[/caption]

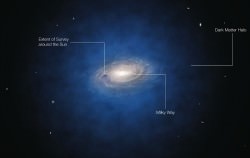

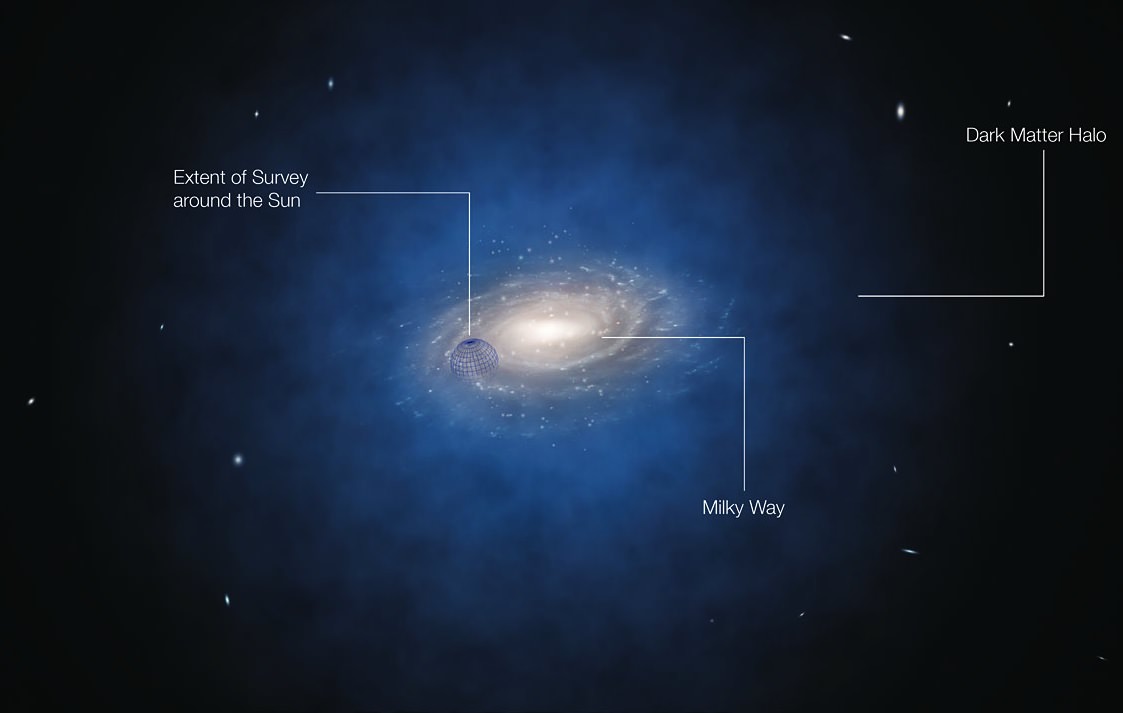

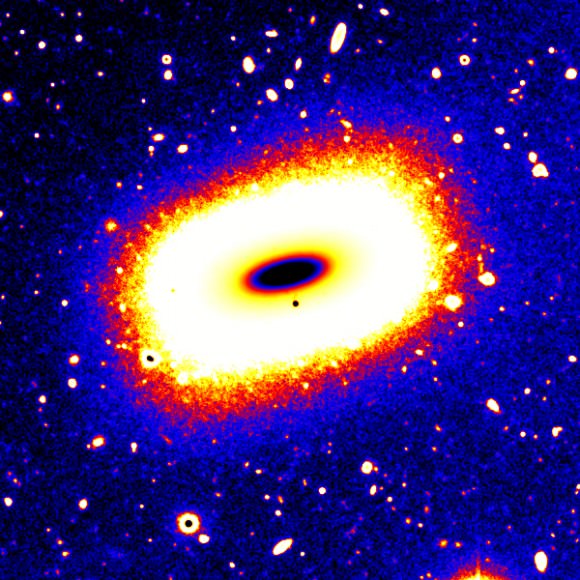

The concept of nomad planets has been featured before here on Universe Today, and for good reason. Not only is the idea of mysterious lone planets drifting sunless through interstellar space an intriguing one, but also the sheer potential quantity of such worlds is simply staggering. If some very well-respected scientists’ calculations are correct there are more nomad planets in our Milky Way galaxy than there are stars — a lot more. With estimates up to 100,000 nomad planets for every star in the galaxy, there could be literally quadrillions of wandering worlds out there, ranging in size from Pluto-sized to even larger than Jupiter.

