Children often ask simple questions that make you wonder if you really understand your subject. An young acquaintance of mine named Collin wondered why the colors of the rainbow were always in the same order — red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. Why don’t they get mixed up?

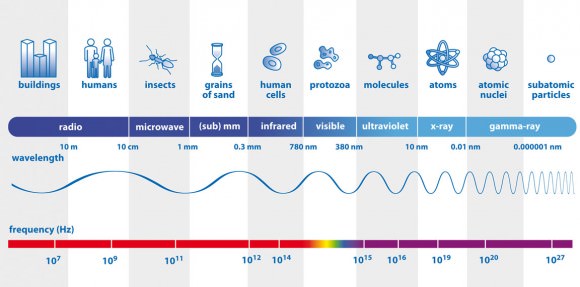

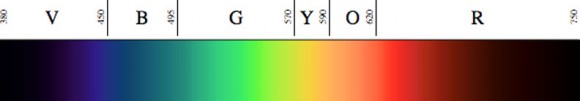

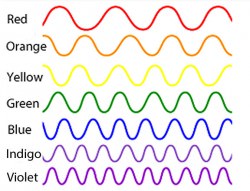

The familiar sequence is captured in the famous Roy G. Biv acronym, which describes the sequence of rainbow colors beginning with red, which has the longest wavelength, and ending in violet, the shortest. Wavelength — the distance between two successive wave crests — and frequency, the number of waves of light that pass a given point every second, determine the color of light.

The cone cells in our retinas respond to wavelengths of light between 650 nanometers (red) to 400 (violet). A nanometer is equal to one-billionth of a meter. Considering that a human hair is 80,000-100,000 nanometers wide, visible light waves are tiny things indeed.

So why Roy G. Biv and not Rob G. Ivy? When light passes through a vacuum it does so in a straight line without deviation at its top speed of 186,000 miles a second (300,000 km/sec). At this speed, the fastest known in the universe as described in Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity, light traveling from the computer screen to your eyes takes only about 1/1,000,000,000 of second. Damn fast.

But when we look beyond the screen to the big, wide universe, light seems to slow to a crawl, taking all of 4.4 hours just to reach Pluto and 25,000 years to fly by the black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy. Isn’t there something faster? Einstein would answer with an emphatic “No!”

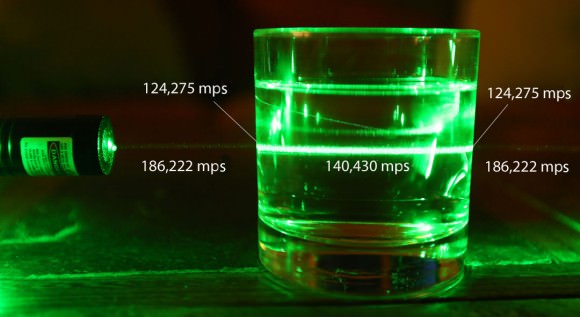

One of light’s most interesting properties is that it changes speed depending on the medium through which it travels. While a beam’s velocity through the air is nearly the same as in a vacuum, “thicker” mediums slow it down considerably. One of the most familiar is water. When light crosses from air into water, say a raindrop, its speed drops to 140,430 miles a second (226,000 km/sec). Glass retards light rays to 124,275 miles/second, while the carbon atoms that make up diamond crunch its speed down to just 77,670 miles/second.

Why light slows down is a bit complicated but so interesting, let’s take a moment to describe the process. Light entering water immediately gets absorbed by atoms of oxygen and hydrogen, causing their electrons to vibrate momentarily before it’s re-emitting as light. Free again, the beam now travels on until it slams into more atoms, gets their electrons vibrating and gets reemitted again. And again. And again.

Like an assembly line, the cycle of absorption and reemission continues until the ray exits the drop. Even though every photon (or wave – your choice) of light travels at the vacuum speed of light in the voids between atoms, the minute time delays during the absorption and reemission process add up to cause the net speed of the light beam to slow down. When it finally leaves the drop, it resumes its normal speed through the airy air.

