Everybody knows that galaxies are enormous collections of stars. A single galaxy can contain hundreds of billions of them. But there is a type of galaxy that has no stars. That’s right: zero stars.

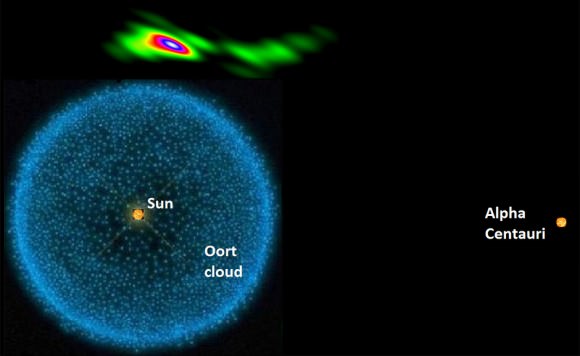

These galaxies are called Dark Galaxies, or Dark Matter Galaxies. And rather than consisting of stars, they consist mostly of Dark Matter. Theory predicts that there should be many of these Dwarf Dark Galaxies in the halo around ‘regular’ galaxies, but finding them has been difficult.

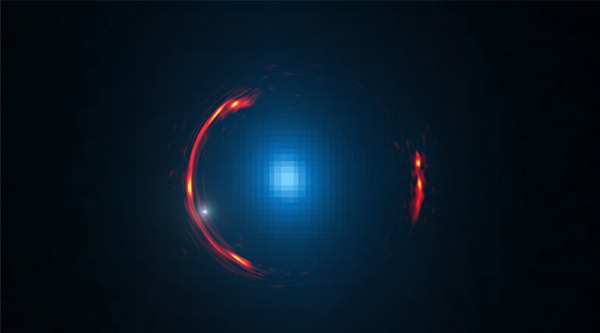

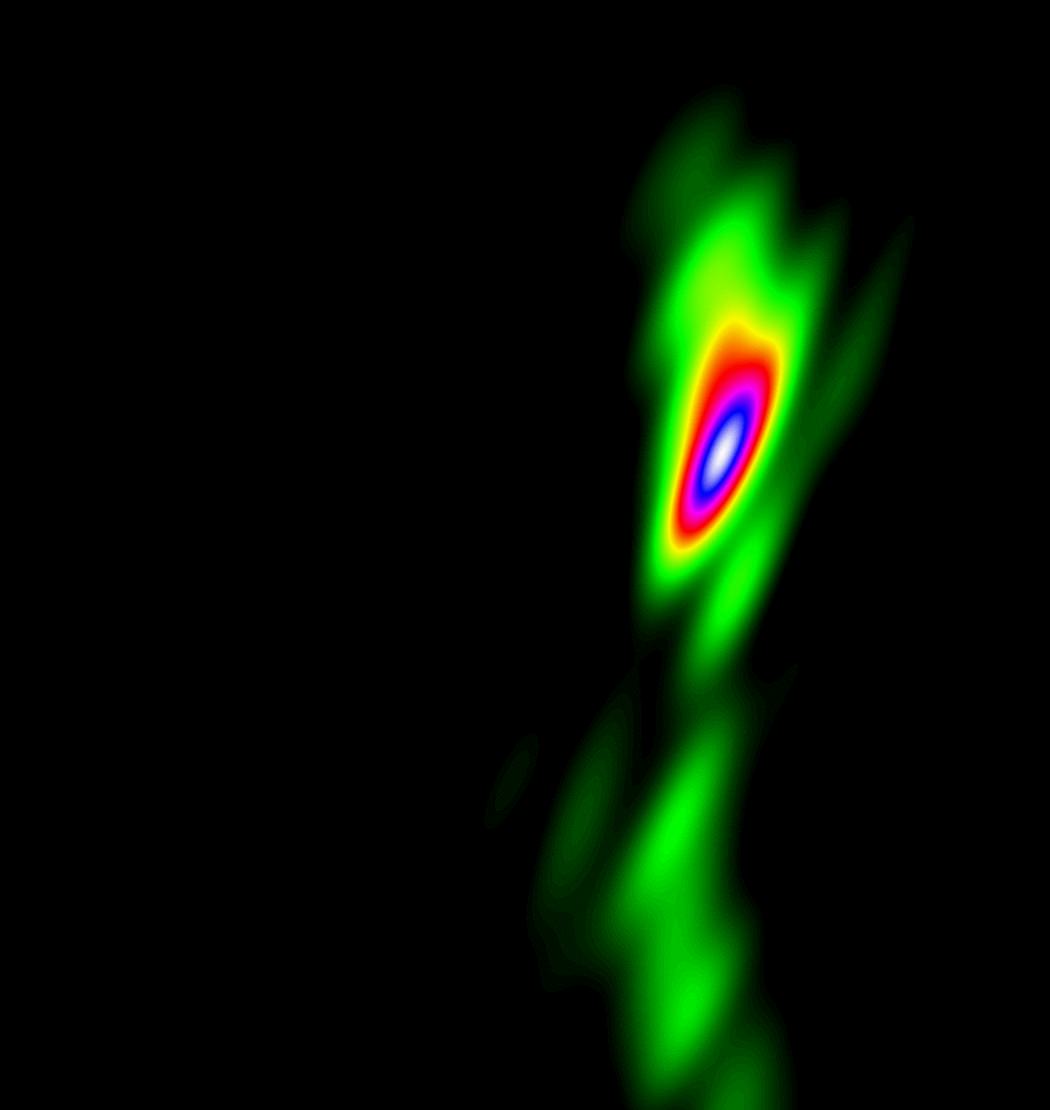

Now, in a new paper to be published in the Astrophysical Journal, Yashar Hezaveh at Stanford University in California, and his team of colleagues, announce the discovery of one such object. The team used enhanced capabilities of the Atacamas Large Millimeter Array to examine an Einstein ring, so named because Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity predicted the phenomenon long before one was observed.

An Einstein Ring is when the massive gravity of a close object distorts the light from a much more distant object. They operate much like the lens in a telescope, or even a pair of eye-glasses. The mass of the glass in the lens directs incoming light in such a way that distant objects are enlarged.

Einstein Rings and gravitational lensing allow astronomers to study extremely distant objects, by looking at them through a lens of gravity. But they also allow astronomers to learn more about the galaxy that is acting as the lens, which is what happened in this case.

If a glass lens had tiny water spots on it, those spots would add a tiny amount of distortion to the image. That’s what happened in this case, except rather than microscopic water drops on a lens, the distortions were caused by tiny Dwarf Galaxies consisting of Dark Matter. “We can find these invisible objects in the same way that you can see rain droplets on a window. You know they are there because they distort the image of the background objects,” explained Hezaveh. The difference is that water distorts light by refraction, whereas matter distorts light by gravity.

As the ALMA facility increased its resolution, astronomers studied different astronomical objects to test its capabilities. One of these objects was SDP81, the gravitational lens in the above image. As they examined the more distant galaxy being lensed by SDP81, they discovered smaller distortions in the ring of the distant galaxy. Hezaveh and his team conclude that these distortions signal the presence of a Dwarf Dark Galaxy.

But why does this all matter? Because there is a problem in the Universe, or at least in our understanding of it; a problem of missing mass.

Our understanding of the formation of the structure of the Universe is pretty solid, at least in the larger scale. Predictions based on this model agree with observations of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) and galaxy clustering. But our understanding breaks down somewhat when it comes to the smaller scale structure of the Universe.

