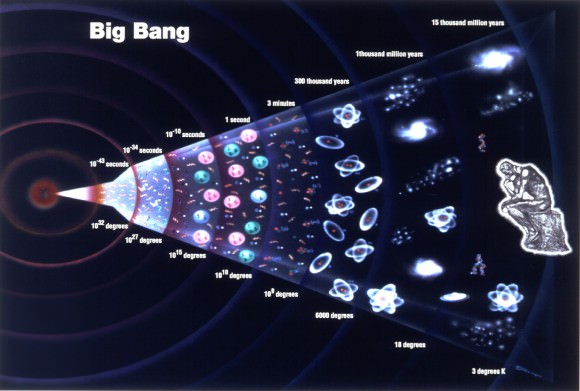

Ever since scientists first discovered the existence of black holes in our universe, we have all wondered: what could possibly exist beyond the veil of that terrible void? In addition, ever since the theory of General Relativity was first proposed, scientists have been forced to wonder, what could have existed before the birth of the Universe – i.e. before the Big Bang?

Interestingly enough, these two questions have come to be resolved (after a fashion) with the theoretical existence of something known as a Gravitational Singularity – a point in space-time where the laws of physics as we know them break down. And while there remain challenges and unresolved issues about this theory, many scientists believe that beneath veil of an event horizon, and at the beginning of the Universe, this was what existed.

Definition:

In scientific terms, a gravitational singularity (or space-time singularity) is a location where the quantities that are used to measure the gravitational field become infinite in a way that does not depend on the coordinate system. In other words, it is a point in which all physical laws are indistinguishable from one another, where space and time are no longer interrelated realities, but merge indistinguishably and cease to have any independent meaning.

Origin of Theory:

Singularities were first predicated as a result of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, which resulted in the theoretical existence of black holes. In essence, the theory predicted that any star reaching beyond a certain point in its mass (aka. the Schwarzschild Radius) would exert a gravitational force so intense that it would collapse.

At this point, nothing would be capable of escaping its surface, including light. This is due to the fact the gravitational force would exceed the speed of light in vacuum – 299,792,458 meters per second (1,079,252,848.8 km/h; 670,616,629 mph).

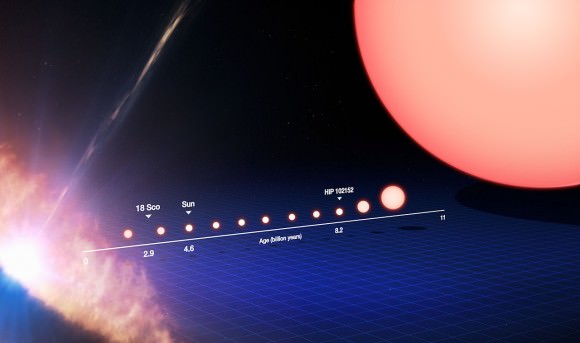

This phenomena is known as the Chandrasekhar Limit, named after the Indian astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, who proposed it in 1930. At present, the accepted value of this limit is believed to be 1.39 Solar Masses (i.e. 1.39 times the mass of our Sun), which works out to a whopping 2.765 x 1030 kg (or 2,765 trillion trillion metric tons).

Another aspect of modern General Relativity is that at the time of the Big Bang (i.e. the initial state of the Universe) was a singularity. Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking both developed theories that attempted to answer how gravitation could produce singularities, which eventually merged together to be known as the Penrose–Hawking Singularity Theorems.

According to the Penrose Singularity Theorem, which he proposed in 1965, a time-like singularity will occur within a black hole whenever matter reaches certain energy conditions. At this point, the curvature of space-time within the black hole becomes infinite, thus turning it into a trapped surface where time ceases to function.

The Hawking Singularity Theorem added to this by stating that a space-like singularity can occur when matter is forcibly compressed to a point, causing the rules that govern matter to break down. Hawking traced this back in time to the Big Bang, which he claimed was a point of infinite density. However, Hawking later revised this to claim that general relativity breaks down at times prior to the Big Bang, and hence no singularity could be predicted by it.

Some more recent proposals also suggest that the Universe did not begin as a singularity. These includes theories like Loop Quantum Gravity, which attempts to unify the laws of quantum physics with gravity. This theory states that, due to quantum gravity effects, there is a minimum distance beyond which gravity no longer continues to increase, or that interpenetrating particle waves mask gravitational effects that would be felt at a distance.

Types of Singularities:

The two most important types of space-time singularities are known as Curvature Singularities and Conical Singularities. Singularities can also be divided according to whether they are covered by an event horizon or not. In the case of the former, you have the Curvature and Conical; whereas in the latter, you have what are known as Naked Singularities.

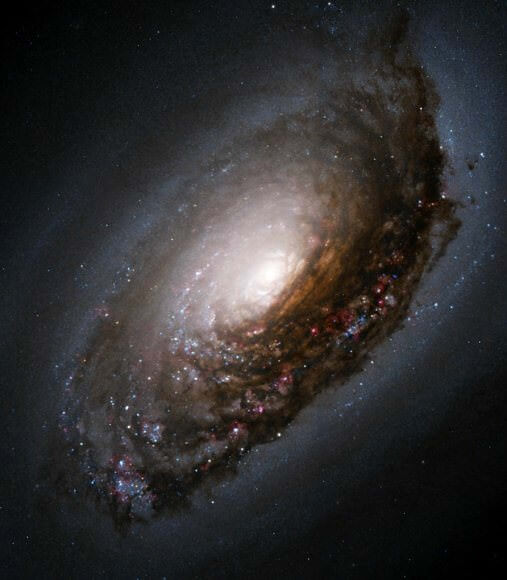

A Curvature Singularity is best exemplified by a black hole. At the center of a black hole, space-time becomes a one-dimensional point which contains a huge mass. As a result, gravity become infinite and space-time curves infinitely, and the laws of physics as we know them cease to function.

Conical singularities occur when there is a point where the limit of every general covariance quantity is finite. In this case, space-time looks like a cone around this point, where the singularity is located at the tip of the cone. An example of such a conical singularity is a cosmic string, a type of hypothetical one-dimensional point that is believed to have formed during the early Universe.

And, as mentioned, there is the Naked Singularity, a type of singularity which is not hidden behind an event horizon. These were first discovered in 1991 by Shapiro and Teukolsky using computer simulations of a rotating plane of dust that indicated that General Relativity might allow for “naked” singularities.

In this case, what actually transpires within a black hole (i.e. its singularity) would be visible. Such a singularity would theoretically be what existed prior to the Big Bang. The key word here is theoretical, as it remains a mystery what these objects would look like.

For the moment, singularities and what actually lies beneath the veil of a black hole remains a mystery. As time goes on, it is hoped that astronomers will be able to study black holes in greater detail. It is also hoped that in the coming decades, scientists will find a way to merge the principles of quantum mechanics with gravity, and that this will shed further light on how this mysterious force operates.

We have many interesting articles about gravitational singularities here at Universe Today. Here is 10 Interesting Facts About Black Holes, What Would A Black Hole Look Like?, Was the Big Bang Just a Black Hole?, Goodbye Big Bang, Hello Black Hole?, Who is Stephen Hawking?, and What’s on the Other Side of a Black Hole?

If you’d like more info on singularity, check out these articles from NASA and Physlink.

Astronomy Cast has some relevant episodes on the subject. Here’s Episode 6: More Evidence for the Big Bang, and Episode 18: Black Holes Big and Small and Episode 21: Black Hole Questions Answered.

Sources: