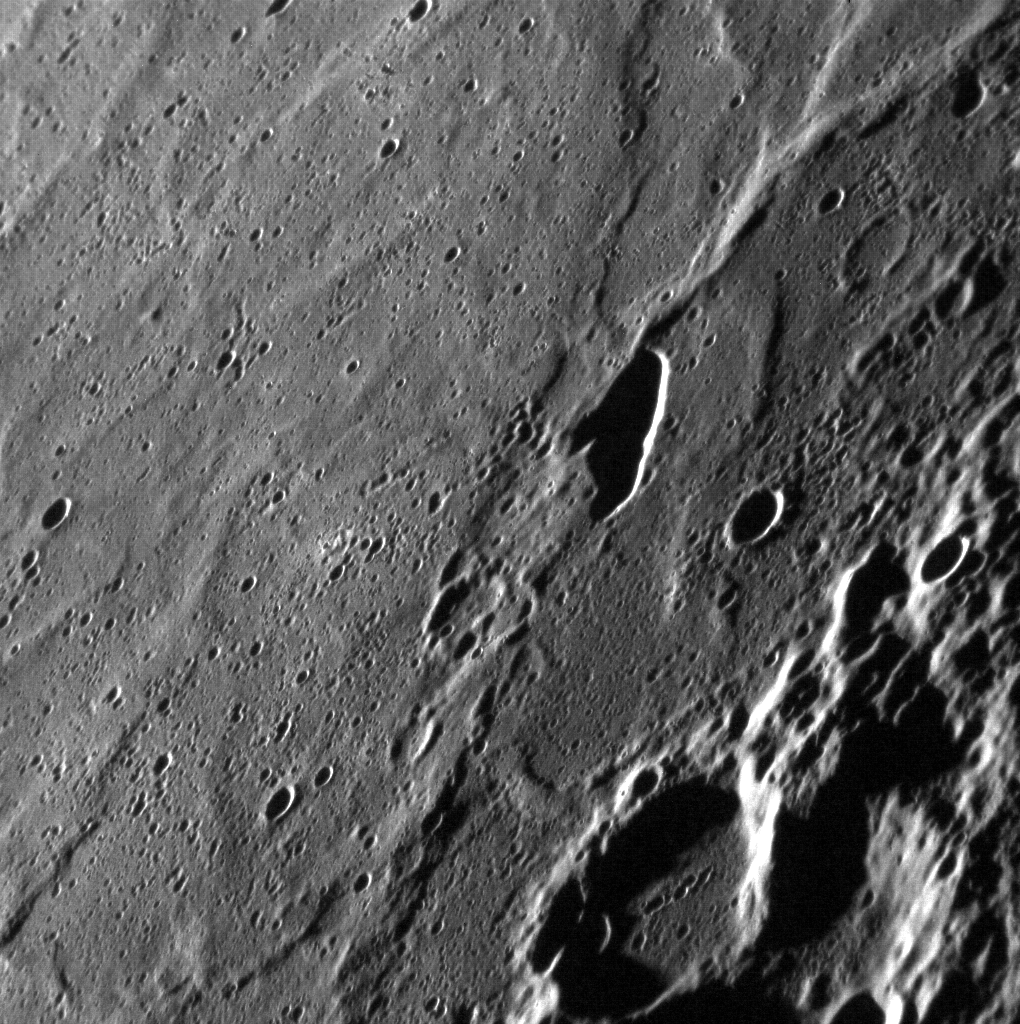

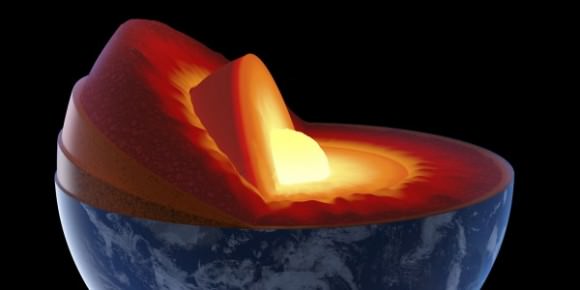

There is more to the Earth than what we can see on the surface. In fact, if you were able to hold the Earth in your hand and slice it in half, you’d see that it has multiple layers. But of course, the interior of our world continues to hold some mysteries for us. Even as we intrepidly explore other worlds and deploy satellites into orbit, the inner recesses of our planet remains off limit from us.