That’s a lot of nomads. But where did they all come from?

Recently, The Kavli Foundation had a discussion with several scientists involved in nomad planet research. Roger D. Blandford, Director of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC) at Stanford University, Dimitar D. Sasselov, Professor of Astronomy at Harvard University and Louis E. Strigari, Research Associate at KIPAC and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory talked about their findings and what sort of worlds these nomad planets might be, as well as how they may have formed.

One potential source for nomad planets is forceful ejection from solar systems.

“Most stars form in clusters, and around many stars there are protoplanetary disks of gas and dust in which planets form and then potentially get ejected in various ways,” said Strigari. “If these early-forming solar systems have a large number of planets down to the mass of Pluto, you can imagine that exchanges could be frequent.”

And the possibility of planetary formation outside of stellar disks is not entirely ruled out by the researchers — although they do impose a lower limit to the size of such worlds.

“Theoretical calculations say that probably the lowest-mass nomad planet that can form by that process is something around the mass of Jupiter,” said Strigari. “So we don’t expect that planets smaller than that are going to form independent of a developing solar system.”

“This is the big mystery that surrounds this new paper. How do these smaller nomad planets form?” Sasselov added.

Of course, without a sun of their own to supply heat and energy one might assume such worlds would be cold and inhospitable to life. But, as the researchers point out, that may not always be the case. A nomad planet’s internal heat could supply the necessary energy to fuel the emergence of life… or at least keep it going.

“If you imagine the Earth as it is today becoming a nomad planet… life on Earth is not going to cease,” said Sasselov. “That we know. It’s not even speculation at this point. …scientists already have identified a large number of microbes and even two types of nematodes that survive entirely on the heat that comes from inside the Earth.”

Researcher Roger Blandford also suggested that “small nomad planets could retain very dense, high-pressure ‘blankets’ around them. These could conceivably include molecular hydrogen atmospheres or possibly surface ice that would trap a lot of heat. They might be able to keep water liquid, which would be conducive to creating or sustaining life.”

And so with all these potentially life-sustaining planets knocking about the galaxy, is it possible that they could have helped transport organisms from one solar system to another? It’s a concept called panspermia, and it’s been around since at least the 5th century BCE when the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras first wrote about it. (We’ve written about it too, as recently as three weeks ago, and it’s still a much-debated topic.)

