The Universe is expanding. Distant galaxies are moving away from us in all directions. It’s natural to wonder, is everything expanding? Is the Milky Way expanding? What about the Solar System, or even objects here on Earth. Are atoms expanding?

Nope. The only thing expanding is space itself. Imagine the Universe as loaf of raisin bread rising in the oven. As the bread bakes, it’s stretching in all directions – that’s space. But the raisins aren’t growing, they’re just getting carried away from each other as there’s more bread expanding between them.

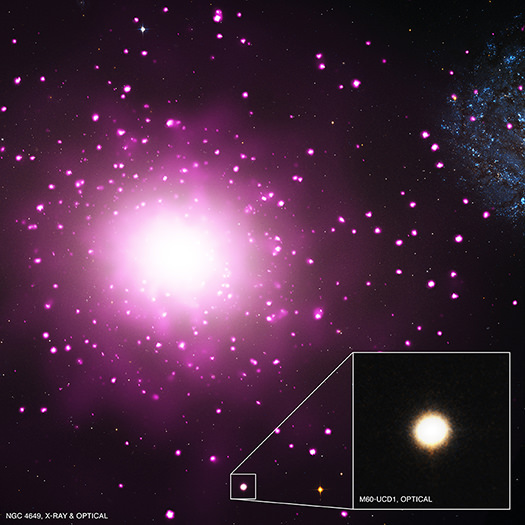

Space is expanding from the Big Bang and the acceleration of dark energy. But the objects embedded in space, like planets, stars, and galaxies stay exactly the same size. As space expands, it carries galaxies away from each other. From our perspective, we see galaxies moving away in every direction. The further galaxies are, the faster they’re moving.

There are a few exceptions. The Andromeda Galaxy is actually moving towards the Milky Way, and will collide with us in about 4 billion years.In this case, the pull of gravity between the Milky Way and Andromeda is so strong that it overcomes the expansion of the Universe on a local level.

Within the Milky Way, gravity holds the stars together, and same with the Solar System. The nuclear force holding atoms together is stronger than this expansion at a local scale. Is this the way it will always be? Maybe. Maybe not.

A few decades ago, astronomers thought that the Universe was expanding because of momentum left over from the Big Bang. But with the discovery of dark energy in 1998, astronomers realized there was a new possibility for the future of the Universe. Perhaps this accelerating dark energy might be increasing over time.

In billions years from now, the expansive force might overcome the gravity that holds galaxies together. Eventually it would become so strong that star systems, planets and eventually matter itself could get torn apart.This is a future for the Universe known as the Big Rip. And if it’s true, then the space between stars, planets and even atoms will expand in the far future.

Is this going to happen? Astronomers don’t know. Their best observations so far can’t rule it out, or confirm it. And so, future observations and space missions will try to calculate the rate of dark energy’s expansion.

So no, matter on a local level isn’t expanding. The spaces between planets and stars isn’t growing. Only the distances between galaxies which aren’t gravitationally bound to each other is increasing. Because space itself is expanding.