However, advances in seismology have allowed us to learn a great deal about the Earth and the many layers that make it up. Each layer has its own properties, composition, and characteristics that affects many of the key processes of our planet. They are, in order from the exterior to the interior – the crust, the mantle, the outer core, and the inner core. Let’s take a look at them and see what they have going on.

Modern Theory:

Like all terrestrial planets, the Earth’s interior is differentiated. This means that its internal structure consists of layers, arranged like the skin of an onion. Peel back one, and you find another, distinguished from the last by its chemical and geological properties, as well as vast differences in temperature and pressure.

Our modern, scientific understanding of the Earth’s interior structure is based on inferences made with the help of seismic monitoring. In essence, this involves measuring sound waves generated by earthquakes, and examining how passing through the different layers of the Earth causes them to slow down. The changes in seismic velocity cause refraction which is calculated (in accordance with Snell’s Law) to determine differences in density.

These are used, along with measurements of the gravitational and magnetic fields of the Earth and experiments with crystalline solids that simulate pressures and temperatures in the Earth’s deep interior, to determine what Earth’s layers looks like. In addition, it is understood that the differences in temperature and pressure are due to leftover heat from the planet’s initial formation, the decay of radioactive elements, and the freezing of the inner core due to intense pressure.

History of Study:

Since ancient times, human beings have sought to understand the formation and composition of the Earth. The earliest known cases were unscientific in nature – taking the form of creation myths or religious fables involving the gods. However, between classical antiquity and the medieval period, several theories emerged about the origin of the Earth and its proper makeup.

Most of the ancient theories about Earth tended towards the “Flat-Earth” view of our planet’s physical form. This was the view in Mesopotamian culture, where the world was portrayed as a flat disk afloat in an ocean. To the Mayans, the world was flat, and at it corners, four jaguars (known as bacabs) held up the sky. The ancient Persians speculated that the Earth was a seven-layered ziggurat (or cosmic mountain), while the Chinese viewed it as a four-side cube.

By the 6th century BCE, Greek philosophers began to speculate that the Earth was in fact round, and by the 3rd century BCE, the idea of a spherical Earth began to become articulated as a scientific matter. During the same period, the development of a geological view of the Earth also began to emerge, with philosophers understanding that it consisted of minerals, metals, and that it was subject to a very slow process of change.

However, it was not until the 16th and 17th centuries that a scientific understanding of planet Earth and its structure truly began to advance. In 1692, Edmond Halley (discoverer of Halley’s Comet) proposed what is now known as the “Hollow-Earth” theory. In a paper submitted to Philosophical Transactions of Royal Society of London, he put forth the idea of Earth consisting of a hollow shell about 800 km thick (~500 miles).

Between this and an inner sphere, he reasoned there was an air gap of the same distance. To avoid collision, he claimed that the inner sphere was held in place by the force of gravity. The model included two inner concentric shells around an innermost core, corresponding to the diameters of the planets Mercury, Venus, and Mars respectively.

Halley’s construct was a method of accounting for the values of the relative density of Earth and the Moon that had been given by Sir Isaac Newton, in his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687) – which were later shown to be inaccurate. However, his work was instrumental to the development of geography and theories about the interior of the Earth during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Another important factor was the debate during the 17th and 18th centuries about the authenticity of the Bible and the Deluge myth. This propelled scientists and theologians to debate the true age of the Earth, and compelled the search for evidence that the Great Flood had in fact happened. Combined with fossil evidence, which was found within the layers of the Earth, a systematic basis for identifying and dating the Earth’s strata began to emerge.