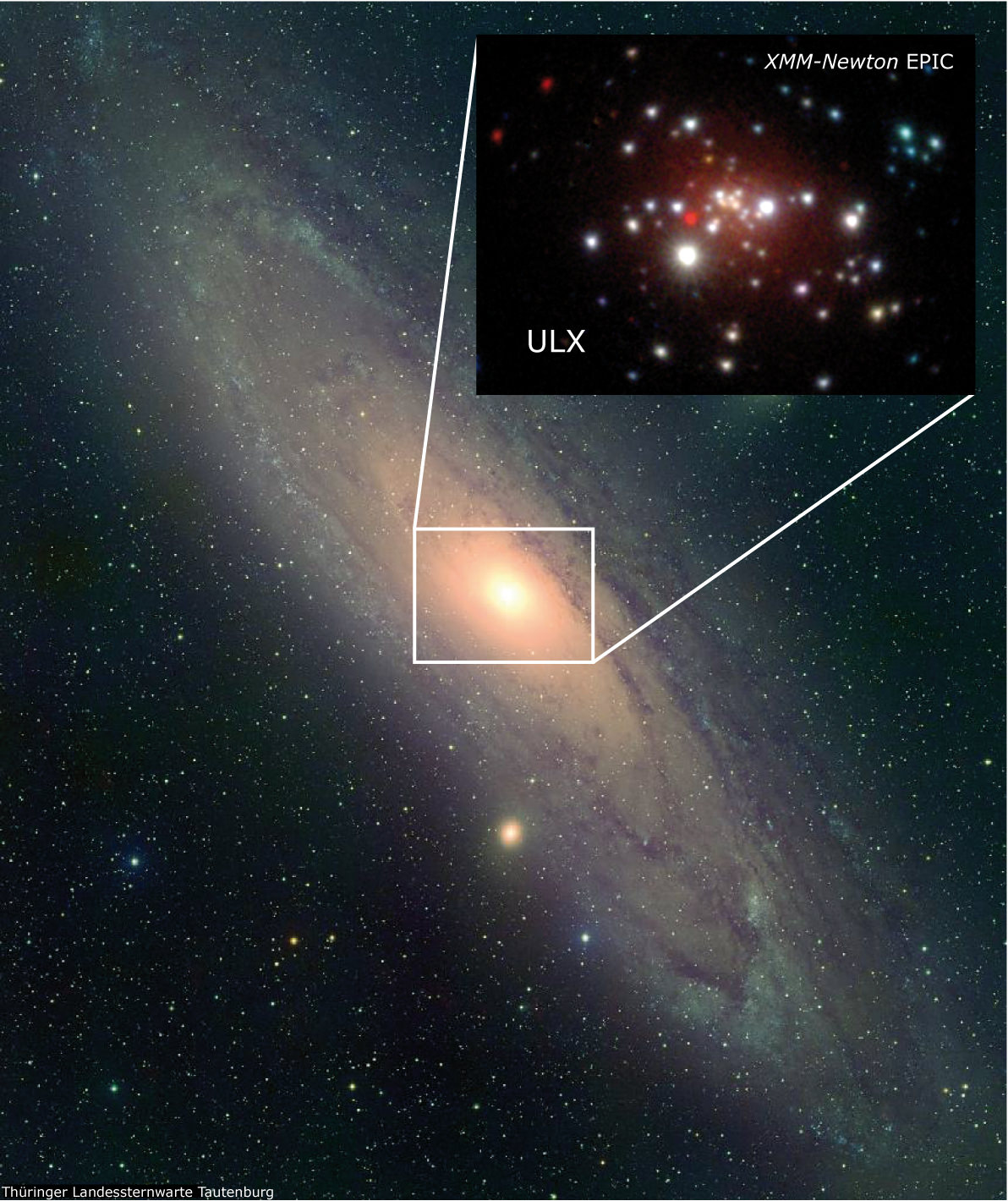

“In the 20th century, many eminent scientists have entertained the speculation that life propagated either in a directed, random or malicious way throughout the galaxy,” said Blandford. “One thing that I think modern astronomy might add to that is clear evidence that many galaxies collide and spray material out into intergalactic space. So life can propagate between galaxies too, in principle.

“And so it’s a very old speculation, but it’s a perfectly reasonable idea and one that is becoming more accessible to scientific investigation.”

Nomad planets may not even be limited to the confines of the Milky Way. Given enough of a push, they could be sent out of the galaxy entirely.

“Just a stellar or black hole encounter within the galaxy can, in principle, give a planet the escape velocity it needs to be ejected from the galaxy. If you look at galaxies at large, collisions between them leads a lot of material being cast out into intergalactic space,” Blandford said.

The discussion is a fascinating one and can be found in its entirety on The Kavli Foundation’s site here, and watch a recorded interview between Louis Strigari and journalist Bruce Lieberman here.

The Kavli Foundation, based in Oxnard, California, is dedicated to the goals of advancing science for the benefit of humanity and promoting increased public understanding and support for scientists and their work.