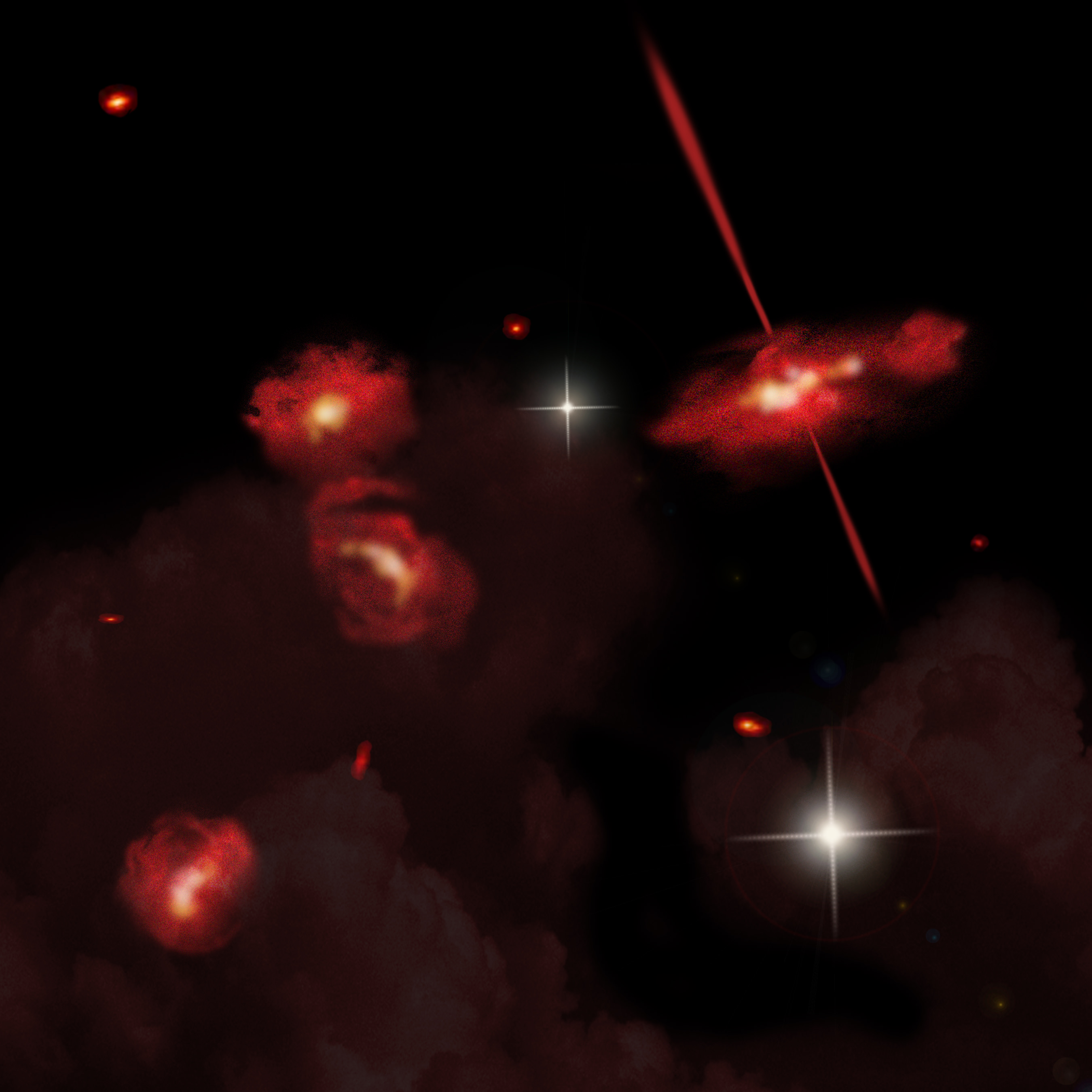

[/caption]A team of astronomers, led by Jiasheng Huang (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) using the Spitzer Space Telescope, have discovered four ‘Ultra-Red’ galaxies that formed when our Universe was about a billion years old. Huang and his team used several computer models in an attempt to understand why these galaxies appear so red, stating, “We’ve had to go to extremes to get the models to match our observations.”

