[/caption]

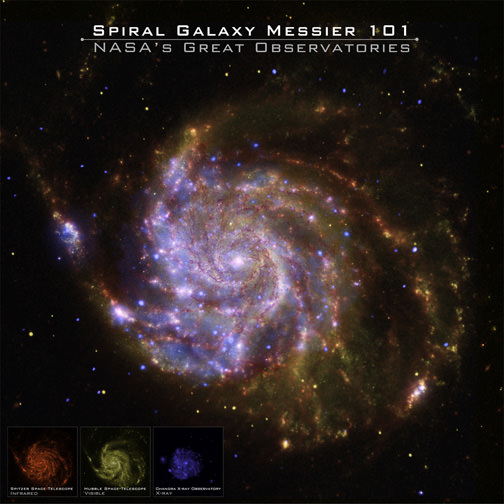

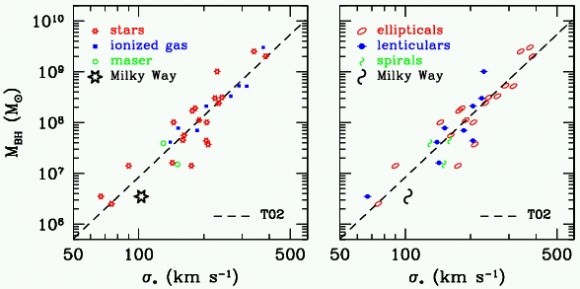

While only observable by inference, the existence of supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at the centre of most – if not all – galaxies remains a compelling theory supported by a range of indirect observational methods. Within these data sources, there exists a strong correlation between the mass of the galactic bulge of a galaxy and the mass of its central SMBH – meaning that smaller galaxies have smaller SMBHs and bigger galaxies have bigger SMBHs.

Linked to this finding is the notion that SMBHs may play an intrinsic role in galaxy formation and evolution – and might have even been the first step in the formation of the earliest galaxies in the universe, including the proto-Milky Way.