The development of modern mining techniques and growing attention to the importance of minerals and their natural distribution also helped to spur the development of modern geology. In 1774, German geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner published Von den äusserlichen Kennzeichen der Fossilien (On the External Characters of Minerals) which presented a detailed system for identifying specific minerals based on external characteristics.

In 1741, the National Museum of Natural History in France created the first teaching position designated specifically for geology. This was an important step in further promoting knowledge of geology as a science and in recognizing the value of widely disseminating such knowledge. And by 1751, with the publication of the Encyclopédie by Denis Diderot, the term “geology” became an accepted term.

By the 1770s, chemistry was starting to play a pivotal role in the theoretical foundation of geology, and theories began to emerge about how the Earth’s layers were formed. One popular idea had it that liquid inundation, like the Biblical Deluge, was responsible for creating all the geological strata. Those who accepted this theory became known popularly as the Diluvianists or Neptunists.

Another thesis slowly gained currency from the 1780s forward, which stated that instead of water, strata had been formed through heat (or fire). Those who followed this theory during the early 19th century referred to this view as Plutonism, which held that the Earth formed gradually through the solidification of molten masses at a slow rate. These theories together led to the conclusion that the Earth was immeasurably older than suggested by the Bible.

In the early 19th century, the mining industry and Industrial Revolution stimulated the rapid development of the concept of the stratigraphic column – that rock formations were arranged according to their order of formation in time. Concurrently, geologists and natural scientists began to understand that the age of fossils could be determined geologically (i.e. that the deeper the layer they were found in was from the surface, the older they were).

During the imperial period of the 19th century, European scientists also had the opportunity to conduct research in distant lands. One such individual was Charles Darwin, who had been recruited by Captain FitzRoy of the HMS Beagle to study the coastal land of South America and give geological advice.

Darwin’s discovery of giant fossils during the voyage helped to establish his reputation as a geologist, and his theorizing about the causes of their extinction led to his theory of evolution by natural selection, published in On the Origin of Species in 1859.

During the 19th century, the governments of several countries including Canada, Australia, Great Britain and the United States began funding geological surveys that would produce geological maps of vast areas of the countries. Thought largely motivated by territorial ambitions and resource exploitation, they did benefit the study of geology.

By this time, the scientific consensus established the age of the Earth in terms of millions of years, and the increase in funding and the development of improved methods and technology helped geology to move farther away from dogmatic notions of the Earth’s age and structure.

By the early 20th century, the development of radiometric dating (which is used to determine the age of minerals and rocks), provided the necessary the data to begin getting a sense of the Earth’s true age. By the turn of the century, geologists now believed the Earth to be 2 billion years old, which opened doors for theories of continental movement during this vast amount of time.

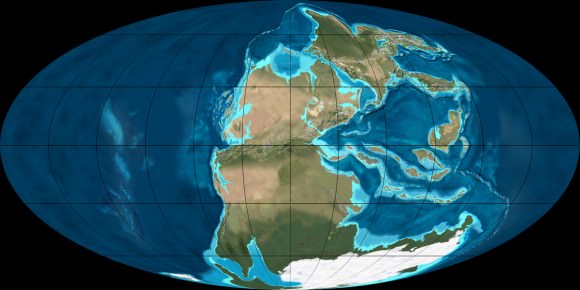

In 1912, Alfred Wegener proposed the theory of Continental Drift, which suggested that the continents were joined together at a certain time in the past and formed a single landmass known as Pangaea. In accordance with this theory, the shapes of continents and matching coastline geology between some continents indicated they were once attached together.

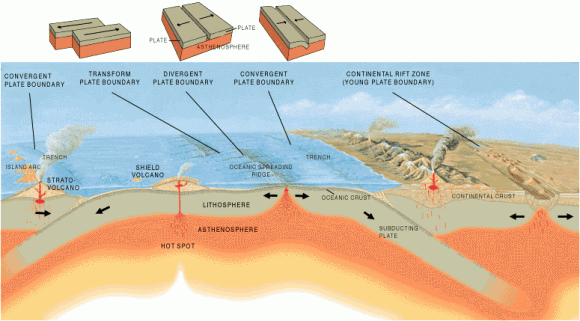

Research into the ocean floor also led directly to the theory of Plate Tectonics, which provided the mechanism for Continental Drift. Geophysical evidence suggested lateral motion of continents and that oceanic crust is younger than continental crust. This geophysical evidence also spurred the hypothesis of paleomagnetism, the record of the orientation of the Earth’s magnetic field recorded in magnetic minerals.