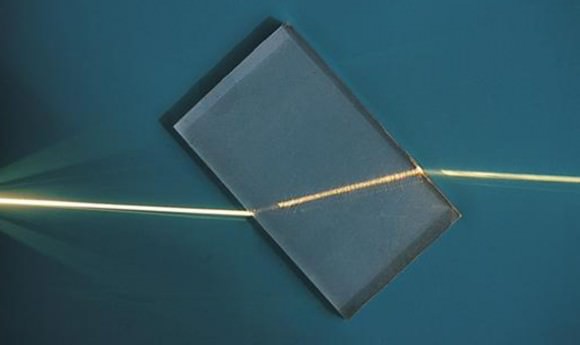

Let’s return now to rainbows. When light passes from one medium to another and its speed drops, it also gets bent or refracted. Plop a pencil in a glass half filled with water and and you’ll see what I mean.

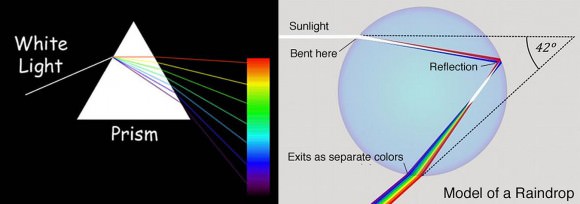

Up to this point, we’ve been talking about white light only, but as we all learned in elementary science, Sir Isaac Newton conducted experiments with prisms in the late 1600s and discovered that white light is comprised of all the colors of the rainbow. It’s no surprise that each of those colors travels at a slightly different speed through a water droplet. Red light interacts only weakly with the electrons of the atoms and is refracted and slowed the least. Shorter wavelength violet light interacts more strongly with the electrons and suffers a greater degree of refraction and slowdown.

Rainbows form when billions of water droplets act like miniature prisms and refract sunlight. Violet (the most refracted) shows up at the bottom or inner edge of the arc. Orange and yellow are refracted a bit less than violet and take up the middle of the rainbow. Red light, least affected by refraction, appears along the arc’s outer edge.

Because their speeds through water (and other media) are a set property of light, and since speed determines how much each is bent as they cross from air to water, they always fall in line as Roy G. Biv. Or the reverse order if the light beam reflects twice inside the raindrop before exiting, but the relation of color to color is always preserved. Nature doesn’t and can’t randomly mix up the scheme. As Scotty from Star Trek would say: “You can’t change the laws of physics!”

So to answer Collin’s original question, the colors of light always stay in the same order because each travels at a different speed when refracted at an angle through a raindrop or prism.

Not only does light change its speed when it enters a new medium, its wavelength changes, but its frequency remains the same. While wavelength may be a useful way to describe the colors of light in a single medium (air, for instance), it doesn’t work when light transitions from one medium to another. For that we rely on its frequency or how many waves of colored light pass a set point per second.

Higher frequency violet light crams in 790 trillion waves per second (cycles per second) vs. 390 trillion for red. Interestingly, the higher the frequency, the more energy a particular flavor of light carries, one reason why UV will give you a sunburn and red light won’t.

When a ray of sunlight enters a raindrop, the distance between each successive crest of the light wave decreases, shortening the beam’s wavelength. That might make you think that that its color must get “bluer” as it passes through a raindrop. It doesn’t because the frequency remains the same.

We measure frequency by dividing the number of wave crests passing a point per unit time. The extra time light takes to travel through the drop neatly cancels the shortening of wavelength caused by the ray’s drop in speed, preserving the beam’s frequency and thus color. Click HERE for a further explanation.

Why prisms/raindrops bend and separate light

Before we wrap up, there remains an unanswered question tickling in the back of our minds. Why does light bend in the first place when it shines through water or glass? Why not just go straight through? Well, light does pass straight through if it’s perpendicular to the medium. Only if it arrives at an angle from the side will it get bent. It’s similar to watching an incoming ocean wave bend around a cliff. For a nice visual explanation, I recommend the excellent, short video above.

Oh, and Collin, thanks for that question buddy!