Could a new, fifth force of nature provide some answers to our biggest questions about dark matter and dark energy? We’re working on it.

Continue reading “Is There a Fifth Force of Nature?”Can an Asteroid's Movements Reveal a New Force in the Universe?

There are four fundamental forces in the Universe. These forces govern all the ways matter can interact, from the sound of an infant’s laugh to the clustering of galaxies a billion light-years away. At least that’s what we’ve thought until recently. Things such as dark matter and dark energy, as well as a few odd interactions in particle physics, have led some researchers to propose a fifth fundamental force. Depending on the model you consider, this new force could explain dark matter and cosmic expansion, or it could interact with elemental particles we haven’t yet detected. There are lots of theories about this hypothetical force. What there isn’t a lot of is evidence. So a new study is looking for evidence in the orbits of asteroids.

Continue reading “Can an Asteroid's Movements Reveal a New Force in the Universe?”Physicists Maybe, Just Maybe, Confirm the Possible Discovery of 5th Force of Nature

For some time, physicists have understood that all known phenomena in the Universe are governed by four fundamental forces. These include weak nuclear force, strong nuclear force, electromagnetism and gravity. Whereas the first three forces of are all part of the Standard Model of particle physics, and can be explained through quantum mechanics, our understanding of gravity is dependent upon Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.

Understanding how these four forces fit together has been the aim of theoretical physics for decades, which in turn has led to the development of multiple theories that attempt to reconcile them (i.e. Super String Theory, Quantum Gravity, Grand Unified Theory, etc). However, their efforts may be complicated (or helped) thanks to new research that suggests there might just be a fifth force at work.

In a paper that was recently published in the journal Physical Review Letters, a research team from the University of California, Irvine explain how recent particle physics experiments may have yielded evidence of a new type of boson. This boson apparently does not behave as other bosons do, and may be an indication that there is yet another force of nature out there governing fundamental interactions.

As Jonathan Feng, a professor of physics & astronomy at UCI and one of the lead authors on the paper, said:

“If true, it’s revolutionary. For decades, we’ve known of four fundamental forces: gravitation, electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces. If confirmed by further experiments, this discovery of a possible fifth force would completely change our understanding of the universe, with consequences for the unification of forces and dark matter.”

The efforts that led to this potential discovery began back in 2015, when the UCI team came across a study from a group of experimental nuclear physicists from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Institute for Nuclear Research. At the time, these physicists were looking into a radioactive decay anomaly that hinted at the existence of a light particle that was 30 times heavier than an electron.

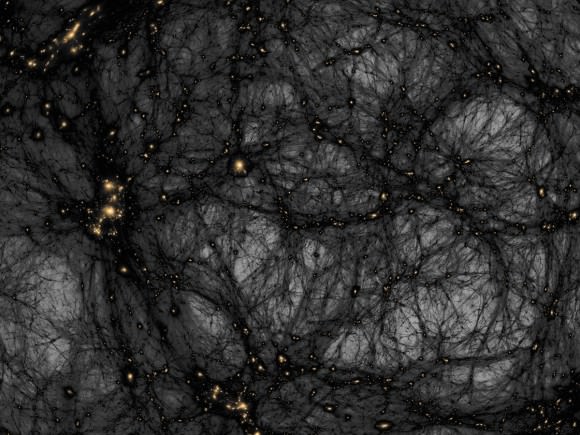

In a paper describing their research, lead researcher Attila Krasznahorka and his colleagues claimed that what they were observing might be the creation of “dark photons”. In short, they believed that they might have at last found evidence of Dark Matter, the mysterious, invisible mass that makes up about 85% of the Universe’s mass.

This report was largely overlooked at the time, but gained widespread attention earlier this year when Prof. Feng and his research team found it and began assessing its conclusions. But after studying the Hungarian teams results and comparing them to previous experiments, they concluded that the experimental evidence did not support the existence of dark photons.

Instead, they proposed that the discovery could indicate the possible presence of a fifth fundamental force of nature. These findings were published in arXiv in April, which was followed-up by a paper titled “Particle Physics Models for the 17 MeV Anomaly in Beryllium Nuclear Decays“, which was published in PRL this past Friday.

Essentially, the UCI team argue that instead of a dark photon, what the Hungarian research team might have witnessed was the creation of a previously undiscovered boson – which they have named the “protophobic X boson”. Whereas other bosons interact with electrons and protons, this hypothetical boson interacts with only electrons and neutrons, and only at an extremely limited range.

This limited interaction is believed to be the reason why the particle has remained unknown until now, and why the adjectives “photobic” and “X” are added to the name. “There’s no other boson that we’ve observed that has this same characteristic,” said Timothy Tait, a professor of physics & astronomy at UCI and the co-author of the paper. “Sometimes we also just call it the ‘X boson,’ where ‘X’ means unknown.”

If such a particle does exist, the possibilities for research breakthroughs could be endless. Feng hopes it could be joined with the three other forces governing particle interactions (electromagnetic, strong and weak nuclear forces) as a larger, more fundamental force. Feng also speculated that this possible discovery could point to the existence of a “dark sector” of our universe, which is governed by its own matter and forces.

“It’s possible that these two sectors talk to each other and interact with one another through somewhat veiled but fundamental interactions,” he said. “This dark sector force may manifest itself as this protophopic force we’re seeing as a result of the Hungarian experiment. In a broader sense, it fits in with our original research to understand the nature of dark matter.”

If this should prove to be the case, then physicists may be closer to figuring out the existence of dark matter (and maybe even dark energy), two of the greatest mysteries in modern astrophysics. What’s more, it could aid researchers in the search for physics beyond the Standard Model – something the researchers at CERN have been preoccupied with since the discovery of the Higgs Boson in 2012.

But as Feng notes, we need to confirm the existence of this particle through further experiments before we get all excited by its implications:

“The particle is not very heavy, and laboratories have had the energies required to make it since the ’50s and ’60s. But the reason it’s been hard to find is that its interactions are very feeble. That said, because the new particle is so light, there are many experimental groups working in small labs around the world that can follow up the initial claims, now that they know where to look.”

As the recent case involving CERN – where LHC teams were forced to announce that they had not discovered two new particles – demonstrates, it is important not to count our chickens before they are roosted. As always, cautious optimism is the best approach to potential new findings.

Further Reading: University of California, Irvine