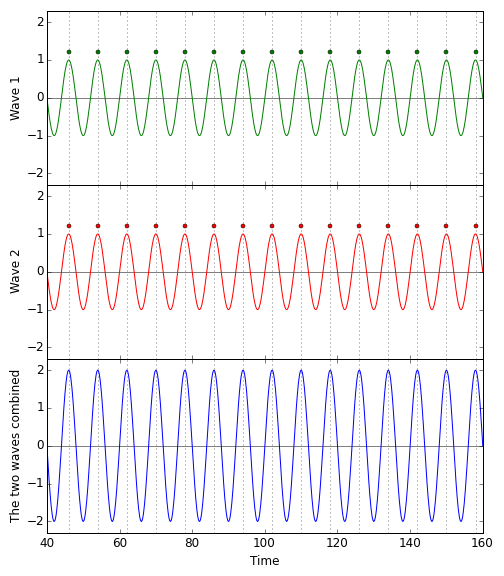

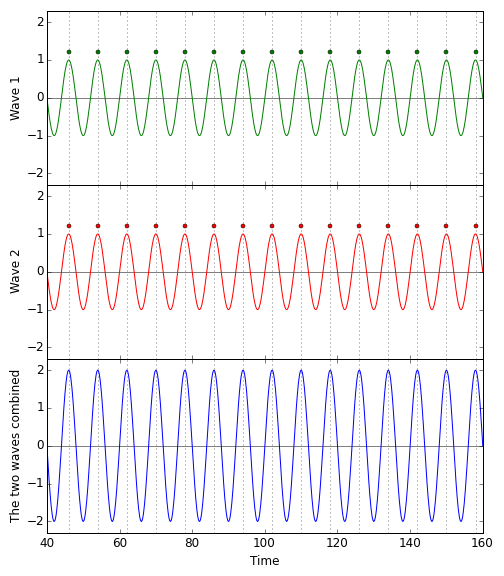

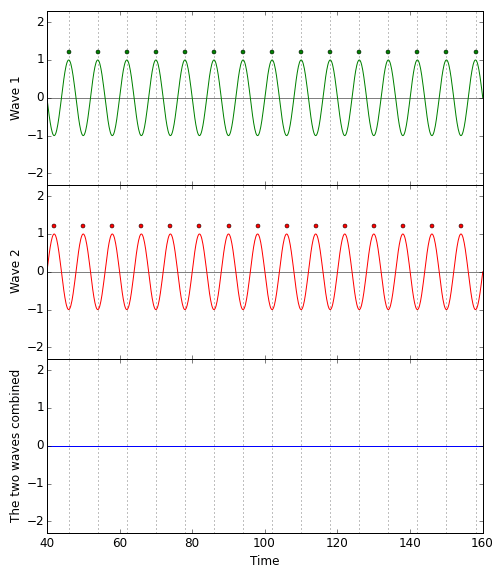

When two waves are in perfect sync, the crests of the one aligning with the crests of the other, and the troughs aligning, too, you indeed get a bigger wave. The following diagram shows at which times the different parts of two light waves arrive at the light detector, and how they add up. (I’ve placed a dot on top of each crest; that is what the dots where meant to signify, after all.)  On top, the green wave, perfectly aligned with the red wave (which, for clarity, is shown directly below the green wave). Add the two waves up, and you will get the (markedly stronger) blue wave in the bottom panel.

On top, the green wave, perfectly aligned with the red wave (which, for clarity, is shown directly below the green wave). Add the two waves up, and you will get the (markedly stronger) blue wave in the bottom panel.

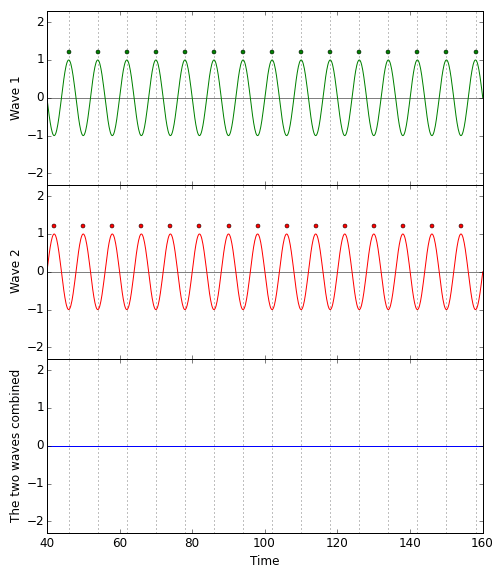

Not so if the two waves are maximally misaligned, the crests of each aligned with the troughs of the other. A crest and a trough cancel each other out. The sum of a wave and a maximally misaligned wave of equal strength is: no wave at all. Here is the corresponding diagram:  Recall that this was exactly the setup for our gravitational wave detector in the absence of gravitational waves: Red and green pulses with equal spacing; troughs of the one wave perfectly aligned with the crests of the other. The result: No light at the light detector. (For realistic gravitational wave detectors, that is almost true.)

Recall that this was exactly the setup for our gravitational wave detector in the absence of gravitational waves: Red and green pulses with equal spacing; troughs of the one wave perfectly aligned with the crests of the other. The result: No light at the light detector. (For realistic gravitational wave detectors, that is almost true.)

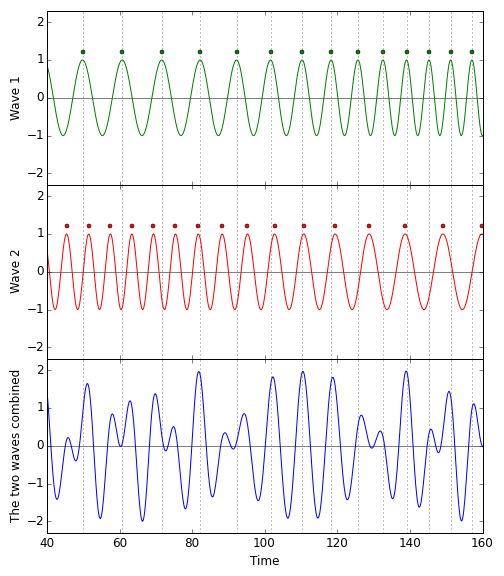

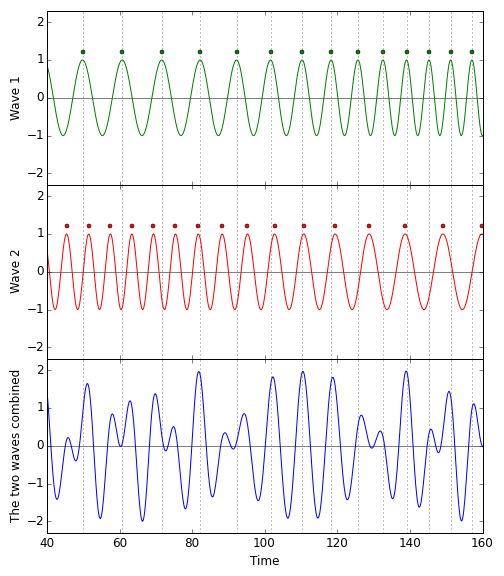

When a gravitational wave passes through the detector, the situation changes. Here is the corresponding pattern of pulse/wave crest arrival times for the animation above:  The blue pattern, which is the sum of the red and the green, is complex. But it is not a flat line. There is light at the light detector where there was no light before, and the cause of the change is the gravitational wave passing through.

The blue pattern, which is the sum of the red and the green, is complex. But it is not a flat line. There is light at the light detector where there was no light before, and the cause of the change is the gravitational wave passing through.

All in all, this makes a (highly simplified) version of how gravitational wave detectors such as LIGO work. Whatever the scientists will report this Thursday, it is based on light signals at the exit of such an interferometric detector.

And now for something a thousand times more complicated

Real gravitational wave detectors are, of course, much more complicated than that. I haven’t even started talking about the many disturbances scientists need to take into account – and to suppress as far as possible. How do you suspend the mirrors so that (at least for certain gravitational waves) they will indeed be influenced as if they were freely floating particles? How do you prevent seismic noise, cars or trains in the wider neighborhood and so on from moving your mirrors a tiny little bit (either by vibrations or by their own gravity)? What about fluctuations of the laser light?

Gravitational wave hunting is largely a hunt for noise, and for ways of suppressing that noise. The LIGO gravitational wave detectors and their kin are highly complex machines, with hundreds of control circuits, highly elaborate mirror suspensions, the most stable lasers known to physics (and some of the most high-powered). The technology has been contributed by numerous group from all over the world.