The results of Huang’s research were recently published in The Astrophysical Journal

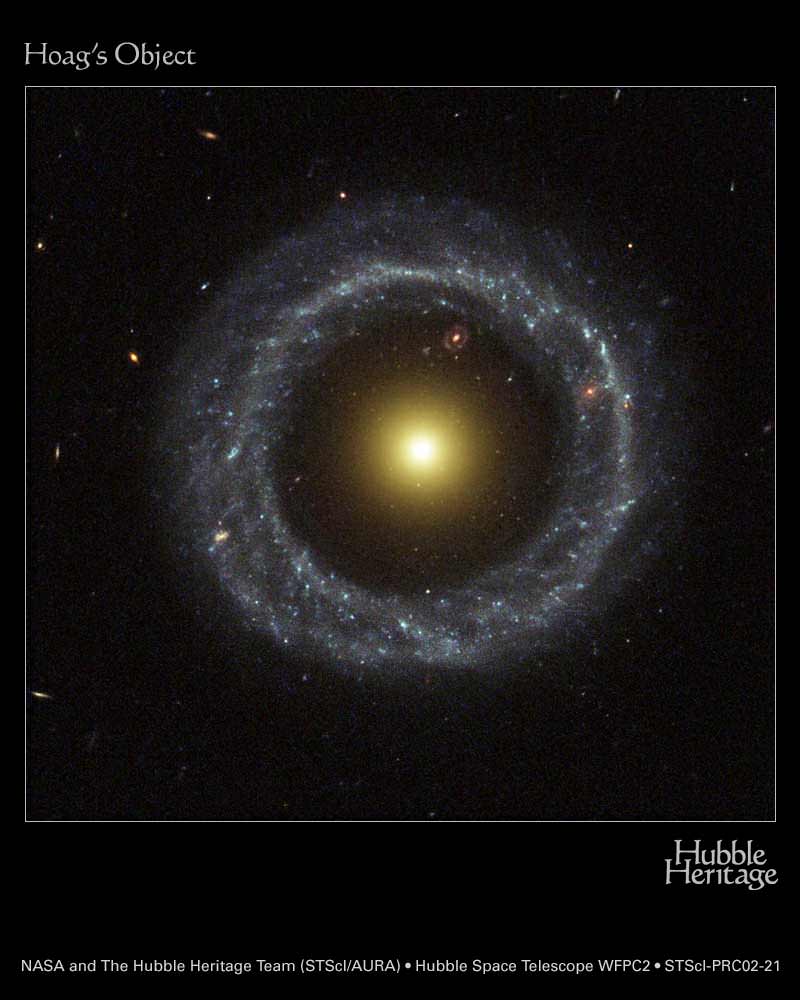

Using the Spitzer Space Telescope helped make the discovery possible, as it is more sensitive to infrared light than other space telescopes such as the Hubble. The newly discovered galaxies are sixty times brighter in the infrared than they are at the longest/reddest wavelengths HST can detect.

What processes are at work to create these extremely red objects, and why are they of interest to astronomers?

