So, how can galaxies be traveling faster than the speed of light when nothing can travel faster than light?

I’m a little world of contradictions. “Not even light itself can escape a black hole”, and then, “black holes and they are the brightest objects in the Universe”. I’ve also said “nothing can travel faster than the speed of light”. And then I’ll say something like, “ galaxies are moving away from us faster than the speed of light.” There’s more than a few items on this list, and it’s confusing at best. Thanks Universe!

So, how can galaxies be traveling faster than the speed of light when nothing can travel faster than light? Warp speed galaxies come up when I talk about the expansion of the Universe. Perhaps it’s dark energy acceleration, or the earliest inflationary period of the Universe when EVERYTHING expanded faster than the speed of light.

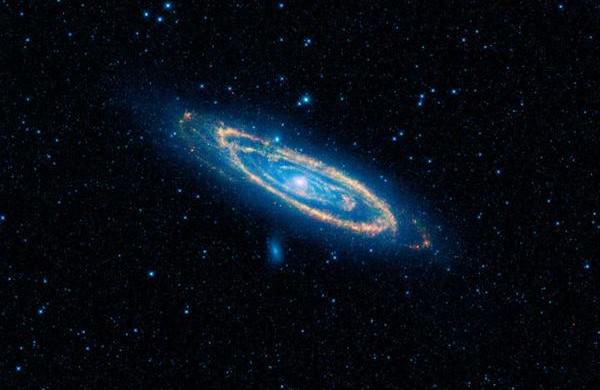

Imagine our expanding Universe. It’s not an explosion from a specific place, with galaxies hurtling out like cosmic jetsam. It’s an expansion of space. There’s no center, and the Universe isn’t expanding into anything.

I’d suggested that this is a terribly oversimplified model for our Universe expanding. Unfortunately, it’s also terribly convenient. I can steal it from my children whenever I want.

Imagine you’re this node here, and as the toy expands, you see all these other nodes moving away from you. And if you were to move to any other node, you’d see all the other nodes moving away from you.

Here’s the interesting part, these nodes over here, twice as far away as the closer ones, appear to move more quickly away from you. The further out the node is, the faster it appears to be moving away from you.

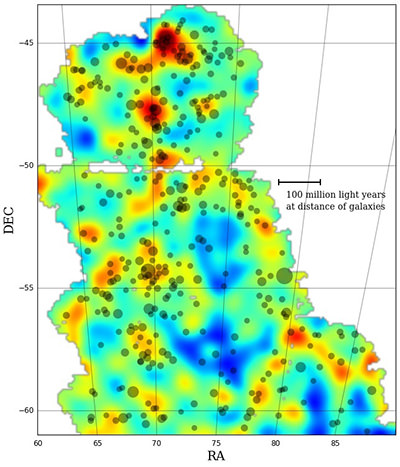

This is our freaky friend, the Hubble Constant, the idea that for every megaparsec of distance between us and a distant galaxy, the speed separating them increases by about 71 kilometers per second.

Galaxies separated by 2 parsecs will increase their speed by 142 kilometers every second. If you run the mathatron, once you get out to 4,200 megaparsecs away, two galaxies will see each other traveling away faster than the speed of light. How big Is that, is it larger than the Universe?

The first light ever, the cosmic microwave background radiation, is 46 billion light-years away from us in all directions. I did the math and 4,200 megaparsecs is a little over 13.7 billion light-years.There’s mountains of room for objects to be more than 4,200 megaparsecs away from each other. Thanks Universe?!?