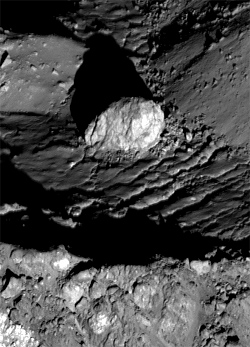

Then there was the development of seismology, the study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other planet-like bodies, in the early 20th century. By measuring the time of travel of refracted and reflected seismic waves, scientists were able to gradually infer how the Earth was layered and what lay deeper at its core.

For example, in 1910, Harry Fielding Ried put forward the “elastic rebound theory”, based on his studies of the 1906 San Fransisco earthquake. This theory, which stated that earthquakes occur when accumulated energy is released along a fault line, was the first scientific explanation for why earthquakes happen, and remains the foundation for modern tectonic studies.

Then in 1926, English scientist Harold Jeffreys claimed that below the crust, the core of the Earth is liquid, based on his study of earthquake waves. And then in 1937, Danish seismologist Inge Lehmann went a step further and determined that within the earth’s liquid outer core, there is a solid inner core.

By the latter half of the 20th century, scientists developed a comprehensive theory of the Earth’s structure and dynamics had formed. As the century played out, perspectives shifted to a more integrative approach, where geology and Earth sciences began to include the study of the Earth’s internal structure, atmosphere, biosphere and hydrosphere into one.

This was assisted by the development of space flight, which allowed for Earth’s atmosphere to be studied in detail, as well as photographs taken of Earth from space. In 1972, the Landsat Program, a series of satellite missions jointly managed by NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey, began supplying satellite images that provided geologically detailed maps, and have been used to predict natural disasters and plate shifts.

Earth’s Layers:

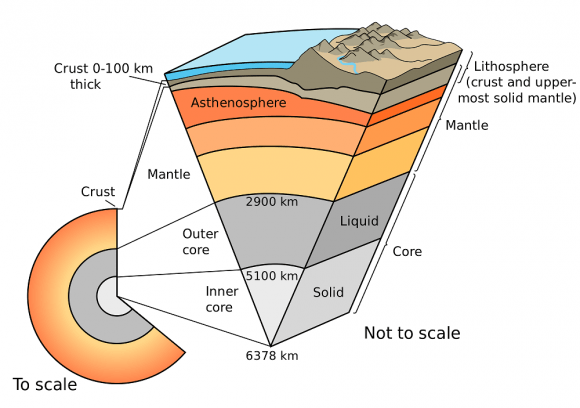

The Earth can be divided into one of two ways – mechanically or chemically. Mechanically – or rheologically, meaning the study of liquid states – it can be divided into the lithosphere, asthenosphere, mesospheric mantle, outer core, and the inner core. But chemically, which is the more popular of the two, it can be divided into the crust, the mantle (which can be subdivided into the upper and lower mantle), and the core – which can also be subdivided into the outer core, and inner core.

The inner core is solid, the outer core is liquid, and the mantle is solid/plastic. This is due to the relative melting points of the different layers (nickel–iron core, silicate crust and mantle) and the increase in temperature and pressure as depth increases. At the surface, the nickel-iron alloys and silicates are cool enough to be solid. In the upper mantle, the silicates are generally solid but localized regions of melt exist, leading to limited viscosity.

In contrast, the lower mantle is under tremendous pressure and therefore has a lower viscosity than the upper mantle. The metallic nickel–iron outer core is liquid because of the high temperature. However, the intense pressure, which increases towards the inner core, dramatically changes the melting point of the nickel–iron, making it solid.

