[/caption]

Using the Hubble Space Telescope and the Very Large Telescope (VLT), astronomers have looked back to find the most distant galaxy so far. “We are observing a galaxy that existed essentially when the Universe was only about 600 million years old, and we are looking at this galaxy – and the Universe – 13.1 billion years ago,” said Dr. Matt Lehnert from the Observatoire de Paris, who is the lead author of a new paper in Nature. “Conditions were quite different back then. The basic picture in which this discovery is embedded is that this is the epoch in which the Universe went from largely neutral to basically ionized.”

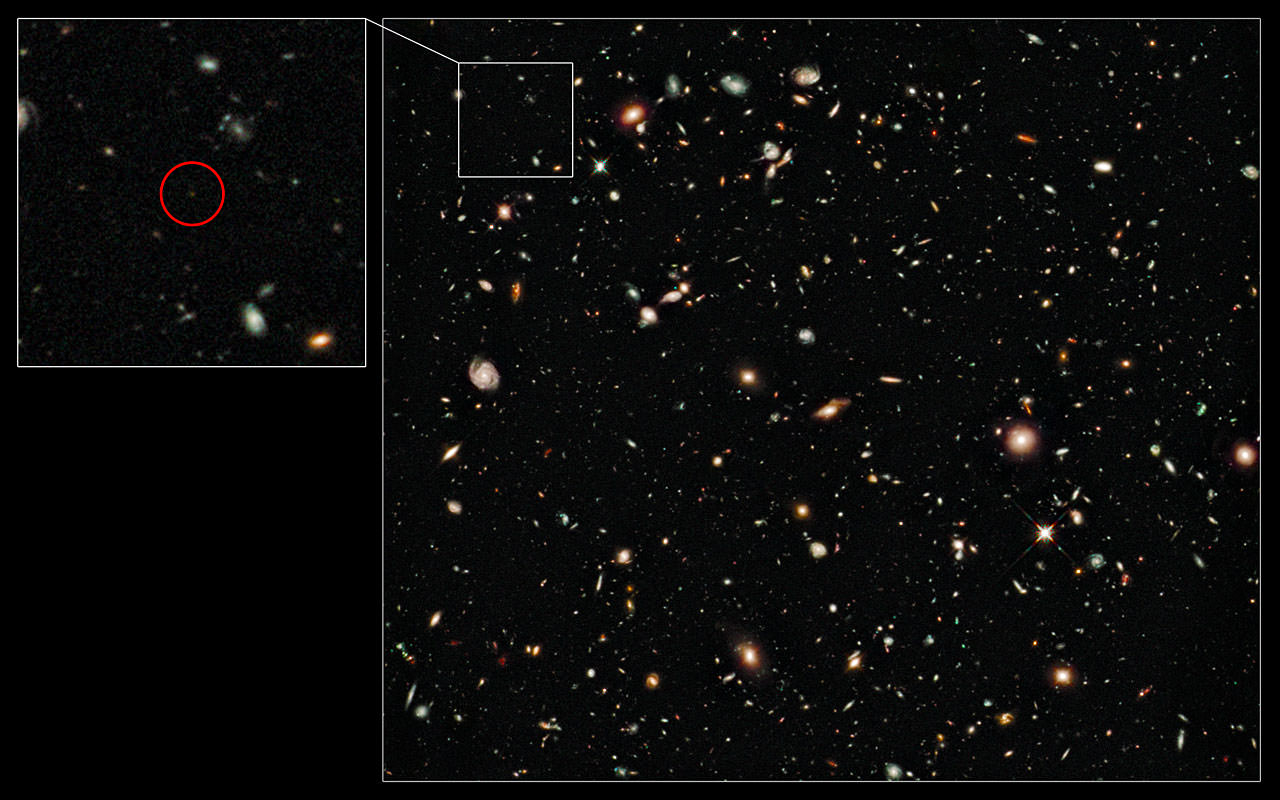

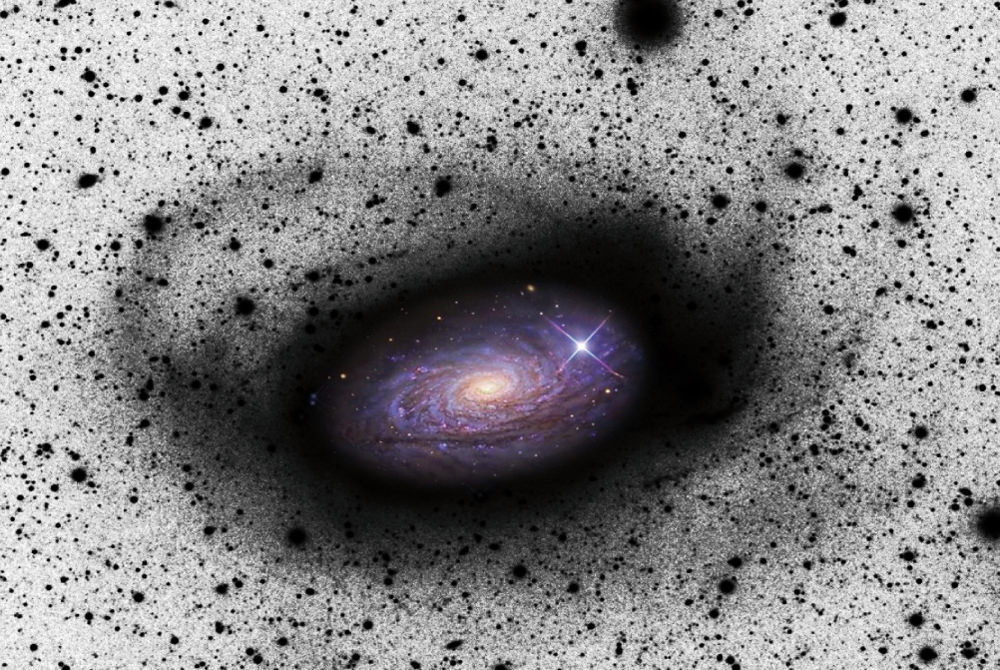

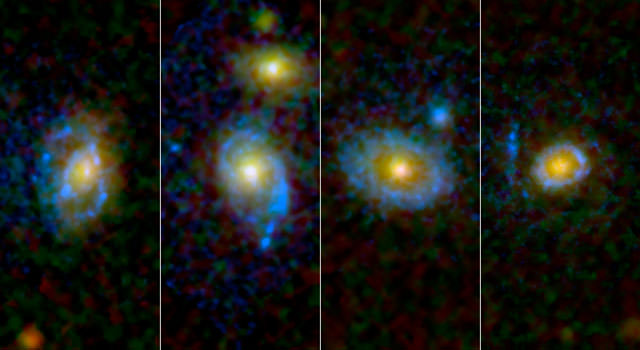

Lehnert and an international team used the VLT to make follow-up observations of the galaxy — called UDFy-38135539 – which Hubble observations in 2009 had revealed. The astronomers analyzed the very faint glow of the galaxy to measure its distance — and age. This is the first confirmed observations of a galaxy whose light is emerging from the reionization of the Universe.

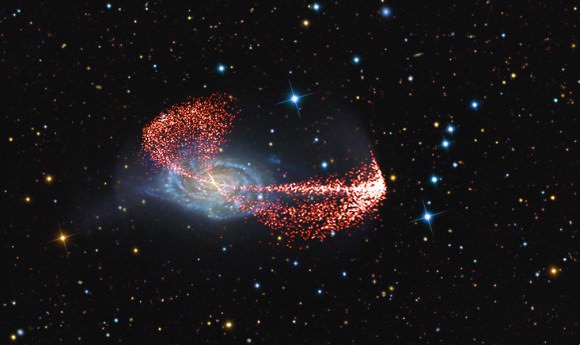

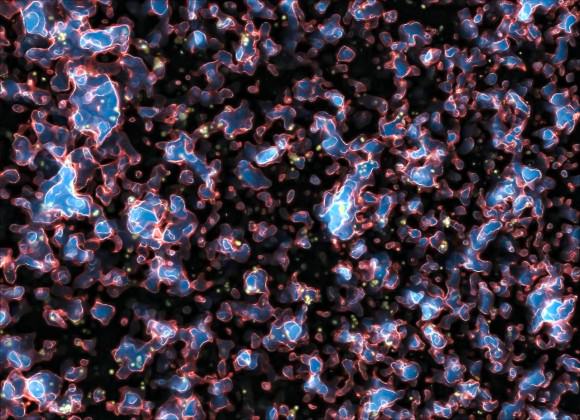

The reionization period is about the farthest back in time that astronomers can observe. The Big Bang, 13.7 billion years ago, created a hot, murky universe. Some 400,000 years later, temperatures cooled, electrons and protons joined to form neutral hydrogen, and the murk cleared. Some time before 1 billion years after the Big Bang, neutral hydrogen began to form stars in the first galaxies, which radiated energy and changed the hydrogen back to being ionized. Although not the thick plasma soup of the earlier period just after the Big Bang, this galaxy formation started the reionization epoch, clearing the opaque hydrogen fog that filled the cosmos at this early time.

“The whole history of the Universe is from the reionization,” Lehnert said during an online press briefing. “The dark matter that pervades the Universe began to drag the gas along and formed the first galaxies. When the galaxies began to form, it reionized the Universe.”