But all this is taking us too far, and I refer you to the pages of the detectors and collaborations for additional information:

LIGO pages at Caltech

Pages of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration

GEO 600 pages

VIRGO / EGO pages

You can find some further information about gravitational waves on the Einstein Online website:

Einstein Online: Spotlights on gravitational waves

Update: Gravitational Waves Discovered

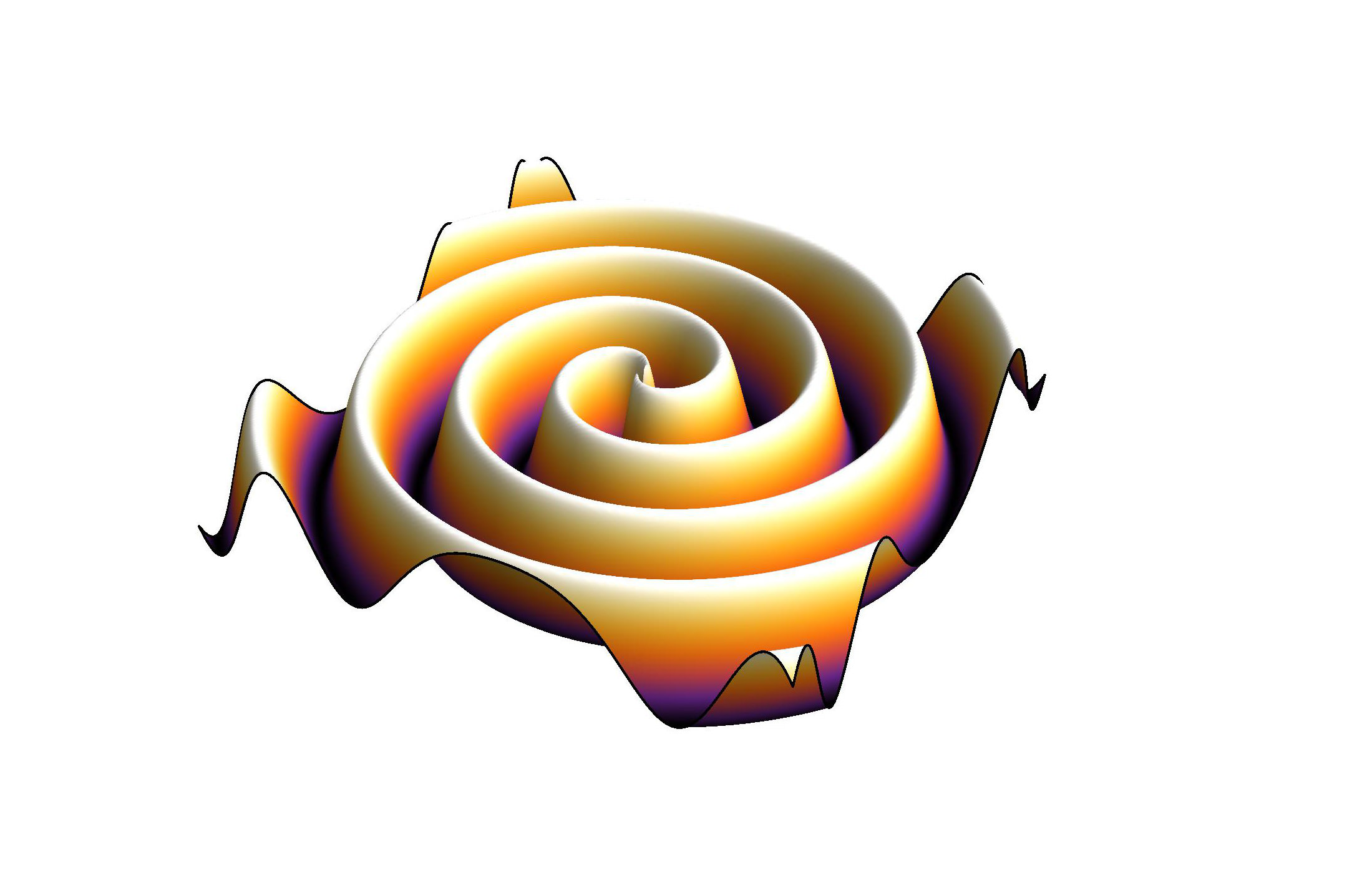

This is not something you would see, of course. The wave that is pictured here represents the strength of the minute changes in distance that would be caused by the gravitational wave, just as we’ve seen in