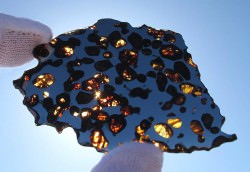

The differentiation between these layers is due to processes that took place during the early stages of Earth’s formation (ca. 4.5 billion years ago). At this time, melting would have caused denser substances to sink toward the center while less-dense materials would have migrated to the crust. The core is thus believed to largely be composed of iron, along with nickel and some lighter elements, whereas less dense elements migrated to the surface along with silicate rock.

Earth’s Crust:

The crust is the outermost layer of the planet, the cooled and hardened part of the Earth that ranges in depth from approximately 5-70 km (~3-44 miles). This layer makes up only 1% of the entire volume of the Earth, though it makes up the entire surface (the continents and the ocean floor).

The thinner parts are the oceanic crust, which underlies the ocean basins at a depth of 5-10 km (~3-6 miles), while the thicker crust is the continental crust. Whereas the oceanic crust is composed of dense material such as iron magnesium silicate igneous rocks (like basalt), the continental crust is less dense and composed of sodium potassium aluminum silicate rocks, like granite.

The uppermost section of the mantle (see below), together with the crust, constitutes the lithosphere – an irregular layer with a maximum thickness of perhaps 200 km (120 mi). Many rocks now making up Earth’s crust formed less than 100 million (1×108) years ago. However, the oldest known mineral grains are 4.4 billion (4.4×109) years old, indicating that Earth has had a solid crust for at least that long.

Upper Mantle:

The mantle, which makes up about 84% of Earth’s volume, is predominantly solid, but behaves as a very viscous fluid in geological time. The upper mantle, which starts at the “Mohorovicic Discontinuity” (aka. the “Moho” – the base of the crust) extends from a depth of 7 to 35 km (4.3 to 21.7 mi) downwards to a depth of 410 km (250 mi). The uppermost mantle and the overlying crust form the lithosphere, which is relatively rigid at the top but becomes noticeably more plastic beneath.

Compared to other strata, much is known about the upper mantle, thanks to seismic studies and direct investigations using mineralogical and geological surveys. Movement in the mantle (i.e. convection) is expressed at the surface through the motions of tectonic plates. Driven by heat from deeper in the interior, this process is responsible for Continental Drift, earthquakes, the formation of mountain chains, and a number of other geological processes.

![Computer simulation of the Earth's field in a period of normal polarity between reversals.[1] The lines represent magnetic field lines, blue when the field points towards the center and yellow when away. The rotation axis of the Earth is centered and vertical. The dense clusters of lines are within the Earth's core](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Geodynamo_Between_Reversals-e1449100829326-580x442.gif)

The crystallized melt products near the surface, upon which we live, are typically known to have a lower magnesium to iron ratio and a higher proportion of silicon and aluminum. These changes in mineralogy may influence mantle convection, as they result in density changes and as they may absorb or release latent heat as well.

In the upper mantle, temperatures range between 500 to 900 °C (932 to 1,652 °F). Between the upper and lower mantle, there is also what is known as the transition zone, which ranges in depth from 410-660 km (250-410 miles).

Lower Mantle:

The lower mantle lies between 660-2,891 km (410-1,796 miles) in depth. Temperatures in this region of the planet can reach over 4,000 °C (7,230 °F) at the boundary with the core, vastly exceeding the melting points of mantle rocks. However, due to the enormous pressure exerted on the mantle, viscosity and melting are very limited compared to the upper mantle. Very little is known about the lower mantle apart from that it appears to be relatively seismically homogeneous.

Outer Core:

The outer core, which has been confirmed to be liquid (based on seismic investigations), is 2300 km thick, extending to a radius of ~3,400 km. In this region, the density is estimated to be much higher than the mantle or crust, ranging between 9,900 and 12,200 kg/m3. The outer core is believed to be composed of 80% iron, along with nickel and some other lighter elements.