UDFy-38135539 is about 100 million light-years farther than the previous most distant object, a gamma-ray burst.

Studying these first galaxies is extremely difficult, Lehnert said, as the dim light falls mostly in the infrared part of the spectrum because its wavelength has been stretched by the expansion of the Universe — an effect known as redshift. During the time of less than a billion years after the Big Bang, the hydrogen fog that pervaded the Universe absorbed the fierce ultraviolet light from young galaxies.

The new Wide Field Camera 3 on the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope discovered several candidate objects in 2009, and with 16 hours of observations using the VLT, the team was able to was used to detect the very faint glow from hydrogen at a redshift of 8.6.

The team used the SINFONI infrared spectroscopic instrument on the VLT and a very long exposure time.

“Measuring the redshift of the most distant galaxy so far is very exciting in itself,” said co-author Nicole Nesvadba (Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale), “but the astrophysical implications of this detection are even more important. This is the first time we know for sure that we are looking at one of the galaxies that cleared out the fog which had filled the very early Universe.”

One of the surprising things about this discovery is that the glow from UDFy-38135539 seems not to be strong enough on its own to clear out the hydrogen fog. “There must be other galaxies, probably fainter and less massive nearby companions of UDFy-38135539,” said co-author Mark Swinbank from Durham University, “which also helped make the space around the galaxy transparent. Without this additional help the light from the galaxy, no matter how brilliant, would have been trapped in the surrounding hydrogen fog and we would not have been able to detect it.”

Sources: ESO, press briefing