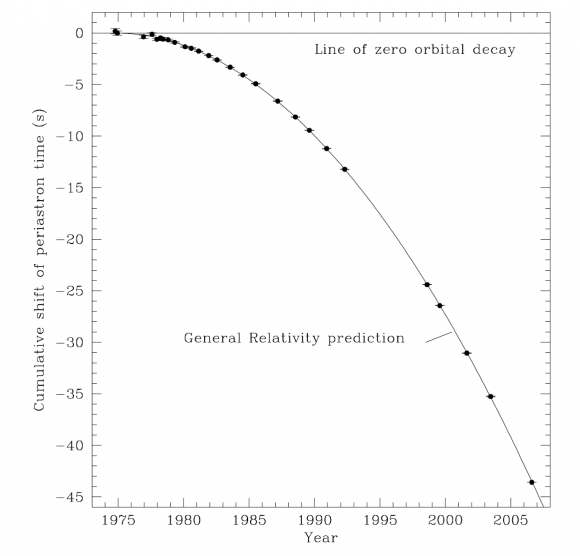

This is not something you would see, of course. The wave that is pictured here represents the strength of the minute changes in distance that would be caused by the gravitational wave, just as we’ve seen in  As the two neutron stars speed up, they will reach the point of closest approach within their orbit earlier and earlier. How much earlier, in seconds, is plotted on the vertical axis, year of measurement on the horizontal axis.

As the two neutron stars speed up, they will reach the point of closest approach within their orbit earlier and earlier. How much earlier, in seconds, is plotted on the vertical axis, year of measurement on the horizontal axis. You can see how the frequency and intensity increase right up to time 0, when the two neutron stars collide and merge.

You can see how the frequency and intensity increase right up to time 0, when the two neutron stars collide and merge.

The wave is moving at right angles to the screen, towards you. I’ve greatly exaggerated the distance changes. For a realistic wave, even the giant distance between the Earth and the Sun would only change by a fraction of the diameter of a hydrogen atom. Tiny changes indeed.

The wave is moving at right angles to the screen, towards you. I’ve greatly exaggerated the distance changes. For a realistic wave, even the giant distance between the Earth and the Sun would only change by a fraction of the diameter of a hydrogen atom. Tiny changes indeed.

Light source LS, the two mirrors M1 and M2, the beamsplitter B and the light detector LD: all present and accounted for.

Light source LS, the two mirrors M1 and M2, the beamsplitter B and the light detector LD: all present and accounted for. Light starts at the light source to the left. Light that has left the source together, travels together (so green and red pulses are side by side) until the beam splitter. The beam splitter then sends the green pulses on their upward journey and lets the red pulses pass on their way towards the mirror on the right. All the particles that arrive back at the beamsplitter after reflection at M1 or M2. At the beamsplitter, they are directed towards the light detector at the bottom.

Light starts at the light source to the left. Light that has left the source together, travels together (so green and red pulses are side by side) until the beam splitter. The beam splitter then sends the green pulses on their upward journey and lets the red pulses pass on their way towards the mirror on the right. All the particles that arrive back at the beamsplitter after reflection at M1 or M2. At the beamsplitter, they are directed towards the light detector at the bottom. The pattern is clear: red and green pulses arrive evenly spaced, one after the other.

The pattern is clear: red and green pulses arrive evenly spaced, one after the other. We have trained our camera on the beamsplitter (so in our image, the beamsplitter doesn’t move). We ignore any slight changes in distance between beamsplitter and light source/light detector. Instead, we focus on the mirrors M1 and M2, which change their distance from the beamsplitter just as we would expect from the earlier animations.

We have trained our camera on the beamsplitter (so in our image, the beamsplitter doesn’t move). We ignore any slight changes in distance between beamsplitter and light source/light detector. Instead, we focus on the mirrors M1 and M2, which change their distance from the beamsplitter just as we would expect from the earlier animations.

On top, the green wave, perfectly aligned with the red wave (which, for clarity, is shown directly below the green wave). Add the two waves up, and you will get the (markedly stronger) blue wave in the bottom panel.

On top, the green wave, perfectly aligned with the red wave (which, for clarity, is shown directly below the green wave). Add the two waves up, and you will get the (markedly stronger) blue wave in the bottom panel. Recall that this was exactly the setup for our gravitational wave detector in the absence of gravitational waves: Red and green pulses with equal spacing; troughs of the one wave perfectly aligned with the crests of the other. The result: No light at the light detector. (For realistic gravitational wave detectors, that is almost true.)

Recall that this was exactly the setup for our gravitational wave detector in the absence of gravitational waves: Red and green pulses with equal spacing; troughs of the one wave perfectly aligned with the crests of the other. The result: No light at the light detector. (For realistic gravitational wave detectors, that is almost true.) The blue pattern, which is the sum of the red and the green, is complex. But it is not a flat line. There is light at the light detector where there was no light before, and the cause of the change is the gravitational wave passing through.

The blue pattern, which is the sum of the red and the green, is complex. But it is not a flat line. There is light at the light detector where there was no light before, and the cause of the change is the gravitational wave passing through.