Time travel is a staple of science fiction, and not without reason. Who wouldn’t want to go back in time to explore history, or save the world from catastrophe. Time travel has also been deeply studied within the context of theoretical physics because it tests the limits of our scientific theories. If time travel is possible, it has implications for everything from the origin of the universe to the existence of free will. One of the central problems of time travel theory is that it gives rise to logical paradoxes. But a couple of researchers think they have solved the pesky paradox problem.

Continue reading “Time Travel, Without the Pesky Paradoxes”Does Free Will Exist? Ancient Quasars May Hold the Clue.

Do you believe in free will? Are people able to decide their own destinies, whether it’s on what continent they’ll live, who or if they’ll marry, or just where they’ll get lunch today? Or are we just the unwitting pawns of some greater cosmic mechanism at work, ticking away the seconds and steering everyone and everything toward an inevitable, predetermined fate?

Philosophical debates aside, MIT researchers are actually looking to move past this age-old argument in their experiments once and for all, using some of the most distant and brilliant objects in the Universe.

Rather than ponder the ancient musings of Plato and Aristotle, researchers at MIT were trying to determine how to get past a more recent conundrum in physics: Bell’s Theorem. Proposed by Irish physicist John Bell in 1964, the principle attempts to come to terms with the behavior of “entangled” quantum particles separated by great distances but somehow affected simultaneously and instantaneously by the measurement of one or the other — previously referred to by Einstein as “spooky action at a distance.”

The problem with such spookiness in the quantum universe is that it seems to violate some very basic tenets of what we know about the macroscopic universe, such as information traveling faster than light. (A big no-no in physics.)

(Note: actual information is not transferred via quantum entanglement, but rather it’s the transfer of state between particles that can occur at thousands of times the speed of light.)

Read more: Spooky Experiment on ISS Could Pioneer New Quantum Communications Network

Then again, testing against Bell’s Theorem has resulted in its own weirdness (even as quantum research goes.) While some of the intrinsic “loopholes” in Bell’s Theorem have been sealed up, one odd suggestion remains on the table: what if a quantum-induced absence of free will (i.e., hidden variables) is conspiring to affect how researchers calibrate their detectors and collect data, somehow steering them toward a conclusion biased against classical physics?

“It sounds creepy, but people realized that’s a logical possibility that hasn’t been closed yet,” said David Kaiser, Germeshausen Professor of the History of Science and senior lecturer in the Department of Physics at MIT in Cambridge, Mass. “Before we make the leap to say the equations of quantum theory tell us the world is inescapably crazy and bizarre, have we closed every conceivable logical loophole, even if they may not seem plausible in the world we know today?”

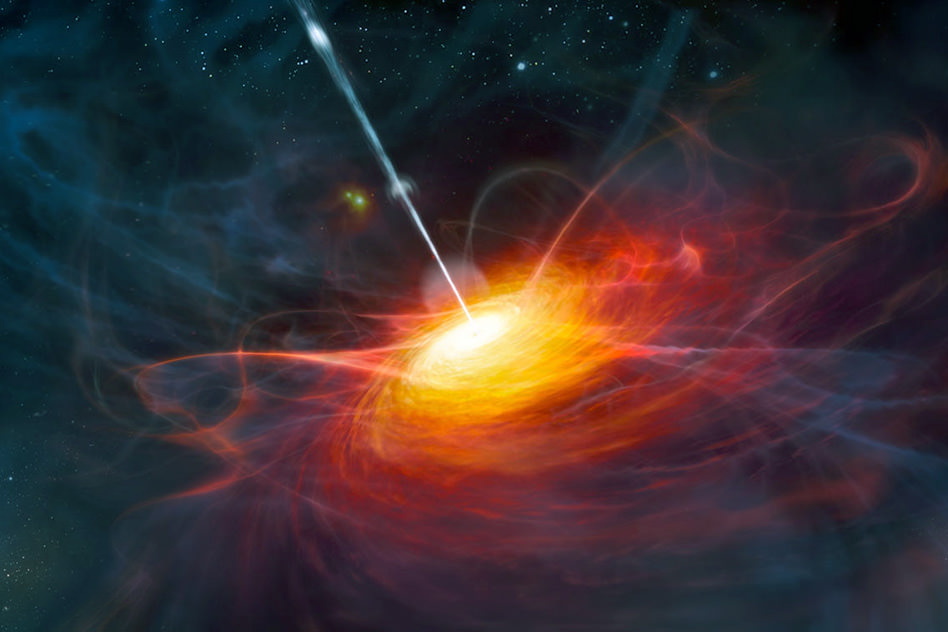

So in order to clear the air of any possible predestination by entangled interlopers, Kaiser and MIT postdoc Andrew Friedman, along with Jason Gallicchio of the University of Chicago, propose to look into the distant, early Universe for sufficiently unprejudiced parties: ancient quasars that have never, ever been in contact.

According to a news release from MIT:

…an experiment would go something like this: A laboratory setup would consist of a particle generator, such as a radioactive atom that spits out pairs of entangled particles. One detector measures a property of particle A, while another detector does the same for particle B. A split second after the particles are generated, but just before the detectors are set, scientists would use telescopic observations of distant quasars to determine which properties each detector will measure of a respective particle. In other words, quasar A determines the settings to detect particle A, and quasar B sets the detector for particle B.

By using the light from objects that came into existence just shortly after the Big Bang to calibrate their detectors, the team hopes to remove any possibility of entanglement… and determine what’s really in charge of the Universe.

“I think it’s fair to say this is the final frontier, logically speaking, that stands between this enormously impressive accumulated experimental evidence and the interpretation of that evidence saying the world is governed by quantum mechanics,” said Kaiser.

Then again, perhaps that’s exactly what they’re supposed to do…

The paper was published this week in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Source: MIT Media Relations

Want to read more about the admittedly complex subject of entanglement and hidden variables (which may or may not really have anything to do with where you eat lunch?) Click here.