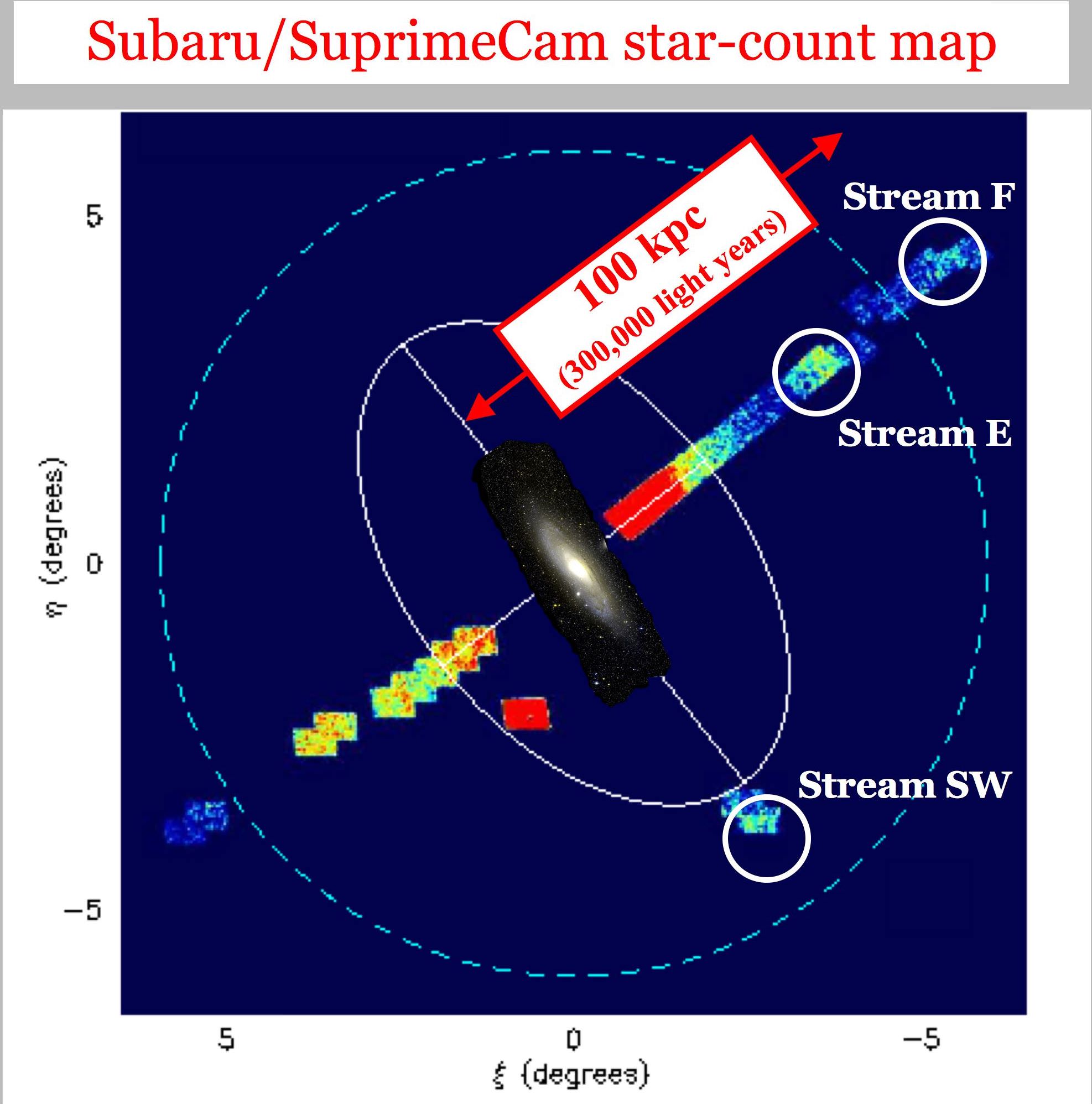

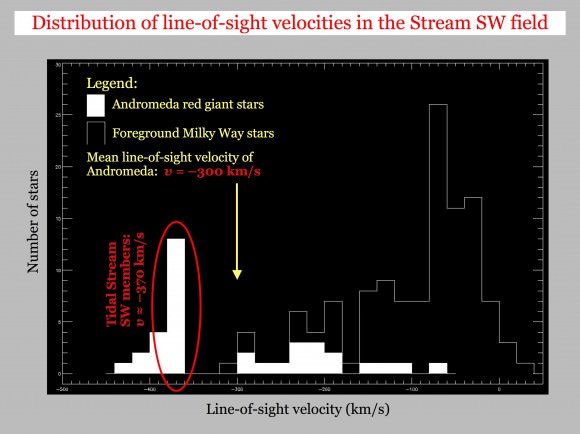

Now, there are a number of significant assumptions built into this line of thinking, since the mass of a galactic bulge is generally inferred from the velocity dispersion of its stars – while the presence of supermassive black holes in the centre of such bulges is inferred from the very fast radial motion of inner stars – at least in closer galaxies where we can observe individual stars.

For galaxies too far away to observe individual stars – the velocity dispersion and the presence of a central supermassive black hole are both inferred – drawing on the what we have learnt from closer galaxies, as well as from direct observations of broad emission lines – which are interpreted as the product of very rapid orbital movement of gas around an SMBH (where the ‘broadening’ of these lines is a result of the Doppler effect).

But despite the assumptions built on assumptions nature of this work, ongoing observations continue to support and hence strengthen the theoretical model. So, with all that said – it seems likely that, rather than depleting its galactic bulge to grow, both an SMBH and the galactic bulge of its host galaxy grow in tandem.

It is speculated that the earliest galaxies, which formed in a smaller, denser universe, may have started with the rapid aggregation of gas and dust, which evolved into massive stars, which evolved into black holes – which then continued to grow rapidly in size due to the amount of surrounding gas and dust they were able to accrete.

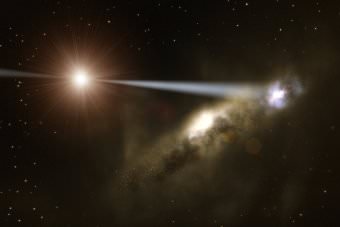

Distant quasars may be examples of such objects which have grown to a galactic scale. However, this growth becomes self-limiting as radiation pressure from an SMBH’s accretion disk and its polar jets becomes intense enough to push large amounts of gas and dust out beyond the growing SMBH’s sphere of influence. That dispersed material contains vestiges of angular momentum to keep it in an orbiting halo around the SMBH and it is in these outer regions that star formation is able to take place. Thus a dynamic balance is reached where the more material an SMBH eats, the more excess material it blows out – contributing to the growth of the galaxy that is forming around it.

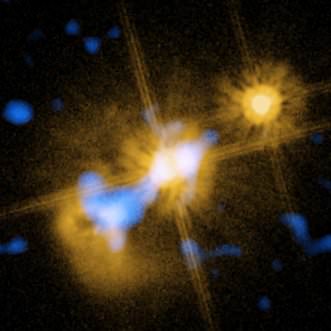

To further investigate the evolution of the relationship between SMBHs and their host galaxies – Nesvadba et al looked at a collection of very red-shifted (and hence very distant) radio galaxies (or HzRGs). They speculate that their selected group of galaxies have reached a critical point – where the feeding frenzy of the SMBH is blowing out about as much material as it is taking in – a point which probably represents the limit of the active growth of the SMBH and its host galaxy.

From that point, such galaxies might grow further by cannibalistic merging – but again this may lead to a co-evolution of the galaxy and the SMBH – as much of the contents of the galaxy being eaten gets used up in star formation within the feasting galaxy’s disk and bulge, before whatever is left gets through to feed the central SMBH.

Other authors (e.g. Schulze and Gebhardt), while not disputing the general concept, suggest that all the measurements are a bit out as a result of not incorporating dark matter into the theoretical model. But, that is another story…

Further reading: Nesvadba et al. The black holes of radio galaxies during the “Quasar Era”: Masses, accretion rates, and evolutionary stage.