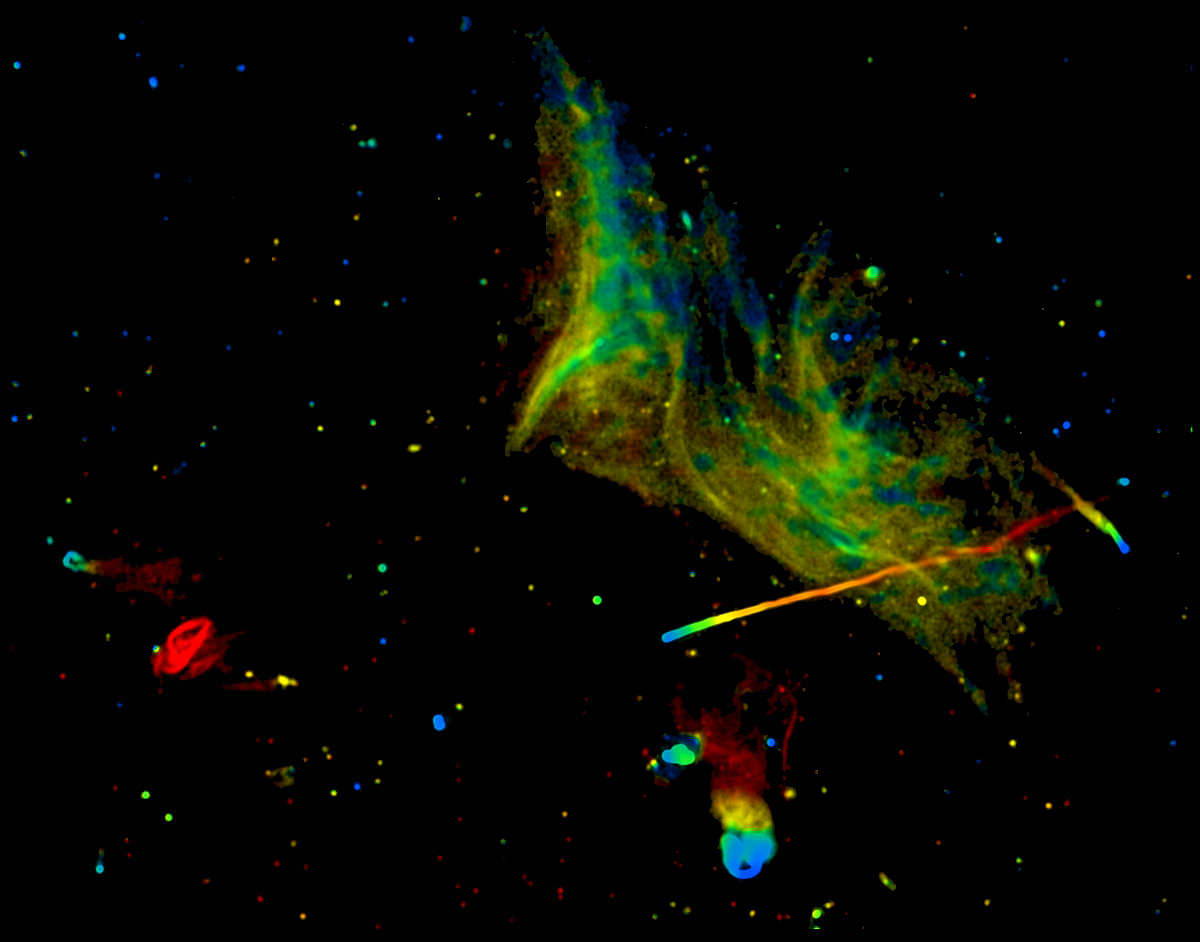

Most of the Universe we can see is already racing away at faster than the speed of light. So how it’s possible to see the light from any galaxies moving faster than the speed of light. How can we even see the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation? Thanks Universe.

Light emitted by the galaxies is moving towards us, while the galaxy itself is traveling away from us, so the photons emitted by all the stars can still reach us. These wavelengths of light get all stretched out, and duckslide further into the red end of the spectrum, off to infrared, microwave, and even radio waves. Given time, the photons will be stretched so far that we won’t be able to detect the galaxy at all.

In the distant future, all galaxies and radiation we see today will have faded away to be completely undetectable. Future astronomers will have no idea that there was ever a Big Bang, or that there are other galaxies outside the Milky Way. Thanks Universe.

I stand with Einstein when I say that nothing can move faster than light through space, but objects embedded in space can appear to expand faster than the speed of light depending on your perspective.

What aspects about cosmology still give you headaches? Give us some ideas for topics in the comments below.