Denser elements, like lead and uranium, are either too rare to be significant or tend to bind to lighter elements and thus remain in the crust. The outer core is not under enough pressure to be solid, so it is liquid even though it has a composition similar to that of the inner core. The temperature of the outer core ranges from 4,300 K (4,030 °C; 7,280 °F) in the outer regions to 6,000 K (5,730 °C; 10,340 °F) closest to the inner core.

Because of its high temperature, the outer core exists in a low viscosity fluid-state that undergoes turbulent convection and rotates faster than the rest of the planet. This causes eddy currents to form in the fluid core, which in turn creates a dynamo effect that is believed to influence Earth’s magnetic field. The average magnetic field strength in Earth’s outer core is estimated to be 25 Gauss (2.5 mT), which is 50 times the strength of the magnetic field measured on Earth’s surface.

Inner Core:

Like the outer core, the inner core is composed primarily of iron and nickel and has a radius of ~1,220 km. Density in the core ranges between 12,600-13,000 kg/m³, which suggests that there must also be a great deal of heavy elements there as well – such as gold, platinum, palladium, silver and tungsten.

The temperature of the inner core is estimated to be about 5,700 K (~5,400 °C; 9,800 °F). The only reason why iron and other heavy metals can be solid at such high temperatures is because their melting temperatures dramatically increase at the pressures present there, which ranges from about 330 to 360 gigapascals.

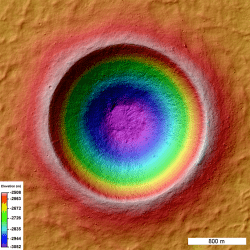

Because the inner core is not rigidly connected to the Earth’s solid mantle, the possibility that it rotates slightly faster or slower than the rest of Earth has long been considered. By observing changes in seismic waves as they passed through the core over the course of many decades, scientists estimate that the inner core rotates at a rate of one degree faster than the surface. More recent geophysical estimates place the rate of rotation between 0.3 to 0.5 degrees per year relative to the surface.

Recent discoveries also suggest that the solid inner core itself is composed of layers, separated by a transition zone about 250 to 400 km thick. This new view of the inner core, which contains an inner-inner core, posits that the innermost layer of the core measures 1,180 km (733 miles) in diameter, making it less than half the size of the inner core. It has been further speculated that while the core is composed of iron, it may be in a different crystalline structure that the rest of the inner core.

What’s more, recent studies have led geologists to conjecture that the dynamics of deep interior is driving the Earth’s inner core to expand at the rate of about 1 millimeter a year. This occurs mostly because the inner core cannot dissolve the same amount of light elements as the outer core.

The freezing of liquid iron into crystalline form at the inner core boundary produces residual liquid that contains more light elements than the overlying liquid. This in turn is believed to cause the liquid elements to become buoyant, helping to drive convection in the outer core. This growth is therefore likely to play an important role in the generation of Earth’s magnetic field by dynamo action in the liquid outer core. It also means that the Earth’s inner core, and the processes that drive it, are far more complex than previously thought!

Yes indeed, the Earth is a strange and mysteries place, titanic in scale as well as the amount of heat and energy that went into making it many billions of years ago. And like all bodies in our universe, the Earth is not a finished product, but a dynamic entity that is subject to constant change. And what we know about our world is still subject to theory and guesswork, given that we can’t examine its interior up close.

As the Earth’s tectonic plates continue to drift and collide, its interior continues to undergo convection, and its core continues to grow, who knows what it will look like eons from now? After all, the Earth was here long before we were, and will likely continue to be long after we are gone.

We have written many articles about Earth for Universe Today. Here’s are some Interesting Facts about Earth, and here’s one about the Earth’s inner inner core, and another about how minerals stop transferring heat at the core.

Want more resources on the Earth? Here’s a link to NASA’s Human Spaceflight page, and here’s NASA’s Visible Earth.

If you’d like more info on Earth, check out NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide on Earth. And here’s a link to NASA’s Earth Observatory.

We’ve also recorded an episode of Astronomy Cast all about Earth. Listen here, Episode 51: Earth.