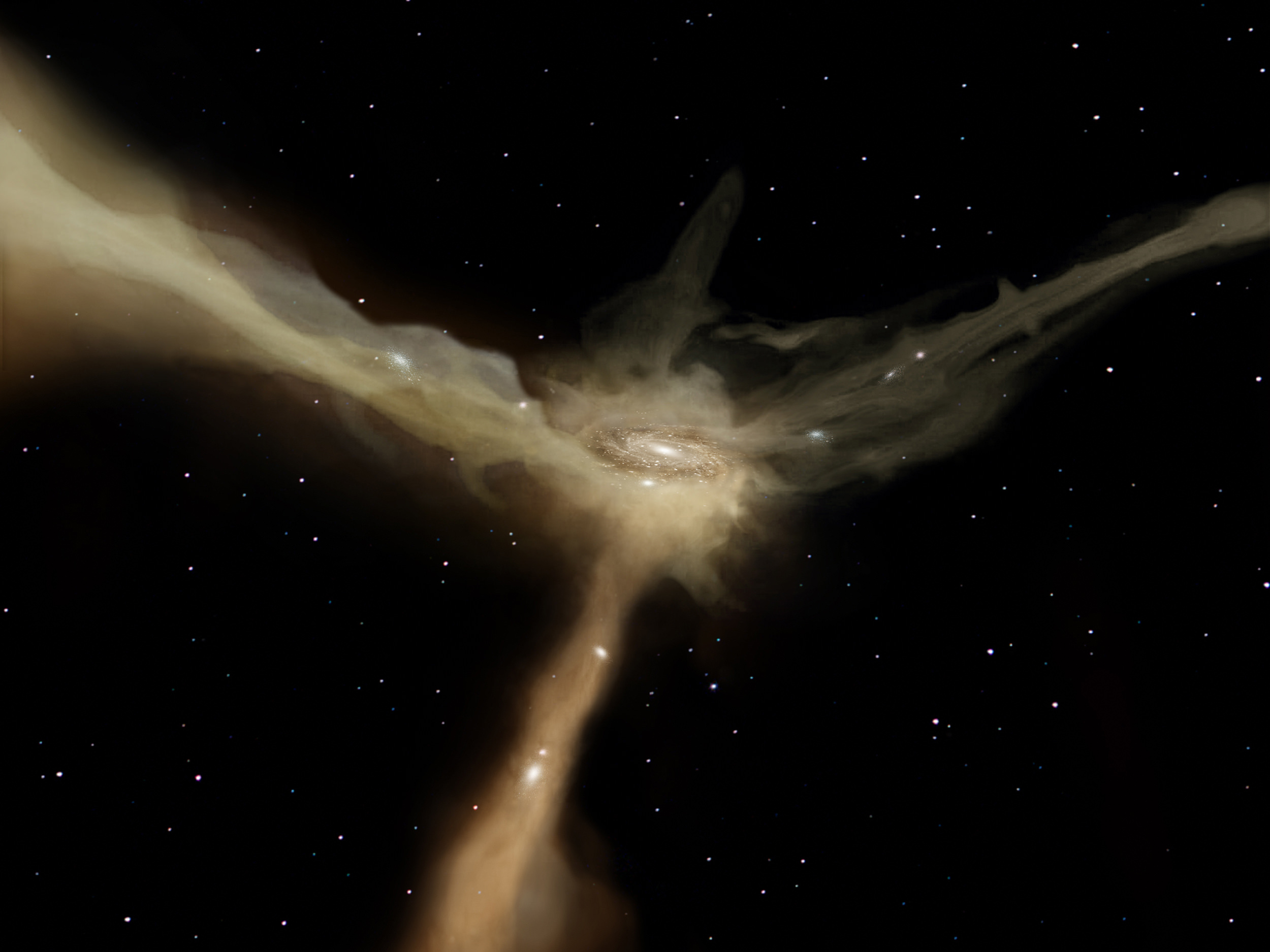

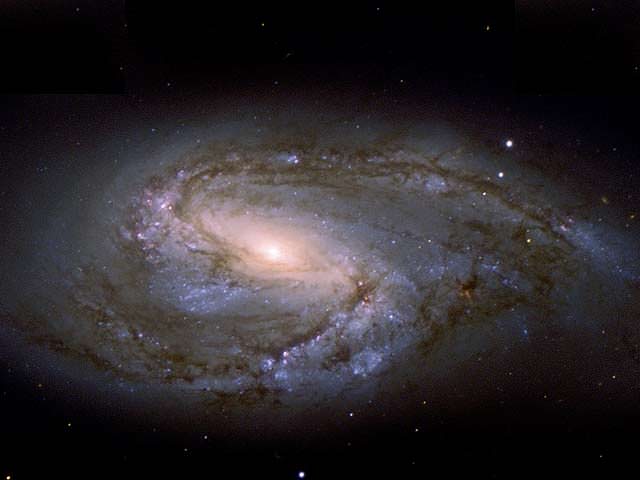

There are several reasons a galaxy could be reddened. For starters, extremely distant galaxies can have their light “redshifted” due to the expansion of the universe. If a galaxy contains large amounts of dust, it will also appear redder than a galaxy with less dust. Lastly, older galaxies will tend to be redder, due to a higher concentration of old, red stars and less younger bluer stars.

According to the paper, Huang and his team created three models to determine why these galaxies appear so red. Of their models, the one which suggests an old stellar population is currently the best fit to the observations. Supporting this conclusion, co-author Giovanni Fazio stated, “Hubble has shown us some of the first protogalaxies that formed, but nothing that looks like this. In a sense, these galaxies might be a ‘missing link’ in galactic evolution”.

Studying these extremely distant galaxies helps provide astronomers with a better understanding of the early universe, specifically how early galaxies formed and what conditions were present when some of the first stars were created. The next step in understanding these “ERO” galaxies is to obtain an accurate redshift for the galaxies, by using more powerful telescopes such as the Large Millimeter Telescope or Atacama Large Millimeter Array.

Huang and his team have plans to search for more galaxies similar to the four recently discovered by his team. Huang’s co-author Giovanni Fazio adds, “There’s evidence for others in other regions of the sky. We’ll analyze more Spitzer and Hubble observations to track them down.”

If you’d like to learn more, you can access the full paper (via arXiv.org) at: http://arxiv.org/pdf/1110.4129v1

Source: Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics press release , arxiv.org