The thing with black holes is they’re hard to see. Typically we can only detect their presence when we can detect their gravitational pull. And if there are rogue black holes simply traveling throughout the galaxy and not tied to another luminous astronomical, it would be fiendishly hard to detect them. But now we have a new potential data set to do so.

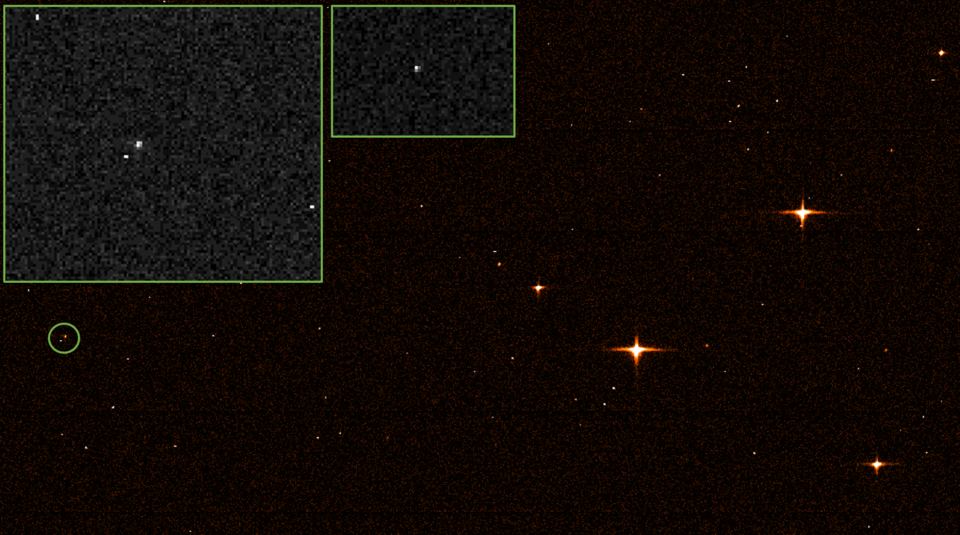

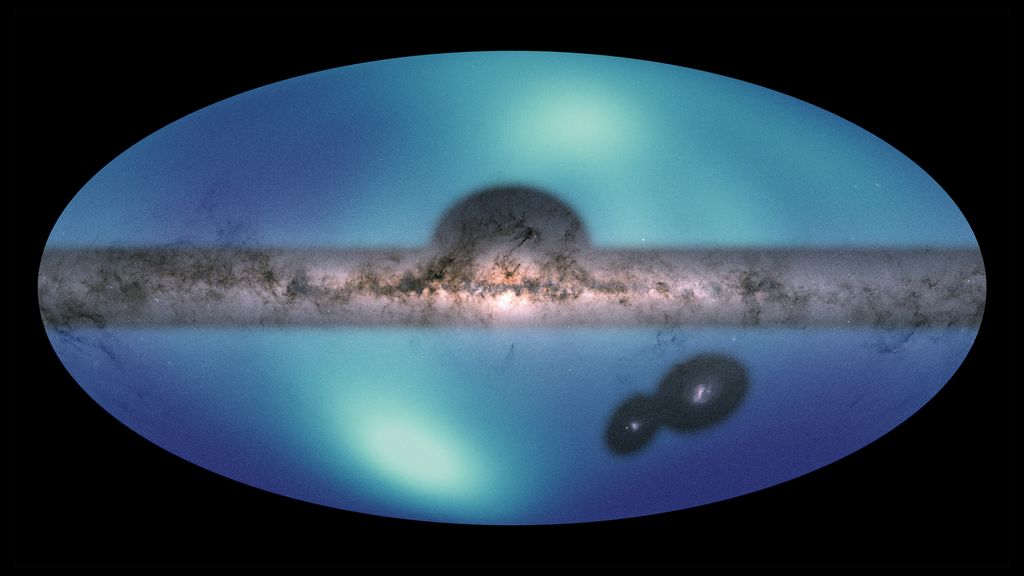

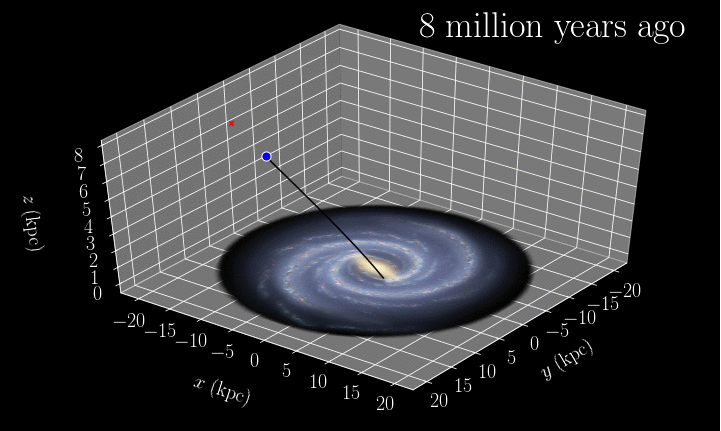

Gaia just released its massive 3rd data set that contains astrometry data for over 1.5 billion stars, about 1% of the total number of stars in the galaxy. According to a new paper by Jeff Andrews of the University of Florida and Northwestern University, it might be possible for Gaia to detect perturbances caused by a rogue black hole briefly interacting with one of the 1.5 billion stars in the catalog. Unfortunately, it’s just not very likely that any such interaction actually took place during Gaia’s observing time.

Continue reading “Gaia Could Detect Free-Floating Black Holes Passing Near Stars in the Milky Way”