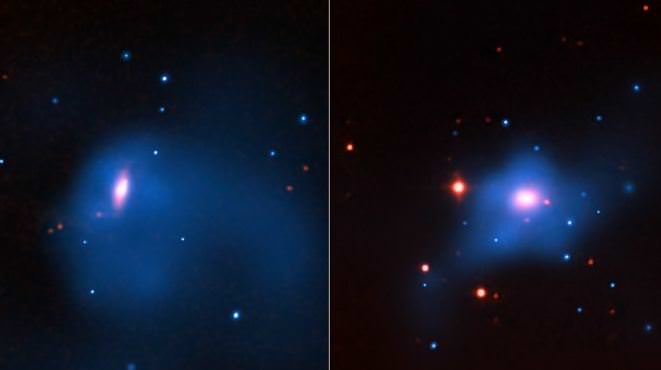

The image above looks like a classic example of a collision between two galaxies. However, Hubble scientists have determined, this is just an illusion, a trick of perspective. The two galaxies, NGC 3314A and B are actually tens of millions of light years apart instead of merging in a galactic pileup. From our vantage point on Earth the two just happen to appear to be overlapping at great distances from each other.

How did the Hubble scientists figure this out? The biggest hint as to whether galaxies are interacting is usually their shapes. The immense gravitational forces involved in galactic mergers are enough to pull a galaxy out of shape long before it actually collides. Deforming a galaxy like this does not just warp its structure, but it can trigger new episodes of star formation, usually visible as bright blue stars and glowing nebulae.

In the case of NGC 3314, there is some deformation in the foreground galaxy (called NGC 3314A, NGC 3314B lies in the background), but the Hubble team says this is almost certainly misleading. NGC 3314A’s deformed shape, particularly visible below and to the right of the core, where streams of hot blue-white stars extend out from the spiral arms, is not due to interaction with the galaxy in the background.

Studies of the motion of the two galaxies indicate that they are both relatively undisturbed, and that they are moving independently of each other. This indicates in turn that they are not, and indeed have never been, on any collision course. NGC 3314A’s warped shape is likely due instead to an encounter with another galaxy, perhaps nearby NGC 3312 (visible to the north in wide-field images) or another nearby galaxy.

The chance alignment of the two galaxies is more than just a curiosity, though. It greatly affects the way the two galaxies appear to us.

NGC 3314B’s dust lanes, for example, appear far lighter than those of NGC 3314A. This is not because that galaxy lacks dust, but rather because they are lightened by the bright fog of stars in the foreground. NGC 3314A’s dust, in contrast, is backlit by the stars of NGC 3314B, silhouetting them against the bright background.

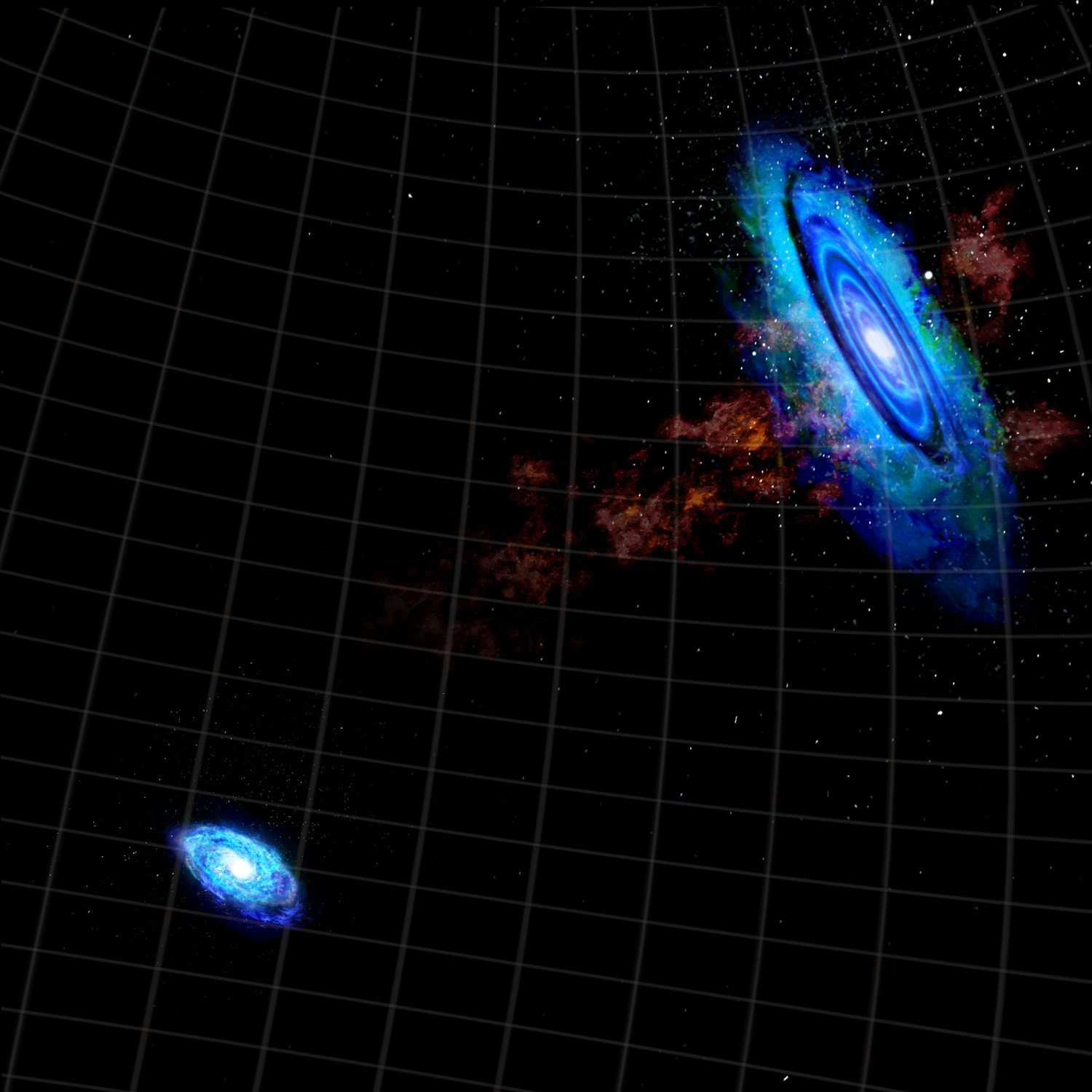

Such an alignment of galaxies is also helpful to astronomers studying gravitational microlensing, a phenomenon that occurs when stars in one galaxy cause small perturbations in the light coming from a more distant one. Indeed, the observations of NGC 3314 that led to this image were carried out in order to investigate this phenomenon.

This mosaic image covers a large field of view (several times the size of an individual exposure from Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys). Thanks to a long exposure time of more than an hour in total exposure time for every frame, the image shows not only NGC 3314, but also many other more distant galaxies in the background.

The color composite was produced from exposures taken in blue and red light.

Image caption: The Hubble Space Telescope has produced an incredibly detailed image of a pair of overlapping galaxies called NGC 3314. While the two galaxies look as if they are in the midst of a collision, this is in fact a trick of perspective: the two are in chance alignment from our vantage point.

Credit:

NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage (STScI/AURA)-ESA/Hubble Collaboration, and W. Keel (University of Alabama)

Source: ESA