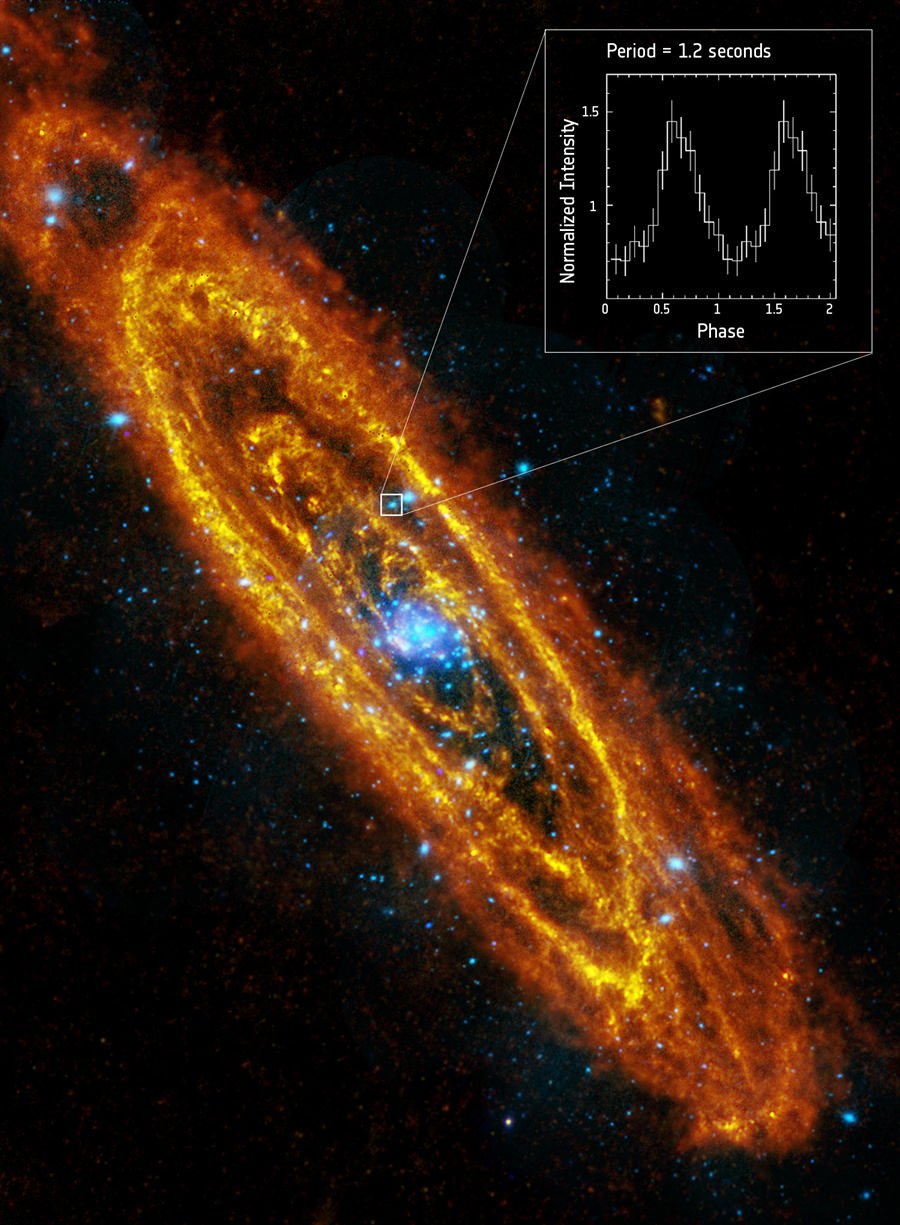

One example of our lack of understanding in this area is what’s known as the Missing Satellite Problem. Theory predicts that there should be a large population of what are called sub-halo objects in the halo of dark matter surrounding galaxies. These objects can range from things as large as the Magellanic Clouds down to much smaller objects. In observations of the Local Group, there is a pronounced deficit of these objects, to the tune of a factor of 10, when compared to theoretical predictions.

Because we haven’t found them, one of two things needs to happen: either we get better at finding them, or we modify our theory. But it seems a little too soon to modify our theories of the structure of the Universe because we haven’t found something that, by its very nature, is hard to find. That’s why this announcement is so important.

The observation and identification of one of these Dwarf Dark Galaxies should open the door to more. Once more are found, we can start to build a model of their population and distribution. So if in the future more of these Dwarf Dark Galaxies are found, it will gradually confirm our over-arching understanding of the formation and structure of the Universe. And it’ll mean we’re on the right track when it comes to understanding Dark Matter’s role in the Universe. If we can’t find them, and the one bound to the halo of SDP81 turns out to be an anomaly, then it’s back to the drawing board, theoretically.

It took a lot of horsepower to detect the Dwarf Dark Galaxy bound to SDP81. Einstein Rings like SDP81 have to have enormous mass in order to exert a gravitational lensing effect, while Dwarf Dark Galaxies are tiny in comparison. It’s a classic ‘needle in a haystack’ problem, and Hezaveh and his team needed massive computing power to analyze the data from ALMA.

ALMA, and the methodology developed by Hezaveh and team will hopefully shed more light on Dwarf Dark Galaxies in the future. The team thinks that ALMA has great potential to discover more of these halo objects, which should in turn improve our understanding of the structure of the Universe. As they say in the conclusion of their paper, “… ALMA observations have the potential to significantly advance our understanding of the abundance of dark matter substructure.”